This paper adopts the Ansel & Gash (2008) model of collaborative governance to frame the structure of community-based trophy hunting (CBTH) programs as a form of collaborative governance that involves multiple stakeholders in the management of common pool resources. We conduct a meta-synthesis of 80 published studies on community-based conservation (CBC) and CBTH programs and develop contingency propositions that may help practitioners and governments to understand and implement programs that seek environmental conservation in collaboration with local communities.

Regarding the initial conditions to engender CBTH in developing countries, we propose that the failure of conventional top-down conservation policies, perception of local communities about potential benefits from CBTH, and existence of facilitative leadership, such as local or international conservation NGOs will play critical roles in initiating CBTH, even under the prehistory of conflict, power imbalance, and lack of trust.

We also propose organic and instrumental leadership from community and government and inclusive design that creates ground rules and basic protocols are important outside factors to induce stable and strong commitment from participants during the collaboration process.

Inside collaborative process, constructive, trust-building face-to-face meetings and generation of intermediate outcomes are identified as crucial factors to building a momentum for successful CBTH outcomes.

Community-Based Trophy Hunting (CBTH) has been promoted as an effective tool for conservation of endangered animals in developing countries since 1980s, which led to the growth of trophy hunting industries mostly in Africa and central Asia (Adams, 2008; Adams & Hulme, 2001; Baldus, 2009; Khan, 2012; Lichtenstein, 2010; Lindsey et al., 2007; Mayaka et al., 2005; McIntosh & Renard, 2010; Mir, 2006; Schumann, 2001; Shackleton, 2001; Twyman, 2000). The simple theory behind CBTH is that economic benefits from trophy hunting will incentivize local communities to be engaged as key partners with policymakers and practitioners to make efforts to conserve endangered species, and community members will do better than government since, by virtue of their proximity to and knowledge of wildlife, they are instrumental in detecting, reporting on, and helping preventing illegal wildlife trafficking (Baldus, 2009; Biggs et al., 2017; Li, 2002; Shackleton, 2001; Twyman, 2000).

Countries with reported successful cases of CBTH in Africa and Asia include Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania, Pakistan and Tajikistan. In these countries, CBTH has substantially increased the number of target mammals (Baldus, 2009; Damm, 2008; Frost & Bond, 2008; Lindsey et al., 2007; Mayaka et al., 2005; Shackleton, 2001; Zafar et al., 2014). The Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) in Zimbabwe was the first program that recognized wildlife as renewable natural resource, while addressing the allocation of its ownership to indigenous peoples in and around conservation protected areas (Taylor, 2009). The Southern Luangwa Valley Integrated Resource Development Project (LIRDEP) in Zambia and the Selous Conservation Programme (SCP) in Tanzania are among those initiated in the late 80 s. Similar programmes initiated in Namibia in the late 90 s followed by multiple attempts in South Africa (Baldus, 2009).

Despite several successful cases of CBTH around the world, CBTH still remains more theory than reality in many countries (Baldus, 2009; Goldman, 2003; Shackleton, 2001). Many commentators ascribe failures of CBTH to ineffective governance in and around CBTH and suggest better governance for successful CBTH (Balint & Mashinya, 2006; Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Damm, 2008; Lichtenstein, 2010; Newig & Fritsch, 2009; Paudyal et al., 2017). Factors related to ineffective governance include inadequate legislation in implementing community participation (Baldus, 2009; Lichtenstein, 2010), conflict among stakeholders on the level of participation (Balint & Mashinya, 2006), state’s influence in selecting participants (Lebel et al., 2008), power imbalance among community members (Twyman, 2000), lack of reliable information on the economic significance and ecological impact of the hunting industry (Lindsey et al., 2007), and corruption leading to inequitable distribution of revenues from trophies (Baldus, 2009; Khan, 2012; Lindsey et al., 2007; Nagendra & Ostrom, 2012).

Thus, effective and collaborative governance matters for successful CBTH where power is transferred from state to local community and empowered community members participate actively and collaborate with various stakeholders including government agencies, donor institutions, private corporations and experts. Such a collaborative setting enables participants to build trust and own decision-making processes, and ultimately manage the stock of endangered wildlife in a sustainable way (W. M. Adams & Hulme, 2001; Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Folke et al., 2005; Goldman, 2003; Mackenzie, 2010; Mayaka et al., 2005; Newig & Fritsch, 2009; Paudyal et al., 2017; Seixas & Berkes, 2010; Taylor, 2009).

Despite much literature on governance components of community-based programs, a clear framework to guide, monitor, and assess CBTH programs however is lacking. Such a framework is essential to facilitate appropriate preparation and implementation of CBTH programs on the ground. Thus, to address this gap, this paper intends to elaborate a general governance model by framing CBTH as a form of collaborative governance and by conducting a meta-synthetic study of the existing literature on common-pool resource management (CPRM), CBC, and CBTH programs. Ultimately, this study contributes to the existing literature by developing a contingency approach to collaborative governance and identifies conditions for determining the effectiveness of CBTH programs.

In this study, we refer to the Ansell and Gash (2008) model that defines collaborative governance as “a governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets.” Many characteristics of CBTH match with the components of collaborative governance defined above. In a CBTH program, public agencies engage various non-state actors such as International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), in formal and collective decision-making processes where participants deliberate and negotiate for joint agreement to conserve endangered mammals through trophy hunting mechanism.

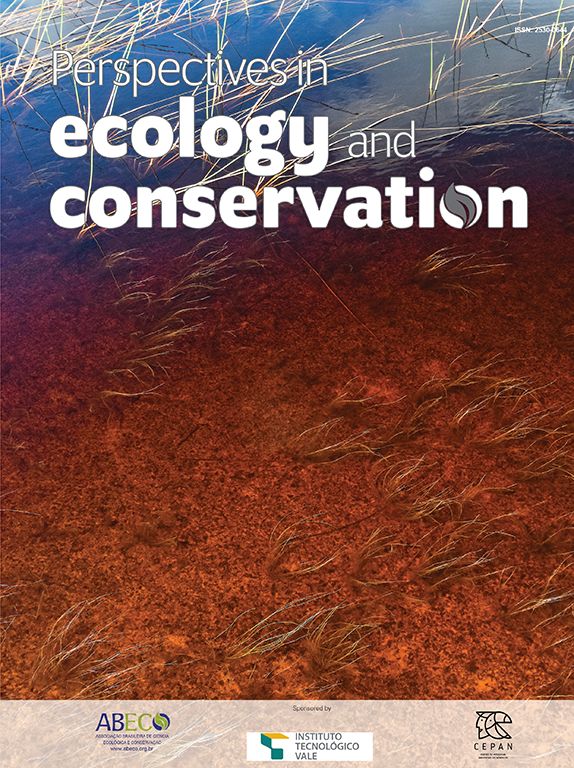

The core system components of collaborative governance model by Ansell and Gash (2008) include starting conditions, institutional design, facilitative leadership, collaborative process and outcomes (Fig. 1). In the following sections, we explain the research method briefly, discuss what we found in literature on CPRM, CBC, and CBTH programs in conjunction with the model of Ansell and Gash (2008), and try to tailor the model to the context of CBTH programs.

A Model of Collaborative Governance (Ansell and Gash, 2008).

To understand the initial structure of CBTH programs, in line with Ansell & Gash (2008), we conduct a meta-theoretical synthesis by exploring the factors that affect the structure of natural resource conservation programs from community participation viewpoint. We define the existing structure of CBTH programs as an institutional design that affects the process of conservation programs, in order to explain the behaviors of stakeholders during the process of collaboration and implementation. In analyzing the environment of community-based natural resource management programs, we draw on the Ostrom’s conceptual unit called an “action situation” that enables us to describe, analyze, predict and explain behaviors of stakeholders within institutional arrangements (Ostrom, 2011). According to Ostrom (2011), an action situation is a social space where individuals and actions are assigned to positions that are linked to potential outcomes. In social-ecological context, an action situation involves interactions of stakeholders in light of the incentives they face to generate outcomes. We then adopt a meta-synthetic methodology to integrate results from different inter-related qualitative studies in common-pool resource management and community-based conservation in general and CBTH in particular.

To search for published cases on CBC and CBTH, a conventional literature search was undertaken that included academic journals, book chapters, and published reports across a wide range of disciplines, such as ecology, conservation, economics, governance, and environment. In our search, we used multiple key words, such as “conservation and development”, “community-based trophy hunting”, “collaborative governance”, “sustainable conservation”, “participatory governance”, and “common-pool resource management”. Although our main interest was in CBTH, we expanded the scope of our case studies to wildlife conservation where economic benefits of natural resource stock were strongly associated with local people’s livelihood. Our search identified 80 cases, projects and programs of community-based trophy hunting and conservation in published articles and reports since 1961. Details of these cases that include information about country, year of program implementation, type of conserved animals and collaborating or funding agency are shown in Appendix Table 1.

Community Based Trophy Hunting and Conservation Cases.

| S.No | CBTH Program and Region | Country | Year | Name of Animal/Birds | Funding | Journal and publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Luangua Integrated Resource Development Project (LIRDP | Zambia | 1988 | Elephant Ivory | Wildlife Conservation Revolving Fund(Initial Revenue distribution:40%: Management Cost35%: Local Community 25%: Government ) | Leader Williams, N., Kayera, J. A., & Overton, G. L. (1996). Community-based conservation in Tanzania; proceedings of a workshop held in February 1994. IUCN, Gland (Suiza). Species Survival Commission |

| 02 | Zambia Wetland Project | Zambia | 1986 | Elephant Ivory | WWF/IUCN | Chabwela, H., & Haller, T. (2010). Governance issues, potentials and failures of participative collective action in the Kafue Flats, Zambia. International Journal of the Commons, 4(2). |

| 03 | The Culman Wildlife Project (CWP) | Tanzania | 1990 | Wildebeest, Zebra, Buffalo and Impala | INGOs | Safaris, Tanzania Game Tracker, and Robin Hurt Safaris. "The Cullman Reward and Benefits Scheme." This volume (1996). |

| 04 | The Dorobo Tours and Safari Projects | Tanzania | 1990 | wildebeest, gazelle, zebra | Wildlife Department | Leader Williams, N., Kayera, J. A., & Overton, G. L. (1996). Community-based conservation in Tanzania; proceedings of a workshop held in February 1994. IUCN, Gland (Suiza). Species Survival Commission. |

| 05 | Oliver’s Camp Community Conservation Initiative | Tanzania | 1992 | Elephant | Wildlife Department | Leader Williams, N., Kayera, J. A., & Overton, G. L. (1996). Community-based conservation in Tanzania; proceedings of a workshop held in February 1994. IUCN, Gland (Suiza). Species Survival Commission. |

| 06 | TANAPA Community Conservation | Tanzania | 1985 | zebra, wildebeest, buffalo and elephant | INGO(African Wildlife Foundation) | Kangwana, K., & ole Mako, R. (1998). The impact of community conservation initiatives around Tarangire National Park (1992-1997). Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester. |

| 07 | Communal Area Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) | Zimbabwe | 1988 | Elephant Ivory, Zebra, Lion, | Government + INGOs(Revenue Distributionbenefits to Wards: 50% local community, 15 % government levy & 35% Project Maintenance and promotion) | Child, B. (1996). The practice and principles of community-based wildlife management in Zimbabwe: the CAMPFIRE programme. Biodiversity & Conservation, 5(3), 369-398. |

| 8 | Community-Based Natural Resource ManagementAnd Tourism: Nata Bird Sanctuary, Botswana | Botswana | 1993 | Birds: kingfishers, eagles, bustards, and ostriches as well as numerous woodland bird speciesMammals:hartebeest, kudu, reedbuck,springbok, springhares, jackals, foxes, eland, gemsbok,zebras, monkeys, and squirrels | Government | Stone, M. T., & Rogerson, C. M. (2011). Community-based natural resource management and tourism: Nata bird sanctuary, Botswana. Tourism Review International, 15(1-2), 159-169.Stone, M. T., & Nyaupane, G. (2014). Rethinking community in community-based natural resource management. Community Development, 45(1), 17-31. |

| 09 | The Koakoveld Community based Conservation Project(Kunene region) | Namibia | 1982 | Elephant, Black rhino, Giraffe, plains and mountain zebra, Kudu, gemsbok, impala, springbok, duiker, steenbok, klipspringer,, dik dik and warthog | WWF/IUCN + Local NGO | Kiss, A. (2004). Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends in ecology & evolution, 19(5), 232-237. |

| 10 | Mburo National Park Community Conservation Programme(CCP) | Uganda | 1992 | impala Aepyceros melampus, eland Taurotragus oryx and zebra Equus burchellii | Government | Infield, M., & Namara, A. (2001). Community attitudes and behaviour towards conservation: an assessment of a community conservation programme around Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda. Oryx, 35(1), 48-60. |

| 11 | Community-based Natural Resource management Programme in Western Botswana(Kalahari and Okwa Wildlife management areas) | Botswana | 1986 | Elephant, Giraffe Mountain Zebra, Dik-dik, Black-faced Impala, | government funded | Twyman, C. (2000). Participatory conservation? Community‐based natural resource management in Botswana. The Geographical Journal, 166(4), 323-335. |

| 12 | Ehi-rovipuka Conservancy under a national Community-Based Natural Resource Management Programme (CBNRM) that | Namibia | 1990 | Elephant, springbok, oryx, and kudu | government funded | Hoole, A., & Berkes, F. (2010). Breaking down fences: Recoupling social–ecological systems for biodiversity conservation in Namibia. Geoforum, 41(2), 304-317. |

| 13 | The Chobe Enclave Community Trust, a community living adjacent to Chobe National Park in Botswana | Botswana | 1984 | Elephant | WWF + Government | Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2-3), 166-184. |

| 14 | Mountain Areas Conservancy Project Chitral Region- Pakistan | Pakistan | 1999 | Markhor and Ibex trophies | UNDP & GEF | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 15 | The Torghar conservation project: management of the livestock, Suleiman markhor (Capra falconeri) and Afghan urial (Ovis orientalis) in the Torghar Hills | Pakistan | 1986 | Suleiman markhor, Capra falconeri megaceros, and the Afghan urial, Ovis orientalis cycloceros, | Mainly financed by the sale of trophies.Small grants were provided by the World Wildlife Fund-Pakistan, the Houbara Foundation, Safari Club International and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Small Grants | Woodford, M. H., Frisina, M. R., & Awan, G. A. (2004). The Torghar conservation project: management of the livestock, Suleiman markhor (Capra falconeri) and Afghan urial (Ovis orientalis) in the Torghar Hills, Pakistan. Game and Wildlife Science, 21(3), 177-187. |

| 16 | Community based Trophy Hunting Program (CTHP)-Northern Areas of Pakistan | Pakistan | 1996 | Himalayan Ibex, Markhor | WWF-Pakistan & IUCN-Pakistan | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 17 | Khunjerab village Community based Trophy Hunting Organization | Pakistan | 1995 | Marco-polo sheep, ibex, blue sheep, and snow leopard | IUCN- Pakistan | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 18 | Community based Conservation and Trophy Hunting of Ibex in Khyber Valley- Northern Pakistan | Pakistan | 1990 | Ibex | Community Driver Funding(under MACP) | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 19 | Community based Conservation and Trophy Hunting of Ibex in Basho Valley-Northern Pakistan | Pakistan | 1995 | Ibex | Government Forest Department | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 20 | Community based Conservation and Trophy Hunting in Bunji-Northern Pakistan | Pakistan | 1996 | Markhor | IUCN | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 21 | Community based Conservation and Trophy Hunting of Blue Sheep in Shimshal ValleyPakistan | Pakistan | 1989 | blue sheep and ibex | Japanese Government | Mir, A. (2006). Impact assessment of community based trophy hunting in MACP areas of NWFP and Northern Areas. Report for the Mountain Area Conservancy Project, IUCN Pakistan. |

| 22 | Pendjari National Park: A protected area benefitting local communities in Benin | Benin | 1986 | ion, African elephant, buffalo and leopard | German cooperation for many years (GTZ and KWF) and the French Global Environment Facility | IUCN(2011), A protected area benefitting local communities in Benin.https://www.iucn.org/ru/node/8509?amp;= |

| 23 | Governing Biodiversity and Livelihoods around the W National Parks of Benin and Niger | Benin And Niger | 1990 | Elephants, ungulates, western topi, the cheetah, West African manatee | World Bank, UNDP and German Aid(30% revenues go to the village organization) | Miller, D. C. (2013). Conservation legacies: governing biodiversity and livelihoods around the W National Parks of Benin and Niger (Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan). |

| 24 | Okavango Delta community trust based conservation | Botswana | 2014 | cheetah, white rhinoceros, black rhinoceros, African wild dog and lion | UNESCO | STATE OF CONSERVATION REPORT OKAVANGO DELTA NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE, BOTSWANA |

| 25 | Participatory forest conservation and sustainable livelihoods: banyang-mbo wildlife sanctuary | Cameroon | 1996 | Forest elephants | Government | (www.fao.org/docrep/ARTICLE/WFC/XII/0630-C1.HT )Social Scientist/Senior Community-based Conservation Officer, Wildlife Conservation Society/ Cameroon Biodiversity Programme, Banyang Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary Project; P.O. Box 20 Nguti, South West Cameroon. Tel: +237 220 26 45; +237 794 85 25; Email: lnkembi@yahoo.com |

| 26 | The influence of institutions on access to forest resources in Cameroon: The case of Tofala Hill Wildlife Sanctuary | Cameroon | 2014 | Africa’s most threatened great ape, the Cross River gorilla | Fauna & Flora International (FFI) | Nkemnyi, M. F., De Herdt, T., Chuyong, G. B., & Vanwing, T. (2016). The influence of institutions on access to forest resources in Cameroon: The case of Tofala Hill Wildlife Sanctuary. Journal for nature conservation, 34, 42-50. |

| 27 | Participatory approaches towards forestconservation: The case of LobekeNational Park, South east Cameroon | Cameroon | 2006 | ‘charismatic megafauna’ such as forest elephants(Loxodonta africana cyclotis), western lowlandgorillas ( Gorilla gom’lla gorilla), chimpanzees (Pantroglodytes), bongos ( Tregulaphus mryceros) andforest buffaloes (Syncerus cafer manus). | WWF & GTZ | Usongo, L., & Nkanje, B. T. (2004). Participatory approaches towards forest conservation: the case of Lobéké National Park, south east Cameroon. The International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 11(2), 119-127. |

| 28 | Wildlife co-management in the Bénoué National Park-Complex, Cameroon: A bumpy road to institutional development | Cameroon | 1993 | Cameroon lions, Elephants, spotted hyena, water buck, warthog | Ministry of Environment and Forests (MINEF) and a consortium of donors including the World Bank etc. | Mayaka, T. B. (2002). Wildlife co-management in the Bénoué National Park-Complex, Cameroon: A bumpy road to institutional development. World Development, 30(11), 2001-2016. |

| 29 | Local perceptions of Waza National Park, northern Cameroon | Cameroon | 1993 | antelope and monkeyspecies, giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), elephant (Loxodontaafricana), lion (Panthera leo), hyena (Crocuta crocuta) and adiverse avifauna (Tchamba & Elkan 1995; Scholte et al.1999b). | IUCN | Bauer, H. (2003). Local perceptions of Waza National Park, northern Cameroon. Environmental Conservation, 30(2), 175-181. |

| 30 | Understanding the Links Between Conservation and Development in the Bamenda Highlands, Cameroon | Cameroon | 1987 | The primate Preuss' Guenon,Coopers Mountain Squirrel | BirdLife International | Abbot, J. I., Thomas, D. H., Gardner, A. A., Neba, S. E., & Khen, M. W. (2001). Understanding the links between conservation and development in the Bamenda Highlands, Cameroon. World Development, 29(7), 1115-1136. |

| 31 | Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve | Central African Republic | 1990 | blue duiker Cephalophus monticola and the bay duiker Cephalopus dorsalis | Government | Noss, A. J. (1998). The impacts of BaAka net hunting on rainforest wildlife. Biological conservation, 86(2), 161-167. |

| 32 | Pendjari national park (PNP) in Benin | Benin | 1993 | Roan antelope, western hartebeest, western kob, buffalo | Government | Idrissou, L., van Paassen, A., Aarts, N., Vodouhè, S., & Leeuwis, C. (2013). Trust and hidden conflict in participatory natural resources management: The case of the Pendjari national park (PNP) in Benin. Forest Policy and Economics, 27, 65-74.Vodouhê, F. G., Coulibaly, O., Adégbidi, A., & Sinsin, B. (2010). Community perception of biodiversity conservation within protected areas in Benin. Forest Policy and Economics, 12(7), 505-512. |

| 33 | Case study on the Okavango Community Trust(OCT), Okavango Kopano Mokoro Community Trust(OKMC), and Khwai Development Trust(KDT) in Botswana | Botswana | 1997, 1998, and 1999 | Elephant, African Buffalo, Hippopotamus, Lechwe, Topi, Blue Wildebeest, Giraffe, Nile crocodile, Lion, Cheetah, Leopard, Sable Antelope, Black Rhinoceros, White Rhinoceros, | Government | Boggs, L. P. (2000). Community power, participation, conflict and development choice: Community wildlife conservation in the Okavango region of Northern Botswana. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.Mbaiwa, J. E. (2005). Wildlife resource utilisation at Moremi Game Reserve and Khwai community area in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Environmental Management, 77(2), 144-156. |

| 34 | Masoala National Park, Madagascar | Madagascar | 1993 | red-ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata rubra),Madagascar serpent eagle (Eutriorchis astur), Madagascar redowl (Tyto soumagnei), helmet vanga (Euryceros prevostii), leaftailedgecko (Uroplatus spp.) | Several NGOs | Ormsby, A., & Kaplin, B. A. (2005). A framework for understanding community resident perceptions of Masoala National Park, Madagascar. Environmental Conservation, 32(2), 156-164. |

| 35 | The dual nature of parks: attitudes of neighboring communities towards Kruger National Park, | South Africa | 2002 | lion, leopard, rhinoceros (both black and white Species), elephant, and Cape buffalo | Government | Anthony, B. (2007). The dual nature of parks: attitudes of neighbouring communities towards Kruger National Park, South Africa. Environmental Conservation, 34(3), 236-245.Carruthers, J. (1995). The Kruger National Park: a social and political history. University of Natal Press. |

| 36 | Conservation and development alliances with the Kayapó of south-eastern Amazonia, a tropical forest indigenous people | Brazil | 1992 | Tayassu pecari, Pteronura brasiliensis, Priodontes maximus, Panthera onca | Conservation International do Brasil (CI-Brasil) | Zimmerman, B., Peres, C. A., Malcolm, J. R., & Turner, T. (2001). Conservation and development alliances with the Kayapó of south-eastern Amazonia, a tropical forest indigenous people. Environmental Conservation, 28(1), 10-22. |

| 37 | Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park | Bhutan | 1993 | tigers(Panthera tigris), leopards (Panthera pardus), red panda (Alurusfulgens), gaur (Bos gaurus), golden langur (Presbytis geei) | Government | Wang, S. W., & Macdonald, D. W. (2006). Livestock predation by carnivores in Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan. Biological Conservation, 129(4), 558-565.Wang, S. W., Lassoie, J. P., & Curtis, P. D. (2006). Farmer attitudes towards conservation in Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan. Environmental Conservation, 33(2), 148-156. |

| 38 | A case study from the Saint Katherine Protectorate, Southern Sinai, Egypt | Egypt | 1996 | Sinai leopard, Nubian ibex, Dorcas gazelles | Global Environmental Facility (GEF) | Grainger, J. (2003). ‘People are living in the park'. Linking biodiversity conservation to community development in the Middle East region: a case study from the Saint Katherine Protectorate, Southern Sinai. Journal of arid environments, 54(1), 29-38. |

| 39 | A Case Study of Batang Ai National Park, Sarawak, Malaysia | Malaysia | 1991 | orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) | Government | Horowitz, L. S. (1998). Integrating indigenous resource management with wildlife conservation: a case study of Batang Ai National Park, Sarawak, Malaysia. Human Ecology, 26(3), 371-403. |

| 40 | Impacts of community-based conservation on localcommunities in the Annapurna Conservation Area,Nepal | Nepal | 1989 | Rhesus macaque,Himalayan Black bear, Barking deer, leopard and porcupine | KingMahendra Trust for Nature Conservation (KMTNC)--NGO | Bajracharya, S. B., Furley, P. A., & Newton, A. C. (2006). Impacts of community-based conservation on local communities in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Biodiversity & Conservation, 15(8), 2765-2786. |

| 41 | Kibale Association for Rural andEconomic Development(KAFRED) | Uganda | 1991 | variety of primates and birds | Government | Lepp, A. (2007). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tourism management, 28(3), 876-885. |

| 42 | Bwindi Impenetrable NationalPark | Uganda | 1991 | Mountain gorillas | Government | Hamilton, A., Cunningham, A., Byarugaba, D., & Kayanja, F. (2000). Conservation in a region of political instability: Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda. Conservation Biology, 14(6), 1722-1725. |

| 43 | Zones Cynégétiques Villageoises (ZCV) are community hunting reserves | Central African Republic | 1992 | Elephants, Old World monkeys, Patas monkey, Hominoidea | Government | Mbitikon, R. (2004). Village hunting zones: an experiment of community-based natural resource management in the Central African Republic. Game & Wildlife Science, 21(3), 217-226. |

| 44 | community basedwildlife hunting management of in the Gulzat Local ProtectedArea of northwest Mongolia | Mongolia | 2010 | Altai Argali | Government + WWF | https://www.iucn.org/downloads/iucn_informingdecisionsontrophyhuntingv1.pdf |

| 45 | Savé Valley Conservancy (SVC) | Zimbabwe | 1990 | elephants, rhinos, buffalo and lions | Government | Lindsey, P.A., et. al. 2008. Savé Valley Conservancy: a large scale African experiment in cooperative wildlife management. Pages 163-184 in B. Child, H. Suich and A. Spencely (eds.), Evolution and Innovation in Wildlife Conservation in Southern Africa, Earthscan, London, UK. |

| 46 | Bubye Valley Conservancy(BVC) | Zimbabwe | 1996 | Lions, African Elephants, African Buffalo, White Rhinos and, the third largest Black Rhino | Government | BVC. n.d. Bubye Valley Conservancy. Bubye Valley Conservancy, Zimbabwe.http://bubyevalleyconservancy.com |

| 47 | The Cawston Game Ranch in Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | 1990 | Plains Zebra, Giraffe, Tsessebe,Common Impala, Bushbuck, Red | Private | Lindsey, P. A., Alexander, R., Frank, L. G., Mathieson, A., & Romanach, S. S. (2006). Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife‐based land uses may not be viable. Animal Conservation, 9(3), 283-291. |

| 48 | Community‐based Natural Resource Management project in Kunene Region of Namibia | Namibia | 1994 | Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra, Black Rhino | Namibian NGO | Jones, B. T. (1999). Policy lessons from the evolution of a community‐based approach to wildlife management, Kunene Region, Namibia. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 11(2), 295-304. |

| 49 | Community based conservation of Markhor in Hazratishoh and Darvaz Ranges of Tajikistan | Tajikistan | 2004 | Markhor | Community based NGO | Alidodov, M., Amirov, Z., Oshurmamadov, N., Saidov, K., Bahriev, J. and Kholmatov, I. 2014.Survey of markhor at the Hazratishoh and Darvaz Ranges, Tajikistan. State Forestry Agencyunder the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe |

| 50 | Trophy hunting concessionsfor Argali and ibex in the Pamirs region in Tajikistan | Tajikistan | 2000 | SnowLeopard | NGO | Kachel, S.M. 2014. Evaluating the Efficacy of Wild Ungulate Trophy Hunting as a Tool for SnowLeopard Conservation in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan. A thesis submitted to the Facultyof the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masterof Science in Wildlife Ecology; 87 pp. |

| 51 | Community based trophy hunting in Tooshi-Shasha Conservancy in Pakistan | Pakistan | 1995 | Markhor | Government + WWF | Ali, H., Shafi, M. M., Khan, H., Shah, M., & Khan, M. (2018). Socio-economic benefits of community based trophy hunting programs. |

| 52 | Community based trophy hunting in Kaigah valley district Kohistan Pakistan | Pakistan | 2005 | Markhor | Government | Ghafoor, A. (2014). Sustainability of Markhor Trophy Hunting Programme in District Kohistan Pakistan (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Sains Malaysia). |

| 53 | Communal Forests Management Support Project in Benin | Benin | 2008 | Small antelopes and Small Game species. | African Development Fund | https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/Benin_-_Communal_Forests_Management_Support_Project_PAGEFCOM_-_Appraisal_Report.pdf. |

| 54 | Caprivi Communal Conservancy | Namibia | 1980 | Elephant, Black rhino, Giraffe, plains and mountain zebra, Kudu, | DFID | Bandyopadhyay, S., Guzman, J.C. & Lendelvo, S. (2010) Communal Conservancies and household welfare in Namibia. Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Windhoek, Namibia |

| 55 | Torra conservancy COmmunity based Natural resource Management | Namibia | 1998 | elephant, black rhino, lion, leopard, cheetah, hyaena, giraffe, mountain zebra, springbok, oryx and kudu | Government + NGO | Scanlon, L. J., & Kull, C. A. (2009). Untangling the links between wildlife benefits and community-based conservation at Torra Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 26(1), 75-93. |

| 56 | Conservation activities in Kaokoveld Namibia | Namibia | 1983 | elephant, black rhino, lion, leopard, cheetah, hyaena, | IRDNC - WWF | Holmes, T. (1992). Conservation activities in Kaokoveld (north-west Namibia). Biodiversity & Conservation, 1(3), 211-213. |

| 57 | Law, custom and community-based natural resourcemanagement in Kubulau District (Fiji) | Fiji | 2005 | Marine Animals and Terrestrial Animals | Government | Clarke, P., & Jupiter, S. D. (2010). Law, custom and community-based natural resource management in Kubulau District (Fiji). Environmental Conservation, 37(1), 98-106. |

| 58 | Indigenous Common Property Resource System In TheGuassa area of Menz | Ethiopia | 1975 | Ethiopian wolf(Canis simensis), | Government | Ashenafi, Z. T., & Leader-Williams, N. (2005). Indigenous common property resource management in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Human Ecology, 33(4), 539-563. |

| 59 | Annapurna Conservation Area (ACA) | Nepal | 1996 | Not specified | Government | Baral, N., & Stern, M. J. (2010). Looking back and looking ahead: local empowerment and governance in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 37(1), 54-63. |

| 60 | Communal Lands in Zambezi Valley of Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | 1991 | Guineafowl or Duike | Government | Byers, B. A., Cunliffe, R. N., & Hudak, A. T. (2001). Linking the conservation of culture and nature: a case study of sacred forests in Zimbabwe. Human Ecology, 29(2), 187-218. |

| 61 | A comparison of attitudes toward state-led conservation and community-based conservation in thevillage of Bigodi | Uganda | 1990 | Baboons, Buffalos and Elephants | Government | Lepp, A., & Holland, S. (2006). A comparison of attitudes toward state-led conservation and community-based conservation in the village of Bigodi, Uganda. Society and Natural Resources, 19(7), 609-623. |

| 62 | Western Community based Natural Resource Management in Ghats in southern India and Meghalaya state in north-eastern India, | India | 1980 | Actinodaphne lawsonii,Hopea ponga, Madhuca | Not specified | Ormsby, A. A., & Bhagwat, S. A. (2010). Sacred forests of India: a strong tradition of community-based natural resource management. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 320-326. |

| 63 | Community-based natural resource managementPractice in the Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia( Phnom Samkos WildlifeSanctuary (PSWS)) | Combodia | 2000 | Wild Animal(not specified | INGO | CASCIO, A. L., & Beilin, R. (2010). Of biodiversity and boundaries: a case study of community-based natural resource management practice in the Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 347-355. |

| 64 | Communal and freehold rangelands inthe Waterberg region of north-central Namibia | Namibia | 2000 | Oryx gazelle, elandTaurotragus oryx and | No specified | Kauffman, M. J., Sanjayan, M., Lowenstein, J., Nelson, A., Jeo, R. M., & Crooks, K. R. (2007). Remote camera-trap methods and analyses reveal impacts of rangeland management on Namibian carnivore communities. Oryx, 41(1), 70-78. |

| 65 | Community natural resource management: thecase of woodlots in Northern Ethiopia | Ethiopia | 1991 | No specified | Government | Gebremedhin, B., Pender, J., & Tesfay, G. (2003). Community natural resource management: the case of woodlots in northern Ethiopia. Environment and Development Economics, 8(1), 129-148. |

| 66 | Community-based natural resource management and power in Mohammed Nagar village, Andhra Pradesh, India | India | 1990 | No specified | Government | Saito-Jensen, M., Nathan, I., & Treue, T. (2010). Beyond elite capture? Community-based natural resource management and power in Mohammed Nagar village, Andhra Pradesh, India. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 327-335. |

| 67 | Sankuyo TshwaraganoManage ment Trust (STMT | Botswana | 1995 | Oryx gazelle, elandTaurotragus oryx and | NGO | Barnett, R., & Patterson, C. (2006). Sport hunting in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region: an overview. TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. |

| 68 | Khwai Development Trust (KDT) | Botswana | 2000 | Oryx gazelle, elandTaurotragus oryx and | NGO | Barnett, R., & Patterson, C. (2006). Sport hunting in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region: an overview. TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. |

| 69 | Nqwaa KhobeeXeya Trust (NKXT) | Botswana | 1998 | Oryx gazelle, elandTaurotragus oryx and | NGO | Barnett, R., & Patterson, C. (2006). Sport hunting in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region: an overview. TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. |

| 70 | A case study ofTrophy hunting in western china | China | 1997 | Argali Ovis ammon | Government | Harris, R. B., & Pletscher, D. H. (2002). Incentives toward conservation of argali Ovis ammon: a case study of trophy hunting in western China. Oryx, 36(4), 373-381. |

| 71 | Mitigation of negative human impacts on large carnivore populations in Niassa National Reserve, northern Mozambique | Mozambique | 2003 | Lion, Leopard, Spotted Hyaena And African Wild Dog | NGO | Begg, C., & Begg, K. (2009). Niassa carnivore project. Produced for SRN, Maputo. |

| 72 | Kayapo Indigenous Area | Brazil | 1990 | Geochelone tortoises, A’Ukre | Government | Peres, C. A., & Nascimento, H. S. (2006). Impact of game hunting by the Kayapó of south-eastern Amazonia: implications for wildlife conservation in tropical forest indigenous reserves. Biodiversity & Conservation, 15(8), 2627-2653. |

| 73 | Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan | Bhutan | 1996 | Leopard, tiger, Himalayan black bear, dhole | Government | Wang, S. W., & Macdonald, D. W. (2006). Livestock predation by carnivores in Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan. Biological Conservation, 129(4), 558-565. |

| 74 | Lobeke National Park | Camaroon | 1975 | Elephants, Buffellos, and low land Gorillas | WWF | Usongo, L., & Nkanje, B. T. (2004). Participatory approaches towards forest conservation: the case of Lobéké National Park, south east Cameroon. The International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 11(2), 119-127. |

| 75 | Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve | China | 1961 | Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus), Indo-Chinese tiger (Panthera tigris), gaur | Government, UNESCO | Albers, H. J., & Grinspoon, E. (1997). A comparison of the enforcement of access restrictions between Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve (China) and Khao Yai National Park (Thailand). Environmental Conservation, 24(4), 351-362. |

| 76 | St Katherine Protectorate | Egypt | 1990 | Red fox, Sinai leopard, Nubian ibex | Government | Grainger, J. (2003). ‘People are living in the park'. Linking biodiversity conservation to community development in the Middle East region: a case study from the Saint Katherine Protectorate, Southern Sinai. Journal of arid environments, 54(1), 29-38. |

| 77 | Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve | India | 1990 | snow leopard (Panthera uncia), brown bear (Ursus arctosisbellinus | Government | Maikhuri, R. K., Nautiyal, S., Rao, K. S., & Saxena, K. G. (2001). Conservation policy–people conflicts: a case study from Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve (a world heritage site), India. Forest Policy and Economics, 2(3-4), 355-365. |

| 78 | Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve | India | 2000 | Tiger (Panthera tigris), the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Government | Arjunan, M., Holmes, C., Puyravaud, J. P., & Davidar, P. (2006). Do developmental initiatives influence local attitudes toward conservation? A case study from the Kalakad–Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, India. Journal of environmental management, 79(2), 188-197. |

| 79 | Gir National Park | India | 1992 | Asiatic Lions | GEF | Mukherjee, A., & Borad, C. K. (2004). Integrated approach towards conservation of Gir National Park: the last refuge of Asiatic Lions, India. Biodiversity & Conservation, 13(11), 2165-2182. |

| 80 | Annapurna Conservation Area | Nepal | 1993 | Mountain Tigers | Government | Bajracharya, S. B., Furley, P. A., & Newton, A. C. (2006). Impacts of community-based conservation on local communities in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Biodiversity & Conservation, 15(8), 2765-2786. |

We identify major elements and relationships that are important for analyzing and framing CBTH arrangements. We then adopt the model of collaborative governance by Ansell and Gash (2008) to make precise assumptions about variables and parameters that enable us to predict the outcomes of CBTH programs.

Core Components of Collaborative Governance For CBTHStarting Conditions of CBTH ProgramsAnsell and Gash (2008) argue that incentives of stakeholders to participate in collaborative governance hinge upon power (and resource) balance and certain level of trust among participants as initial background conditions at the outset of collaborative governance (See Fig. 1). Power of stakeholders manifests in terms of status, organizational infrastructure for representation (English, 2000), financial or human resources with government, skills and expertise of the local people to engage in discussions about highly technical problem, and the time, energy, or liberty to engage in time-intensive collaborative processes (Yaffee & Wondolleck, 2003). Power imbalance, or the prehistory of antagonism among stakeholders is likely to express itself in the form of distrust, strategies of manipulation, and dishonest communications, and lessening the incentive to participate (Ansell & Gash, 2008; Schuckman, 2001; Warner, 2006). Thus, they posit that strategies of empowerment and representation of weaker stakeholders or/and steps to remediate the low levels of trust among the stakeholders should be taken to initiate collaborative governance effectively (Ansell & Gash, 2008).

Also, the incentive to participate in collaborative governance depends partly upon expectations of stakeholders about concrete, tangible, effectual policy outcomes or benefits against the balance of time and energy that collaboration requires (Brown, 2002; IUCN, 2012; Naidoo et al., 2011) and lack of alternative means through which stakeholders can achieve their interests unilaterally (W. B. Adams, 2013; Balint & Mashinya, 2006; Bouwen & Taillieu, 2004). Thus, four factors may interplay to affect the incentives to participate in collaborative governance in general: interdependence of stakeholders, power imbalance, prehistory of antagonism (level of distrust) and potential tangible benefits.

When it comes to conservation of wildlife through CBTH in developing countries, those four background factors may also work to affect the incentives to participate in CBTH. For CBTH to be considered by government as an alternative mechanism to conventional top-down, command-and-control conservation policy and proposed to local communities, interdependence between government and local communities should exit. In other words, government may have an incentive to capitalize on energy, ideal, and effort of local communities to conserve endangered wildlife and propose CBTH to local communities in the first place. Such incentive might come from the realization that previous government policies have failed to achieve conservation of wildlife, often with the help or advice of international conservation organizations (Khan, 2012).

Failure of community-based conservation programs in many cases often has something to do with the third factor, the prehistory of conflict between strong governments and relatively weak local communities that may limit participation in collaboration in general. Conventional conservation policies, such as establishing national parks as protected areas, often lead to conflicts between government and local communities by restricting local communities from using natural resources including wildlife in protected areas and even displacing them forcibly out of the protected areas (Biggs et al., 2017; Frost & Bond, 2008; Mombeshora & Le Bel, 2009; Ribot, 2002).

Economically poor local communities who live on subsistence agriculture in their traditional lands perceive wildlife mainly as a threat to their livelihoods (Dickman, 2010). For example, in Uganda, stampedes of active wildlife animals on farmlands at the edge of the Kibale National Park reduced crop production dramatically (Naughton-Treves, 1997). Thus, they tend to poach wild animals illegally and harm their habitats for their survival and are often tempted to illegal wild animals trafficking for economic reason, which have limited the effectiveness of conservation policy (Jachmann, 2008; Treves & Karanth, 2003). In Mozambique, the colonial rules prevented local communities in reserved forests from using natural resources, consequently local communities were united against the government and consumed all the local forest resources (Virtanen, 2005).

Despite the uncertainty of effectiveness of community-based conservation from the beginning, government cannot but rely upon bottom-up approach that utilize the effort of local communities in conserving wildlife instead of ineffective command-and-control policies. In Pakistan’s mountain regions of Karakoram, Hindukush and the Himalayas, protected Areas, usually established by the state, created conflicts with local livelihoods (Khan, 2012; Shackleton, 2001; Virk et al., 2003). Similarly, in Namibia, after the establishment of protected areas, Herero communities were disconnected from their lands and associated resources (A. F. Hoole, 2010).

Taking these dynamics into consideration, the first contingency proposition is proposed as follows:

- (1)

If government realizes the failure of conventional conservation policies, then it is more likely to consider and propose CBTH to local communities.

The dependency of local communities on CBTH may come from power imbalances between strong government and weak local communities who neighbor or live closely with wildlife animals (Bouwen & Taillieu, 2004; Seixas & Berkes, 2010; Twyman, 2000). Considering economic survival and rights to use natural resources independently as the main interests of economically poor and politically weak local communities, the expectations to reap tangible benefits from collaboration in CBTH may affect strongly the incentive to participate in collaboration.

CBTH programs are based on the premise of financial incentives from regulated hunting of wildlife for local communities who are committed to conserve those animals (W. M. Adams & Hulme, 2001; Mayaka et al., 2005; Taylor, 2009; Virk et al., 2003; Wijnstekers, 2011). The expectations of direct benefits such as hunting and indirect benefits such as ecotourism for the local people can make them interested in being engaged in CBTH programs. Studies have shown high motivation and interest in participation in community-based conservation programs in general where potential for these incentives is relatively high (Frost & Bond, 2008; IUCN, 2012; Khan, 2012). CBTH is likely to be more attractive to local communities who live in remote and inaccessible or politically unstable areas where alternative ways to make revenue, such as photographic ecotourism, may not be viable. According to Lindsey et al. (2007), trophy hunting has several advantages over photographic tourism in areas where infrastructure is not available, weather is not friendly for large public to visit, or high density of viewable wildlife is not available. Also, hunting industry is relatively more resilient to political instability than usual tourism (Damm, 2008).

Thus, the second contingency proposition is:

- (2)

Despite the prehistory of conflicts and power imbalance as usual background conditions in many developing countries, if local communities perceive the possibility to acquire necessary rights to manage their natural resources as well as potential economic benefits from trophy hunting, they are more likely to come to the table for collaboration with the government.

One interesting case that may test the first and second propositions is observed in Zimbabwe (Baker, 1997). When the establishment of ‘Gonarezhou National Park’ had evicted the local community called “the Shangaan” from their traditional lands in the 1960s did not bear fruit of conserving wildlife, the government suggested community-based conservation that would give the Shangaan people responsibility for wildlife conservation in their areas. However, the Shangaan community did not collaborate with the government’s proposal due to lack of trust on the government and hence increased poaching in and around the park. In the early 1980s, the Shangaan agreed to work with government on the condition that the community would have the authority to manage wildlife in their areas and they would derive economic returns from safari hunting. Since the community started selling the right to kill two elephants for 3,000 USD over a 5 years period, the community could build a school, a grinding mill, and a clinic with the revenues from regulated hunting. With the tangible economic benefits from Safari hunting, the community’s attitude towards wildlife animals changed dramatically enough to protect them as a valuable community asset (Andrade & Rhodes, 2012; Balint & Mashinya, 2006). Also, in Northern Pakistan, local communities who experienced conflicts with the government due to protected area policy, later participated in CBTH with their expectation of potential economic incentives (80% of the hunting revenues) from trophy hunting (Khan, 2012).

However, mere participation of local communities in initiating CBTH does not always guarantee successful outcomes in the end. Sneaky and pervasive power imbalances or lack of trust due to previous conflicts may lurk and prevent collaboration even after stakeholders start CBTH. Thus, one needs to understand how internal process of CBTH deals with those problems of power imbalance, lack of trust, and poor governance. For example, in Kilosa district in Tanzania where two groups of communities experienced conflicts in competition for scarce resources, the government established Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) in 1998 aimed at wildlife conservation and rural development at the same time. Although local community representatives actively participated in decision-making process from the beginning, however, during the implementation, conflicts occurred and were intensified further that caused the projects to fail in the end (Nilsen, 2009).

Facilitative LeadershipIn order for successful collaboration from the start of negotiation to structure process to the achievement of ultimate outcome, there should be actors with leadership ability of bringing broad range stakeholders to one platform, engaging them with collaborative spirit, setting clear ground rules, building trust, facilitating dialogue, exploring creative solutions for common goals, maintaining technical credibility, empowering weaker stakeholders, and ensuring the integrity of collaborative process (Ansell & Gash, 2008; Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Lasker et al., 2001; Yaffee & Wondolleck, 2003). In those contexts where power imbalances exist among stakeholders who distrust each other, leadership becomes more critical (Ansell & Gash, 2008). Also, scholars overwhelmingly argue that leadership should be facilitative rather than authoritative (Bouwen & Taillieu, 2004; Kaner, 2014; Nalbandian, 1999; Ozawa, 1993). Ansell and Gash (2008) propose that the types of facilitative leader may hinge upon the context of power distribution and incentive to participate. The third-party actors whom stakeholders acknowledge and trust, may provide neutral and facilitative services in high-conflict and low-trust situations, where power is balanced with stakeholders’ willingness to participate. However, contexts where power imbalances exist or incentives to participate are weak may require strong “organic” leaders who may belong to community and can gain trust of various stakeholders at the start of the negotiation process. Thus, availability of such organic leaders might seriously limit the effectiveness of collaborative process (Ansell & Gash, 2008).

Literature on community-based conservation also finds facilitative leadership crucial for the success of CBTH programs (Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; German & Keeler, 2009; Jachmann, 2008; Paudyal et al., 2017; Shackleton, 2001). Considering the general context of endangered species management in developing countries, such as prehistory of conflict and lack of trust, and building upon the second proposition in the previous section, facilitative third party actors, such as local and international conservation NGOs may be very helpful even in the presence of power imbalance.

For CBTH to be initiated, there should be some actors who can help stakeholders to link social involvement and development with conservation objectives. Local, or international conservation NGOs can be instrumental in orchestrating relevant actors to buy that idea (Cash & Moser, 2000; Folke et al., 2005). For example, in Namibia, Garth Owen-Smith and Margaret Jacobsohn as leaders pioneered the community-based conservation program called ‘the Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC)’ where they worked with local community, called ‘Herero,’ in order to link social and economic development to the conservation of region’s wildlife and other natural resources (A. F. Hoole, 2010). The program was quite successful in controlling rampant illegal hunting of black rhinos and elephants and increasing most wild species with major contributions from community-appointed game guards in the northeast of Namibia (Roe et al., 2000). IRDNC’s leadership was facilitative in fact-finding by engaging the Namibian government in conducting community surveys and setting up community game guard program. In Belize, a leader of NGO was instrumental in creating the Port Honduras Marine Reserve by persuading the Belize Government and surrounding communities to adopt the Reserve and by linking international concerns on marine ecosystems with local economic needs (Fernandes, 2005; Seixas & Berkes, 2010). Also, in the Guyana’s Community-based Arapaima Conservation, a local NGO played a role in finding funding for the project, establishing links between local community and government authorities, and building their capacities (Fernandes, 2004). Also, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) played critical roles as a facilitator for conservation program in Northern Pakistan in educating local people, providing technical training for community wildlife guards and government field officers, creating an environment for mutual trust and commitment between the government agencies and community, and safeguarding the whole process (Khan, 2012; Mir, 2006; Zafar et al., 2014).

Leadership may come from community side (Folke et al., 2005; A. F. Hoole, 2010; McIntosh & Renard, 2010) as well as government side (Balint & Mashinya, 2006). Once a community decides to participate in CBNRM or CBTH, ‘organic’ leadership of community representative becomes very important in informing community members about potential economic benefits from their own conservation efforts, and sharing their own knowledge with government and international organizations (Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Folke et al., 2005; Seixas & Berkes, 2010). In CBTH, community leaders may lead the process of surveying wildlife, deciding on quotas, monitoring illegal activities and poaching, and imposing penalties on community members who violate the rules (Taylor, 2009). Leadership roles of government officials in CBTH and CBNRM are also important in showing stable and transparent commitment during collaboration process since abrupt change in government leadership often leads to the failure of the project. For example, in the CAMPFIRE program in Zimbabwe, community members lost their trust in the government after change of leadership in the government designated committee caused malpractices in the distribution of revenues of trophy hunting (Balint & Mashinya, 2006).

In view of the evidence of factors of facilitative leadership affecting CBTH, the third and fourth contingency propositions are formulated as bellows:

- (3)

Even if there is a prehistory of conflict, lack of trust, and power imbalance between community and government, facilitative third parties, such as local or international conservation NGOs can play critical roles in initiating and maintaining CBTH.

- (4)

If “organic” leadership from community is instrumental in implementing conservation efforts as CBTH programs indicate, and government leadership provides stable and transparent commitments during the process, CBTH will be more likely to succeed.

Institutional design in the model of collaborative governance refers to the basic protocols and ground rules for collaboration that are designed to secure the procedural legitimacy of the collaborative process (Ansell & Gash, 2008). Literature on community-based conservation programs suggests several design features for successful collaboration that include open and inclusive representation of important stakeholders (Bouwen & Taillieu, 2004; Mayaka et al., 2005; Newig & Fritsch, 2009), clear ground rules (Usongo & Nkanje, 2004), process transparency (Brunet & Aubry, 2016; Dudley, 2008), clear definition of roles (Baldus, 2009; Taylor, 2009), formalization of governance structures (Di Minin et al., 2016; Hayes, 2006), consensus-oriented decision-making and the use of realistic deadlines (W. B. Adams, 2013; Ansell & Gash, 2008). Exclusion of important stakeholders undermines the legitimacy of collaborative outcomes (Ansell & Gash, 2008). Clear ground rules work to reassure stakeholders, who may have skeptical frame of mind and be sensitive to issues of equity and power imbalance, that process is fair, open, and transparent. Formal acknowledgment of transparent governance structure helps stakeholders to feel confident that the public negotiation is real rather than window dressing.

For sustainable management of common pool resources, Ostrom (2008) suggests critical principles of a governing institution that resemble some of the institutional design of collaborative governance. For example, the governing institution should define clear group boundaries, ensure that community gets the right to participate in rulemaking, and make sure that community has the right to modify these rules in case they affect the interests of local community (Ostrom, 2008; Schumann, 2001). Identification of the affected community in local natural resource management is often made on the criteria of geographical proximity to the resource (B. Adams, 2008; Lebel et al., 2008). However, the number and the scope of stakeholders in wildlife conservation are often larger since some wild animals’ habitats go beyond conserved areas (Child, 2013; Pietersen, 2011). Thus, representation of stakeholders in collaborative governance in wildlife conservation, such as CBTH, needs to be flexible and adaptable enough to accommodate both complex and diverse stakeholder interests.

The success of community-based conservation initiatives highly depends on the nature(inclusiveness) of the basic rules and protocols that provide procedural legitimacy and govern the whole process smoothly (Aheto et al., 2016; Baker, 1997; Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Chabwela & Haller, 2010; IUCN, 2012; Khan, 2012; Nagendra & Ostrom, 2012; NASCO, 2010; Newig & Fritsch, 2009; Ostrom, 2009). These basic rules and protocols are collectively referred to institutional designs that allow (or obstruct) the inclusion of certain members of community through certain rules.

An inclusive institutional design ensures the opportunity for each stakeholder to deliberate with others about setting objectives for achieving policy outcomes through consensus (A. Hoole & Berkes, 2010; Mir, 2006; Shackleton, 2001). In such deliberative designs, there are more chances that indigenous knowledge and skills are incorporated which increases shared understanding of each stakeholder on the common good use (Natcher & Hickey, 2002; Redpath et al., 2013; Seixas & Berkes, 2010). Also, non-inclusive representation of one or many stakeholders might lead to vicious cycle by increasing the power imbalance and knowledge gap (Aheto et al., 2016). Hence, an inclusive institutional design should fulfill at least two important requirements. First, it must allow local people to possess property rights of resource use; secondly, it should enable local people to construct local level institutions that control the use of the resource, distribution of benefits and redressal of complaints arising during the use of the resources etc. In a study of five forests in Uganda, Banana and Gombya-Ssembajjwe (2000) find the condition of forests better in areas where property rights are well known and enforced than in those areas where national laws lack enforcement.

We thus argue that if explicit rules are in place which guide the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder in a way that is inclusive and does not discriminate (or exclude) one stakeholder, then participatory process of the CBTH will be more sustainable in terms of participation and outcomes.

We thus present the following proposition:

- (5)

If the existing institutional structure allows the creation of ground rules and basic protocols for collaboration that is inclusive and open to change, the CBTH is likely to be sustainable.

Existence of clearly defined laws, regulations and procedures developed with local community inputs and which are periodically reviewed and updated, can influence the success of CBTH programs. The key principles for successful CBTH programs as suggested by IUCN include a transparent government framework characterized by clear allocation of responsibilities, accounting for revenues in a transparent manner and distribution as per agreements, taking steps to eliminate corruption and ensuring compliance with all national and international requirements and regulations by relevant bodies such as administrators, regulators and hunters (IUCN, 2012). A case study by Gibson and Becker (2000) reflects a strong local community in Western Ecuador which failed to protect its forest and wild animals from illegal hunting despite the positive valuation of the tropical forests and secured property rights and a rich history of (other) micro-institutions. The same study finds that rules have had a direct impact on the condition of forest degradation and its related resources such as wildlife.

Whether CBTH programs result into successful outcomes depends on the way in which conflicts and deadlocks among the stakeholders are resolved. We find a considerable number of cases where conflicting opinions have reduced commitment and hindered the implementation of community-based conservation programs (Nagendra & Ostrom, 2012; Redpath et al., 2013; Schumann, 2001; Taylor, 2009). A detailed study enlisting numerous failure cases by Chabwela and Haller (2010) indicates that conflicts between authorities and the local people over wildlife resource use have exacerbated the differences and resulted into failure. Studies also show a strong influence of economic incentives on conflict resolution in community-based conservation programs. In Northern Pakistan, where perceived inadequate opportunities for income generation was observed as a main reason for lack of participation in environmental protection, local people were ready to conserve environment on the condition of incentives provision

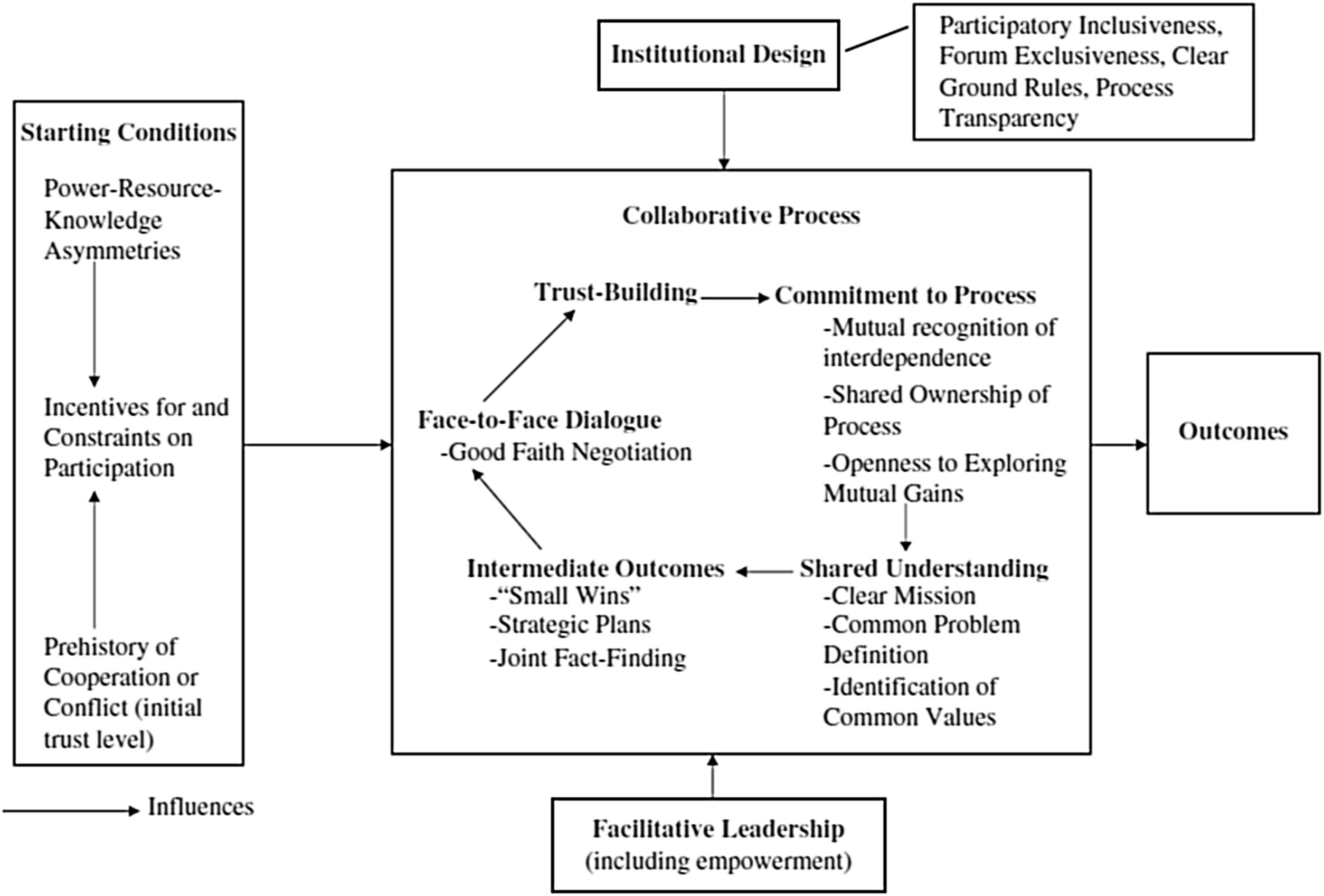

Collaborative ProcessThe community-based trophy hunting is a collaborative process that evolves in multiple inter-dependent stages (W. M. Adams & Hulme, 2001; IUCN, 2012; Khan, 2012; Krug, 2001; Lebel et al., 2008; Mayaka et al., 2005; Paudyal et al., 2017; Taylor, 2009). These stages can be further classified into distinct steps which are generic in nature but each of them is specific to different circumstances depending on the nature of the case. In Fig. 2, we explain the components of CBTH in line with the Ansell and Gash (2008) model.

Face-to-Face Dialogue among stakeholdersAll collaborative governance types require face-to-face dialogue among stakeholders. However, Ansell and Gash (2008) argue that face-to-face dialogue itself does not always lead to collaboration. It can reinforce stereotypes or increase antagonism. In most of the community-based conservation programs, face-to-face communication and dialogue between the local people, government authorities and the private partners plays significantly important role, however, it does not necessarily guarantee successful conservation outcomes (Balint & Mashinya, 2006; Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Damm, 2008; Frost & Bond, 2008; German & Keeler, 2009; Lindsey et al., 2007; Newig & Fritsch, 2009; Ostrom, 2008). Since differences of opinions and perception about the ways in which conservation and development strategies are formulated and adopted exist in common pool related problem, sitting together around one table increases the chances of consensus (Khan, 2012). Although not sufficient condition, face-to-face dialogue improves better communication and decision-making environment between government authorities, local community representatives in contexts where the prehistory is dominated by conflicts (Ansell & Gash, 2008; Ostrom, 2008). According to Frost and Bond (2008), participation and the sense of ownership of marginal groups within community was highly enhanced when face-to-face dialogue and discussions held at multiple decision-making occasions. Not only mere participation, studies also show discussion with local people and their representatives helps build confidence and skills which are critical for the success of the negotiation process. However, the success of such discussion again depends on the available leadership as well as commitment to the process which are equally important for the collaborative process.

The decline of a promising CBNRM in Mahenye, Zimbabwe reflects huge gap in direct communication between the local people and the committee chiefs who were undemocratically imposed on them (Balint & Mashinya, 2006). This gap consequently resulted into the breaking of participatory system which was crucial for the success of conservation program. Another study on participatory collective action in the Kafue Flats, Zambia shows the local institutions regulating the common good were strengthened through discussion among local stakeholders (Chabwela & Haller, 2010). The basic idea of such discussion is to empower those who perceive limited role in decision making despite having differences of opinion about the mechanism.

While, literature on failed community conservation projects frequently attributes lack of communication as the main factor that reduces confidence, successful projects clearly indicate the role of open dialogue and communication (Balint & Mashinya, 2006; Chabwela & Haller, 2010). For example, despite local people were not even aware of their rights, and had little confidence in the government, sitting around the same table with district authorities highly contributed in overcoming the communication barrier between the government and local people in Northern Pakistan (Khan, 2012).

As an important step towards sustainable collaboration, we present the following proposition:

- (6)

Coupled with other parallel measures, such as government service delivery and economic incentives etc., face-to-face meetings of the local community representatives with government officials or private partner will positively influence the performance of CBTH.

The degree of stakeholders’ commitment to the collaborative process can influence the CBTH through mutual recognition and joint appreciation. In many cases in developing countries, CBTH or CBNRM starts with the funding from international organizations through a formal proposal. In some cases, such as the Northern Pakistan, the role of local people in formulating the contents of CBTH from the beginning is limited due to requirement of funding proposals. Despite such limitations, local people might still agree on some bounded objects of negotiation. These include commitment of delivery of revenues (or benefits) from trophy hunting to the community welfare, participation in the implementation mechanism specially when there is employment opportunities, and government capacity and performance.

In Northern Pakistan case, the IUCN and Agha Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP) suggested to the government the feasibility of a community-based natural resource management. Later, after the proposal for project funding submitted by IUCN to Global Environmental Facility (GEF) through United Nations Development Program (UNDP) got accepted, the local people were invited to the negotiation process where they cooperated in designing the ground rules for setting up objectives of collaboration (GEF, 2006). Analysis of the project documents reveals a well-designed framework that gives more control to local people and empower their capacity to conserve natural resource, while equally showing strong commitment on the continuity of the project. Other studies point to the weak commitment by the central government agencies in continuing the CBTH process as a problem (Balint & Mashinya, 2006).

Commitment however depends on existing trust among stakeholders and transparency in procedures that establish the integrity for negotiation. Initiatives that seek increasing involvement of local communities can create a sense of commitment and ownership among local people that in turn overcome any power imbalances or differences of perceptions (Andrade & Rhodes, 2012). Ansell and Gash (2008) argue that despite a collaborative governance is mandated, lack of incentive to participate might be translated as lack of real commitment on the part of stakeholders. In the context of CBTH, several studies consider sustained commitment among stakeholders towards effective implementation of conservation plans as an important part of the collaborative process (W. B. Adams, 2013; Frost & Bond, 2008; Nagendra & Ostrom, 2012; Wijnstekers, 2011). Our analysis of relevant CBTH cases suggest that community’s belief about government commitments to ensure equitable implementation always matter. For example, in one case, two-third of those who knew that the government has passed a new land law, doubted the government’s commitment in ensuring its equitable implementation (Soto et al., 2001). Although the consensus-oriented governance greatly reduces the risks so that stakeholders can make more commitment, the CBTH still needs willingness to accept the outcomes of deliberation, even if they do not go in line with stakeholder’s full interest.

- (7)

A strong commitment demonstrated by stakeholders specially governments and NGOs can win the cooperation of local community despite any limitation during the initiation of the CBTH.

We note multiple cases of CBTH programs where uncertain behavior of government authorities and lack of decision making capacity related to community based conservation influence the morale of community participation that ultimately lead to failure in conservation (Balint & Mashinya, 2006; German & Keeler, 2009; A. F. Hoole, 2010; Khan, 2012). For example, one conservation study highlights lack of clarity on key decisions among local officials which resulted into severe limits on benefits to local communities and effectively lessened their role in governance (A. Hoole & Berkes, 2010). In a case study of Central Karakoram National Park Pakistan, one view is quoted as: “We are ready to manage the pastures to conserve them but we wouldn’t like the government to tell us that we have no use rights in the Park” (Imran et al., 2014)[P.296]. CBTH does not necessarily means that the community has been given full decision-making power. For example, some community members still perceive that decision-making powers (other than fund distribution) lie with government-controlled departments. CBTH programs have been frequently halted due to situations where government agency does not have the capacity (e.g knowledge, training etc), organization(e.g. skilled human resource), status(e.g. legislation), or resources to participate(e.g to initially finance the project), or to participate on an equal footing with other stakeholders (Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Folke et al., 2005).

Shared UnderstandingAnsell and Gash (2008) argue that shared understanding about collective achievement is crated at some point during collaboration. This might happen in some CBTH cases, where community is engaged from the beginning. However, in general, CBTH programs vary in the level of understanding between community and government or NGOs. Initially, local community perceives the outcome of collaboration as economic incentive and livelihood given the socio-economic conditions of the society and their attachment to natural resource. At the same time, intervening organization or governments’ aims differ as their primary objective is environmental conservation. A recent study undertaken in Central Karakoram National Park, Pakistan by Imran et al. (2014) examined the differences in opinions about environmental objectives among four stakeholders associated with protected area. The study finds opinions of the stakeholders towards environmental objectives closely linked to their incentives. This indicates that despite differences in opinions, local community might develop understanding with government and international organizations if they agree on collective actions that embody incentives for local community. Several factors might influence local community perception about the natural resource conservation. These include, the history of conservation in the area, awareness of community about environmental concerns and benefits to the local community (Ormsby & Kaplin, 2005). Moreover, effective communication among stakeholders may help in developing shared understanding among stakeholders.

Intermediate OutcomesConcrete, intermediate, “small wins” from collaboration represent not only tangible outputs, but also critical process outcomes that can feed back into a virtuous collaborative circle of trust building and commitment (Ansell & Gash, 2008). Intermediate outcomes may not be helpful for trust building where stakeholders have more ambitious goals that cannot easily be parsed into small wins (Vangen & Huxham, 2003). Ansell and Gash (2008) even posit that a collaborative path should not be pursued by stakeholders when prior antagonism between stakeholders is high that requires long-term commitment to trust building and small wins are not expected. Intermediate outcomes in CBTH cases include local-level development or conservation plans or spending of initial external funding on conservation related expenditures (Bunge-Vivier & Martínez-Ballesté, 2017; Shackleton, 2001; Wijnstekers, 2011). Continuity in these small wins are crucial for long term sustainability of the CBTH process. For example, in Northern Pakistan, the community as well as government anticipated intermediate wins, such as the successful distribution of trophy revenue through village development plan and establishment of local monitoring team which looked after the animals (Khan, 2012). This crucially increased the long-term commitment and cooperation among stakeholders. Despite conservation being main objective of IUCN, showing positive performance on small wins was necessary for long term success.

We thus suggest that:

- (8)

Intermediate outcomes that create short-term tangible gains (for community) are crucial for building a momentum that can lead to successful CBTH process.

The governance structure of CBTH programs can be framed as a form of collaborative governance that involves multiple stakeholders in the management of common pool resources. By referring to Ansell and Gash(2008)’s collaborative governance framework and conducting detailed review on 80 published case studies about CBC and CBTH, we develop a collaborative governance framework and eight contingency propositions that enable practitioners and researchers to better understand, design, and implement CBTH programs.

Regarding the initial conditions to engender CBTH in developing countries, we propose that the failure of conventional top-down conservation policies, perception of local communities about potential benefits from CBTH, and existence of facilitative leadership, such as local or international conservation NGOs will play critical roles in initiating CBTH, even under the prehistory of conflict, power imbalance, and lack of trust.

We also propose organic and instrumental leadership from community and government and inclusive design that creates ground rules and basic protocols are important outside factors to induce stable and strong commitment from participants during the collaboration process. Inside collaborative process, constructive, trust-building face-to-face meetings and generation of intermediate outcomes are identified as crucial factors in building a momentum for successful CBTH outcomes.

As a collaborative governance, successful CBTH may need to satisfy almost every factor of Ansell and Gash’s model. However, we try to adjust the model tailored to CBTH with various case studies in many different parts of the world. Still, in order to generalize our model, more in-depth single case studies or comparative case studies should be conducted by future researchers to test our propositions.

Declaration of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.