Ecologically important marine ecosystems should be identified and protected, as is the case of the poorly known SW Atlantic rhodolith beds. Understanding the main variables predicting biodiversity patterns is essential for determining priority areas for conservation. Here, we analyzed the macroinvertebrate associated with rhodoliths from euphotic and mesophotic zones from the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago investigating the drivers of diversity distribution in this habitat. Rhodoliths were sampled and vagile macroinvertebrates (>500μm) were classified and quantified. We verified that estimated density of organisms associated with rhodoliths in the euphotic zone was 17 % greater than the mesophotic zone. The communities along depth zones show dissimilarities, suggesting that both environments are ecologically distinct. Comparisons with other ecosystems revealed that rhodolith beds have similar diversity of macroinvertebrates. We also found that four of the six tested variables predicted 85 % of the variability observed in the vagile macroinvertebrate community (i.e. average diameter, depth, biomass of macroalgae and density of rhodoliths in the bed). These variables should be taken into account in future research in modeling the biodiversity associated with the rhodolith beds. This is especially relevant in the SW Atlantic where the rhodolith beds seem to harbor an associated biodiversity greater than previous works had indicated, moreover, they represent one of the main ecosystems that are often superimposed with mining activities.

The value of marine biological diversity is recognized worldwide. Ecosystems known harboring high values of diversity, however, have been quickly degraded (Halpern et al., 2008). Identify and protect marine areas that hold valuable biodiversity and provide important ecosystem services is an emerging conservation priority (Glynn, 1996; Pikitch et al., 2004; Slattery et al., 2011). Some of these areas include bottoms dominated by rhodoliths (i.e. "free-living" nodules composed of more than 50 % of encrusting coralline red algae, Corallinales, Sporolithales and Hapalidiales) (Foster et al., 2013; Richards, 2016). Besides biogeochemical changes related with rhodolith metabolism (Burdett et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2019), the structure provided by rhodoliths changes the unconsolidated and two-dimensional seabed to a tridimensional more complex bottom (Steller et al., 2003; Metri, 2006; Foster et al., 2007) increase the associated diversity in comparison with unconsolidated substrates (Steller and Foster, 1995; Steller et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2012). The ecological process in which rhodolith beds increase complexity and influence the associated diversity remains poorly understood, and is likely related to multidimensional habitat attributes such as: i) the scale, ii) the diversity of complexity-generating elements (also called heterogeneity), iii) the size of these elements, iv) their spatial arrangement, and v) the abundance of structural elements (e.g., Otero-Ferrer et al., 2019).

Abundance and diversity of macrobenthic community is influenced by habitat complexity that varies across different scales (e.g., Gratwicke and Speight, 2005; Le Hir and Hily, 2005; Gartner et al., 2013; Carvalho et al., 2017). Seagrasses, for instance, increase a large-scale complexity through its blade architecture, from small-scale discrete habitat-forming elements as seagrass holdfasts to the whole matrix constituted by meadow patches (Gartner et al., 2013). The sizes of structural elements influence the interstitial spaces among habitat units thus promote their stability and provide different conditions to the associated communities. For example, large rhodoliths where sponges can grow are stabilized and coalesced forming carbonate plates that provide sites for new structural elements such as corals (Pereira-Filho et al., 2015a).

In the scale of rhodoliths, shape, volume, amount of epiphyte algae, and trapped sediment are well known as complexity-generating elements (e.g., Steller et al., 2003; Amado-Filho et al., 2010), while the density (i.e., rhodolits.m−2) and size of rhodoliths are also important habitat attributes in driving their associated diversity (e.g., Peña and Bárbara, 2008; Bahia et al., 2010). In SW Atlantic, where rhodolith beds cover extensive areas (i.e., thousands of hundreds square kilometers), representing the highest concentration in the world (Amado-Filho et al., 2017), the effort needed to quantify the associated biodiversity has been insufficient to provide information for decision-makers to diminish habitat loss mainly caused by mining activities (e.g., Santos et al., 2016; Marques and Araújo, 2019). Thus, understanding the main patterns and processes driving the biodiversity associated with rhodolith beds is important to predict areas where higher associated biodiversity is expected. Rhodolith beds occur predominantly in mesophotic zones and have considerable CaCO3 accumulation, being areas of increasing interest for carbonates’ mining (Amado-Filho et al., 2012; Pinheiro et al., 2019). An increasing number of studies in mesophotic zones on carbonate reefs has demonstrated that mesophotic rhodolith beds may be ecologically distinct than their euphotic counterparts (Sinniger et al., 2016; Rocha et al., 2018).

Difficulties in sampling rhodolith beds from the mesophotic zone (30−150m depth) have limited the access to compare data with euphotic depths (<30m). However, new approaches involving diving techniques have made possible to collect accurate data on associated biodiversity (Amado-Filho et al., 2012; Santos et al., 2016). Here, we used such approaches to test the importance of density, volume, shape, size, trapped sediment, depth, and epiphytic algae in predicting the biodiversity of macroinvertebrates associated with rhodolith beds. In addition, we compare the macroinvertebrates associated with rhodolith beds on euphotic and mesophotic zones.

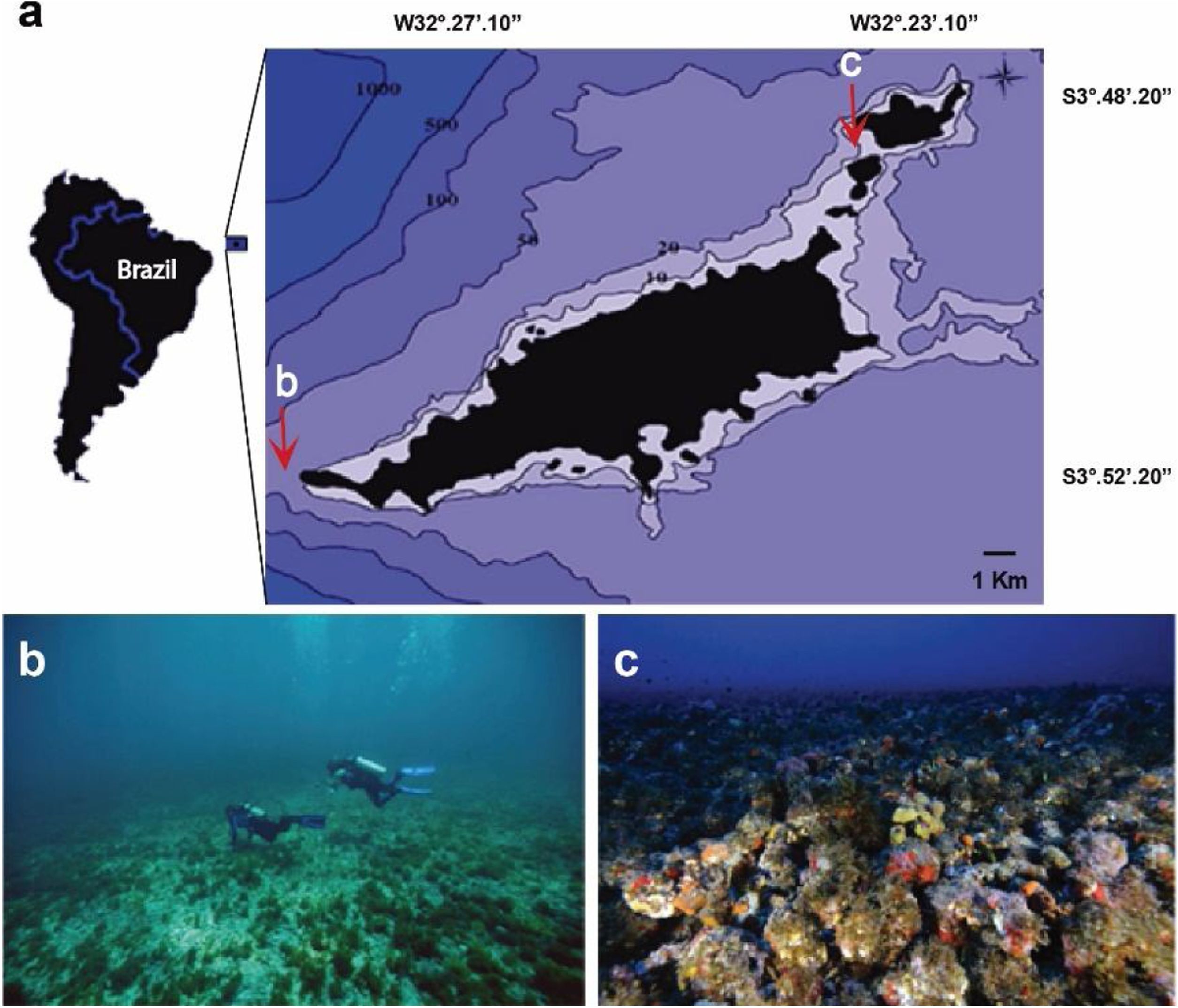

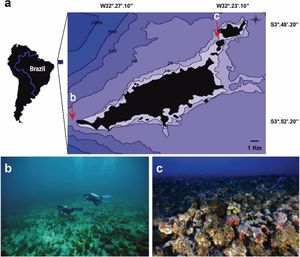

Material and methodsStudy areaThe Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (FNA) includes 21 islands located 345km from the Brazilian northeast mainland. The archipelago is under influence of the west-flowing Equatorial Current, with warm (∼26°C) and saline waters (∼36/oo). Rhodolith beds represent the main habitats of insular shelves of the archipelago from 10 to 100m depth, with soft sediments nearshore (Amado-Filho et al., 2012). Since 1988 the Archipelago is part of a National Marine Park covering an area of ∼113 km². Two sites were sampled: Ressureta and Cabeço da Sapata (Fig. 1a). Ressureta is a channel, 10−15m in depth, located between the Meio and Rata islands (3°49′00.0″S, 32°23′26.5″W). Cabeço da Sapata is a rocky outcrop that can reach up to 45m depth (3°52′40.9″S, 32°29′3.8″W). Both sites were chosen for presenting extensive rhodolith beds in the euphotic and mesophotic zones (Amado-Filho et al., 2012; Pereira-Filho et al., 2015b) (Fig. 1b and c). Rhodoliths from both depths are monospecific, and more than 60 % of them were formed by Melyvonnea erubescens (Foslie) Athanasiadis and D.L.Ballantine. However, Harveylithon rupestre (Foslie) A.Rosler, Perfectti, V.Peña and J.C.Braga, Sporolithon ptychoides Heydrich and Lithothamnion crispatum Hauck also form monospecific rhodoliths in the sampled area (Amado-Filho et al., 2012).

Data collectionThe sampling was performed in July 2012 using SCUBA in the euphotic zone (<30m depth) and mixed-gas diving techniques (TRIMIX) in the mesophotic zone (>30m depth) (dives were conducted by IPJ, GMAF, and GHPF). We sampled 20 rhodoliths from each depth site (i.e. 15m and 45m depths). After the divers have reached the site depth, rhodoliths were non-intentionally target in intervals of five diver fin kicks. Thereafter, they were individually and carefully inserted in nylons bags (500μm mesh) and fixed in 10 % formalin.

Epibionts were removed from each rhodolith using tweezers, wash bottles and brushes. The water resulting from the screening process was filtered in a 500μm mesh to avoid loss of small individuals and sediment. Vagile macrofauna was preserved in 70 % ethanol while macroalgae and sediment were stored in 4 % formalin. All specimens were separated, identified at the highest taxonomic resolution possible and quantified (number of individuals for each sampled rhodolith). Precautions were taken to prevent the overestimation of each taxonomic group. Maxillopoda, Malacostraca, Polychaeta and Sipuncula were counted only when the cephalic region was preserved. For Mollusca, we quantified only individuals who still had the soft body parts. We choose to quantify only the specimens of Ophiuroidea and Echinoidea with the central disc preserved (the list of recorded organisms and deposited collections is available in the Table S1).

After removal of epibionts, we measured the volume of the rhodoliths by liquid displacement in a becker of 500ml graduated every 10ml (Amado-Filho et al., 2007; Riul et al., 2009), and obtained the diameter using a calliper (Steller et al., 2003). Additionally, the sediment and macroalgal species of each rhodolith were separated and dried for 72h in a stove set to 60°C. Later, we weighed each sample on an analytical balance (0.001g). The rhodolith density from the euphotic zone was obtained randomly through 10 photoquadrats of 0.7m² (after Francini-Filho et al., 2013). Each photoquadrat was subdivided into 15 parts that were photographed individually. In the mesophotic zone, we obtained three video transects. Each video has been converted into 40 static images of 0.7m². We used the Coral Point Count software (CPCe) to analyse the images and count rhodoliths (Kohler and Gill, 2006).

Data analysisWe then compared volume, average diameter of rhodoliths, total abundance of macrofauna (i.e. total number of individuals per rhodolith - ind.rhod−1), density of invertebrates per volume of rhodoliths (individuals.cm-3), richness of macrofauna (taxa.rhodolith−1), richness per volume (taxa.cm-3), biomass of macroalgae and weight of sediment between the samples from two depths zones using t-tests. To compare our results with other environments, we standardized our data by multiplying the average of individuals found per rhodolith by the average of rhodoliths per square meter. The relation of macroalgae and sediment trapped was obtained by a simple linear regression between the masses measured to these variables.

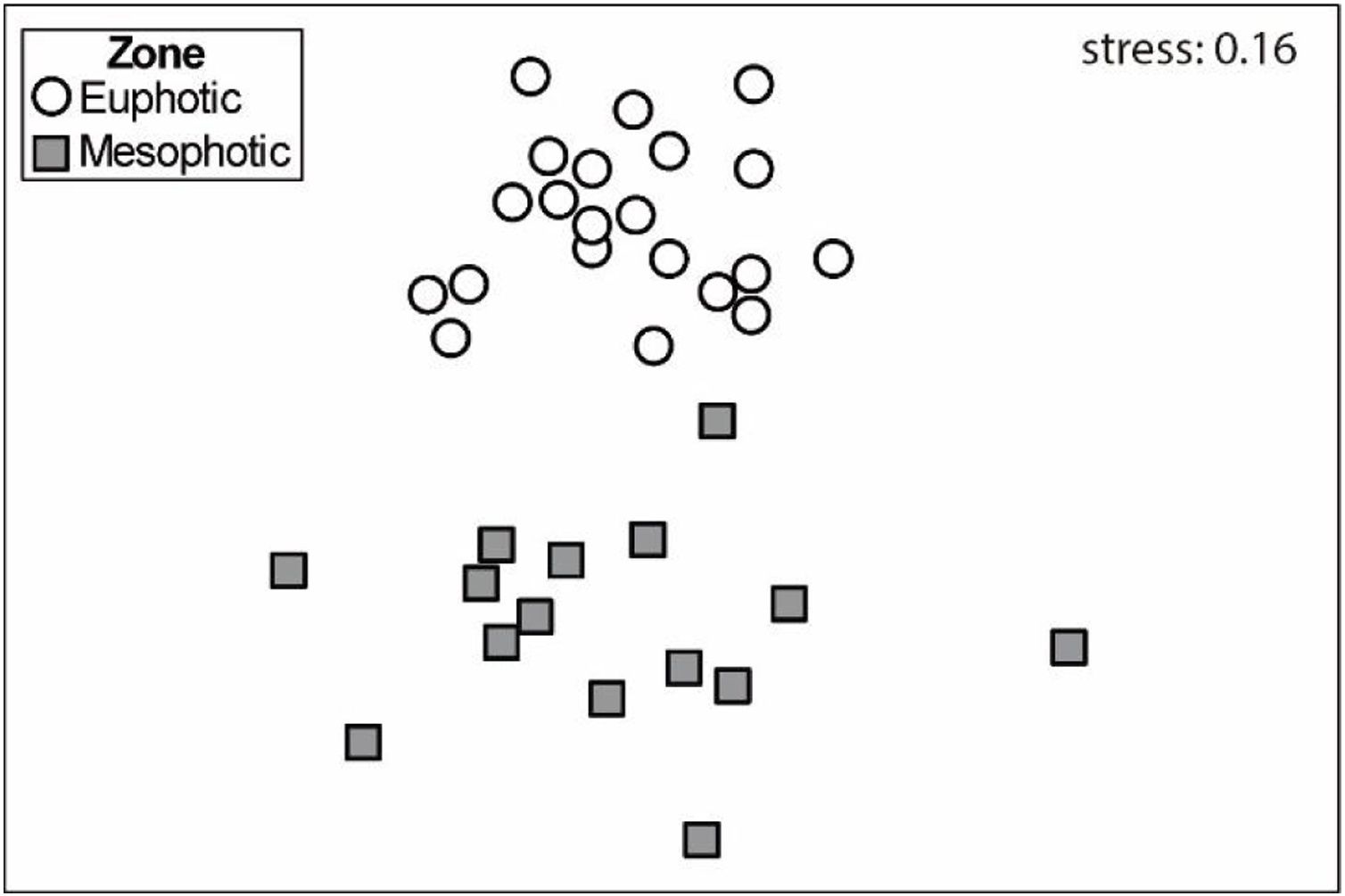

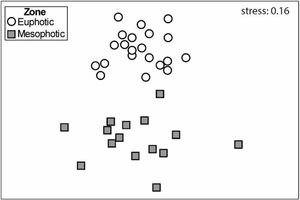

Differences in the community of macroinvertebrates from euphotic and mesophotic zones were tested using an Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) and the results were summarized in the Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS). We used the Bray-Curtis Similarity Index on log(x + 1) transformed abundances (Clarke and Warwick, 2001). Only the most representative taxa (≥0.5 % of total abundance, e.g., Clarke and Warwick, 2001) were considered in the analysis. In addition, a Similarity Percentage analysis (SIMPER) was used to show the main groups contributing to the dissimilarity between the samples obtained at euphotic and mesophotic zones. We also used the Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) to elucidate how the differences in the macrofauna communities from euphotic and mesophotic zones are correlated to the environmental variables. Subsequently, Monte Carlo permutation test (499 permutations) was applied on variables of depth, density of the rhodoliths, fleshy algae biomass, sediment amount, volume and average diameter of rhodoliths to determine which of these variables best explain the patterns found in vagile macrofauna community. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software v.3.5.0 (R Core Development Team, 2018) and Primer v.6.1.13 with Permanova v.1.0.3 extension.

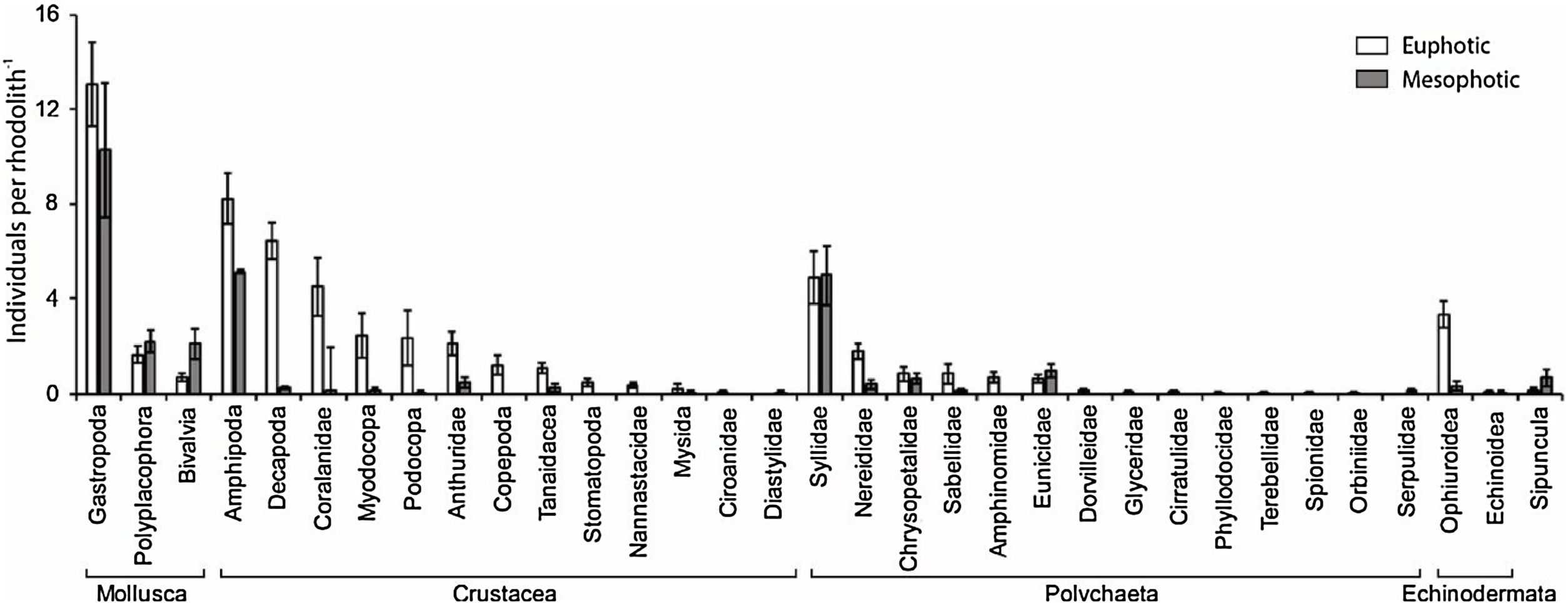

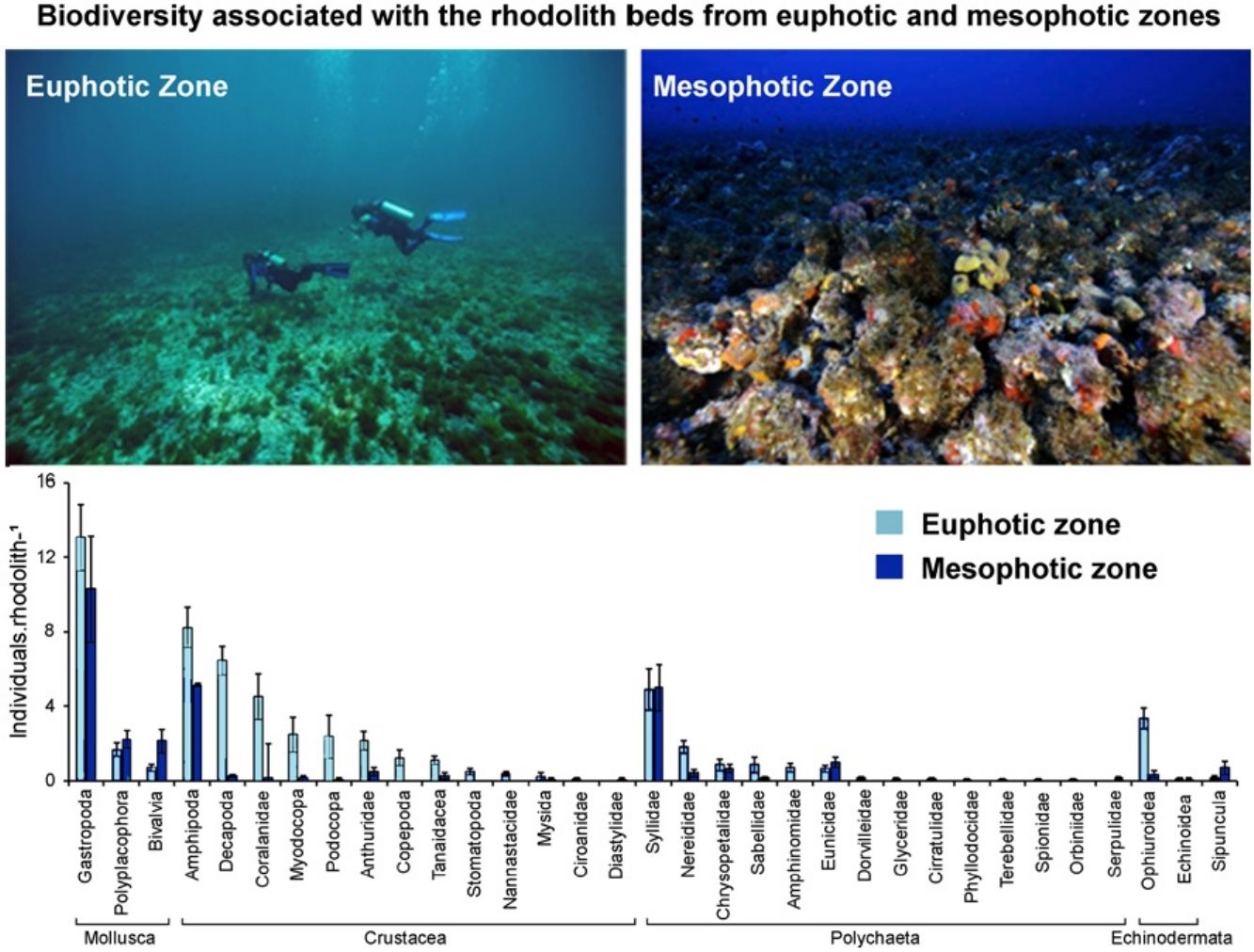

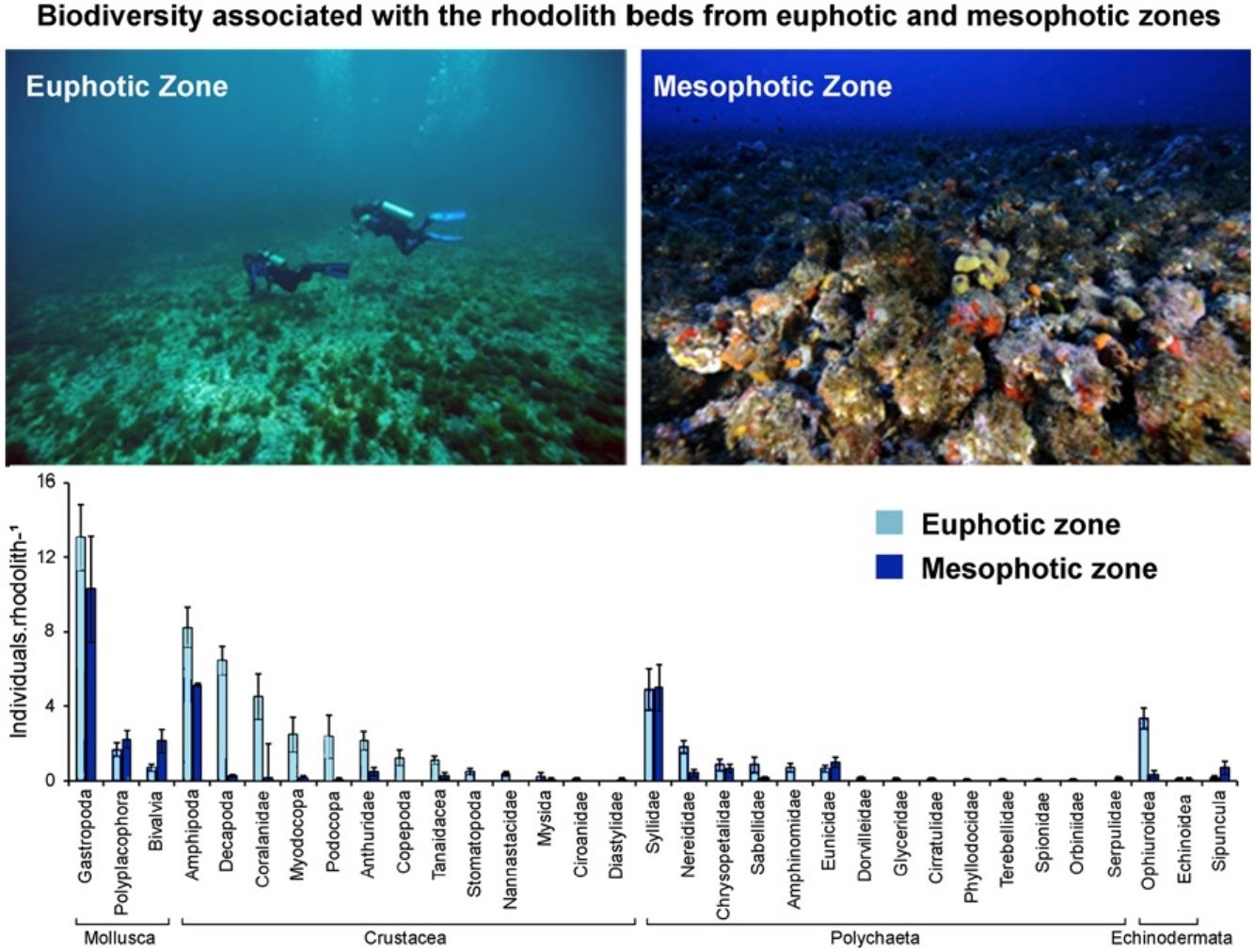

ResultsWe recorded 1661 individuals of vagile macrofauna associated with rhodoliths: 1243 from the euphotic zone and 418 from the mesophotic zone. The most abundant taxa were Gastropoda, Amphipoda, Syllidae and Decapoda (Fig. 2). Rhodoliths from euphotic zone supported more specimens (58.62±5.68in..rhod−1, mean±SE) than those in the mesophotic zone (29.71±5.75in..rhod−1; t=3.44, df=28.9, p<0.01). However, when we standardized the number of specimens by volume of rhodolith, the abundance did not differ between the euphotic (0.50±0.06in.cm-3) and mesophotic zone (0.40±0.06in.cm-3; t=1.15, df=0.10, p=0.27). We also estimated 11,378 individuals per square meter in the euphotic and 9531 from the mesophotic zone.

The average number of taxa per rhodolith was higher in euphotic zone (15.19±0.75 taxa.rhod−1) than in mesophotic zone (8.92±0.71 taxa.rhod−1; t=5.76, df=6.26, p<0.001). In the same way as occurs with abundance, standardization by volume removes the differences in the richness between euphotic zone (0.14±0.02 taxa.cm-3) and mesophotic zone (0.14±0.03 taxa.cm-3; t=0.06, df=0.002, p=0.96). Nineteen taxa were exclusive on rhodoliths from mesophotic zone, most of them Gastropoda, while sixteen taxa were found only on rhodoliths from euphotic zone (Table S1).

Macroinvertebrate community in both depth zones were distinct (Fig. 3; ANOSIM, R=0.37; p=0.001). Between groups dissimilarity observed was 59.8 %, while the within groups similarity values were 52.5 % and 43 % to euphotic and mesophotic zones, respectively. The taxa that most contributed to the dissimilarity were Gastropoda and Amphipoda (21.4 % and 15.6 %, respectively). Gastropoda was also the group that most contributed to within groups similarities (24.2 % and 32.1 % to euphotic and mesophotic zones, respectively), followed by Amphipoda (17.1 %) and Phyllodocida (16.4 %) in euphotic zone and Phyllodocida (31.8 %) and Amphipoda (12.8 %) in mesophotic zone.

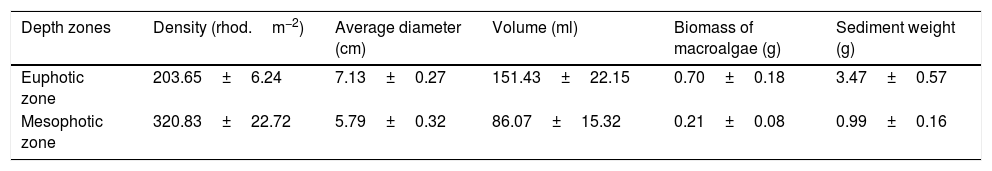

Rhodoliths obtained from euphotic zone presented the highest volume (151.43±22.15ml) and diameter values (7.13±0.27cm) than those found in the mesophotic zone (86.07±15.32ml and 5.79±0.32cm; t=2.43, df=65.36, p=0.02 and t=3.16, df=1.35, p=0.003, respectively; Table 1). In contrast, we observed 1.6x more rhodoliths covering the same area (i.e. 1m2) to mesophotic zone (320.83±22.72 rhod.m−2) than to euphotic zone (203.65±6.24 rhod.m−2; Table 1).

Density of rhodoliths, average diameter, volume, biomass of macroalgae and weight of sediment (mean±SE) between the samples from the two depth zones.

| Depth zones | Density (rhod.m−2) | Average diameter (cm) | Volume (ml) | Biomass of macroalgae (g) | Sediment weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euphotic zone | 203.65±6.24 | 7.13±0.27 | 151.43±22.15 | 0.70±0.18 | 3.47±0.57 |

| Mesophotic zone | 320.83±22.72 | 5.79±0.32 | 86.07±15.32 | 0.21±0.08 | 0.99±0.16 |

The biomass of macroalgae differed between depth zones (t=2.47, df=0.49, p=0.02), decreasing 3-fold from 0.70±0.18g euphotic zone, to 0.21±0.08g.rhod−1 in mesophotic zone. A similar pattern was verified to weight of sediment (t=4.16, df=2.48, p<0.01), decreasing 6-fold from 3.47±0.57g to 0.99±0.16g.rhod−1. The values reflect the dependence between these variables (F=18.07, p<0.001, r2=0.33), i.e, the increase in the coverage macroalgae determines the addition of trapped sediment.

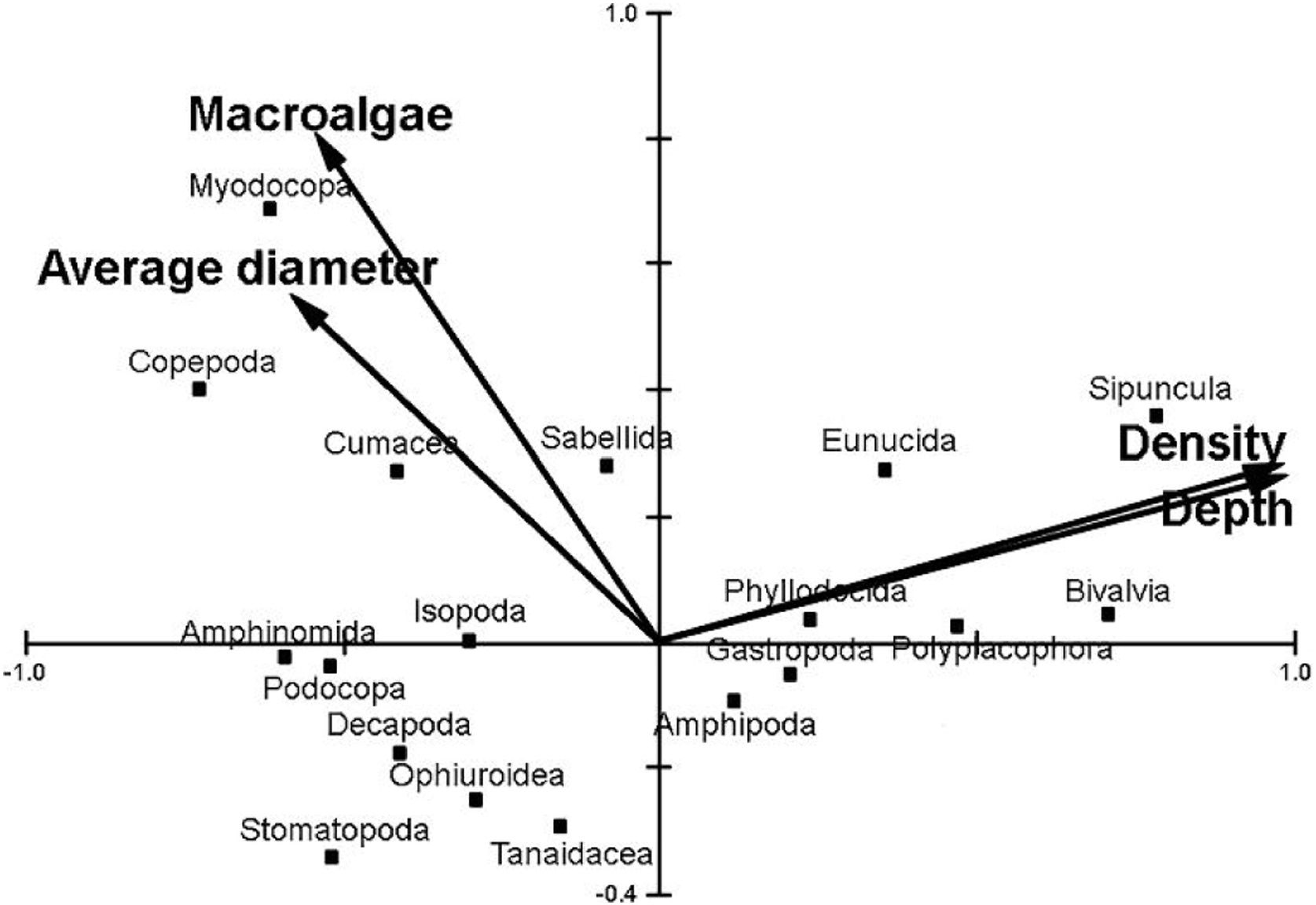

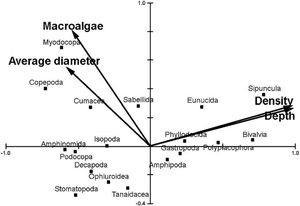

Depth zone, fleshy algae amount, average diameter and density of the rhodoliths were significant in predicting the macrofauna community associated (Monte Carlo Permutation test, p<0.05; Fig. 4). Density and depth zone were important in determining the patterns found for Sipuncula and Bivalvia, but Crustacea seems to be little influenced by these variables. Nevertheless, biomass of macroalgae and average diameter of the rhodoliths are apparently important for increasing the abundance of Myodocopa and Copepoda. Furthermore, the first two axes of the CCA explained 85 % of the macrofaunal community data.

Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) of vagile macroinvertebrates associated with rhodoliths from euphotic and mesophotic zone in the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago. The two axes explain 85 % of the variance of the data. Only average diameter, depth, biomass of macroalgae and density of rhodoliths in the bed were responsible for the observed pattern.

Our results revealed that rhodolith beds from the euphotic zone support twice the abundance of organisms and number of taxa than mesophotic zone, but such difference does not reflect when compared by rhodolith volume. Depth zones also show dissimilarity at community level, suggesting that both environments are ecologically distinct. Literature about diversity of organisms associated with rhodolith beds are major focused in euphotic zone, the association in mesophotic zone is scarce (e.g., Simon et al., 2016; Meirelles et al., 2015; Brasileiro et al., 2016). However, rhodolith beds are found mainly in the mesophotic zone (Bosence, 1983; Littler et al., 1991; Foster, 2001) where they often superpose areas of interest to oil and gas drilling (Moura et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2016; Amado-Filho et al., 2017). Tamega et al. (2013) performed one of the few studies concerning macroinvertebrates associated with mesophotic rhodolith beds in the SW Atlantic. They recorded 76 species of macrofauna (including sessile ones), 17 belonging to Crustacea and six species to Polychaeta. When contrasted with our results, and with higher number of taxa found in the euphotic zone (e.g., Metri, 2006; Bouzon and Freire, 2007; Riul, 2007; Berlandi et al., 2012) the biodiversity associated with the SW Atlantic mesophotic rhodolith beds seems to be much higher as previous works had shown.

By comparing the literature, we verified that macroinvertebrate diversity and abundance found on rhodolith beds are similar or higher than those recorded in other structurally complex environments such rocky shores, seagrass and coral reefs (Table S2). These findings corroborate previous comparisons of diversity associated with rhodolith beds, which on local scales may harbor higher diversity than its adjacent environments (Steller et al., 2003; Hinojosa-Arango et al., 2014). Comparisons with other SW Atlantic rhodolith beds show compositional variations among sites. For example, we recorded 47 taxa of Polychaeta belonging to 9 families while Riul (2007) registered 34 families in a rhodolith bed in the northeastern Brazilian continental shelf, and Metri (2006) and Berlandi et al. (2012) observed 19 and 26 families, respectively. For Crustacea, we recorded nine orders while Riul (2007) pointed five orders of Crustacea (more comparisons are available in Table S2). However, comparisons among different studies and environments should be made critically, for different sampling tools were used and different sampling efforts were undertaken; the size of the observed organisms, the taxonomic resolution achieved, and scarcity of data concerning other oceanic rhodolith beds associated diversity are the main difficulties when comparing data. For instance, Tamega et al. (2013) adopted Van Veen Grab and dredged to sample the macroinvertebrates. These methods should be used with caution when sampling small organisms, especially the soft-bodied, cryptic and infaunal species (Kenchington and Hutchings, 2012; Santos et al., 2016). The use of diving techniques, on the other hand, allows careful individual sampling of each rhodolith, making it more suitable to preserve taxonomic characteristics of the specimens, and maintaining the data of structure and composition of communities (e.g., Pereira-Filho et al., 2012; Moura et al., 2013; Amado-Filho et al., 2016). A drawback of this approach is that the use of diving techniques to sample shallow and mesophotic rhodolith beds is more time-consuming and expensive than dredge sampling.

Worldwide rhodolith beds have been frequently mapped in areas of economic interest, thus they are threatened by many local anthropogenic factors such as overfishing, trawling, directly exploitation of CaCO3, and oil/gas drilling (Steller et al., 2003; Moura et al., 2013; Gondim et al., 2014; Amado-Filho et al., 2017). The effects of latter on large extensive SW Atlantic rhodolith beds are even more unknown than their associated communities. Thus, predicting priority areas for conservation is an emerging need that demands immediate attention (Santos et al., 2016; Amado-Filho et al., 2017). Identifying diversity-predicting variables on rhodolith beds is a discussion that has been ongoing in the current panorama (e.g., Steller et al., 2003; Amado-Filho et al., 2010; McConnico et al., 2014; Teichert, 2014; Santos et al., 2016). Here, we found that four of the six tested variables predicted 85 % of the variability observed in the vagile macroinvertebrate community (i.e. average diameter, depth, biomass of macroalgae and density of rhodoliths in the bed). Thus, these variables should be taken into account in the next research steps in modeling the biodiversity associated with rhodolith beds, especially in the SW Atlantic where mining and rhodolith beds are superposed (Moura et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2016; Amado-Filho et al., 2017). In addition, new experimental approaches are needed to better understand of the synergic effects among the predictive variables of macroinvertebrates associated with rhodoliths. For example, the increase in volume and diameter are negatively related to the rhodoliths density, which makes a greater aggregation of individuals per unit area possible (Bahia et al., 2010). The rhodoliths’ dimensions may also increase the complexity of the environment and, consequently, provide more available colonization areas for macroalgae and sessile organisms (Hinojosa-Arango and Riosmena-Rodríguez, 2004). The depth may also indirectly interfere with the algal biomass due to the reduction of the light incidence and of the photosynthetic rates (Riul et al., 2009; Amado-Filho et al., 2010), as well as directly, by the interference in the rhodolith size by modulating the growth rate (Bahia et al., 2010). In addition, macroalgae may trap sediment in its thallus resulting in a direct relationship between both variables (Smith et al., 2001; Belliveau and Paul, 2002; Stamski and Field, 2006). Besides the complex network and the difficulty to understand the individual effect of each of these variables on the composition and structure of the macrofauna, studies have suggested other predictors of diversity, such as porosity (Teichert, 2014), branching density, rhodolith age (McConnico et al., 2014), thallus volume (Steller et al., 2003) and presence of bioengineers (Pereira-Filho et al., 2015b). Further studies considering large scale modeling are recommended to test the potential of the variables pointed here as predicton of areas harbouring higher values of associated diversity with rhodolith beds. Although knowledge of rhodolith beds is in its infancy, studies have reinforced the ecological importance of this ecosystem (Amado-Filho et al., 2012, 2017; Foster et al., 2013). Rhodolith beds must to be considered as priority sites in conservation and management strategies. Long-term monitoring programs in both euphotic and mesophotic rhodolith beds are essential to improve our understanding and accompany ecological conditions of this important ecosystem, providing data to subside management.

Finally, we observed that less abundant taxa also responded to the same variables. For example, Cumacea, Stomatopoda and Amphinomida were more related to lower values of depth and density, while Sipuncula were present in deeper and denser sites. Even in a more taxonomically refined data, measured variables significantly influenced both abundant and rare taxa. In conclusion, our results show that all variables studied (i.e., volume, diameter, density, depth, macroalgae and sediment) are direct or indirectly influencing the associated biodiversity and should be used in efforts to classify rhodolith beds in conservation policies. However, methods to increase accuracy, speed and resolution of species identification are claimed to better comprehension of the biodiversity associated with extensive marine habitats such as SW Atlantic rhodolith beds. While new scientific advances to better define priority areas for conservation are not completely developed in large geographical scales, the Precautionary Principle in biodiversity conservation and natural resources management (Cooney, 2004) must be adopted to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem services provided by rhodolith beds. As the Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development stated, the lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent potential environmental degradation, such as the growing mining pressures on the poorly known rhodolith beds.

Declaration of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We thank the Fernando de Noronha Marine National Park for the license to survey and collect samples in the archipelago (SISBIO/34245-3). GHPF acknowledges the grant 2016/14017-0, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). GMAF, RLM and GHPF acknowledge individual grants from the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq). VJG acknowledge individual grant 2017/22273-0, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). We also thank Zaira Matheus for field support and Mutue T. Fujii, Luiz F. Netto, Aramys R. M. Cesar, Amanda T. da Silva, and Izabela F. Paes for help taxonomic identifications (macroalgae, Echinodermata and Mollusca). Finally, we thank the comments provided by HT Pinheiro and another anonymous referee.