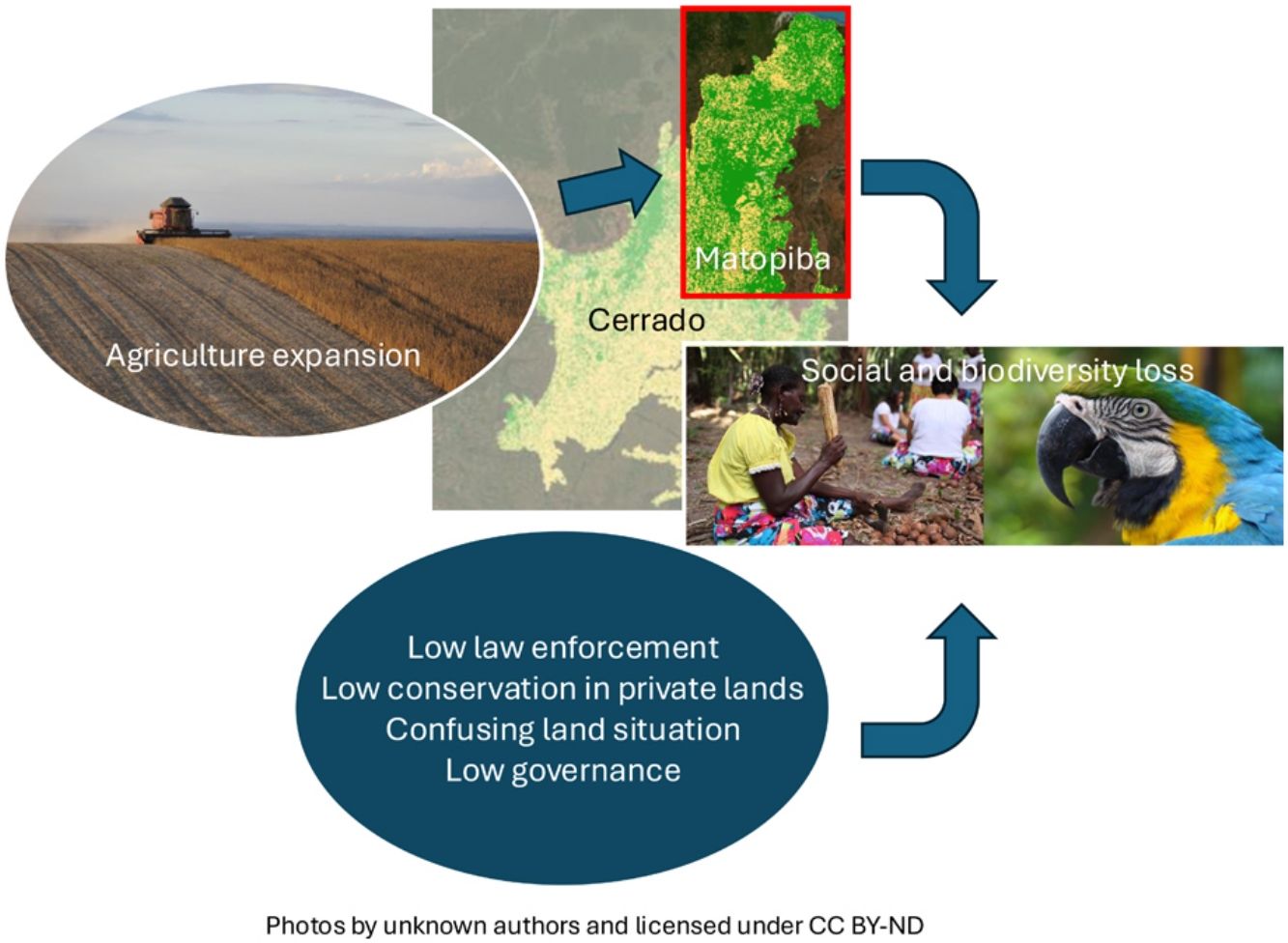

The Cerrado, the second largest biome in Brazil and home to nearly 5% of global biodiversity, has experienced a resurgence of devegetation due to the expansion of agribusiness activities. For the last two years, the devegetated area was more than one million hectares per year, surpassing the suppressed vegetation in the Amazon for the same period. Thus, the biome that is already the most impacted in Brazil is rapidly going to a critical tipping point of conservation, when conservation actions, like habitat restoration and species management, will be inviable due to the high cost. Such a situation results from political decisions taken years ago to expand the agricultural frontier to its northern portion, where environmental and social impacts are of high concern. We argue that a new development model is urgently needed to be implemented in the region with most of the remaining natural area.

The rapid and uncontrolled devegetation (vegetation removal) observed in the Brazilian Cerrado over the last four years, particularly in its northern region (known as MATOPIBA, an acronym which includes the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, Bahia) (Miranda et al., 2014), raises serious concerns about the biome's future and local communities. Data from the TerraBrasilis system, managed by the National Institute of Spatial Research – INPE, indicates a staggering 1.1 million hectares of devegetation in 2023 alone, equivalent to 12 times the size of São Paulo, the largest city in South America. Last year, the Amazon Rainforest, twice the size of the Cerrado, had 750,000 hectares deforested. The global focus on forest conservation has inadvertently led to overlooking the importance of the unique biodiversity and ecosystem services provided by non-forested ecosystems, such as the Cerrado (Bispo et al., 2024). Despite being Brazil's most devegetated biome, it has already lost an area equivalent to the size of Bolivia or Egypt, i.e., more than 1 million km2 to date and being home to nearly 5% of the global biodiversity (Machado et al., 2023), the Cerrado is rapidly approaching a critical point of biodiversity loss with additional significant social impacts. This disparity highlights the urgent need for greater recognition and conservation efforts for non-forested ecosystems like the Cerrado, considered a global biodiversity conservation hotspot (Mittermeier et al., 2004).

Furthermore, despite the Cerrado's importance in agricultural productivity and biodiversity, public policies reinforce the priority for forest conservation, as evidenced by efforts to create and maintain protected areas. Although the Cerrado is Brazil's second most protected region, with 12.15% of the original area maintained by protected areas (including indigenous lands), most of the non-protected areas are privately owned (Colman et al., 2024). Nevertheless, nearly half of the private properties in the Cerrado have failed to maintain the minimum legally required percentage of natural vegetation (Rajão et al., 2020), resulting in 5.4 million hectares that needed to be restored by private landowners (Bispo et al., 2024).

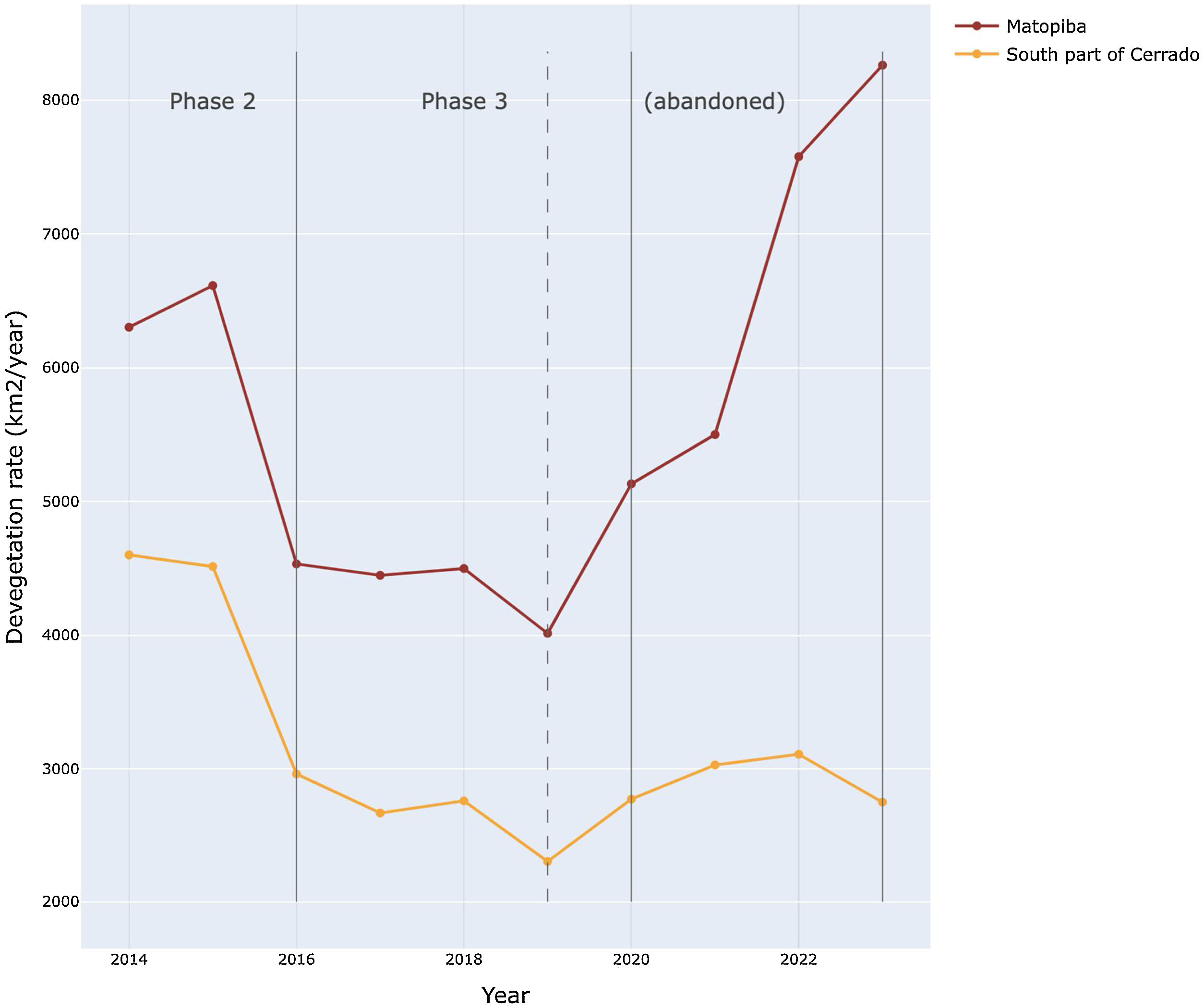

Approximately 75% of the total devegetation recorded in the Cerrado in 2023 was concentrated in the states of Maranhão (26.6%), Tocantins (20.3%), Bahia (17.9%), and Piauí (10.2%) — collectively known as the MATOPIBA region (Fig. 1). This trend contrasts sharply with the overall tendency of diminishing devegetation observed in other parts of the Cerrado, such as the southern region (Fig. 2). This stark contrast can be attributed to political decisions made several years ago.

Evolution of devegetated areas in MATOPIBA since 2014 (upper line), when the region was officially designated as "a new agricultural frontier", compared to the rest of the Cerrado biome (lower line). Devegetation decreased until 2019, during phases 2 and 3 of the Action Plan to Prevent and Control Devegetation and Fires in the Cerrado biome (PPCerrado), which was abandoned by the previous Government in 2019 (dashed line).

Studies conducted by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation – EMBRAPA (Miranda et al., 2014), the Federal Government declared the MATOPIBA region as a new agriculture frontier, with potential cooperation plans with Japan and the involvement of foreign investments, including pension funds engaged in land speculation (FIAN et al., 2018). The EMBRAPA’s study suggested that “there were no significant devegetation, but rather changes in land use and tenure.” However, the soybean plantations had already encompassed 4.8 million hectares across the four states of MATOPIBA, yielding 18.5 million tons in 2022. The current environmental and social situation reflects the consequences of this strategic choice, essentially replicating the development model that devastated the southern Cerrado. Despite the legal requirement for maintaining legal reserves and permanent preservation areas, as stated in the Native Vegetation Protection Law (Brazil, 2012), the southern portion of the Cerrado currently has a deficit of native vegetation to be restored (Bispo et al., 2024).

Why is it so easy to undergo devegetation in the Cerrado? Several factors contribute, but the land tenure situation in the northern Cerrado plays a crucial role. Agribusiness entrepreneurs and land-grabbers exploit the region's land tenure fragility, facilitating rapid occupation. Traditional communities in the area historically utilized lowlands (areas along watercourses) for subsistence agriculture, while plateaus or higher grounds were communally used for extensive cattle ranching without individual ownership or land titles (FIAN et al., 2018). The same plateaus traditionally used by local communities for subsistence became the agribusiness ‘fillet mignon’ because of the arable areas with a high potential for cropland mechanization.

The issue is that MATOPIBA is not just a land of opportunities and economic expansion. Still, it is a continuous natural area of Cerrado, but as a collection of diverse territories with distinct histories, sharing many transition zones to other biomes and a plurality of ecological subdivisions (Françoso et al., 2019; Russo Lopes et al., 2021; Sano et al., 2019), an aspect that ensures a rich and still unknown biodiversity. To illustrate this point, a 29 days scientific expedition conducted in 2008 by researchers from different universities in Brazil and supported by the NGO Conservation International, visited the Serra Geral do Tocantins Ecological Station, located in the very heart of MATOPIBA. They registered a total of 440 vertebrate species. Among them, they found 14 new species for science, including frogs, rodents, fishes, and a legless lizard (https://rb.gy/qxwc02).

Interestingly, these shared characteristics were highly relevant in the decision-making process regarding frontier formation by the agribusiness sector as a whole, including an abundance of legally ambiguous public lands and a cheaper land market, lower urbanization rates, higher poverty rates compared to the national average, and a peripheral position relative to the country's economic and political centers (Agostinho et al., 2023). Agribusiness entrepreneurs have capitalized on these circumstances, identifying prime land (flat lands with deep, well-drained soil) for highly mechanized crop production. According to SIDRA-IBGE data, soybean production in MATOPIBA increased by 122%, with a 102% increase in planted area between 2011 and 2022. In contrast, traditional soybean-producing states in the South (Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná, and Santa Catarina) experienced a 12% decrease in production during the same period despite a 41% increase in planted area. An indicator of agribusiness's impact in the region is the production of beans, a typical crop for small traditional producers. In the same period, bean production in MATOPIBA decreased by 31%, with a 23% decrease in planted areas (IBGE, 2021).

The situation in MATOPIBA requires close attention from authorities to enforce various public policies. The region is suffering expressive environmental and social impacts, even considering its current level of protection. Compared to the southern part of the Cerrado, where the legally created protected areas represent 8.31% of the original vegetation (Françoso et al., 2015), MATOPIBA has 20.55% protection by public areas. Such proportions include the largest strict protection areas of the biome, like the Nascentes do Parnaíba National Park (7,297.44 km2) and the Serra Geral do Tocantins Ecological Station (7,070.78 km2). The environmental solution and biodiversity conservation for the region is way beyond the simple creation of public protected areas. A broader action plan must urgently include the necessary social and environmental safeguards.

The challenges faced by traditional communities in MATOPIBA highlight a process of gradual strangulation rather than direct expulsion. Industrial agriculture has encroached on the plateaus historically used by these communities, leading to ecological conflicts such as reduced water availability, loss of native species, pesticide contamination, and loss of traditional cultivation areas. The lack of basic infrastructure and income-generating opportunities has forced communities to sell their lands or move to municipal centers (Russo Lopes et al., 2021). According to the Pastoral Land Commission (Pinto, 2023), there were 2,200 land conflicts in Brazil in 2023, involving more than 750 thousand people (63% belonging to traditional communities or indigenous people) and an area close to 60 million hectares. Around 32% of the land conflict had farmers, ranchers, or land grabbers as the source of the disputes. Maranhão and Bahia states rank as the second and the third states with all land conflicts. Recent studies suggest that the northern Cerrado is biologically distinct from the southern portion, harboring unique animal plant species (Françoso et al., 2019) and their ecosystem services (Sano et al., 2019; Aguiar et al., 2024). Such aspect justifies more urgent and compelling actions by the Federal Government and rural producers, who must engage in conservation efforts.

In 2010, the Brazilian Government launched the first phase of a plan to reduce and prevent devegetation in the Cerrado, called the PPCerrado (Brasil, 2023). The strategies involved law enforcement, protected areas, land-use planning, support for sustainable activities, and environmental education. Since the 1st Edition of PPCerrado, municipalities composing the MATOPIBA region were elected as top priority areas, i.e., regions for the implementation of the components of the plan.

The PPCerrado is now in its 4th Edition (2023–2027), and the plan seemed to work relatively well until 2019, when devegetation dropped. The devegetation dropped around 9% during the 1st Edition of the PPCerrado (2010–2011), 42% during the 2nd Edition (2014–2015) and 3rd Edition (2016–2020) (https://rb.gy/wzmz2r).

However, under the last federal administration (2019–2022), the previous government, notoriously indifferent to environmental issues, demonstrated a complete lack of commitment to environmental preservation and social issues throughout Brazil. Deforestation in MATOPIBA exploded after 2019, when the plan was abandoned (Fig. 2). This information indicates that law enforcement alone is insufficient to save what is left of the Brazilian Cerrado, and perhaps a new economic model, environmentally responsible and socially fair, is necessary for the region.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.