Words and terms evoke responses in us, independently of their original meaning. Precise language matters because terminology can affect conservation. For example, current deforestation rates put the Amazon in the spotlight of global conservation, particularly after the “savannization of the Amazon” was proposed. This term associates cleared or degraded forests with savannas, reinforcing prejudices against natural savannas. The Cerrado is the world’s largest and richest savanna, but receives less conservation attention and resources. Firstly, we showed a multisector Cerrado neglect: number of protected areas, non-governmental organizations, academic human resources, and companies were larger in the Amazon, but deforested area was proportionally smaller. Secondly, we analyzed the academic use of “savannization of the Amazon.” In all 481 studies using this term, human action was implied, and most meant that degraded Amazon does not become old-growth savanna. We propose abandoning the use of “savannization of the Amazon”, promoting the support and attention the Cerrado needs.

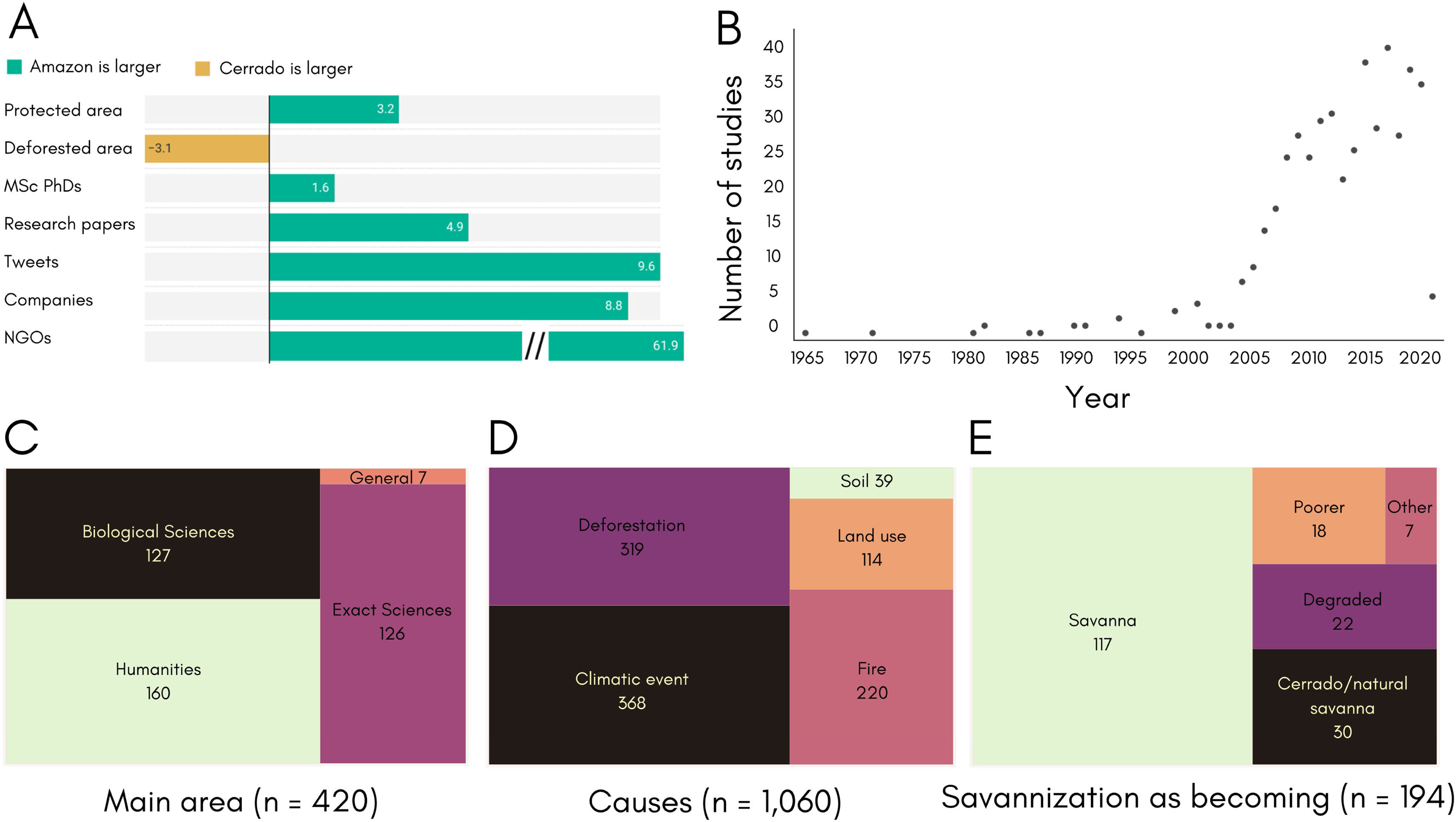

Words and terms evoke responses in us, consciously or not. Names like Tasselled Wobbegong (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon, Chondrichthyes) or Hummingbird Hawk-Moth (Macroglossum stellatarum, Insecta) can be fun and puzzling. Names with negative connotations like Sheep-eating Eagle or Killer whale, irrespectively of their original meaning, rouse less support for conservation of these species (Jacquet and Pauly, 2008; Karaffa et al., 2012; Sarasa et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2015). Here, we aim to discuss the prejudice of a term, the “savannization of the Amazon,” towards the protection of a whole biome, the Cerrado. We firstly expanded the information about the Cerrado neglect including multidisciplinary data beyond academia (Fig. 1A) and, secondly, analyzed the use of the term in scientific studies (Fig. 1B–E; Shirai, 2024).

(A) Multisector data showing how many times a biome has a factor larger than the other. Protected area: area in the Amazon (29% of its total area) and Cerrado (9% of its total area); source: CNUC. Deforested area: area in 2021, Level 0 data, for Anthropic category; source: MapBiomas. Master (MSc) theses and PhD dissertations: "Amazônia” (9,515) and “Cerrado” (5,926) in titles and keywords; source: Sucupira platform. Research papers in Restoration and number of social media Tweets from Silveira et al. (2021). Companies: “Amazon” (44) and “Cerrado” (5) in the company’s description; source: CrunchBase platform. NGO number: “Amazon” or “Amazônia” (867) and “Cerrado” (14) in keywords; sources: ONGsBrasil, idealist, wango, UN. Number of studies using the term “savannization of the Amazon” (B) by year (until March 2022); (C) by main area (for articles, conferences, and theses); (D) by causes, when mentioned; and (E) by those explicitly mentioning what savannization means. Detailed methods in the Suppl. Material.

Brazil is known to harbor the largest tropical rainforest in the world, the Amazon, which is one of the biologically richest places on Earth. But society does not seem to be equally aware that Brazil also holds the most extensive and continuous area of the richest savanna in the world, the Cerrado or Brazilian savanna, and the largest transitional forest-savanna mosaic (Oliveira and Marquis, 2002; Marques et al., 2020). The Cerrado was in fact even larger, and the Amazon smaller a few thousand years ago (e.g., Haffer, 1969). The number of Cerrado species can be similar (e.g., vertebrates; Myers et al., 2000) or larger (e.g., angiosperms; BFG, 2022) than in Brazilian rainforests, despite the assembly of its flora today being much more recent, with ∼10 million years (Simon et al., 2009).

The high richness, endemism, and threat in the Cerrado ranked it a global conservation hotspot (Myers et al., 2000), but that has not reflected in changes in investments and attention at the same pace as in Brazilian forests (e.g. Bispo et al., 2023). This gap was demonstrated in academic terms and in a social network, highlighting that “Biome Awareness Disparity is BAD” (Silveira et al., 2021). Here, we show that conservation efforts (NGOs and protected areas, PAs), academic human resources, and number of companies were larger in the Amazon, but deforested area was larger in the Cerrado (Fig. 1A).

The Cadastro Nacional de Unidades de Conservação provides official information of Brazilian PAs, listing 338 PAs in the Amazon and 461 in the Cerrado. However, in terms of area, 120.52 Mha are protected in the Amazon versus 17.85 Mha in the Cerrado, respectively, 29% and 9% of their total area. Considering strict legal protection, PAs drop to approximately a third of their total area (10.2% in the Amazon) which, for the Cerrado, means 2.7% of its total area, as similarly reported by Françoso et al. (2015).

An important aspect of academic bias is training of human resources. The Sucupira platform provides databases of all theses and dissertations defended in Brazil, from 1987 to 2021. We found more titles and keywords mentioning “Amazônia” than “Cerrado,” respectively, 6,697 and 4,285 for MSc level, and 2,818 and 1,641 for PhD level (Fig. 1A); with 309 studies mentioning both. The bias also appears in job opportunities, e.g., 814 positions opened in Brazil during 2023 (Science and Technology Ministry). Among the 17 institutions involved are National Research Institutes dedicated to investigate the biodiversity of Brazilian rainforests (INPA, for the Amazon; and INMA, for the Atlantic Forest), but there is no counterpart in the Cerrado – two institutes of this call that locate in the Cerrado do not specifically research the biome. There exists, though, an institute focusing on Agronomy research in the Cerrado (Embrapa). Unsurprisingly, 32% of all graduate output in the Cerrado (total: 5,926) are in Agricultural Sciences (18% for Amazon, total: 9,515).

The proportion of Restoration papers reported previously was larger for the Amazon, with social media Tweets being almost twice as large (Silveira et al., 2021). Our results revealed an even larger discrepancy regarding conservation efforts outside academia: NGO number showed the largest disparity (867 for the Amazon, 14 for the Cerrado). For entrepreneurships, CrunchBase private-sector platform showed a ∼9× larger presence of “Amazon” (44) in the company’s description than “Cerrado” (5).

The term “savannization in the Amazon” in scientific studiesThe impact of the negligence can be far-reaching. Recent deforestation studies in the Amazon have raised attention that points of no-return, or tipping points, are already happening (Lovejoy and Nobre, 2018, 2019), sooner than previously estimated (by 2050; IPCC, 2007). If a threshold is tipped, a chain of irreversible losses causes forest dieback, the so-called “savannization of the Amazon” (Oyama and Nobre, 2003). This term helped putting Brazil in the IPCC map, because of similar concerns about desertification in tropical Africa. Desertification and savannization are sometimes used interchangeably, meaning to become poorer, without distinguishing the biodiversity of deserts and savannas.

Savannization and desertification were both coined by the African forest expert André Aubréville (1949). The recent appropriation to the Amazonian context occurred within the Exact sciences (Oyama and Nobre, 2003; from ideas developed in Nobre et al., 1991). Several studies already called attention to the threat the term “savannization in the Amazon” poses to savanna conservation (Walter, 2006; Alvarenga, 2007; Hecht, 2007; Kageyama and Gandara, 2008; Sawyer, 2008; Veldman and Putz, 2011; Santos, 2013; Silveira et al., 2021). However, a formal evaluation of its usage is lacking, so we analyzed 481 scientific studies (267 in Portuguese and 214 in English) that used it (Shirai, 2024).

We observed a sharp increase in the number of studies using the term after 2007. The IPCC report (2007) probably was the trigger, with 87% of the studies appearing from 2008 onwards (Fig. 1B). We retrieved similar numbers of studies using the term among Biological (BS, 30%), Exact (ES, 30%), and Human (HS, 38%) Sciences (Fig. 1C, n = 420). Regarding Google Scholar citations, we found similar averages of citation number for BS (40) and ES (41), and smaller for HS studies (16). Among the 36 studies cited more than 100 times, 35 used savannization not as becoming Cerrado.

“Savannization in the Amazon” was attributed to climatic events, deforestation, and fire in 86% of studies that mentioned causes, with soil degradation and land use appearing less frequently (Fig. 1D, n = 453). The first three causes considered together was the most frequent combination (24%), appearing equally among main areas (20% BS, 23% ES, and 22% HS). It was closely followed by climatic events mentioned alone (21%), also with similar proportions among the main areas (22% BS, 21% ES, and 21% HS).

Every study implied human action causing the “savannization of the Amazon” and 94% of studies implied that it leads to degradation of the biota. Additionally, we categorized descriptions about the meaning of savannization in 194 studies (40% of the total database, Fig. 1E). The majority (117, or 60%) meant to become a loosely-defined savanna, which ranged from any kind of open area to a climatic savanna. In 30 studies, it meant to become a natural savanna; with 23 of them (12%) explicitly saying it would become a Cerrado. However, 13 of these 23 studies did not actually mean Cerrado as the biome or an old-growth savanna sensuVeldman et al. (2015a). A similar number of studies (22, or 11%) meant it as becoming a degraded, derived, secondary environment, including cattle fields.

Aside from forest degradation (due to deforestation, climate change, extreme droughts, frequent fires, overexploitation, etc.) aspect being evident in the vast majority of studies, 22 mentioned the dominance of invasive species. Finally, 18 studies (9%) explicitly used words related with impoverishment, and 6 (3%) related with desertification, usually as savannization being a step before desertification.

Abandonment of the termWe found a general understanding that the resulting biota after deforesting the Amazon is not that of an old-growth savanna. Hard evidence testing the savannization in situ is scarce but also points to that direction: in 14 studies (see Suppl. Material) addressing what the biota (mostly plants) turns into, almost none demonstrates that deforested Amazon becomes Cerrado as a functional ecosystem. Either the assembly is not of Cerrado species or, when it is, they are few or generalist species, which is expected given e.g. the unique association of Cerrado assemblies with edaphic conditions (Oliveira and Marquis, 2002). Studies outside the Brazilian Amazon also demonstrate that intensive land use and climate change do not lead to natural savannas (e.g., Borhidi, 1988; Cavelier et al., 1998; Dezzeo et al., 2004; Sansevero et al., 2020, but see Flores and Holmgren, 2021); including areas within the Cerrado, where abandoned pastures do not recover Cerrado vegetation (Cava et al., 2018).

When savannization was appropriated to the Amazonian context, it meant savanna as a climatic set of parameters (Salati et al., 2012), independent of its biotic composition, soil, complexity, or age. The term became broadly spoken after the IPCC report by the three main areas of knowledge (BS, ES, HS) that have different lexicons and sometimes-conflicting priorities. Despite these divergences, we found a general understanding that the “savannization of the Amazon” is a result of anthropogenic action, and leads to a degraded environment, and not Cerrado.

An open environment can be described in terms of climate, but the word savanna has multiple uses and connotations, including the idea of impoverishment and inferiority. If natural savannas are seen as poor places, then savannas would not be worth preserving. Even within peer-reviewed articles, we found imprecision by simply translating the secondary savanna resulting from savannization to Cerrado. Calling a climatically-defined or remote sensing-detected open area resulting from deforestation as “savanna” incites a confusion equating abandoned pastures with old-growth savannas (Putz and Redford, 2010; Veldman et al., 2015b), hampering the Cerrado conservation.

This confusion extends to other open areas (Bispo et al., 2023), including the Caatinga (Santos et al., 2011; Teixeira et al., 2021), pampas (Overbeck et al., 2007), Amazonian savannas (Devecchi et al., 2020) and campinas/campinaranas (Adeney et al., 2016). Some might also implicitly assume that any open ecosystem is already a modified, anthropic environment (Walter, 2006; Duvall et al., 2018; Buisson et al., 2021), and this “tameness” correlates with a perception of biologically poorer places (Hecht, 2007; Overbeck et al., 2015). Subtle and unspoken negligence like this often has historical Eurocentric roots in equating nature with forests, biasing the way we study and understand savanna conservation (Miller, 2005; Walter, 2006; Dias, 2008; Putz and Redford, 2010; Chazdon et al., 2016; Davis and Robbins, 2018; Pausas and Bond, 2018). An implication is that e.g. investments in forests were 168x higher than savannas: CrunchBase shows that investments in companies that provide service or products related to forests sum to 2.31 billion USD (201 funding rounds from 2000 to 2023), while to savannas they sum to 12.70 million USD (three funding rounds, from 2018 to 2023).

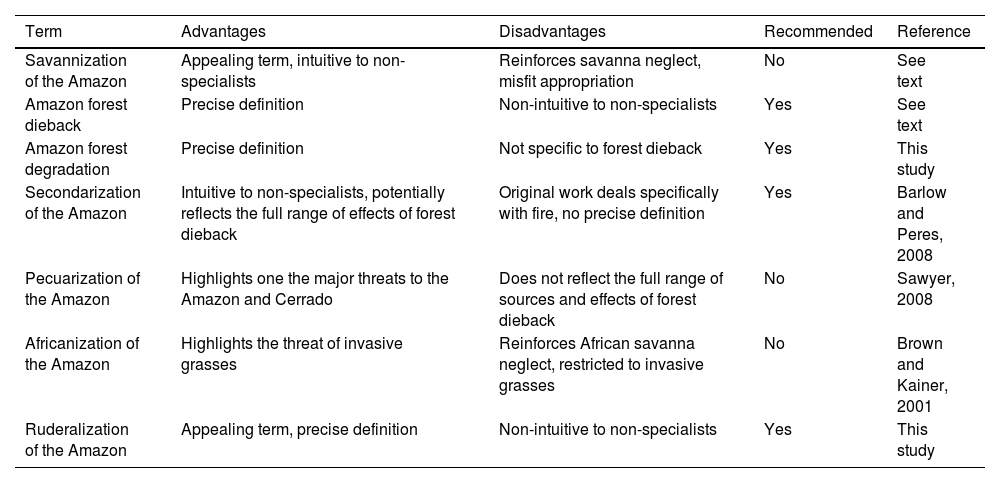

Passive and active bias against the Cerrado can critically put it at the risk of extinction. Scientists are frequently consulted by policy- and decision-makers about concepts independently of their robustness. Therefore, we urge society to understand that “savannization in the Amazon” is a term intersecting knowledge areas and many sectors and, as such, it has gained different interpretations so reaching a consensus is elusive. Other proposals, such as secondarization (Barlow and Peres, 2008), scrubfication/pecuarization (Sawyer, 2008) or even africanization (Brown and Kainer, 2001), do not represent the full range of savannization effects or do worse damage (Table 1).

Summary of alternative terms, their advantages, disadvantages, and our recommendation.

| Term | Advantages | Disadvantages | Recommended | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savannization of the Amazon | Appealing term, intuitive to non-specialists | Reinforces savanna neglect, misfit appropriation | No | See text |

| Amazon forest dieback | Precise definition | Non-intuitive to non-specialists | Yes | See text |

| Amazon forest degradation | Precise definition | Not specific to forest dieback | Yes | This study |

| Secondarization of the Amazon | Intuitive to non-specialists, potentially reflects the full range of effects of forest dieback | Original work deals specifically with fire, no precise definition | Yes | Barlow and Peres, 2008 |

| Pecuarization of the Amazon | Highlights one the major threats to the Amazon and Cerrado | Does not reflect the full range of sources and effects of forest dieback | No | Sawyer, 2008 |

| Africanization of the Amazon | Highlights the threat of invasive grasses | Reinforces African savanna neglect, restricted to invasive grasses | No | Brown and Kainer, 2001 |

| Ruderalization of the Amazon | Appealing term, precise definition | Non-intuitive to non-specialists | Yes | This study |

We propose abandoning the use of “savannization in the Amazon”, and that the substitute does not reinforce the natural savanna neglect (Table 1). There is no better or worse usage of savannization because the collateral damage will remain as long as the idea that a degraded forest turns into a savanna is incited. Meanwhile, we suggest an explicit description of what the authors mean (e.g., degraded secondary vegetation, modified open vegetation with generalist species), compensating the lack of a new term (potential substitutes are summarized in Table 1).

Precision in words can be the fine line between protecting ecosystems by integrating or neglecting non-forested areas. Instead of devaluing a neglected biome, we can find solutions for socioeconomic inclusion and value the uniqueness and complementarity of two of the biologically richest places on Earth. This is especially relevant at the transition zones that harbor the diversity of both biomes and are the first targets of “savannization.” All Brazilian biomes are under threat, but one must not be protected at the expense of the other.

Competing interestsOn behalf of all co-authors, I hereby declare we do not have any competing interests.

LTS thanks Asha Allam and Débora Joana Dutra for revising previous versions of the manuscript, and Jorge Abrahão de Castro, Mariana A. Stanton, Lucas A. Kaminski, Augusto H. B. Rosa, and Renato R. Ramos for valuable discussions. This work was supported by Instituto Lula (Pesquisação: Temas de Fronteira, Inclusão econômica e social nos distintos biomas brasileiros) and Dimension Sciences DS Bridges Program 2023 to LTS; National Council for Scientific and Technological DevelopmentCNPq 313986/2020-7 to FBB; CNPq (304291/2020-0) and São Paulo Research Foundation (Biota-FAPESP 2011/50225-3; 2021/03868-8) to AVLF; and The Botanics Foundation from Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh to RJT.