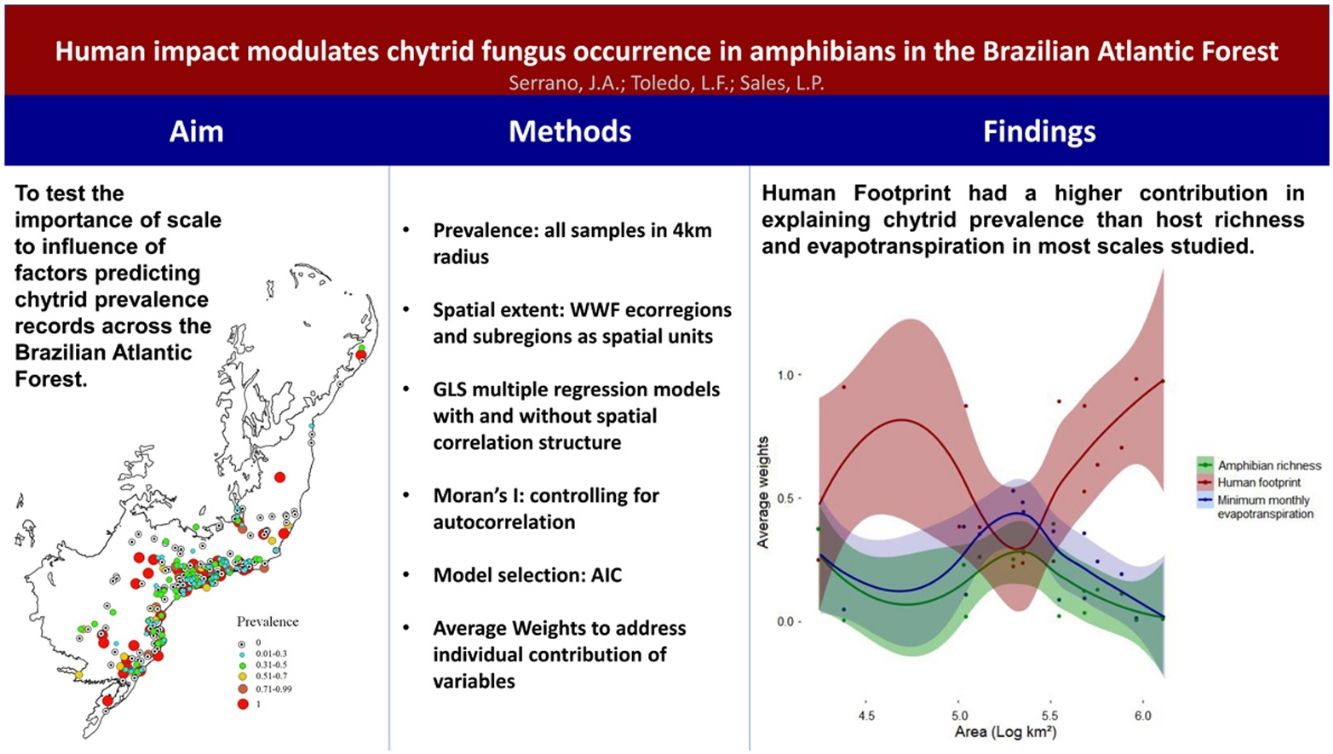

Here, we investigate the influence of scale on different drivers influencing the occurrence of the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. We used gridded values of proxies of the abiotic, biotic and anthropogenic components of landscapes where Bd infects amphibians. Building upon disease prevalence data obtained from a previous work, we fitted GLS multiple regression models using extracted values of the three predictors for each prevalence centroid in space, explicitly controlling for spatial autocorrelation among predictors. To test for the effect of scale on driving the macroecology of Bd infection, we performed tests at different spatial scales. We then used model selection procedures to evaluate the relative contribution of the different predictors on the occurrence of the fungus. The Human Footprint Index better explained a pathogenic species occurrence than largely studied biotic and abiotic factors (i.e., host species distribution and minimum monthly potential evapotranspiration). That effect was, however, not observed at landscape scale, where we found no difference among the relative influence of predictors. Our results indicate that human-mediated impacts on environments can be strong drivers of spread of infectious diseases on native faunas worldwide, thus, suggesting that anthropogenic landscapes may create favourable conditions for the occurrence of this and other infectious diseases.

Infectious wildlife diseases are one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss (Jones et al., 2008). At global scales, infectious diseases have been documented to cause massive declines in populations up to the depletion of native fauna communities (Daszak et al., 2000; Robinson et al., 2010; Woinarski et al., 2011). Climate drives species’ richness distribution, via niche-mediated processes, and ultimately affects the distribution of potential hosts and that of the pathogen itself (Rohr et al., 2011). In this sense, abiotic and biotic components interact synergistically to determine the set of conditions that allow pathogen survival, such as favourable climates and the existence of suitable hosts (Fisher and Garner, 2020). However, human activity also plays an important role in the emergence of infectious diseases by modifying natural environments and creating new opportunities for parasites and pathogens to evolve (Fisher et al., 2012). Diseases may, then, interact with anthropogenic drivers to disturb biological communities and contribute to the species extinctions (Wake and Vredenburg, 2009).

Amphibians are central in this discussion since they comprise the vertebrate group that is with extinction and have been decimated by infectious diseases in the last decades (Wake and Vredenburg, 2009). One specific fungus genus (Batrachochytrium) is particularly related to worldwide amphibian population declines through infection and disease (Scheele et al., 2019). Chytridiomycosis is caused by two congeneric fungal species: Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), described in 1999 (Longcore et al., 1999), and B. salamandrivorans (Bsal), described in 2013 (Martel et al., 2014). The host range of Bsal is mostly restricted to salamanders and newts, with only transient infection in anurans (Stegen et al., 2017), while Bd is a parasitic chytrid fungus that can infect equally anurans, caecilians (Gymnophiona), salamanders and newts (Caudata) (Lambertini et al., 2017; Fisher and Garner, 2020). Spread across the globe, also with the aid of the global trade of amphibians, Bd is now considered one of the greatest threats to native amphibian across the globe (Scheele et al., 2019; Fisher and Garner, 2020).

The macroecological drivers of Bd infection on amphibians are still not well-established, but variation in extrinsic (e.g., climate and landscape configuration) and intrinsic (such as species-specific vulnerability as well as host community structure) are known to influence the dynamics of Bd infection within a community (James et al., 2015). Temperature and precipitation, for example, mediate Bd–amphibian dynamics by limiting vital physiological processes, such as pathogen growth and host evaporative water loss (Raffel et al., 2010). Amongst biotic factors, the distribution of Bd is generally related to features within amphibian host communities, such as species richness and trait composition (Ostfeld and Keesing, 2012, but see Becker et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2013; Searle et al., 2011). There are studies that point to a scenario in which that host species richness increases the pathogen’s occurrence, called the “amplification effect” (Becker et al., 2012); while others argue that species richness decreases pathogen’s occurrence, the “dilution effect” (Searle et al., 2011). However, the global trade of amphibians has led to the co-introduction of Bd fungus into pristine native faunas (O’Hanlon et al., 2018; Fisher and Garner, 2020), across gradients of integrity in human-dominated landscapes (Becker et al., 2012; Beyer et al., 2015), allowing new opportunities for Bd infection and evolution (Fisher et al., 2012).

Moreover, the controversy on assessments of the drivers of infectious diseases, including the infection by Bd fungus, may be an artifact of the scale-dependency of patterns and processes (Ricklefs, 1987; Wiens, 1989). That is so because apparent relationships (e.g. the relative importance of predictors and/or the direction of the relationship) may change according to the spatial scale of the study (Cohen et al., 2016; Halliday and Rohr, 2018; McGill, 2010). For example, biodiversity–disease relationships are expected to be stronger at local scales (Halliday and Rohr, 2018), where biotic interactions occur, and should weaken at regional larger scales, where abiotic factors, such as climate, are expected to predominate (Ricklefs, 1987). Therefore, scale-dependency can become a confounding effect on multiple systems, including the assessment of the drivers of pathogen occurrence and biological invasions (Catford et al., 2022).

In this study, we explored the influence of spatial scale on the importance of biotic, abiotic and anthropogenic influences, using proxies of such components Bd occurrence. We hypothesize that 1) biotic factors should have the highest relative importance at local scales, whereas 2) abiotic climatic variables should have the highest relative importance at regional-continental scales, and that 3) anthropogenic influence should be stronger at mid-range scales, because of the expression of land-use change dynamics at landscape spatial scale (Cohen et al. 2016).

MethodsStudy areaThe Atlantic Forest occupies coastal regions of eastern Brazil and reaches its western maximum extent in eastern Paraguay and northeastern Argentina (Thomé et al., 2010). It covers 1.1 million km2, corresponding to 12% of the land surface of Brazil, stretching for more than 3300 km along the eastern Brazilian coast between the latitudes of 6 and 30 °S (Fundação SOS Mata Atlântica and INPE, 2017). Given this large geographic and latitudinal extent, the Atlantic Forest is floristically diverse, comprising regionally distinct forms of rainforest (ombrophilous and semi-deciduous forests), depending mostly on rainfall regimes and altitude (Oliveira-Filho and Fontes, 2000), which ranges from 0 to about 3000 m above sea level (Safford, 1999). The Atlantic Forest is also highly human-modified and has been reduced to around 11.4 to 16 % of its original forest cover (Ribeiro et al., 2009), which highly threatens the biota with habitat loss (Myers et al., 2000).

In the 1970s and 1980s, enigmatic amphibian declines were recorded in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (states of Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo), which were only later attributed to Bd in museum preserved tadpoles (Carvalho et al., 2017). Declines in amphibian populations, as well as a Bd occurrence, were stronger in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (Carvalho et al., 2017), where highest proportion (28% of all records) of Bd-infected amphibians in the Americas was found (James et al., 2015).

Response dataChytrid occurrence datasetWe used the most up-to-date data on Bd distribution in the American continent, taken from James et al. (2015) work on spatial patterns of Bd distribution. In that previous study, James et al. (2015) calculated Bd prevalence centroids in amphibian populations by aggregating Bd–positive (Bd+) and Bd–negative (Bd-) records within a distance of 4 km and computing the percentage of positives from the total sample size. The data used was compiled from 6,071 Bd+ records among 30,382 adult amphibians who had epidermal tissue collected with swabs and analyzed for fungus detection. Here, we focus on the Brazilian Atlantic Forest and select occurrence data only for this region, resulting in 310 prevalence records, which account for any individual specimens that were collected in any sites within a 4 km radius (see Supplementary materials). We defined ‘site’ as a geographically distinct location having specific coordinates and/or locality descriptions. A ‘record’ was a database entry for a single species for a single year, at a particular site. A given site may have a number of records for different species or years, some for which Bd was found, others for which it was not found.

Predictor dataMinimum monthly potential evapotranspirationJames et al. (2015) found that PET_HE_Bio6, or” minimum monthly potential evapotranspiration” (hereafter MMPE) explained > 20% of the variation in Bd data, so we chose this predictor as a proxy of the abiotic environment that has been found to be an important driving the spatial patterns of the disease. MMPE relates to the ability of the atmosphere to remove water through evapotranspiration processes (Trabucco and Zomer, 2018) and was downloaded from the Global Aridity and PET Database, available at the website https://cgiarcsi.community/data/global-aridity-and-pet-database/.

Host species richnessThe number of potential hosts affects the prevalence of several diseases and are referred to as biotic factors (Ostfeld and Keesing, 2012), therefore, we included the richness of amphibian species as a predictor of Bd prevalence. As Bd has been found to occur in different amphibian taxa other than Anura (Boyle et al., 2004; Gower et al., 2013), we calculated richness of potential hosts from amphibian species range data available at the IUCN Red List website (IUCN, 2019). To obtain species richness estimated for each pixel, we overlaid and summed the polygons of species ranges into a grid of 0.0186 degrees of lat/lon of spatial resolution, using the function using function fasterize() of raster R package (Hijmans, 2020; R Core Team, 2014). As a result, a presence-absence matrix was also generated for each species in each pixel.

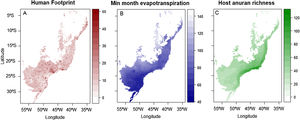

Human Footprint IndexThe expression of wildlife diseases is also affected by human interference (Fisher and Garner, 2020). Indeed, human footprint (HFI) was the second-best predictor of Bd prevalence in the Americas (James et al., 2015). Therefore, we used HFI, compiled by Venter et al. (2016) (Fig. 2A), as a proxy of human interference on landscapes. The HFI dataset is based on information of infrastructure, land cover and human access into natural areas, as a globally standardized metric of the cumulative human footprint on the terrestrial environment at 1 km² resolution from years 1993 to 2009 (Venter et al., 2016). For any grid cell, HFI can range between 0–50.

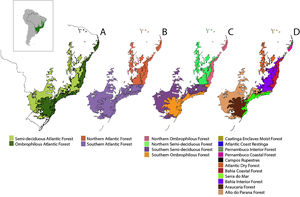

Scale dependency and biogeographic contingenciesTo accommodate the uncertainty related to the spatial scale dependency on the drivers of Bd prevalence, we tested for the influence of a biotic (host richness) and an abiotic factor (MMPE), as well as anthropogenic influences (HFI) at different spatial scales. To do so, we created subdivisions within the Atlantic Forest, using biogeographically relevant areas with the same grain size but different extents to account for differences in spatial scale. We chose to use the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) ecoregions (Olson et al., 2001) within the Atlantic Forest as the smaller study units (Fig. 1). By doing so, we also accommodate processes related to historical and evolutionary contingency that would not have been captured in random subdivisions, since ecoregions encompass similar biological communities and their boundaries roughly coincide with the area over which key ecological processes most strongly interact (Olson et al., 2001).

Different subdivisions and ecoregions of the Atlantic Forest: Ombrophilous and Semi-deciduous Atlantic Forest subregions (A); Northern and Southern Atlantic Forest subregions, delimited by the Doce River (B); Northern and Southern, Ombrophilous and Semi-decidual Atlantic Forest subregions (C); and WWF ecoregions (D).

Since there are other important biogeographic barriers for vertebrate species distributions such as the Doce River (Costa et al., 2000; Pellegrino et al., 2005) and differences in vegetation composition and climate in the semidecidual and ombrophilous portions of the Atlantic Forest (Thomé et al., 2010), we chose to account for those barriers as well, creating large biogeographical regions that comprise our large extent units, which we named subregions of the Atlantic Forest.

As different vegetation structure and moisture are important for amphibian distribution (Thomé et al., 2010) we considered ombrophilous and semideciduous portions of the Atlantic Forest separately (Fig. 1A), as well as northern and southern portions (Fig. 1B) and combinations between these subregions (Fig. 1C). Analyses were performed for the Atlantic Forest as a whole, for its 9 subregions and for the 11 WWF ecoregions that occur in the biome (Fig. 1D).

Data preparation and analysesAll predictors were resampled to the resolution of 0.0186 degrees of lat/long, which roughly corresponds to 11 km2 at the Equator, then clipped and masked to the extent and limits of the Atlantic Forest (Muylaert et al., 2018) using the suit of resample() and mask() functions of raster R package (Hijmans, 2020; R Core Team, 2014).

We verified Spearman correlation between each pair of the predictor variables and found no correlation (r2 < 0.5) between them. We then fitted generalized least square (GLS) multiple regression models (see Cohen et al., 2016) (gls() function, nlme package, R 3.6.1, restricted maximum likelihood fit) (Pinheiro et al., 2019) using extracted values of the three continuous predictors (amphibian richness, HFI and MMPE) for each prevalence centroid in space within our ecoregions, subregions and for the whole Atlantic Forest.

We started the analyses by fitting general models including the three predictors, combining two of the predictors and using each predictor separately for each Atlantic Forest subdivision. We then calculated a spatial variogram (variogram() function, nmle R package) (Pinheiro et al., 2019) and searched for signals of autocorrelation within the graphs for each model. To find the autocorrelation structure best fitted to the global model (considering all predictors), we performed a model selection procedure (described below) comparing the functions exponential, gaussian, spherical, linear rational quadratic (corExp, corGaus, corSpher, corLin, corRatio, nmle package) (Pinheiro et al., 2019). Then performed model selection in order to compare spatially correlated models to non-spatially correlated models. However, for most ecoregions and subregions, spatial correlation was not significant, so we conducted the following steps using models that do not account for spatial autocorrelation.

To test for the effect of spatial scale on each predictor’s relative contribution to the variation on Bd distribution, we conducted a multimodel inference approach. We used multimodel inference (functions model.sel()and model.avg(), from MuMIn R package) (Bartoń, 2019), a procedure that fits models in all possible different combinations of predictors and weights them by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Akaike, 1973). This procedure generates AIC values and Akaike weights for each candidate model. The sum of Akaike weights for all the models in which a predictor variable is present generates the predictor’s average weights, reflecting its relative importance in contributing to the prediction of the response variable (Burnham and Anderson, 2004). To evaluate the relative contribution of the different predictors, we compared the sum of Akaike weights for each predictor, at each spatial scale.

ResultsHuman footprint was found to be stronger in the state of São Paulo and other metropolitan areas, main cities in the countryside and coastal regions across the Atlantic Forest (Fig. 2A). Amphibian species richness varies throughout the Atlantic Forest (Fig. 2C). It is higher on the coastal regions, mainly at latitudes between 20 and 25 °South (∼80 to 130 species). Minimum monthly evapotranspiration is primarily higher on the countryside and Semideciduous portion of the Atlantic Forest, whereas it is lower on the coastal regions where Ombrophilous Forest remains (Fig. 2B).

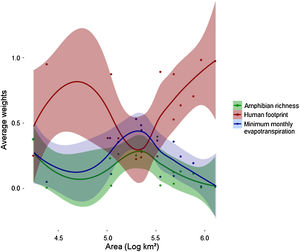

Human footprint was more important to predict Bd prevalence than the other two predictors for both smaller (104 km2) and larger scales (>106 km2) used in this study (Fig. 3). However, its relative importance (e.g., average weight) decreased and remained similar to that of the other predictors in intermediate scales (∼105 km2) and then increased again. At intermediate scales, minimum monthly evapotranspiration increased in importance and showed higher relative importance than the two others. At the same scale, relative importance of amphibian richness also increased, but remained lower than the other two variables. MMPE had the highest contribution to explaining Bd prevalence in intermediate scales and was slightly more important than amphibian richness for all scales, however the weights for all three predictors were not significantly different at that scale (Fig. 3, Table 1). Throughout the Atlantic Forest, amphibian species richness was the factor that had the least important contribution to Bd prevalence prediction. In intermediate sized regions, there was an increase in importance of amphibian richness in explaining Bd prevalence, but it remains less important than the others.

Average weights of each variable for each location, by area: amphibian richness (green), human footprint (red) and minimum monthly evapotranspiration (blue), for each spatial scale. Each dot accounts for one variable at a certain data point. Each datapoint has three components: average weight for each variable for each location. Areas are converted to log10, so 105 km² is equivalent to 5 in this graph. Values for each location can be found in Table 1.

Summary of model averaging results. The table shows the AIC weights of models explaining the prevalence of the chytrid fungus on wild amphibians, which were built according to different predictors (MMPE: minimum monthly potential evapotranspiration, HFI: human footprint, rich_amph: richness of host amphibians) and at different spatial scales, represented by the area (in Km2) of each Region, which represent different-sized spatial units.

| Region | Scale | Area (Km2) | Log Area | Average weights | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMPE | HFI | Richness | ||||

| Pernambuco Coastal Forest | Small | 17,496 | 4.240 | 0.376 | 0.250 | 0.375 |

| Campos Rupestres | Small | 24,057 | 4.380 | 0.050 | 0.949 | 0.006 |

| Bahia Coastal Forest | Small | 107,163 | 5.030 | 0.385 | 0.385 | 0.230 |

| Serra do Mar | Small | 110,079 | 5.040 | 0.110 | 0.873 | 0.021 |

| Bahia Interior Forest | Small | 223074 | 5.340 | 0.483 | 0.238 | 0.285 |

| Araucaria Forest | Small | 225,261 | 5.350 | 0.445 | 0.279 | 0.286 |

| Alto Parana Forest | Small | 480,411 | 5.680 | 0.358 | 0.527 | 0.125 |

| Northern Ombrophilous Forest | Intermediate | 130,491 | 5.110 | 0.355 | 0.383 | 0.262 |

| Northern Semideciduous Forest | Intermediate | 198,288 | 5.290 | 0.530 | 0.224 | 0.253 |

| Northern Atlantic Forest | Intermediate | 327,321 | 5.510 | 0.366 | 0.245 | 0.396 |

| Southern Ombrophilous Forest | Intermediate | 351,378 | 5.540 | 0.089 | 0.891 | 0.023 |

| Ombrophilous Atlantic Forest | Intermediate | 481,869 | 5.680 | 0.095 | 0.873 | 0.036 |

| Southern Semideciduous Forest | Intermediate | 566,433 | 5.750 | 0.244 | 0.635 | 0.130 |

| Semideciduous Atlantic Forest | Intermediate | 764,721 | 5.880 | 0.193 | 0.704 | 0.113 |

| Southern Atlantic Forest | Large | 918,540 | 5.960 | 0.015 | 0.982 | 0.007 |

| Atlantic Forest | Large | 1,278,666 | 6.100 | 0.019 | 0.973 | 0.011 |

Infectious diseases act synergistically with other factors to decimate native fauna populations worldwide, yet the main drivers of disease occurrence and prevalence remain poorly known (Heard et al., 2013; Stephens et al., 2016). Humans have profoundly altered the Atlantic Forest and dramatically reduced its pristine areas, mainly by habitat alteration, fragmentation and degradation (Marques and Grelle, 2021). In this study, we tested for the relative influence of biotic (host richness), abiotic (minimum monthly potential evapotranspiration) and anthropogenic (Human Footprint Index) factors in predicting the prevalence of the chytrid fungus on amphibian communities across a range of environmental gradients in the Atlantic Forest, while controlling for autocorrelation and scale-dependency.

Surprisingly, we found that human footprint index had the highest relative importance to explain Bd prevalence in most spatial scales, where Bd and HFI were positively correlated in different ecoregions and subregions of the Atlantic Forest of South America. Compared to HFI, host richness and minimum monthly potential evapotranspiration had smaller relative importance on explaining Bd distribution at most spatial scales. Our findings also suggest the notion that anthropogenic-driven modulation of Bd infection is scale-dependent, once the effect of HFI was indistinguishable from other drivers at intermediate scales. This may be a suggestion for future studies to explore the effect of anthropogenic threats in intermediary scales, since not much evidence is available on the scale at which anthropogenic threats affect biodiversity (Cohen et al., 2016).

Despite of our hypothesis that MMPE would have highest influence in large scales, we found MMPE to be less important than HFI in most of the studied spatial scales, in contrast to what has been found for the Americas (James et al., 2015). However, there was an expressive increase on MMPE relative importance at intermediate scales of analysis, and sudden decrease in importance in larger scales, the same pattern observed by Cohen et al. (2016). Those are interesting and contradict our hypothesis of climate being the main driver in large scales. They might suggest that in a highly altered biome such as the Atlantic Forest, human alterations might surpass climate variables in importance to explain pathogen occurrence.

Unfortunately, as it is common for tropical areas, we did not have enough prevalence records in the smallest ecoregions analysed and therefore we could not consider scales smaller than 104 km2. Thus, given the scale of analyses, it would be unlikely to detect the effect of biotic factors, even if they were highly correlated with chytrid prevalence, since species interactions are expected to be important in local scales (Willis and Whittaker, 2002). Further sampling effort in less studied regions of the Atlantic Forest such as the Northeast of Brazil can be of great value to fill the knowledge gap on the distribution of Bd in the region.

However, one key finding was that in larger scales HFI was more important to explain occurrence of Bd. We hypothesize two possible and non-exclusive mechanisms for the influence of HFI on Bd prevalence: 1) human altered habitats contain higher Bd prevalence because humans transport it to new areas through contaminated water and individuals species; and 2) human altered habitats affect amphibians’ immunological response, causing them to be unable to cope with the infection and spreading it. Humans can influence Bd prevalence via direct transportation and increasing propagule pressure in invaded regions (Fisher and Garner, 2020). In fact, the evidence therefore suggests that the global expansion of the distribution of the fungus happened through transcontinental commercial trade, highways and through the introduction of exotic amphibians in new sites when they are exported for food, research or collections (Fisher and Garner, 2020; Liu et al., 2013; O’Hanlon et al., 2018; Schloegel et al., 2012), which corroborates the anthropogenic mediation of its recent introduction elsewhere (Lips et al., 2003; Rödder et al., 2009).

On the other hand, human altered habitats can affect amphibians’ immunological response, causing them to be unable to cope with the infection and spreading it (Davidson et al., 2007). For example, the presence of pesticides in aquatic environments is related to immunosuppression and increased parasitism following pesticide exposure in amphibians (Christin et al., 2004; Rohr and Palmer, 2013). Moreover, human footprint has been associated with higher invasibility (Beans et al., 2012), suggesting that there may be biological mechanisms that facilitate the spread of invasive species in human-dominated landscapes. We argue that the two processes may act together, as transportation can bring the pathogen and human alterations in the environment can make hosts more susceptible to infection, both leading to a perceived increase in importance for HFI in explaining pathogen occurrence. This might be exacerbated in highly modified environments such as the Atlantic Forest, especially in south-eastern Brazil, where most of our data collections points are, there are many bullfrog farms (Ribeiro and Toledo, 2022) which are likely to impact susceptible native species through the release of Bd zoospores into the environment (Ribeiro et al., 2019).

Our findings challenge the expected effect of factors influencing species distribution, because climatic factors supposedly should prevail at larger spatial scales (Ricklefs, 1987; Willis and Whittaker, 2002), even though the scale in which anthropogenic effects influences biodiversity has not been widely tested (Cohen et al., 2016). After testing that, we found that in this study anthropogenic features of landscapes were more important than an important climate variable itself to explain the prevalence of the chytrid fungus across a wide range of landscapes from a biodiversity hotspot. The results found here, therefore, add to the mounting evidence that, at least for this particular fungus, anthropogenic factors can be even more important than classically analysed factors concerning the distribution of organisms such as biotic and climatic variables. It is, thus, urgent that the effects of human pressures are evaluated in time and space so we can mitigate the environmental damage posed to native faunas worldwide (Steffen et al., 2015).

Author contributionsJAS, LFT and LPS conceived and designed the study; LFT provided chytrid data; JAS and LPS gathered and compiled the data; JAS and LPS performed analysis; JAS, LFT and LPS drafted the manuscript. All authors provided input, approved the final version of this manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests statementAuthors declare no competing interests.

Grants and fellowships were provided by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP #2016/25358-3; #2019/18335-5), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq #300896/2016-6; #302834/2020-6), and by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES - Finance Code 001). We thank Mariana Nery for kindly allowing us to use her server in order to run statistical analyses.