Brazil’s General Environmental Licensing Law (No. 15,190/2025) redefines environmental governance under the banner of “simplification” but effectively dismantles preventive safeguards. The law introduces self-declared licensing, automatic license renewals, and broad exemptions for agriculture and livestock, while restricting public participation. Although partial presidential vetoes removed some unconstitutional provisions, these vetoes may still be overturned by Congress. Key omissions, such as the absence of vetoes on Articles 7 and 9, preserve mechanisms that weaken oversight and accountability. Within Brazil’s decentralized system, where most authorizations are issued by state agencies, the law consolidates existing permissive practices and deepens regulatory asymmetry. This new framework lowers the national baseline for environmental protection, threatens biodiversity, and jeopardizes Brazil’s ability to meet international climate and biodiversity commitments. Instead of modernizing procedures or strengthening institutional capacity, the law normalizes shortcuts that externalize environmental costs and undermine democratic participation.

On August 8, 2025, Brazil enacted a general environmental licensing law No. 15,190/2025 (Brazil, 2025a), presented under the rationale of “simplification”, but widely interpreted as a dismantling of environmental licensing. The so-called “Devastation Law” creates broad exemptions, weakens licensing requirements, formalizes self-declared licensing, and reduces public participation to symbolic levels. Collectively, these measures undermine constitutionally mandated safeguards (Brazil, 1988).

The new law had been under discussion for nearly two decades and had already raised deep concern among scientists and policymakers. Prior to its approval, some studies warned that the proposed General Bill of Environmental Licensing, Bill No. 3,729/2004 (National Congress, 2020) and Bill No. 2,159/2021 (Federal Senate, 2021) would dismantle Brazil’s environmental safeguards, weaken impact assessments, and remove public participation from decision-making (Ruaro et al., 2022; Gomes and Braga, 2025; Weidlich, 2025). These analyses anticipated many of the provisions now enacted in Law 15,190/2025, including the creation of self-declared licenses (Athayde et al., 2022). The concerns once described as hypothetical have now materialized in the sanctioned text and in the selective presidential vetoes that followed.

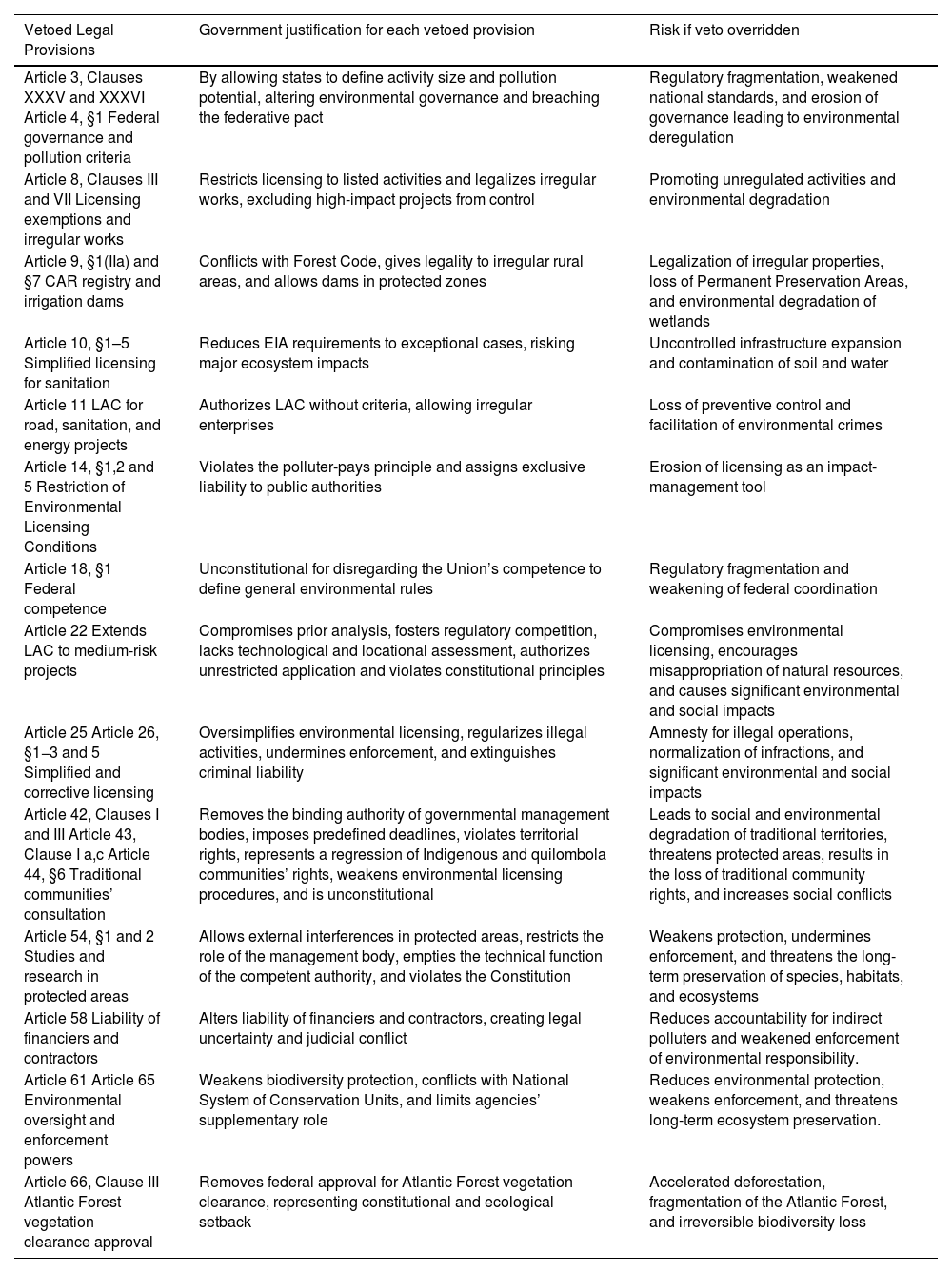

The President sanctioned the law but exercised vetoes on 63 provisions distributed across 19 articles, including paragraphs, clauses, and subparagraphs, either in their entirety or in part (Brazil, 2025b). These vetoes target the most damaging and unconstitutional provisions (Valle, 2020), including the expansion of licensing exemptions for agriculture and livestock, the automatic legalization of enterprises operating without prior authorization, restrictions on the participation of indigenous and quilombola peoples in licensing decisions, and those facilitating Atlantic Forest clearance. The vetoes also removed provisions that would have enabled arbitrary relaxation of licensing conditions and weakened mechanisms of technical evaluation and oversight. A summary of key vetoes and their implications is provided in Table 1.

Selected presidential vetoes to Brazil's General Environmental Licensing Law (Brazil, 2025b) and their implications.

| Vetoed Legal Provisions | Government justification for each vetoed provision | Risk if veto overridden |

|---|---|---|

| Article 3, Clauses XXXV and XXXVI Article 4, §1 Federal governance and pollution criteria | By allowing states to define activity size and pollution potential, altering environmental governance and breaching the federative pact | Regulatory fragmentation, weakened national standards, and erosion of governance leading to environmental deregulation |

| Article 8, Clauses III and VII Licensing exemptions and irregular works | Restricts licensing to listed activities and legalizes irregular works, excluding high-impact projects from control | Promoting unregulated activities and environmental degradation |

| Article 9, §1(IIa) and §7 CAR registry and irrigation dams | Conflicts with Forest Code, gives legality to irregular rural areas, and allows dams in protected zones | Legalization of irregular properties, loss of Permanent Preservation Areas, and environmental degradation of wetlands |

| Article 10, §1–5 Simplified licensing for sanitation | Reduces EIA requirements to exceptional cases, risking major ecosystem impacts | Uncontrolled infrastructure expansion and contamination of soil and water |

| Article 11 LAC for road, sanitation, and energy projects | Authorizes LAC without criteria, allowing irregular enterprises | Loss of preventive control and facilitation of environmental crimes |

| Article 14, §1,2 and 5 Restriction of Environmental Licensing Conditions | Violates the polluter-pays principle and assigns exclusive liability to public authorities | Erosion of licensing as an impact-management tool |

| Article 18, §1 Federal competence | Unconstitutional for disregarding the Union’s competence to define general environmental rules | Regulatory fragmentation and weakening of federal coordination |

| Article 22 Extends LAC to medium-risk projects | Compromises prior analysis, fosters regulatory competition, lacks technological and locational assessment, authorizes unrestricted application and violates constitutional principles | Compromises environmental licensing, encourages misappropriation of natural resources, and causes significant environmental and social impacts |

| Article 25 Article 26, §1−3 and 5 Simplified and corrective licensing | Oversimplifies environmental licensing, regularizes illegal activities, undermines enforcement, and extinguishes criminal liability | Amnesty for illegal operations, normalization of infractions, and significant environmental and social impacts |

| Article 42, Clauses I and III Article 43, Clause I a,c Article 44, §6 Traditional communities’ consultation | Removes the binding authority of governmental management bodies, imposes predefined deadlines, violates territorial rights, represents a regression of Indigenous and quilombola communities’ rights, weakens environmental licensing procedures, and is unconstitutional | Leads to social and environmental degradation of traditional territories, threatens protected areas, results in the loss of traditional community rights, and increases social conflicts |

| Article 54, §1 and 2 Studies and research in protected areas | Allows external interferences in protected areas, restricts the role of the management body, empties the technical function of the competent authority, and violates the Constitution | Weakens protection, undermines enforcement, and threatens the long-term preservation of species, habitats, and ecosystems |

| Article 58 Liability of financiers and contractors | Alters liability of financiers and contractors, creating legal uncertainty and judicial conflict | Reduces accountability for indirect polluters and weakened enforcement of environmental responsibility. |

| Article 61 Article 65 Environmental oversight and enforcement powers | Weakens biodiversity protection, conflicts with National System of Conservation Units, and limits agencies’ supplementary role | Reduces environmental protection, weakens enforcement, and threatens long-term ecosystem preservation. |

| Article 66, Clause III Atlantic Forest vegetation clearance approval | Removes federal approval for Atlantic Forest vegetation clearance, representing constitutional and ecological setback | Accelerated deforestation, fragmentation of the Atlantic Forest, and irreversible biodiversity loss |

Despite their importance, there are no guarantees that the vetoes will be maintained. According to the Brazilian Constitution, the Congress has the power to override presidential vetoes. Political initiatives to this effect are already underway, led by the Agriculture and Ranching Parliamentary Front (FPA, 2025), which holds majorities in both houses, the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. If successful, this override would further undermine environmental licensing, grant amnesty to environmental offenders, and erode constitutional guarantees.

Another way to circumvent the vetoes—and at the same time amplify the negative impacts of the law—was through the introduction of parliamentary amendments to Provisional Measure (MP) No. 1,308 of 2025 (National Congress, 2025). This measure seeks to alter Law No. 15,190/2025. Efforts to modify it began as early as August 11, just three days after the law was sanctioned, and by August 14, a total of 833 parliamentary amendments had been submitted. Only a small fraction of these amendments (95) sought to mitigate the setbacks (Climate Observatory, 2025).

This dispute transcends environmental policy. It represents an institutional stress test: if Congress overrides the presidential vetoes, it signals that the legislature can systematically impose institutional backsliding against the executive’s evaluation. Internationally, the stakes could not be higher. Overturning the vetoes would irreparably undermine Brazil’s credibility, exposing an irreconcilable gap between global commitments to sustainable development and domestic practices of nature conservation.

Brazil’s General Environmental Licensing Law: Approved and Consequences for ConservationDespite key vetoes, the enacted provisions already weaken licensing and pose serious risks to environmental conservation. The “Devastation Law” dangerously weakens the requirements and procedures for environmental assessments across all sectors. Under the guise of “development simplification”, it dismantles core regulatory mechanisms essential to protecting Brazil’s biodiversity, ecosystems, and the rights of people.

Although key presidential vetoes addressed some of the most critical points of the law, several provisions remained untouched. In particular, there was no veto to Article 9, which broadly exempts agricultural and livestock activities from environmental licensing. More precisely, the concern lies not with agriculture per se, but with some sectors of agribusiness, most associated with the large-scale production of commodities. Article 9 fails to establish clear thresholds or scales of production for which licensing is not required, particularly for crop cultivation. This omission opens a dangerous precedent for the expansion of medium- and large-scale intensive farming and livestock operations without adequate environmental oversight. Similarly, there was no veto to Article 17, which removes the requirement for municipal authorization for project implementation, further weakening local environmental governance.

Far from a simple policy misstep, this initiative represents a deliberate and perilous turn, one that accelerates large-scale environmental degradation and erodes the nation’s natural capital, thereby undermining the capacity of future generations to confront global change. Other critical omissions include Article 7, which authorizes the automatic renewal of environmental licenses through self-declaration. Together, these omissions further weaken preventive control and accountability mechanisms, amplifying the systemic erosion of environmental governance in Brazil.

Beyond these specific issues, the new General Environmental Licensing Law has profound implications for subnational practice, as most environmental authorizations in Brazil are issued by state and municipal agencies within the framework of the National Environmental System (SISNAMA). The decentralization of environmental licensing, reinforced by Complementary Law 140/2011 (Brazil, 2011), created a complex multilevel governance structure in which states define criteria and municipalities increasingly perform licensing for activities of local impact (Nascimento et al., 2020). While this system expanded administrative autonomy, it also exposed marked disparities in technical capacity, oversight, and political pressure among subnational entities. The new federal law consolidates these asymmetries; together, these provisions weaken preventive control and reinforce the deregulatory trajectory already observed in several states, where simplification measures and sectoral exemptions have advanced over the past decade (Bragagnolo et al., 2017).

However, the presidential vetoes on other provisions—such as those that would have extended LAC to medium-impact activities (Article 22) or simplified environmental assessments for strategic sectors (Article 10), impose partial restraints. These vetoes prevent the full normalization of self-declared licensing for higher-risk projects and formally preserve the principle of case-by-case environmental evaluation. In this mixed scenario, the law establishes a lower national baseline for environmental protection, consolidating permissive subnational practices where they already exist, while amplifying regulatory asymmetry and potential legal conflicts between levels of government.

We highlight the law’s critical flaws, which include Article 5 (LAC – self-declared licensing), Article 8 (loosening of controls for interventions), Article 14 and 16 (weakening conditionalities), Articles 18–21 (simplified and single-phase licensing with Environmental Impact Assessment – EIA, waivers even in high-risk projects), Article 24 (fast-track licensing for “strategic enterprises” such as mining, agribusiness, energy, and infrastructure), and Articles 39–41 (restricting public participation). Together, these provisions institutionalize environmental rollback by dismantling accountability, legitimizing self-declared compliance, curtailing public engagement, and substantially weakening EIA. By collapsing planning, installation, and operation into a single step, while prioritizing high-impact projects with limited scrutiny, the law signals that environmental responsibility is dispensable. This systematic dismantling is particularly alarming given Brazil’s global responsibility for biodiversity and climate governance (Rodrigues et al., 2025).

We are not opposed to improving Brazil’s environmental licensing system. On the contrary, we support efforts to streamline processes, reduce unnecessary bureaucracy, expand technical capacity, and increase transparency and training. These are meaningful and necessary steps toward modernizing licensing. However, the law fails to advance any of these goals.

Consequences for Biodiversity, Climate and Traditional CommunitiesBrazil, which has positioned itself as a global climate leader, will find it impossible to meet its nationally determined contributions and international environmental commitments under such conditions. The law directly undermines Brazil’s commitment to the Paris Agreement (United Nations, 2015) and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2022).

The impacts of this law will unleash a wave of environmental destruction that will be both immediate and irreversible. By dismantling safeguards within the assessment process, there will be an increase in native vegetation loss, habitat fragmentation, and land grabbing, and by consequence affecting the rich fauna associated. The legislation also facilitates one of the most damaging trends in coastal zones: predatory real estate development in coastal ecosystems. These ecosystems, already under critical threat, will face further pressure if entire sectors such as agriculture and livestock are exempted from environmental licensing, exacerbating landscape and biodiversity loss.

Even more alarming is the social cost, as the law effectively silences indigenous and traditional communities. Articles 42–44, partial vetoes, and Articles 45 e 46, no vetoes, establish restrictive procedures for the participation of affected authorities and peoples, limiting deadlines and making non-responses irrelevant. Thus, hollowing out the constitutional right to free, prior, and informed consultation. These communities, stewards of biodiversity and defenders of environmental rights, are now at risk under a law that privileges profit over life.

In response to these profound threats, we offer the following urgent and complementary recommendations - not as substitutes for preventive environmental governance, but as necessary strategies to counteract the weakening of licensing and participatory mechanisms:

1-Nationwide Environmental Monitoring Coalition. National networks of researchers, community leaders, journalists, and environmental Non-Governmental Organization must act as an independent observatory to document and denounce violations facilitated by the law.

2-Judicialization. The Federal Supreme Court and the Public Prosecutor’s Office are expected to challenge the constitutionality of provisions that eliminate EIA or enable self-declared licensing. These legal actions must highlight how such provisions undermine both environmental protection and democratic participation.

3-Citizen Lawsuits for Environmental Reparation. While prevention remains the cornerstone of environmental governance, the new law severely undermines the capacity of licensing procedures to fulfill this preventive function. In this context, it is essential not only to advocate for the reinstatement of robust preventive instruments but also to ensure that accountability mechanisms remain active and accessible. Public civil actions should be mobilized whenever biodiversity, ecosystem services, or nature’s contributions to people are seriously threatened or irreparably harmed as a direct consequence of the law’s implementation.

This constitutes a complementary legal strategy—capable of deterring further violations, establishing jurisprudential precedents, and securing effective reparation. These legal tools do not replace prevention; they reinforce it, particularly within a legal and institutional landscape where preventive safeguards are being systematically dismantled.

Beyond formal legal mechanisms, citizen mobilizations play a pivotal role in strengthening the social recognition of nature as a subject of rights, echoing ongoing movements and precedents in Brazil and elsewhere—such as initiatives recognizing the rights of entire ecosystems, from rivers to forests and mountains. These collective efforts broaden the ethical and institutional foundations of environmental protection, fostering a cultural transition toward viewing ecosystems as entities worthy of care, respect, and legal standing.

4-International Accountability. Multilateral environmental agreements, international financial institutions, and consumer-country regulations should enhance transparency to expose how licensing exemptions and weakened environmental controls feed global commodity chains linked to native vegetation loss and biodiversity decline. Strengthening environmental disclosure standards and due diligence mechanisms is essential to ensure accountability across borders.

ConclusionThe new Environmental Licensing Law (No. 15,190/2025) introduces significant setbacks for environmental governance in Brazil. By weakening preventive instruments, narrowing the scope of impact assessments, and easing requirements for agricultural and infrastructure projects, the law erodes decades of progress in regulating land-use change and biodiversity protection. Even without the parts that were vetoed, the version that came into force already reduces transparency, weakens public participation, and increases the risk of unchecked degradation, particularly in regions where enforcement is limited.

Presidential vetoes prevented an even deeper dismantling of Brazil’s licensing system. As summarized in the table, the vetoed provisions would have further curtailed Indigenous consultation, expanded automatic exemptions, and legitimized self-declared licensing for high-impact activities. Their maintenance now functions as a temporary safeguard against the most severe institutional and ecological consequences of the law. However, the fragility of these protections—subject to reversal by Congress—reveals how environmental governance has entered an unstable “gray zone” that depends more on political will than on coherent regulatory structure.

Moving forward, mitigating these risks will require complementary strategies that reinforce accountability and social engagement. Public civil actions and citizen lawsuits can deter violations and ensure reparation where environmental harm occurs, while social mobilizations can consolidate public recognition of nature as a subject of rights. Together, these legal and civic responses underscore that defending the remaining safeguards is not merely a procedural matter—it is essential to sustain Brazil’s ecological integrity, social justice, and credibility in global environmental commitments.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed equally to the development of the work.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve readability and language. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FundingWe thank the Brazilian Research Agencies Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), and Ministério de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação (MCTI) for essential financial support. We also thank the Associate Editor and two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.