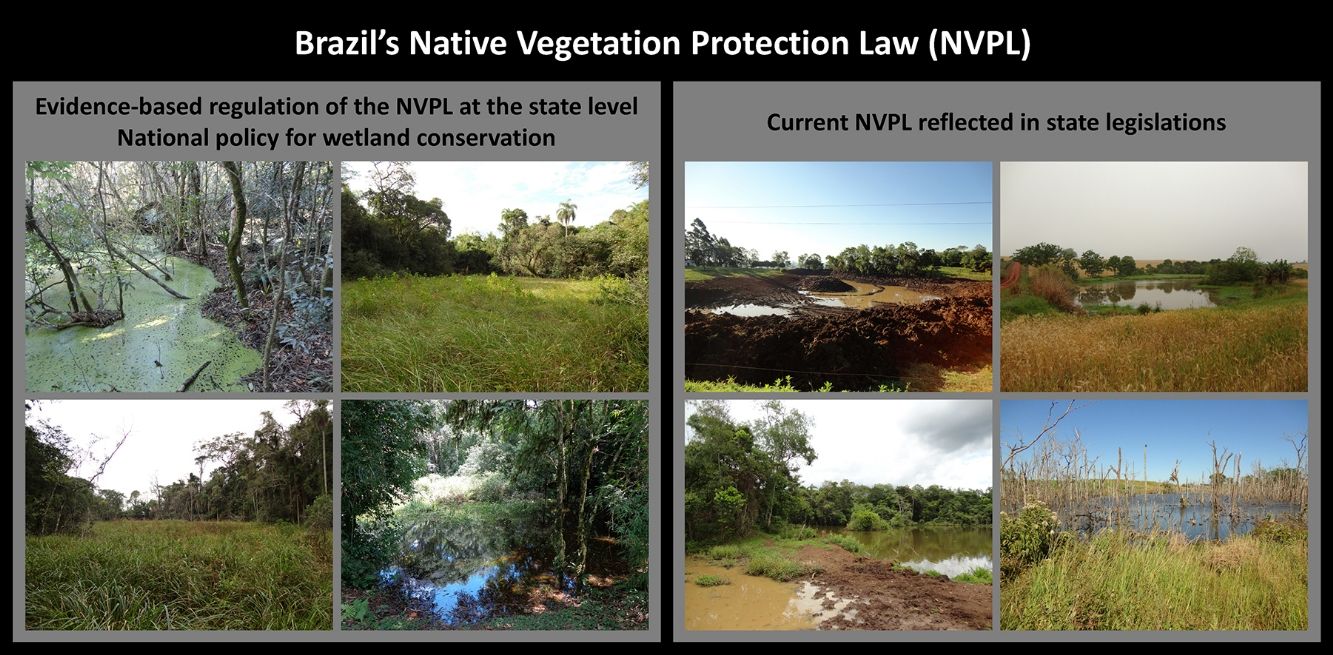

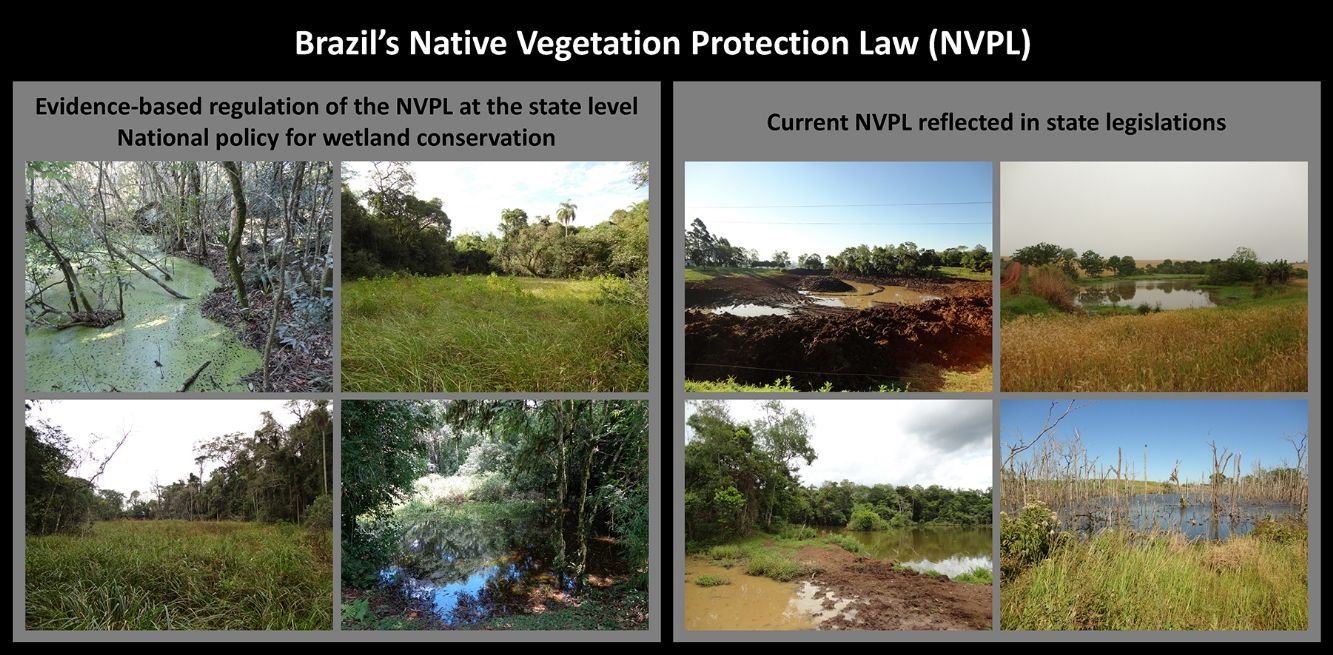

Pond systems perform a myriad of ecosystem services and make unique contributions to aquatic biodiversity conservation at the landscape scale. Despite their high conservation value, in Brazil, natural ponds have been lost and degraded at alarming rates. The remaining have become exceptionally vulnerable after the enactment of the recent Native Vegetation Protection Law (NVPL), whose unsustainable policies threatens to collapse these ecosystems. Although in force since 2012, the regulation of the NVPL is still in course at the state level, offering a unique opportunity to reduce the gap between science and policy. Here, we show why the NVPL threatens ponds and how its inadequacies can be overcome. Finally, we emphasize the need to create a national policy specifically focusing on wetland conservation.

Ponds – temporary or permanent upland-embedded wetlands (UEWs; sensu Calhoun et al., 2017a) with ≤2ha (Biggs et al., 2005; Hamerlík et al., 2014) – are important landscape features, performing a portfolio of hydrological, biogeochemical, and biological functions crucial to maintaining the ecological integrity of watersheds and the provision of ecosystem services (Cohen et al., 2016; Evenson et al., 2018). Benefits provided by pond systems include carbon sequestration (Craft et al., 2017), material transformation (Marton et al., 2015), water quality improvement (Hansen et al., 2018), hydrologic regulation (Rains et al., 2016), and biodiversity support (Schofield et al., 2018). Particularly noteworthy are the contributions of ponds to the protection and management of the aquatic biota at the regional scale. Compared with lakes, rivers, streams, and ditches, ponds present the highest gamma diversity and support a disproportionately larger number of unique and rare species, in addition to having the smallest average catchment size, what makes them to be amongst the most valuable, easiest, and cheapest waterbody types to conserve (Davies et al., 2008a,b).

Despite their high conservation value, ponds have been historically neglected in Brazil, leading to the alteration or destruction of their majority in anthropized landscapes, caused mainly by agricultural expansion, urban development, combating mosquito-borne diseases, and road constructions (e.g., Macedo-Soares et al., 2010; Moraes et al., 2014; Setubal et al., 2016, personal observations). Although there are no estimates of the former and current distribution, number, and size of UEWs for any region of the Brazilian territory, a recent paper reported that 89% of wetland area in South America was lost after 1900 (Creed et al., 2017), which may mean that Brazil is inserted in the region with the highest conversion rate of ponds in the world.

Regardless of their conservation status, all the remaining ponds outside conservation units become exceptionally vulnerable after the enactment of the recent Native Vegetation Protection Law (NVPL; Law n° 12,651 from May 25, 2012; http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/l12651.htm), which replaced the 1965 “Forest Code”. The NVPL is the primary environmental legislation on private land, regulating, in the case of UEWs, the conservation and restoration of “buffer zones” (legally considered Permanent Preservation Areas – PPAs) in their surroundings. In practical terms, however, the NVPL does not present clear elements that ensure the protection of ponds, besides establishing a series of unsustainable policies that put their ecosystem functions and structure at risk.

Although in force since 2012, the regulation of the NVPL at the state level is still in course, offering a unique opportunity to reduce the gap between science and policy. In this context, we have expanded the debate around the NVPL (e.g., Brancalion et al., 2016) and pointed out potential solutions to overcome the inadequacies that threaten to extirpate the natural ponds in the most biodiverse country of the planet (Brandon et al., 2005).

Inadequacies of the NVPLOne of the main inadequacies of the NVPL, which turns all ponds vulnerable, is the dissociation of the indissociable, i.e., the untying of the concept of “wetlands” from the term “ponds” (not conceptualized in the law). As the NVPL does not directly protect wetlands (the term is not used in any public policy) through PPAs, but supposedly contemplates ponds (which are wetlands), what should be considered a pond is unclear, making conservation strategies impractical.

Equally comprehensive and potentially catastrophic threats stem from the fact that the NVPL does not provide protection for ponds with <1ha and does not mention UEWs that hold surface water or near-surface groundwater temporarily. This means that virtually all ponds are at risk, once the large majority generally have less than one hectare (e.g., ca. 76% and 99%; Martin et al., 2012 and Williams et al., 2010, respectively) and, depending on the climatic characteristics in certain regions (e.g., in the semi-arid Northeast Brazil), the totality can be temporary (Junk et al., 2014; Lane and D’Amico, 2016). The imminent massive conversion of small and temporary ponds, in addition to causing direct losses of biodiversity and of a myriad of essential and unique ecosystem services (Calhoun et al., 2017b; Cohen et al., 2016), will also dramatically reduce the connectivity between the few large (≥1ha) and permanent ponds that may remain and, consequently, compromise the viability of metapopulations (Gibbs, 2000) and metacommunities (Dias et al., 2016). In the short to medium term, the inadequacies herein mentioned can mean the extirpation of almost the totality of natural ponds outside conservation units in Brazil, given that just a tiny fraction of the original number of these ecosystems currently remains. In the long term, however, all ponds can be lost, once the successional process tends to transform permanent ponds in temporary ones (Biggs et al., 1994), without legal protection.

The NVPL also undermines pond conservation through the requirement of extremely narrow PPAs. In urban and rural areas, the width of the PPAs that must be maintained is 30m and 50m, respectively. However, landowners that suppressed PPAs before July 22, 2008, must restore them up to the width of only 5m, 8m, 15m and 30m on properties with up to 1, >1–2, >2–4 and >4 fiscal modules, respectively (for details about fiscal modules, see Brancalion et al., 2016). Considering that the area of ponds and of their catchments are positively correlated, and that the PPAs width is not proportionally adjustable to pond size, it is expected that most of the uplands in depressional watersheds will remain economically exploited or humanly inhabited (especially those around large ponds on small properties in irregular situation), which has been shown to deteriorate pond environmental properties (Novikmec et al., 2016) and reduce their conservation value (Stuber et al., 2016; Thornhill et al., 2017). Additionally, insufficient buffer zones can accelerate pond clogging, increasing the likelihood of invasions by exotic species (Tsai et al., 2012), causing the loss of ecosystem services (e.g., water storage capacity) and, ultimately, the disappearance of these wetlands from the landscapes (Bowen and Johnson, 2017). It is also important to mention that probably all the PPAs proposed in the NVPL cannot be considered buffer zones per se, but only part of the full range of terrestrial habitats essential for various semiaquatic species to complete their life cycles (Semlitsch and Bodie, 2003).

How PPAs can be restored in family farms is also a cause of great concern. Among the strategies foreseen in the NVPL, landowners can use exotic woody species in the restoration of 50% of the PPAs, even in grassy biomes, where afforestation can devastate ecosystem functions (Veldman et al., 2015). Exotic woody species within depressional watersheds can alter a range of pond environmental features, reducing species richness and abundance, and modifying community composition (Stenert et al., 2012). The consequences of this inadequacy, however, can be much more severe. In the Argentine Pampas, e.g., an Eucalyptus camaldulensis stand reduced groundwater to levels (>50cm) (Engel et al., 2005) higher than the mean depth of temporary ponds (e.g., 26cm) and close to the mean depth of permanent ones (e.g., 65cm) (Hill et al., 2017). Changes of this magnitude in the groundwater table can dry temporary ponds and transform permanent ponds in temporary ones (unprotected by NVPL), determining the loss or collapse of biodiversity and ecosystem services, once hydrology is the core control of aquatic ecosystem functions (McLaughlin and Cohen, 2013). PPAs with exotic woody species, therefore, assume a contradictory role to their finality of safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems’ services and structure.

Another inadequacy in environmental terms is the authorization of aquaculture in converted PPAs on rural properties with ≤15 fiscal modules. However, although the NVPL refers only to PPAs, it does not provide explicit impediments to aquaculture (and any other practice) within ponds that are not legally protected, substantially expanding the possible multiplicity of environmental (reviewed by Martinez-Porchas and Martinez-Cordova, 2012) and biological (reviewed by De Silva, 2012) impacts resulting from such activities. The use of natural ponds for aquaculture, like conventional and organic rice cultivation (which includes the application of pesticides and fertilizers and/or intensive mechanization and water management), was shown to reduce species abundance and biomass and alter the communities functional and taxonomic diversity and composition (Dalzochio et al., 2016a,b; Linke et al., 2014). Moreover, aquaculture can compromise the provision of several pond services, like the water quality improvement (Hansen et al., 2018), through the discharge of polluted effluents (Rosa et al., 2013), and the hydrologic regulation (Rains et al., 2016), through water management (Dalzochio et al., 2016a). Aquaculture within PPAs, in turn, in addition to intensifying land use within depressional watersheds and maintaining portions of PPAs without native vegetation, whose negative impacts were mentioned previously, may have similar impacts on pond functions, mainly because of the temporary or permanent release of effluents into the ponds, either by surface (e.g., by the frequent practice of draining cultivated wetlands; Linke et al., 2014) or ground-water flows.

Lastly, the NVPL also threatens pond functions for not protecting swales and ephemeral streams that temporarily or permanently connect ponds to downgradient waterbodies/wetlands through surface water flows (see Fig. 2a and b in Lane et al., 2018). Since ecosystem functions emerge from multiple connections, the predictable degradation or loss of swales and ephemeral streams are expected to severely impair biodiversity and ecosystem services supported by ponds (Lane et al., 2018; Schofield et al., 2018).

Solutions to the inadequacies of the NVPLWe identified the following potential solutions to the inadequacies of the NVPL: (1) to adopt a clear and comprehensive definition of ponds; (2) to provide protection to the entire continuum of wetland connectivity (Cohen et al., 2016); (3) to require PPAs with at least 50m width around ponds to maximize the retention of contaminants and sediments (Haukos et al., 2016) until more studies introduce biological criteria for the design of buffer zones (e.g., Semlitsch and Bodie, 2003); (4) to consider only the use of native species for the active restoration of PPAs; and (5) to explicitly prohibit the use of ponds and PPAs for the practice of aquaculture.

Final remarksThe regulation of the NVPL at the state level, currently underway, offers probably the best opportunity to supplant its inadequacies, since states can adopt more rigorous, but never more permissive, conservation measures than the federal law. Our suggestions, however, should be interpreted only as emergency strategies in an attempt to avoid the imminent collapse of pond functions in Brazil. Effective conservation initiatives, which will need to address the projected impacts of climate change (Junk et al., 2013) and the alarming rate of pond loss and degradation, will trigger a demand for actions that will make the Brazilian environmental legislation mostly obsolete. Therefore, we emphatically reinforce the need to create a national policy specifically focusing on wetland conservation (Junk et al., 2014), which should include the protection, restoration, management, mapping, monitoring and, especially, the creation (e.g., https://freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/million-ponds/) of ponds. Dialogue between scientists and policymakers will be essential in this process (Azevedo-Santos et al., 2017; Karam-Gemael et al., 2017).

Declarations of interestNone.

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. DG was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES); RPM, RLB and SMT received grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq); RLB was also supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).