Introduction of species beyond their natural geographic distribution is a major concern for both human well-being and health ecosystems. One of those species is the wild boar Sus scrofa and its feral varieties. Feral forms of S. scrofa figure amongst the harmful alien invasive species (Lowe et al., 2000), because of its impacts on natural and agricultural ecosystems. It has the wider distribution among all terrestrial mammals in the world, and its effects on ecosystem functioning have been broadly recognized (Barrios-García and Ballari, 2012). A set of traits such as plasticity in feeding behavior (Ballari and Barrios-García, 2014) and high reproductive rates (Dzieciołowski et al., 1992), are associated to the ability of feral pigs to thrive wherever they are introduced.

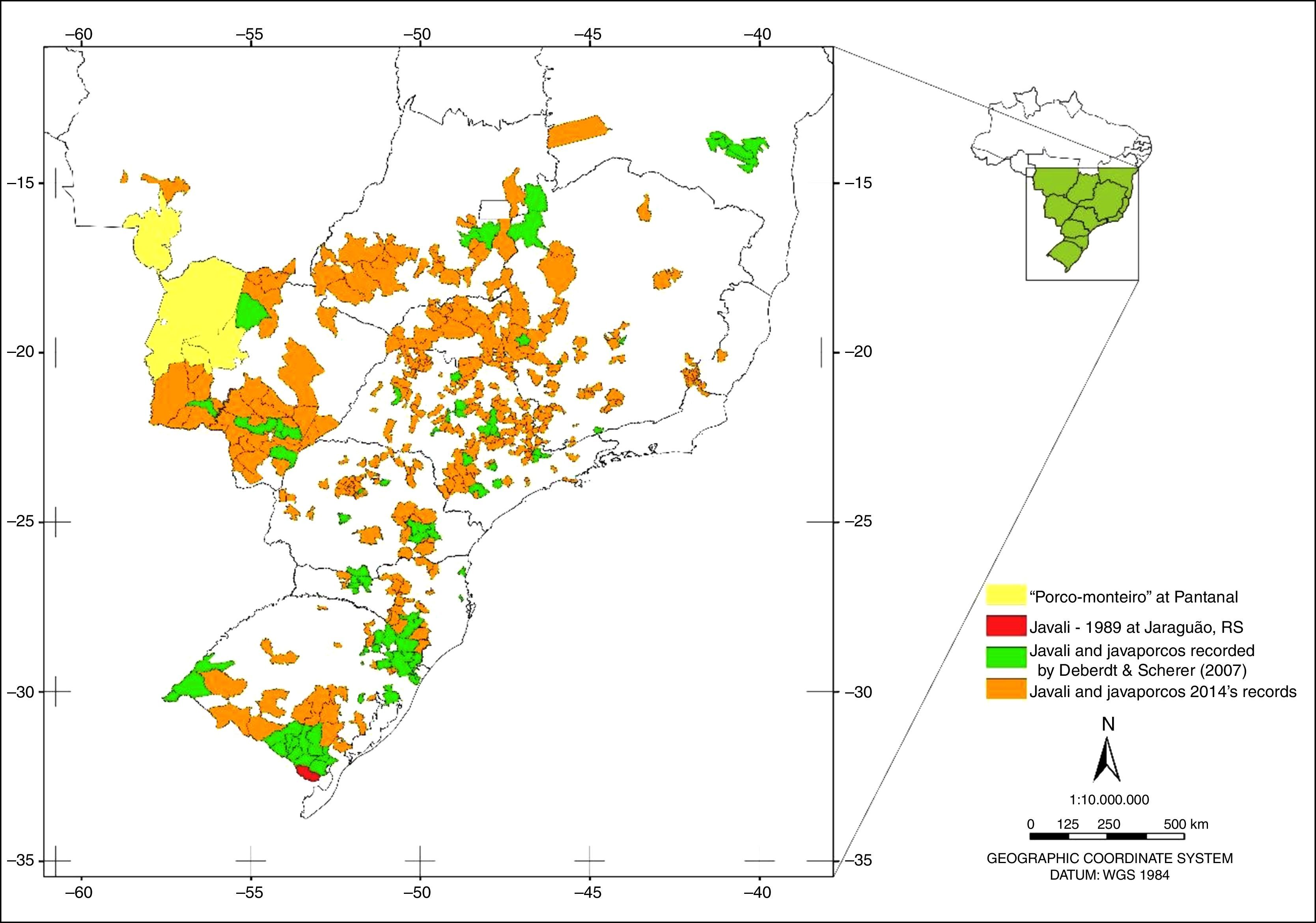

In Brazil, feral pigs first invaded Pantanal ecosystems. They are locally known as “porco-monteiro”, a breed of domestic pig that escaped into the wild more than 200 years ago (Desbiez et al., 2011). The second wave of invasion of feral pigs in Brazil took place in 1989, coming from Uruguay, when wild boars invaded the south part of Rio Grande do Sul, south of Brazil (Deberdt and Scherer, 2007). The third wave differs from the two others by context and magnitude. Wild boars were imported in the 1990s from Europe and Canada by swine farmers which trusted in a new commercial appeal, sold to them as “the blue blood in the pigpen”, referring to the suppose royalty origin of the species as being a meat of a higher quality (GloboRural, 1996). The commercial promises proved unprofitable. Trying to save the business, many farmers bred wild boars with domestic pigs, intending a fattest pig. In fact, the breed resulted a half-bred S. scrofa, bigger than and skittish as pure wild boars, known as “javaporco”. By the end of the same decade, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) suspended the importation and stopped to concede operating permits to established “exotic” swine farmers (IBAMA, 1998a,b). What followed was a widespread intentional (in some cases unintentional) release of half-bred feral pigs (and pure wild boars), in discontinued locations, inaugurating a continental scale invasion (Fig. 1).

Distribution of feral pig populations and its varieties in Brazil. It first invaded Pantanal ecosystem, where they are locally known as “porco-monteiro” (yellow). Wild boars appeared in Jaguarão-RS in 1989 (red), coming from Uruguay. The records from 2007 (green) are from Deberdt and Scherer (2007), and indicate all feral swine forms. The present work gathered records in the year of 2014 (orange). For complete list of the municipalities, see supplementary material.

We encouraged a broad network of people attentive to the issue of feral pigs in Brazil to participate in the effort to gather information on the location of incidence of these animals (http://aquitemjavali.blogspot.com.br). This effort took place from May to December 2014. Legalized feral pig hunters accounted for the majority of the gathered records. They felt comfortable in sharing information, because since 2013 a new rule from IBAMA (IN 03/2013) allow for the persecution and slaughter of feral pigs aiming at controlling their population size. It was surprising to note that there are many feral pig hunters in activity and aware that the impacts caused by these animals may get out of control. To avoid misleading information from the collaborative network, the only valid information considered was from reports accompanied by pictures from slaughtered or sighted animals.

Along with that, we collected data together with São Paulo State Environment Secretariat (SMA). The SMA of São Paulo implemented the Work Group in Exotic Species, which efforts resulted in an up to date publication about alien species invasion in the state (SMA, 2013). We also checked processes from IBAMA sent to SMA in the year of 2014, from citizens of São Paulo requesting authorization to control feral pig in third land, and these processes provided new records to us. The media also contributed, since the news about crop damage and other troubles associated to feral pig activity became recurrent, thereby we also accounted the publicized places.

We found that feral pigs are present in 472 Brazilian municipalities, in four of the five political regions of the country, presenting a pattern of regionally isolated populations (Figs. 1 and Table S1). The most affected region is the southeast (253 municipalities), followed by south (133), midwest (75) and northeast region (9). São Paulo is the most affected state (156 municipalities) followed by Minas Gerais (91) and Rio Grande do Sul (55) (see supplementary material). Our records represent an increase of five times on the number of locations invaded since Derbedt and Scherer (2007; 91 municipalities). We are watching an unforeseen invasion (Kaizer et al., 2014; Trovati and Munerato, 2013).

It is well recognized that feral pigs might cause several economic injuries, whether damaging crop fields and attacking livestock or causing indirect losses associated to the budget involved in control programs (Deberdt and Scherer, 2007; Pimentel et al., 2005). An important agro industry from São Paulo reported us its losses: 340ha of maize crop in a year, equivalent to 2.84 thousand tons of grains or around R$1.25 million ($430.000 dollars). It is also reported in the literature that the ecological impacts of feral pigs are related with its rooting and wallow behavior, which may reduce the cover and diversity of plant species (Hone, 2002), affect soil properties (Barrios-García et al., 2014) and also assist the spread of diseases to wild life (Pejchar and Mooney, 2009). Feral pigs also contribute to the spread of invasive plants (Dovrat et al., 2012).

The current federal plan to control feral pig populations, the IN 03/2013, was edited primarily to protect macro-economic interests. The Brazilian swine business earns 1.5 billion dollars annually from international markets (ABPA, 2014), and the invasion of feral pigs might put that market at risk. The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) modified the rules and procedures to certify the country members as classical swine fever (CSF) free zones (OIE, 2013). Before 2015, CSF was an auto declared disease and the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture (MAPA) recognized most of the country as CSF free zone (MAPA IN 52/2013), but now it needs an official recognition from OIE, otherwise Brazilian swine products cannot be exported. The national recognition of CSF free zones emerged from MAPA through the Swine Health National Program (MAPA, 2012), and since 2012 the Brazilian Corporation for Agricultural Research (EMBRPA) implemented the epidemiological surveillance in feral swine (EMBRAPA, 2012), attending to an official request from MAPA. Including EMBRAPA expertise in the PSC question is strategic to assure international recognition and keep the market. Therefore, the main motivation to promote and authorize control of feral pigs in Brazil is to prevent a rupture in both ongoing and future commercial relations with international markets.

There is a perception that the harmful effects of feral pigs are associated to high densities in both native and introduced ranges (Hone, 2002; Ickes, 2001), suggesting a threshold of pig densities above which they become noxious. Does this threshold really exist? If so, how to measure it? Below which threshold will feral pigs become harmless to economic interests and to biodiversity and ecosystem services? Is the economic and ecological threshold similar? Given the speed of invasion throughout new ranges presented in this work, we believe that control programs are necessary, despite being difficult to implement. Most of the successful experiences come from islands (in which eradication was achieved, see Cruz et al., 2005; Parkes et al., 2010 and references therein). Continental programs fail to eradicate due to the high capacity that feral pigs have to recover and learn to avoid persecution (Morrison et al., 2007), suggesting we should assume the control perspective to deal with that matter.

Finally, the IN 03/2013 relies on the action of hunters to stop the advance of feral pigs in Brazil. This leads to an awkward situation: on the one hand feral pigs may be acting as a shield to other mammals, since they are favorite species of locals for food ingestion (Desbiez et al., 2011), but there is also an evident concern about the increase in wildlife persecution, because most Brazilian ecosystems are highly defaunated due to uncontrolled hunting (Galetti et al., 2009; Peres and Palacios, 2007). Even if in near future a new rule determines the prohibition of feral pig control, they may keep doing it, as they have being doing before the legalization. What becomes evident is the need for a regulation on this hunting activity, as it will be a critical part in management of feral pig and other invasive species in near future. For instance, the hare Lepus europaeus, another invasive species (Auricchio and Olmos, 1999) are affecting the economy of small vegetable producers and cannot be legally controlled. The Brazilian Law 5197/1967, historically assumed by the epithet “Fauna Protection Law”, in fact does not prohibit hunting activity. This law also known as “Hunting Code”, is a bottleneck in wildlife management, by neglecting to understand technically and scientifically the ecological and economic aspects of invasive species in Brazil.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank to FAPESP (Biota 2014/50434-0), SISBIO (no. 46150), IDEAWILD, SMA-SP, C. C. de Oliveira and to all collaborators who send information to http://aquitemjavali.blogspot.com.br. FP receives a fellowship from CAPES and MG receives a fellowship from CNPq.