Rhodoliths are free-living nodules formed by crustose coralline algae that promote multi-dimensional microhabitats for a highly diverse community. Because their CaCO3 production, rhodolith beds constitute areas of interest for mining activities. On the other hand, other goods and services provided by these environments such as nurseries habitats, fishing and climate regulation remain undersized. Besides directly CaCO3 exploitation, these diverse ecosystems within the Brazilian economic exclusive zone are often covering potentially sites for oil and gas extraction. The IBAMA (Environmental Agency of the Brazilian government) have been applying the precautionary principle to deny requests for oil/gas drilling activities where rhodolith beds occur. Here, we discuss recent data about diversity associated with rhodoliths and also record the “rare” worm Nuchalosyllis cf. maiteae. More than the distribution of one only species, our finding is an emblematic example of our infancy knowledge state about diversity associated with rhodolith beds in southwestern Atlantic. We argue that these knowledge is still insufficient to subside any attempt in classify priorities areas for oil wells drilling. In addition, we claim that the precautionary principle adopted by IBAMA must prevalence until we have robust data allowing predictions concerning higher or lower biodiversity associated with rhodolith beds.

Rhodoliths are free-living calcareous nodules built mainly by crustose coralline algae. They occur worldwide and may form large beds that cover huge expanse of tropical, temperate, and even polar shelves, providing multi-dimensional hard microhabitats for diverse biological communities (Foster et al., 2013). Because of their huge CaCO3 accumulation, rhodolith beds constitute areas of great interest for carbonates’ mining that supplies agricultural and industrial applications (Amado-Filho et al., 2012a; Moura et al., 2013). While rhodolith beds are largely and mistakenly seen as mineral resources, the ecosystem services they provide, such as fishing and climate regulation, are grossly underrated in environmental impact assessments (Amado-Filho and Pereira-Filho, 2012). In Brazil, the country with the world's largest rhodolith beds, extraction of up to 18t/companyyear−1 may be regularly licensed by IBAMA, the Federal Environmental Licensing Agency (Instrução Normativa 89, Feb. 02, 2006). Although sub-surface rhodoliths are often alive and definitely harbor high marine biodiversity, the Brazilian law refers to them as non-living marine resources, with exploratory regulations established by the National Mining Department (Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral – DNPDM). Moreover, rhodolith beds overlap with several oil and gas fields within the Brazilian Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The building of new infrastructure in such areas has been recently restricted by IBAMA, based on the Precautionary Principle – a fundamental tool for countering the chronic overlook of scientific uncertainties in an unscientific manner (Cooney, 2004). Despite recent progress (e.g., Riul et al., 2009; Amado-Filho et al., 2010; Bahia et al., 2010; Brasileiro et al., 2015), knowledge about the distribution and biodiversity associated with rhodolith beds in Brazil is still fragmented and incomplete, impeding thorough environmental impact assessments of the steadily growing industrial activities. Paradoxically, uncertainties in predicting environmental impacts have been evoqued by economic groups as a reason for the approval of mining licenses (Cooney, 2004). Once rhodolith beds cover extensive areas of the Brazilian EEZ (Fig. 1A), large-scale mining and hydrocarbon's exploitation are indeed an imminent threat with yet unpredictable consequences. Here, while recording the occurrence of the “rare genus” Nuchalosyllis (Polychaeta) in the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (FNA), we emphasize the major knowledge gaps about the biodiversity associated to Brazilian rhodolith beds, and the consequences for environmental licensing.

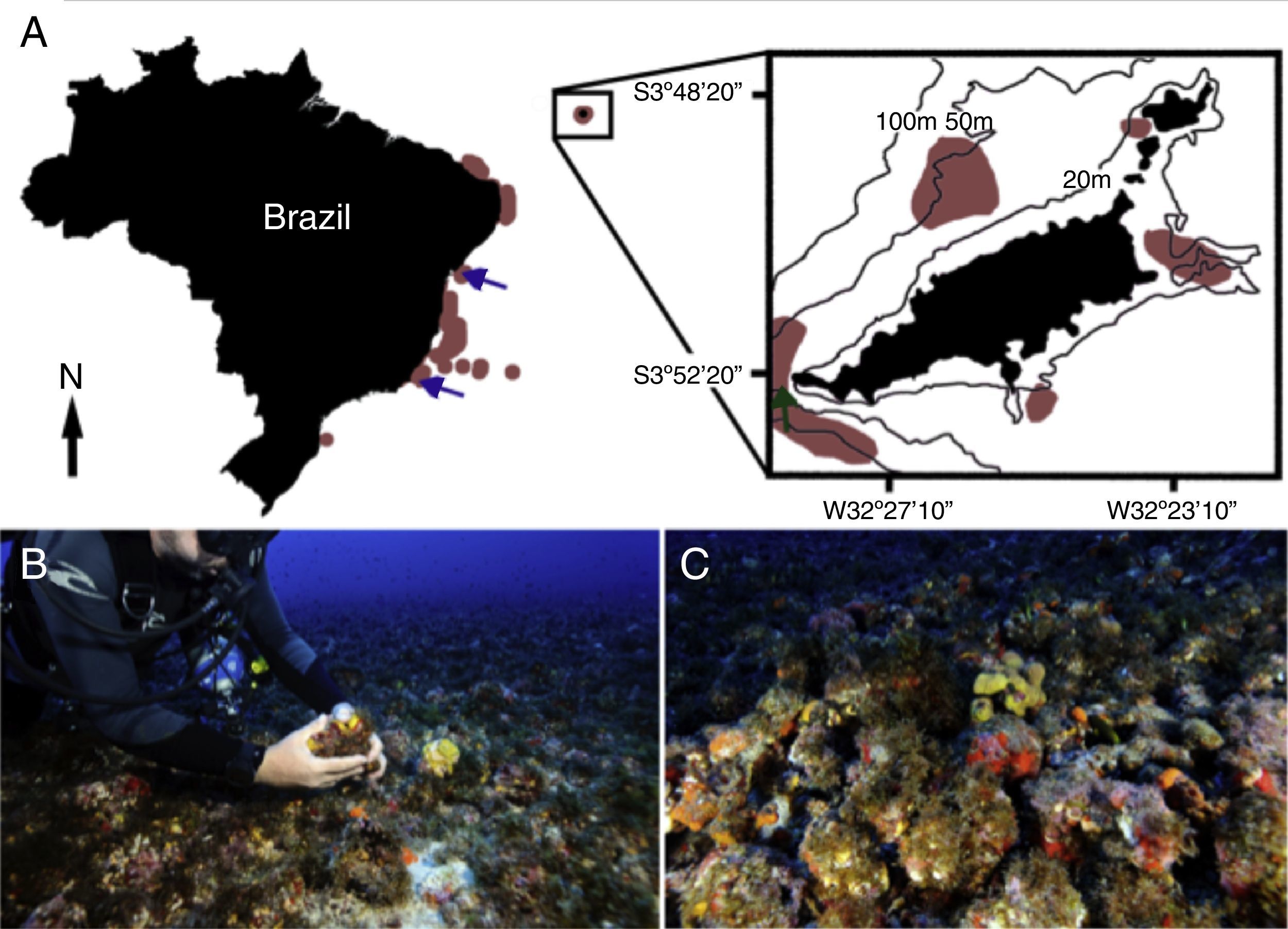

Sampling localities for all known specimens of Nuchalosyllis. (A) Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (detail). Light brown patches indicate areas where rhodolith beds have been mapped (Gherardi, 2004; Pascelli et al., 2013; Amado-Filho et al., 2007; Amado-Filho et al., 2010; Villas-Boas et al., 2013; Pereira-Filho et al., 2012; Amado-Filho et al., 2012a; Bahia et al., 2010; Riul et al., 2009; Testa and Bosence, 1999; Amado-Filho et al., 2012b, respectively from south to north). Blue arrows indicate localities of the two known Nuchalosyllis species, (Fukuda and Nogueira, 2012; Rullier and Amoureux, 1979). Dark green arrow indicates the site where we sampled Nuchalosyllis at 40m depth. (B and C) Detail of rhodolith bed (Photos: Zaira Matheus).

Before our find (Fig. 1) (specimen deposited in MNRJP785), Nuchalosyllis maiteae was only known for the holotype (MZUSP 01016) collected at 75m depth offshore Rio de Janeiro State (Fukuda and Nogueira, 2012). Such as other known specie of the same genus, N. maiteae was initially obtained by ship-based dredging and grabbing. Despite being the tools used to provide most of the currently available biological data about rhodolith-associated biodiversity (Foster et al., 2013), dredging and grabbing are limited for sampling small invertebrates within rhodoliths’ microhabitats, especially the soft bodied, cryptic and infaunal species that can have significant roles in food web (Foster et al., 2013; Kenchington and Hutchings, 2012). Only recently the use of SCUBA has been recognized and established as a complimentary tool for sampling such soft-bodied infaunal species (Foster et al., 2013). For example, SCUBA-based assessments in California, USA, revealed eight species of cryptofaunal chitons, four of which were previously undescribed (Clark, 2000). Santos et al. (2011) also used SCUBA to sample honeycomb worms (Polychaeta: Sabellariidae), finding that six of the ten Sabellaria species known from Brazil occur associated with rhodolith beds, including a new species that is apparently restricted to rodoliths.

Despite the aforementioned value for comprehensive biodiversity assessments, SCUBA recreational standards limits sampling to <30m depths. Recently, we used mixed-gas (TRIMIX) and technical diving techniques to sample rhodolith beds in scattered continental and oceanic localities along the Brazilian coast (e.g. Pereira-Filho et al., 2012; Moura et al., 2013; Amado-Filho et al., 2016). Although we sampled only one specimen of N. cf. maiteae in the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (i.e.; >2000km from the type and only known locality) (Figs. 1 and 2), it is possible to hypothesized that the distribution of this taxon is much wider than previously known, and that sampling effort is insufficient to any comprehensive understanding about the biodiversity harbored by this habitat. More than an additional range extension record for one of hundreds of thousands “worm” species, N. maiteae is an emblematic example of the incipient knowledge about the biodiversity of Southwestern Atlantic rhodolith beds. Conversely, research and discovery of hydrocarbon exploitation fields rapidly increased in the last decade, especially in the mesophotic habitats of this region (e.g., Moura et al., 2013), many of those in rhodolith beds such as Peregrino oil field, Campos Basin (Tâmega et al., 2013, 2014), the area where N. maiteae was discovered. Offshore drilling increases the concentration of suspended particles (Patin, 1999), with well-established negative effects over the health of crustose coralline algae (e.g., Reynier et al., 2015) and community-wide changes from sedimentation and contamination (Patin, 1999).

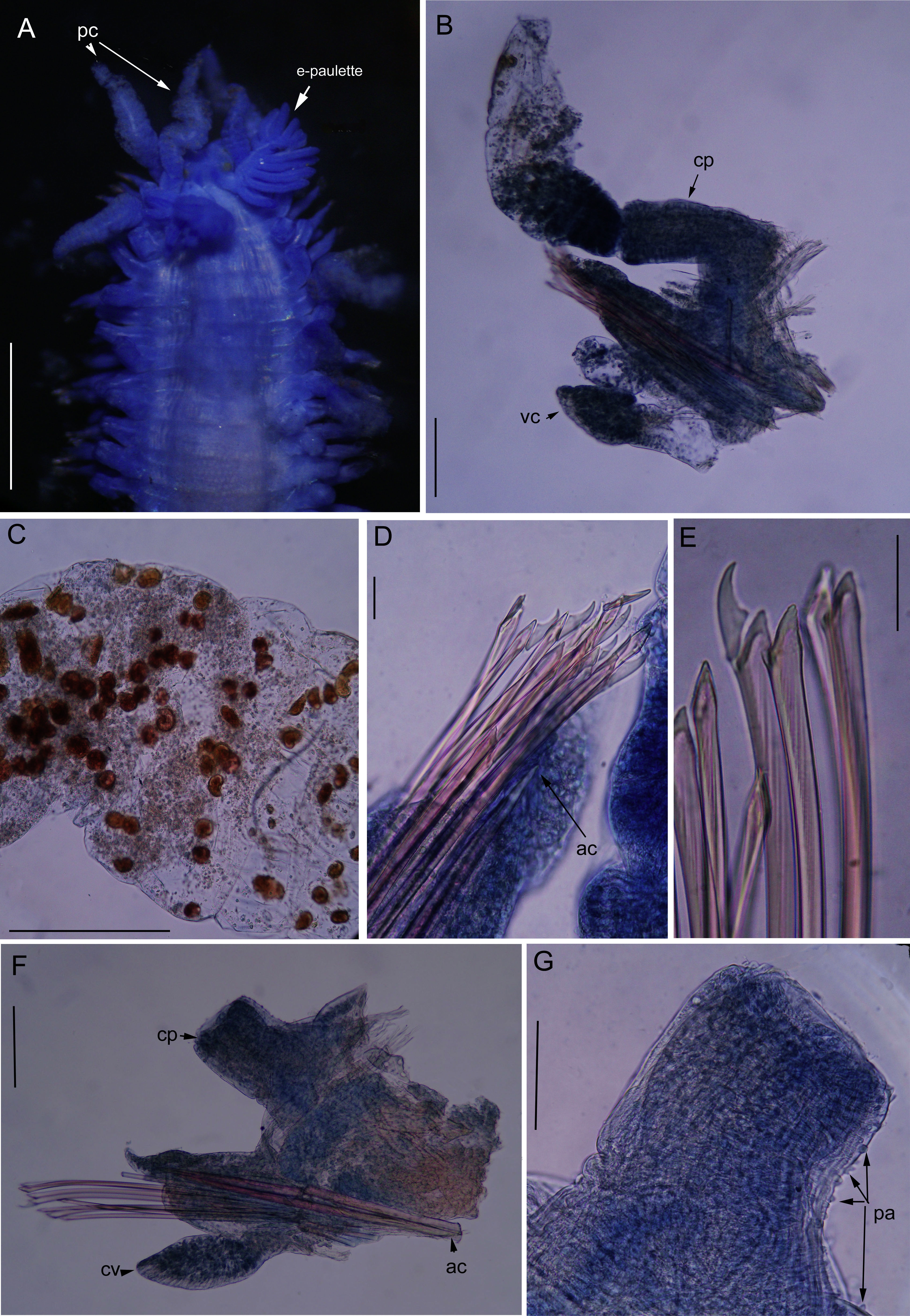

Nuchalosyllis cf. maiteae. (A) Anterior end, dorsal view. (B) Parapodia 15, posterior view; (C) detail of dorsal cirri with dark red inclusions; (D) Chaetae heterogomph falciger from parapodia 15; (E) Chaetae heterogomph falciger from parapodia 41; (F) parapodia 41, posterior view, dorsal cirri lost; (G) dorsal cirrophore with papillae. Papillae. Legends: ac., Acicula; cp., Cirrophore; pa., Papillae; pc., Peristomial cirri; vc., Ventral cirri. Scale: A. 0.8mm; B. 0.13mm; C. 0.25mm; D. 0.03mm; E. 0.03mm; F. 0.1mm; G. 0.08mm.

The term “rare species” is associated to low frequency and small population sizes (Cao et al., 1998). Even only two specimens of N. maiteae have been found up to date; the sampling effort is too limited to classify it or any other associated species as rare or abundant. Basic information about predictor variables of associated biodiversity is still lacking (e.g.; rhodolith size, volume, form, complexity and density). Rhodolith beds are extensive and heterogeneous habitats, and the small spatial scales within the nodules represent and additional challenge for designing comprehensive sampling programs to assess biodiversity patterns. However, considering the increased rates of anthropogenic disturbances (Broderick, 2015), it is clear that the timing needed for extensive sampling is not compatible with the speed at which important management decisions need to be taken (Kenchington and Hutchings, 2012).

While robust data on species’ occurrences and distribution patterns accumulate, and surrogates for biodiversity patterns are developed (Kenchington and Hutchings, 2012), the precautionary principle adopted by IBAMA must be consistently applied in order to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem services provided by rhodolith beds, as evidenced from recent data about macroalgae (Amado-Filho and Pereira-Filho, 2012), fishes (Simon et al., 2016) and the polychaete worm, N. maiteae recorded herein. Instead of pressing IBAMA for rapid licensing, the industries that affect rhodoliths and other megadiversity Brazilian marine ecosystems must, truly, engage in research and conservation initiatives that go beyond the immediate needs of individual exploitation projects.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank the Fernando de Noronha Marine National Park staff for logistic support and research permits (SISBIO/34245-3). Financial support was provided by the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq; grant 484875/2011-6 to GHPF). GMAF, RBFF and RLM acknowledge grants from CNPq, CAPES, FAPERJ and Brasoil. PCV and JBL acknowledge their scholarships from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, processes 2013/26594-4 and 2015/15212-9, respectively).