Botanical gardens hold a large potential for biodiversity conservation (Ashton, 1988), a topic which has been on international agendas (Maunder, 1994; Wyse Jackson and Sutherland, 2000) for decades. Tropical botanical gardens (TBGs) in particular hold unutilized conservation potential, as they are usually located in hotspots of biodiversity that undergo rapid degradation (Chen et al., 2009). However, by nature, the emphasis of botanical gardens—and researchers who use botanical gardens as their study sites—lies on ex situ and in situ conservation of plants (Hurka, 1994; Chen et al., 2009; Donaldson, 2009; Cibrian-Jaramillo et al., 2013). In addition, the role of botanical gardens in environmental education and raising conservation awareness has received substantial interest (e.g., Suh and Samways, 2001; He and Chen, 2012). Yet, despite the notion that botanical gardens play a role in the conservation of habitat remnants (Pinheiro et al., 2006), the role of botanical gardens for conservation of fauna goes largely unaddressed. Here, I highlight the potential that TBGs hold for animal conservation by providing a case study and pointing out questions we might address on this topic. Ideally, this will invite discussion on the direct role botanical gardens could play in animal conservation, and perhaps even stimulate explicit inclusion of this topic on international agendas. As such, this paper adds one particular point—the role for animal conservation—to a previous assessment on the potential of TBGs for in situ and ex situ conservation of plants; taxonomic, botanical and horticultural research and activities; and public education on natural history and conservation issues (Chen et al., 2009).

Methods and resultsI searched the ISI Web of Science and Scopus for all literature (regardless of publication date) that addresses ‘a link’—however broad or indistinct this link may be—between animal richness, diversity or conservation and botanical gardens, using a combination of the terms botanic(al) garden and either fauna or animal. In order to increase the number of results, I also searched with botanic(al) garden and one of the taxonomic groups reptiles, birds, or insects as search terms.

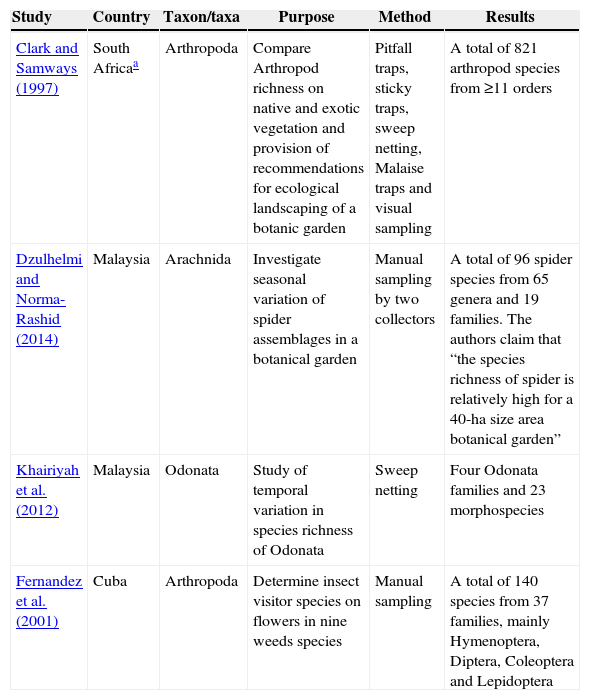

Relevant results were sparse. Many of the search results related to topics irrelevant to this review (e.g., parasite infection risk of domestic dogs as a result of botanical garden visits). Thus, I manually filtered the search results for relevance and found not one systematic study on the topic of faunal diversity, richness or conservation in botanical gardens (ergo, not one on ‘tropical’ botanical gardens either). Some more rudimentary (or taxon limited) aspects of animal richness or diversity in TBGs can be inferred from at least four peer-reviewed publications (Table 1).

Examples of studies on some aspect of animal diversity or richness in tropical botanical gardens (TBGs). None of these studies includes a systematic assessment of animal richness or diversity in the entire TBG that served as study site, but rudimentary numbers illustrate the potentially high levels of biodiversity that may be supported by TBGs.

| Study | Country | Taxon/taxa | Purpose | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark and Samways (1997) | South Africaa | Arthropoda | Compare Arthropod richness on native and exotic vegetation and provision of recommendations for ecological landscaping of a botanic garden | Pitfall traps, sticky traps, sweep netting, Malaise traps and visual sampling | A total of 821 arthropod species from ≥11 orders |

| Dzulhelmi and Norma-Rashid (2014) | Malaysia | Arachnida | Investigate seasonal variation of spider assemblages in a botanical garden | Manual sampling by two collectors | A total of 96 spider species from 65 genera and 19 families. The authors claim that “the species richness of spider is relatively high for a 40-ha size area botanical garden” |

| Khairiyah et al. (2012) | Malaysia | Odonata | Study of temporal variation in species richness of Odonata | Sweep netting | Four Odonata families and 23 morphospecies |

| Fernandez et al. (2001) | Cuba | Arthropoda | Determine insect visitor species on flowers in nine weeds species | Manual sampling | A total of 140 species from 37 families, mainly Hymenoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera and Lepidoptera |

I acknowledge that some relevant articles might have gone unnoticed due to the fact that a lot of research in tropical countries is published in local journals that are not indexed in Scopus or Web of Science, or because they are written in other languages. It is, however, obvious that there are very few studies published on the matter. This is surprising because many of us are intuitively aware of the wealth of biodiversity often found in botanical gardens. In fact, we regularly choose these places as our study sites for research on animals (but not necessarily on richness, diversity or conservation topics; e.g., Shang-Yao et al. (2010) on bird breeding biology). Moreover, we are aware that botanical gardens can be of importance in maintaining ecological processes and preserving habitat (Pinheiro et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2009) and that that urban areas are not wildlife wastelands. Rather, with the right focus (e.g., in landscape design), gardens and green spaces in urban areas can serve as habitat for many animal species (Koh and Sodhi, 2004; Goddard et al., 2010).

Green spaces in cities can serve as de facto sanctuaries for certain animal species (Hunter and Hunter, 2008), and these areas play an increasingly imperative role in the maintenance of global biodiversity considering current exurban growth. Compared to other urban green spaces, botanical gardens in general are usually high in plant species richness, and animal species richness—which often correlates with plant richness—is also therefore expected to be high (Fernandez et al., 2001). If we then consider that native plant species richness is highest in tropical regions, and that TBGs have the potential to conserve many native plant species within their native climate and range (Chen et al., 2009), we could conclude that these TBGs hold vast potential to accomplish something that is often considered secondary to their mission in plant conservation: conservation of large numbers of native animal species.

One illustrative example of a TBG, the Dr. Rafael Ma. Moscoso National Botanical Garden (JBSD) in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, seems to provide habitat for a large number of species (Box 1). Moreover, many species found here are actually endemics (e.g., twenty observed bird species are endemic to the island of Hispaniola). This may not seem surprising, as this TBG includes a fairly large (∼0.8km2) remnant of natural vegetation (the importance of such an area in TBGs is discussed in Pinheiro et al. (2006)) and levels of endemism of small-sized taxa are relatively high on tropical islands (Ricklefs and Bermingham, 2008). TBGs on islands (like the JBSD) may thus be in a particularly unique position to form sanctuaries for endemics, especially when located in a biodiversity hotspot like the Caribbean (Myers et al., 2000). Unfortunately, such hypotheses largely go untested due to the lack of studies on the topic.

Example: Dr. Rafael Ma. Moscoso National Botanical Garden (JBSD)

The JBSD in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, is a ∼2km2 garden fully enclosed by urban development. The JBSD ranks relatively low in plant species richness (∼300 species, unpublished data) and age (founded in 1976), when compared to the median plant richness of 2500 species and median founding date of 1952 of 242 botanical gardens across the world (Pautasso and Parmentier, 2007). However, it is nearly 20 times the median size of 12ha, and contains a large stretch (∼40% of the garden) that is designated as ‘natural reserve’, an area dominated by native flora. Likely due to this abundance in native flora, fauna is ubiquitous throughout the garden.

Certain fauna are so pervasive that they are obvious to scientists and regular visitors alike. For example, 109 bird species have been documented in the garden on the citizen science platform eBird (http://ebird.org/;Sullivan et al., 2009). I will not focus on accuracy and detection bias issues involved with these data—e.g., the large number of visitors to this garden would skew any comparisons with other parts of the country—but it is illustrative that 109 species constitute more than one-third of all 259 species listed for the entire Dominican Republic on eBird (and nearly a third of the 306 species recorded in the Dominican Republic in general (Perdomo and Arias, 2009)).

There are only three places in the country with higher numbers of species recorded on eBird. The highest number is recorded in Rabo de Gato, a known birding locality at the fringes of the Important Bird Area (IBA) Sierra de Bahoruco (133 species). Strikingly, numbers of species recorded in some IBAs and protected areas, like P.N. los Haitises (95 species) and Reserva Científica Ebano Verde (82), are lower than those recorded in the JBSD. I do not argue that the JBSD is more important than these areas, as these protected areas might have considerably higher conservation value with regards to factors such as sustenance of large populations, rare species, and threatened species (Perdomo and Arias, 2009). Yet, this ∼2km2 garden clearly plays a role in the provision of potential habitat for bird (and likely other) species, a factor worthy of further investigation (Table 1).

Unfortunately, few systematic surveys of richness of any taxa have been conducted in the JBSD, or in the Dominican Republic in general. The collection of the National Natural History Museum in Santo Domingo is illustrative in that sense. For example, it contains Lepidoptera specimens collected from all over the country (∼160 species) and the metropolitan area of Santo Domingo (∼61 species). Yet, only few specimens (∼16 species) were collected in the Botanical Garden. This is interesting because many of the collected specimens in Santo Domingo come from urban parks that are both smaller and less diverse in flora than the JBSD. Research on animal taxa in the JBSD seems thus underutilized, and it might be worthwhile to enhance research collaborations and increase sampling in the JBSD.

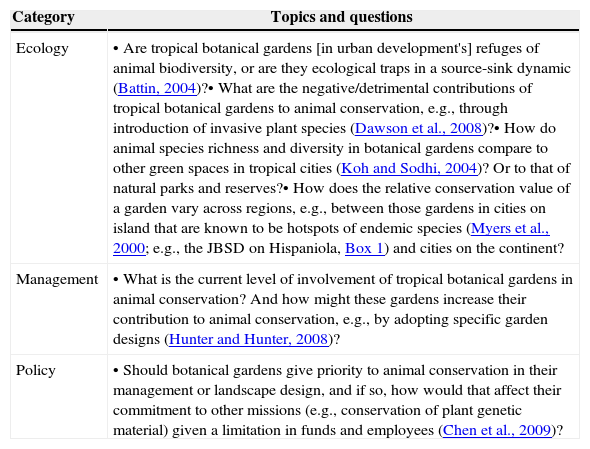

The lack of published peer-reviewed articles with a focus on animals in TBGs indicates a missed opportunity. We should expand on our ‘intuitive feeling’ that TBGs are hosts to high animal diversity, and explore the role these green spaces have for conservation now or, potentially, in the future. Such a research effort would be parallel to earlier analyses on the link between conservation of floral diversity and TBGs (e.g., Pinheiro et al. (2006)). I propose an expansion of research on the value of TBGs for animal conservation (Table 2). For example, reflecting on the particularities of the aforementioned garden, the JBSD (Box 1), the questions arise easily and multifold: (1) Do all these species actually reproduce in the garden, or is the garden an ecological trap?; (2) Is the role of this garden relatively large given its location on an island in a hotspot of endemism, as compared to other TBGs on the mainland?; and, 3) Do current garden management policies address animal conservation or should this point receive enhanced attention?

Potential research topics regarding the role of tropical botanical gardens in animal conservation.

| Category | Topics and questions |

|---|---|

| Ecology | • Are tropical botanical gardens [in urban development's] refuges of animal biodiversity, or are they ecological traps in a source-sink dynamic (Battin, 2004)?• What are the negative/detrimental contributions of tropical botanical gardens to animal conservation, e.g., through introduction of invasive plant species (Dawson et al., 2008)?• How do animal species richness and diversity in botanical gardens compare to other green spaces in tropical cities (Koh and Sodhi, 2004)? Or to that of natural parks and reserves?• How does the relative conservation value of a garden vary across regions, e.g., between those gardens in cities on island that are known to be hotspots of endemic species (Myers et al., 2000; e.g., the JBSD on Hispaniola, Box 1) and cities on the continent? |

| Management | • What is the current level of involvement of tropical botanical gardens in animal conservation? And how might these gardens increase their contribution to animal conservation, e.g., by adopting specific garden designs (Hunter and Hunter, 2008)? |

| Policy | • Should botanical gardens give priority to animal conservation in their management or landscape design, and if so, how would that affect their commitment to other missions (e.g., conservation of plant genetic material) given a limitation in funds and employees (Chen et al., 2009)? |

TBGs can enhance their role in animal conservation, for example through landscape design that increases animal species richness. This might be realizable without limiting the other goals of TBGs, such as visitor education, visitor enjoyment, and plant conservation (e.g., in lines with Suh and Samways (2001)). For example, a current development in the JBSD is to implement a butterfly garden, mainly as a visitor attraction. Such a development could serve a great double-function for animal conservation as it could provide habitat for numerous species if there is a certain diversity of host plants (Koh and Sodhi, 2004). To achieve this however, would require a minimal understanding of butterfly (and perhaps hummingbird, bee, etc.) ecology plus the consideration of ‘animal conservation’ as a factor in this botanical garden's landscaping policies. In other words, management recommendations such as “patches of different ecotypes should not be separated by more than a few meters by expanses of mown lawn to ensure high arthropod diversity” (Clark and Samways, 1997), might greatly enhance the potential of TBGs for animal conservation if they would be adopted by TBG management.

TBGs are in a unique position to facilitate biodiversity conservation if they engage in in situ ecosystem management. However, TBGs also face many challenges (for a summary, see Chen et al. (2009)), especially a lack of funding. TBGs might benefit from increased recognition of their full or potential conservation value, e.g., in their struggle to receive funds. Similarly, global animal conservation efforts might receive a boost if ‘protecting animal diversity’ became a part of a ‘holistic approach’ to botanic garden management (as briefly proposed, but not expanded on, in the International Agenda for Botanic Gardens in Conservation (Wyse Jackson and Sutherland, 2000)). The importance of TBGs for animal conservation should be recognized as more than a ‘side effect’ of habitat protection or plant diversity conservation, and made explicit part of the conversation on the current and future roles of botanical gardens (TBGs in particular) for conservation (Maunder, 1994; Wyse Jackson and Sutherland, 2000; Chen et al., 2009; Donaldson, 2009; Faggi et al., 2012).

It is unlikely that urban expansion will slow down any time soon, and thus we face the task of conserving species in increasingly human-dominated environments (Koh and Sodhi, 2004). TBGs, with proper strategies and more background research, could be essential to this cause.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

I would like to thank the people at the National Botanical Garden and Natural History Museum of Santo Domingo for their insights and collaboration, especially Gabriel de los Santos and Francisco Paz, the birders that submitted their observations to eBird for their data, and M.C. Gallegos and A. Ozelski-McKelvy for recommendations and insights that improved this manuscript.