Marine Seismic Surveys are an important source of concern for marine biodiversity conservation worldwide. In Brazil, Environmental Federal Agency IBAMA has developed a considerably advanced mitigation/monitoring requirements package in 18 years of environmental licensing practice, with standardized guidelines since 2005. Adding to global efforts aiming at filling knowledge gaps over the impacts on biodiversity, IBAMA has been able to foster important marine research through environmental licensing requirements. Better communication of research findings to the international scientific community remains a challenge to be addressed. Nevertheless, current institutional and legal reforming initiatives jeopardize the evolution of environmental control of Marine Seismic Surveys in Brazil.

In the last decades, the marine scientific community has developed an increasing concern over the anthropogenic noise intensification in the oceans as an important threat to biodiversity and animal welfare (e.g., Cummings and Brandon, 2004; IWC SC, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017; Popper and Hawkins, 2016, 2012; Simmonds et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015). Very far from Jacques Cousteau's ‘Silent World’, our oceans are a realm of sound – which travels far better underwater than light does. In the oceans, underwater sound becomes a critical resource for marine fauna communication, orientation and overall spatial perception (Jasny et al., 2005; Simmonds et al., 2004). The main anthropogenic sources of noise are related to shipping, oil and gas exploration and production, naval sonar, military operations, fishing and research (Harris et al., 2017; Hildebrand, 2009). Among these activities, Marine Seismic Surveys (MSS) are often cited as one of the largest contributors to this scenario.

Marine Seismic Surveys are a widespread method used in the offshore petroleum industry to locate potential areas of exploratory interest. The seismic techniques use sound to probe the Earth and help geophysicists develop geological models of the sedimentary basins. In marine exploratory surveys, underwater sound generation is generally accomplished through a quick release of pressurized air from metal cylinders known as airguns (Dragoset, 2000). Seismic specialized vessels tow arrays of airguns that fire simultaneously in regular intervals (10–15s) to produce high-intensity sound pulses that propagate down the seabed (Caldwell and Dragoset, 2000) and interact with the different geological layers. The reflecting echoes are captured by towed hydrophone arrays and processed to form the underground images that are used to guide the planning of wells drilling.

While there are still significant knowledge gaps on the impacts seismic surveys can have upon marine life, there is a growing body of literature demonstrating its potential harmful effects on different taxa. Reviews can be found summarizing state-of-the-art research for marine mammals (e.g., Nowacek et al., 2015, 2007; Southall et al., 2007; Weilgart, 2007), sea turtles (Nelms et al., 2016), fishes (Popper and Hastings, 2009; Slabbekoorn et al., 2010), invertebrates (Moriyasu et al., 2004), and cephalopods (André et al., 2011). Several research papers also describe important experimental results for understanding either physical damage or behavioral effects in cetaceans (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2015; Castellote et al., 2012; Cerchio et al., 2014; Dunlop et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2009; Nieukirk et al., 2012), plankton (e.g., McCauley et al., 2017), sea turtles (e.g., DeRuiter and Larbi Doukara, 2012), fish – auditory damage (McCauley et al., 2003), fish – behavior (e.g., Hassel et al., 2004; Paxton et al., 2017; Slotte et al., 2004; Wardle et al., 2001), and fish – behavior and catch rates (Engås and Løkkeborg, 1996; Lokkeborg et al., 2012; Streever et al., 2016).

MSS environmental licensing and biodiversity in BrazilBrazil's first 2D Marine Seismic Survey was conducted in 1957, in Alagoas State continental shelf, whereas the pioneer 3D survey (denser, contiguous lines of survey) took place in 1978, in Cherne Field in Campos Basin (de Mendonça et al., 2004). However, the intensification of Brazilian coast exploration dates back to the opening of the market to foreign companies in 1997, through Federal Law 9.478/97. As a consequence of that opening, the regulatory institutional framework evolved accordingly with the creation of the National Petroleum Agency (ANP) and the environmental licensing office in the Federal Environmental Agency (IBAMA). In Brazil, the environmental licensing is an administrative procedure based upon the environmental impact assessment (EIA) process and applied to potentially harmful activities. The first Marine Seismic Survey licensing application IBAMA reviewed was in early 1999 – probably the first time a MSS went through any environmental oversight in Brazil – a process that is now entering its age of majority at 18 years.

In this period, IBAMA had to develop the expertise to understand and deal with the environmental consequences of Marine Seismic Surveys, as well as the social conflicts eventually associated with the activities. Initially running with the aid of consultants, it was not until 2002 that the first public officers were hired to IBAMA's Oil and Gas Licensing Office (Vilardo, 2007), enabling actual institutional learning and advancement of procedures. Those early days of environmental licensing practice of MSS in Brazil were characterized by a high degree of uncertainty and a very controversial debate between industry and regulators over its potential effects.

IBAMA's strategy to deal with this scenario was two-fold. The first path was to take advantage of the globalized nature of the seismic industry and develop national mitigation guidelines based on international best practices. Those guidelines were first issued in 2005 (IBAMA, 2005) and have been evolving since then using feedback from the field practice. Besides establishing mitigation measures for protection of marine mammals and sea turtles, the guidelines also provided a standardized reporting framework for the monitoring records. This means that data on the occurrence and distribution of marine mammals in Brazilian waters are being recorded in a standardized way since 2005, using trained professionals with a marine biology, oceanography or similar degree. This collection has more than 8000 individual sightings so far, producing information of great value to conservation that would never be available otherwise. Taking into account the potential data quality issues attached to such datasets (observer mistakes, for example), the recorded observations may enable scientific analysis in a variety of ways: as single observations (e.g., Fernandes et al., 2007), using a MSS as sampling unit (e.g., Gurjão et al., 2004) or even a more longitudinal assessment, like Stone and Tasker (2006) did with data from 201 surveys in the United Kingdom.

A great step toward using this register for decision-making and conservation planning was the migration of the IBAMA database to SIMMAM (Univali, 2017), an online opensource platform that integrates sightings and strandings data from the institutions that are part of the Brazilian Aquatic Mammals Stranding Network – REMAB (Barreto et al., 2012) and from academic research groups. The platform is free, and while individual researchers are allowed to establish secrecy of the marine mammals data they input in SIMMAM, all MSS-related data is considered public information and can be accessed by anyone.

Another highlight of the Brazilian MSS mitigation regulation is the existence of seasonal restriction areas for the protection of sensitive behaviors of marine mammals and sea turtles. In a context of growing concern among the marine conservation community, IBAMA pioneered this kind of approach since 2003, when a Humpback whales’ (Megaptera novaeangliae) breeding ground was defined as out of reach for seismic surveys from July to November. After this first experience, other restricted areas and periods were developed for protection of Southern Right whales (Eubalaena australis), Franciscana dolphins (Pontoporia blainvillei), Manatee (Trichechus manatus), and sea turtles (main nesting areas of the five species that occur in Brazil). After several years of practical implementation, those closed areas for MSS were finally absorbed into formal regulation in 2011 (IBAMA/ICMBio, 2011a,b). To date, Brazilian guidelines appear to remain one of the few in the world to establish such closed areas – certainly the only in Latin America (Reyes Reyes et al., 2016) – despite the ample recognition of the effectiveness of such measures. Those closed seasons and the mitigation/monitoring guidelines have put Brazil in a highlighted position among international practice (see, for instance, Compton et al., 2008; GHFS, 2015; Reyes Reyes et al., 2016; Weir and Dolman, 2007).

The second path IBAMA trailed to deal with the uncertainties of Marine Seismic Surveys impacts was to foster a national contribution for the international effort aimed to address the existing knowledge gaps. Once the EIA process for offshore activities was usually based on secondary data (due to budgetary and time restrictions), IBAMA's approach involved the commissioning of research initiatives as conditions for the licenses granted. The scope of the research to be commissioned depended on the characteristics of the project being assessed and the area in which it would be developed.

While some of the research initiatives commissioned to date were single undertakings, destined to address a specific question involving seismic surveys impacts on biodiversity, others became regular monitoring programs for areas of higher environmental sensitivity, like the beaches monitoring projects, for example.

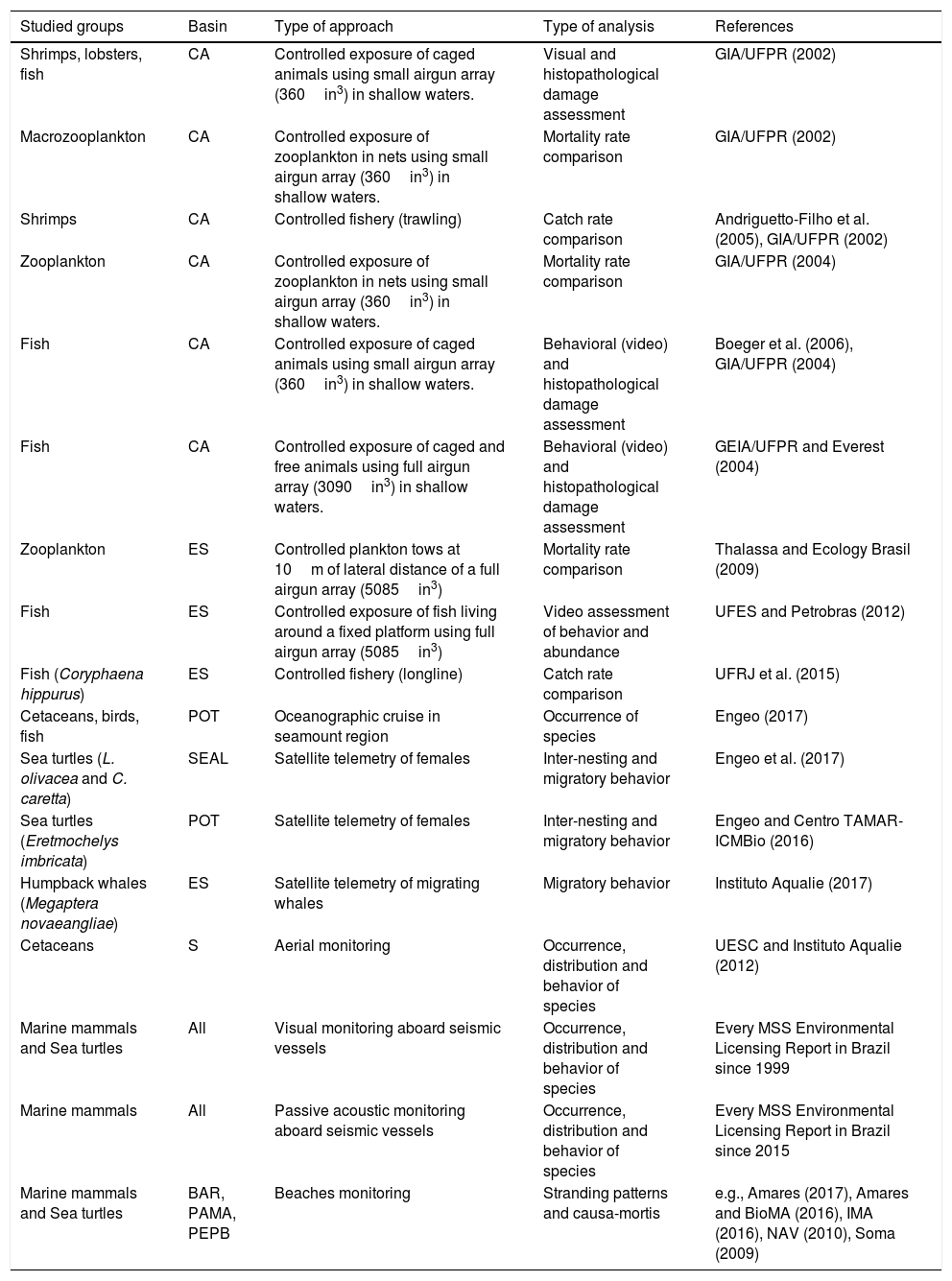

Table 1 summarizes the main research initiatives commissioned by IBAMA's request in Marine Seismic Surveys EIA processes to date. One important shortcoming to be highlighted is the low amount of peer-reviewed publications derived from those initiatives. This means that most of the knowledge generated in this process is trapped inside Technical Reports submitted to IBAMA to fulfill administrative obligations – despite the fact that there are several results of potential international relevance. One desired outcome of this short paper is exactly to foster academic interest by providing a useful index of those initiatives. All the information within such reports are considered of public domain and, therefore, can be accessed in IBAMA's EIA documentation center. Unfortunately, some of the older data will not be available in digital formats, but nevertheless it could be retrieved from the printed reports with some effort.

Summary of the main research initiatives commissioned through IBAMA's environmental licensing requirements. All the Environmental Licensing Reports cited are available in the Documentation Center of the IBAMA Oil and Gas Office, located in Rio de Janeiro. Basins: BAR-Barreirinhas, CA-Camamu/Almada, ES-Espírito Santo, PAMA-Pará/Maranhão, PEPB-Pernambuco/Paraíba, POT-Potiguar, S-Santos, and SEAL-Sergipe/Alagoas.

| Studied groups | Basin | Type of approach | Type of analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrimps, lobsters, fish | CA | Controlled exposure of caged animals using small airgun array (360in3) in shallow waters. | Visual and histopathological damage assessment | GIA/UFPR (2002) |

| Macrozooplankton | CA | Controlled exposure of zooplankton in nets using small airgun array (360in3) in shallow waters. | Mortality rate comparison | GIA/UFPR (2002) |

| Shrimps | CA | Controlled fishery (trawling) | Catch rate comparison | Andriguetto-Filho et al. (2005), GIA/UFPR (2002) |

| Zooplankton | CA | Controlled exposure of zooplankton in nets using small airgun array (360in3) in shallow waters. | Mortality rate comparison | GIA/UFPR (2004) |

| Fish | CA | Controlled exposure of caged animals using small airgun array (360in3) in shallow waters. | Behavioral (video) and histopathological damage assessment | Boeger et al. (2006), GIA/UFPR (2004) |

| Fish | CA | Controlled exposure of caged and free animals using full airgun array (3090in3) in shallow waters. | Behavioral (video) and histopathological damage assessment | GEIA/UFPR and Everest (2004) |

| Zooplankton | ES | Controlled plankton tows at 10m of lateral distance of a full airgun array (5085in3) | Mortality rate comparison | Thalassa and Ecology Brasil (2009) |

| Fish | ES | Controlled exposure of fish living around a fixed platform using full airgun array (5085in3) | Video assessment of behavior and abundance | UFES and Petrobras (2012) |

| Fish (Coryphaena hippurus) | ES | Controlled fishery (longline) | Catch rate comparison | UFRJ et al. (2015) |

| Cetaceans, birds, fish | POT | Oceanographic cruise in seamount region | Occurrence of species | Engeo (2017) |

| Sea turtles (L. olivacea and C. caretta) | SEAL | Satellite telemetry of females | Inter-nesting and migratory behavior | Engeo et al. (2017) |

| Sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) | POT | Satellite telemetry of females | Inter-nesting and migratory behavior | Engeo and Centro TAMAR-ICMBio (2016) |

| Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) | ES | Satellite telemetry of migrating whales | Migratory behavior | Instituto Aqualie (2017) |

| Cetaceans | S | Aerial monitoring | Occurrence, distribution and behavior of species | UESC and Instituto Aqualie (2012) |

| Marine mammals and Sea turtles | All | Visual monitoring aboard seismic vessels | Occurrence, distribution and behavior of species | Every MSS Environmental Licensing Report in Brazil since 1999 |

| Marine mammals | All | Passive acoustic monitoring aboard seismic vessels | Occurrence, distribution and behavior of species | Every MSS Environmental Licensing Report in Brazil since 2015 |

| Marine mammals and Sea turtles | BAR, PAMA, PEPB | Beaches monitoring | Stranding patterns and causa-mortis | e.g., Amares (2017), Amares and BioMA (2016), IMA (2016), NAV (2010), Soma (2009) |

There are, of course, risks and limitations of the knowledge generation embedded in environmental impact assessment processes. Obtaining scientific valid data from monitoring programs depends on several variables, like proper sampling design, adequate survey effort and methodological consistency, as recently argued by Dias et al. (2017). Nevertheless, we believe that the vast majority of the results generated through MSS EIA-related projects can be considered good science and would constitute publishable material if given proper academic treatment.

Other important topic of concern that is worth mentioning is the potential bias that industry funding can impose over such studies, however closely overseen they might be by governmental institutions like IBAMA. Wade et al. (2010) found evidence of bias in papers assessing anthropogenic noise effects in marine mammals, depending on which institution funded the research. One tentative way to minimize this kind of problem would be to prioritize public universities and research centers as implementing institutions, aiming at their independence and public commitment. But unfortunately, practice has shown that this does not completely solve the bias issue – as there are several ways in which the sponsor can influence the outcomes of the research. It can range from direct pressure or even censorship to more subtle means, as the potential for future contracts with the same contractor. Adding to the complexity, university-led projects in Brazil are said to be harder to manage (due to cumbersome administrative bureaucracy) and not always yield the follow-up peer-reviewed publications as expected, due to competing priorities in the Academy (like the need to secure the next grant or contract in a chronically underfunded research environment).

A different approach to minimize possible bias and to avoid environmental licensing constraints of time and scope would be to establish research funds managed by an independent body. This financial mechanism should have a governance design to ensure fair selection of implementation partners and project accountability. There are several examples of such arrangements in Brazil and elsewhere, with specific purposes and formats, and the designing of a tailor-made mechanism to fund MSS-related research should learn from those experiences.

Concluding remarks and reforming risksMarine Seismic Surveys have been a major source of concern for marine biodiversity conservationists in the past decades. It is critical that the knowledge over its effects on marine life continue to improve – and Brazil's 18-year regulatory experience and well acknowledged mitigation requirements puts the country in a privileged position to contribute to that objective. There have been many relevant research initiatives commissioned through the environmental licensing process so far – but a better communication of the results is still a challenge to be addressed.

Despite all the evolution summarized in this paper, environmental control of Marine Seismic Surveys in Brazil seems endangered from both external (legal) and internal (institutional) menaces. One important external source of risk is the systemic reforming proposals that are currently being discussed in the National Congress, which can severally undermine effectiveness of Brazilian licensing system (see discussion in Bragagnolo et al., 2017; Fonseca et al., 2017), threatening the environmental oversight of activities like MSS. We fear that a new regulation would impose an over-streamlined process, as seen recently in some Brazilian states (Fonseca and Rodrigues, 2017) and in other countries (Bond et al., 2014), reducing IBAMA's ability to promote effective mitigation and adequate public participation in the environmental licensing decision-making.

The other menace is internal and maybe harder to understand and identify its origin. An institutional reform in IBAMA's Environmental Licensing Directorate (DILIC) has just dismembered the Oil and Gas Office (CGPEG) in Rio de Janeiro, removing the MSS licensing responsibility to the central DILIC office in Brasília, without any reasonable justification. The newly published internal regiment places seismic surveys activities along with ports, marine minerals mining and other marine infrastructure in a Coordination in DILIC's central office in Brasília, while keeping the other activities of the oil and gas chain (drilling and production) in Rio de Janeiro, where the Oil and Gas Office is located since 1998. The experienced staff of the Seismic Surveys team are to be redistributed to other activities in Rio de Janeiro, while IBAMA creates from zero a new team in Brasília office. This obscure management option seems even more unusual in a time of severe budget constraints, when there are no funds available for capacity building and new public tenders for staff increasing are practically out of the question.

This hard-to-explain change has puzzled most of the actors involved in MSS environmental licensing process, gathering important support from outside IBAMA, as shows an open letter signed by 24 researchers and institutions involved in marine biodiversity conservation in Brazil (Magalhães et al., 2017). Despite being already formalized in IBAMA's new internal regiment, the described changes were still not effective at the time of writing (August 2017), but it would certainly be a huge loss to see this 18-year old legacy becoming history for some idiosyncratic reforming. In difficult times such as the present, it is of paramount importance that we preserve the positive experiences and halt the throwbacks in the conservation agenda.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone.

The authors would like to express gratitude and acknowledge the great contribution of several Environmental Analysts that have worked in IBAMA's Oil and Gas Office in these 18 years and showed that, despite all the challenges and constraints, it is possible to achieve excellence in the public service in Brazil. We also thank the numerous researchers, analysts and marine mammal observers (MMO) that have contributed to generate science from the environmental licensing process.