In Brazil, the introduction of non-native fish is commonplace, and the only existing measure to address this problem is the normative approach (i.e., laws and inspections). However, this approach has failed to control or prevent introductions because enforcing laws in a country the size of a continent, where inspections and monitoring are minimal or non-existent, is difficult. In addition, society is generally unaware of this issue. More effective actions or complementary preventive measures are urgently needed, and the most promising approach is to change human behavior via educational opportunities. In this short essay, we propose that exposing society to high quality information is a powerful alternative because well-informed people naturally make more rational and balanced decisions. For example, informed stakeholders may be more cautious when handling non-native species, may adopt appropriate management practices and may cease deliberate releases. Moreover, a well-informed society will naturally avoid or prevent harmful activities that may lead to the introduction of alien species. From this perspective, this short essay explores opportunities to implement educational practices for containing new introductions. First, we present the primary activities that are responsible for the introduction of non-native fish in Brazil (i.e., aquaculture, fishkeeping and sport fishing) and then suggest simple educational pathways that are specific to each activity. In addition, we advocate for the inclusion of invasion biology in formal education to educate society as a whole. If the topic receives the necessary attention in the educational curriculum, then education will play a central role in creating new behavioral standards, awareness and responsibility at different societal levels, with the primary goal of reducing the rate of new fish introductions.

The introduction of non-native fish has become extremely common in Brazil (Lima Junior et al., 2012; Pelicice et al., 2014). Although several studies have reported negative impacts (e.g., Agostinho et al., 2007; Latini and Petrere, 2004; Figueredo and Giani, 2005; Pinto-Coelho et al., 2008; Pelicice and Agostinho, 2009; Attayde et al., 2011), authorities have made few efforts to prevent new introductions. These introductions are a matter of considerable concern because disruptions to native biodiversity tend to be more difficult to detect and to mitigate in mega-diverse countries (Vitule, 2009; Lövei et al., 2012) such as Brazil. Moreover, the Amazon basin, which is the home of the richest biodiversity of freshwater fish in the world, remains relatively unaffected by the invasion of non-native fish; however, this status may change with the construction of dams and fish farms in the primary tributaries of this basin (e.g., Tocantins, Xingú, Madeira, and Tapajós).

Fish introductions are widespread in Brazil because coercive norms are the only methods that are used to deter introductions (Alves et al., 2007; Agostinho et al., 2007) and because inspections and monitoring are minimal to non-existent. The primary laws that address the introduction of non-native fish are 5197/67 and 9605/98, which prohibit the release of non-native organisms. The first law establishes that: “No species can be introduced into the country without a favorable official report and a license issued according to the law” (“Nenhuma espécie poderá ser introduzida no País, sem parecer técnico oficial favorável e licença expedida na forma da Lei”). Law 9605/98 establishes criminal sanctions for those individuals who “introduce an animal specimen into the country without a favorable technical decision and a license issued by the competent authority” (“Introduzir espécime animal no País, sem parecer técnico oficial favorável e licença expedida por autoridade competente”). The ineffectiveness of the normative approach stems from the difficulty in enforcing the laws because these inspections must cover a country that is the size of a continent. We must consider also that some routes are difficult to regulate (e.g., accidental escapes; Hulme et al., 2008). In addition, these laws explicitly prohibit introductions but leave room for re-interpretation, particularly regarding legal definitions (see Agostinho et al., 2007; Alves et al., 2007); for example, the term “native” has multiple meanings (Agostinho et al., 2006). Moreover, proposals to change these regulations to facilitate the use of non-native fish for aquaculture (Pelicice et al., 2014) are fueled by current policies that are aimed at short-term economic gains. Given this situation, the tools to prevent the introduction of non-native fish in Brazil (i.e., laws and inspections) have little effect, and uncontrolled fish introductions in Brazil are not surprising.

Laws are necessary to regulate the use of non-native resources in countries (Hulme et al., 2008; Roy et al., 2014). However, the normative approach alone cannot prevent the torrent of new introductions occurring in Brazil. More effective actions or complementary preventive measures are urgently needed. Exposing society to high quality information is a powerful alternative (Vitule, 2009; Speziale et al., 2012); well-informed people naturally make more rational and balanced decisions. Education establishes new behavioral standards and awareness, and creates new perspectives regarding a problem. In turn, this education profoundly changes the attitudes and routines of stakeholders. For example, informed stakeholders may be more cautious when handling non-native species, may adopt appropriate management practices and may cease deliberate releases. Moreover, a well-informed society will naturally avoid or minimize harmful activities that may lead to the introduction of alien species. A lack of awareness regarding invasion biology is usually the underlying cause behind deliberate and accidental introductions (Agostinho et al., 2007; Vitule, 2009; Speziale et al., 2012). However, despite the more permanent and internalized results and the wide range of options for implementing educational measures, no official Brazilian programs or incentives exist for establishing strategies with the specific aim of developing environmentally responsible practices for reducing fish introductions. One such approach with preventive and lasting effects and with medium- to long-term results would complement the traditional normative approach, necessary to regulate the trade and use of non-native fish.

Given the current situation, this article explores opportunities to implement educational practices for preventing new introductions. First, we present the primary activities that are responsible for the introduction of non-native fish in Brazil (i.e., aquaculture, fishkeeping and sport fishing) and then suggest simple educational pathways that are specific to each activity. In addition, we recommend educating society as a whole by including invasion biology in formal education. If implemented, these educational actions may produce novel attitudes for coping with non-native organisms, with the primary goal of reducing the rate of new fish introductions to a constant low level.

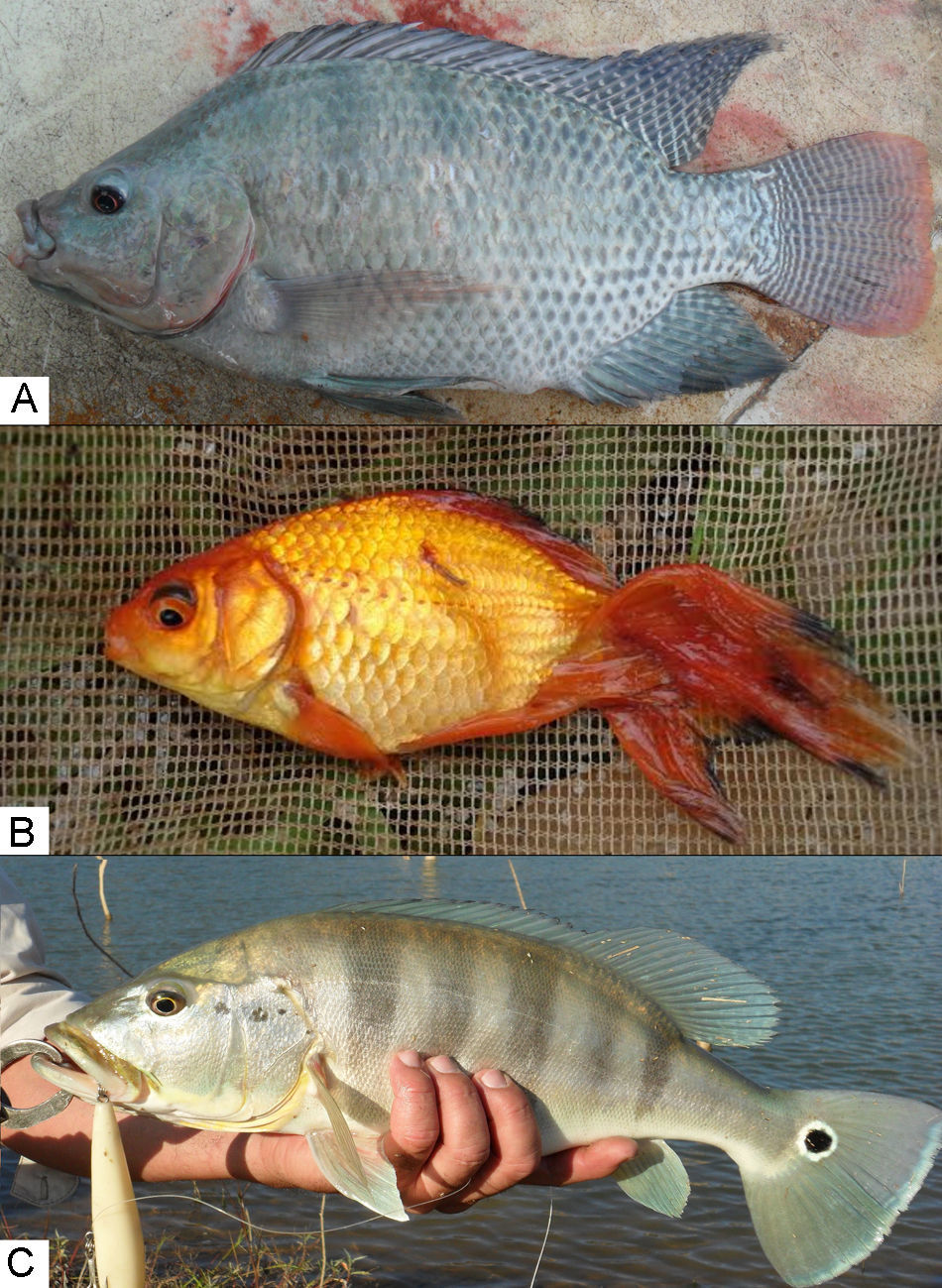

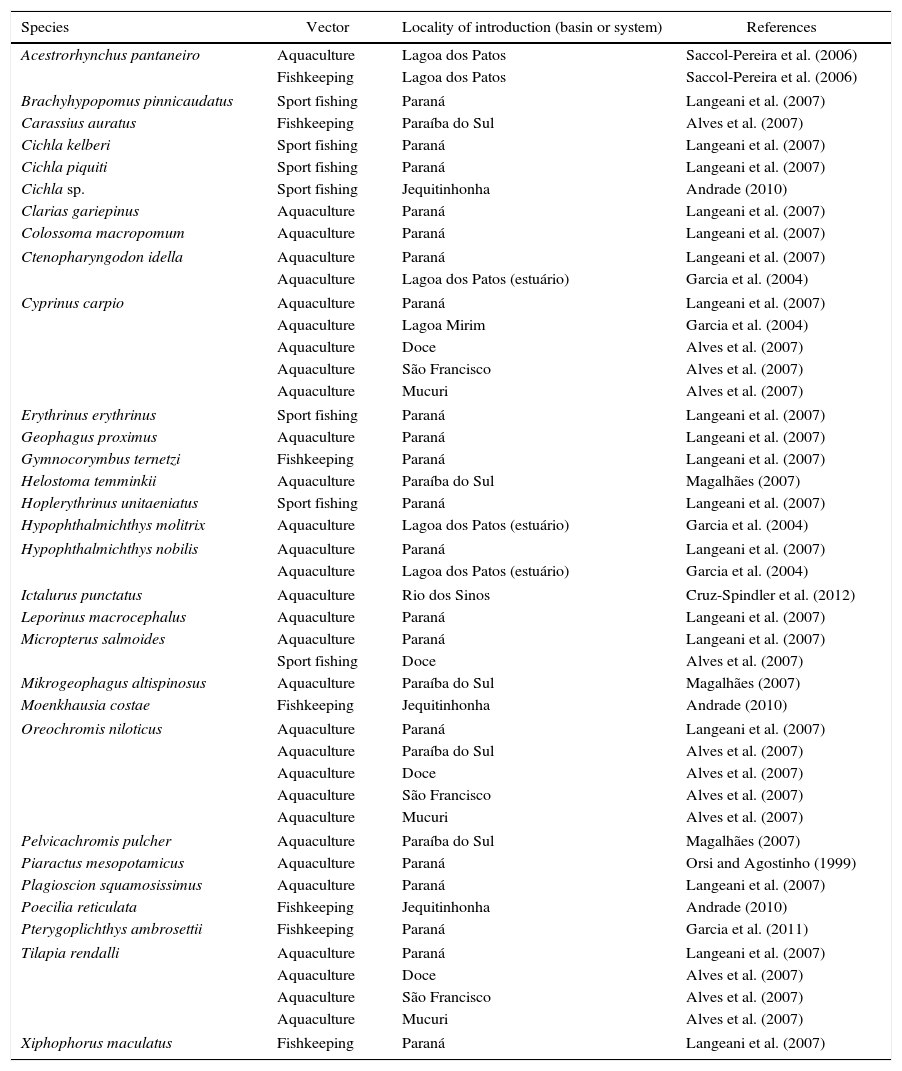

Primary pathways of fish introductionsMost fish introductions in Brazilian inland waters originate from aquaculture (Orsi and Agostinho, 1999; Azevedo-Santos et al., 2011; Agostinho et al., 2007; Daga et al., 2015; Ortega et al., 2015), aquarium fishkeeping (Langeani et al., 2007; Alves et al., 2007) and sport fishing (Júlio Júnior et al., 2009; Britton and Orsi, 2012). These activities are responsible for the introduction and spread of several species across the country (Table 1) and create high and constant propagule pressure in many basins. This section presents a broad picture of each activity, highlighting the primary species released, pathways of introduction, negative consequences, and features that have compromised the success of the “law and inspection” approach.

Examples of non-native fish introduced to different Brazilian freshwater ecosystems via aquaculture (food production or ornamental), fishkeeping and sport fishing (stocking or bait releases).

| Species | Vector | Locality of introduction (basin or system) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acestrorhynchus pantaneiro | Aquaculture | Lagoa dos Patos | Saccol-Pereira et al. (2006) |

| Fishkeeping | Lagoa dos Patos | Saccol-Pereira et al. (2006) | |

| Brachyhypopomus pinnicaudatus | Sport fishing | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Carassius auratus | Fishkeeping | Paraíba do Sul | Alves et al. (2007) |

| Cichla kelberi | Sport fishing | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Cichla piquiti | Sport fishing | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Cichla sp. | Sport fishing | Jequitinhonha | Andrade (2010) |

| Clarias gariepinus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Colossoma macropomum | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Aquaculture | Lagoa dos Patos (estuário) | Garcia et al. (2004) | |

| Cyprinus carpio | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Aquaculture | Lagoa Mirim | Garcia et al. (2004) | |

| Aquaculture | Doce | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | São Francisco | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | Mucuri | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Erythrinus erythrinus | Sport fishing | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Geophagus proximus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Gymnocorymbus ternetzi | Fishkeeping | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Helostoma temminkii | Aquaculture | Paraíba do Sul | Magalhães (2007) |

| Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus | Sport fishing | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | Aquaculture | Lagoa dos Patos (estuário) | Garcia et al. (2004) |

| Hypophthalmichthys nobilis | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Aquaculture | Lagoa dos Patos (estuário) | Garcia et al. (2004) | |

| Ictalurus punctatus | Aquaculture | Rio dos Sinos | Cruz-Spindler et al. (2012) |

| Leporinus macrocephalus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Micropterus salmoides | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Sport fishing | Doce | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Mikrogeophagus altispinosus | Aquaculture | Paraíba do Sul | Magalhães (2007) |

| Moenkhausia costae | Fishkeeping | Jequitinhonha | Andrade (2010) |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Aquaculture | Paraíba do Sul | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | Doce | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | São Francisco | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | Mucuri | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Pelvicachromis pulcher | Aquaculture | Paraíba do Sul | Magalhães (2007) |

| Piaractus mesopotamicus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Orsi and Agostinho (1999) |

| Plagioscion squamosissimus | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Poecilia reticulata | Fishkeeping | Jequitinhonha | Andrade (2010) |

| Pterygoplichthys ambrosettii | Fishkeeping | Paraná | Garcia et al. (2011) |

| Tilapia rendalli | Aquaculture | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

| Aquaculture | Doce | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | São Francisco | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Aquaculture | Mucuri | Alves et al. (2007) | |

| Xiphophorus maculatus | Fishkeeping | Paraná | Langeani et al. (2007) |

This activity is the primary source of non-native species around the world (Naylor et al., 2001). In Brazil, aquaculture has also played a role and has resulted in the introductions of several species of fish (Orsi and Agostinho, 1999; Agostinho et al., 2007; Azevedo-Santos et al., 2011; Ortega et al., 2015) and other organisms (Paschoal et al., 2013). With current governmental incentives to develop aquaculture in Brazil (Pelicice et al., 2014), invasions due to aquaculture are likely to increase.

Many studies have mentioned or reported fish introductions via aquaculture. For example, Orsi and Agostinho (1999) reported massive fish escapes in the middle Paranapanema River, which involved more than a million individuals from eleven non-native species. Azevedo-Santos et al. (2011) reported regular escapes of Nile tilapia (Fig. 1) from net cages installed in the Furnas Reservoir, Grande River, Upper Paraná basin. The authors verified that these fish culture systems are an important pathway for fish introductions and emphasized that farmers should receive technical support to improve management and prevent escapes. Magalhães (2007) and Magalhães and Jacobi (2013a) reported the presence of several non-native ornamental fish in natural streams located near fish farms, showing that escapes are routine.

The preference of farmers for non-native fish and hybrids is an important contributor to aquaculture as a continuing source of invasions. This preference has been institutionalized in the recent Proposed Law 5.989/09 that “naturalized” some non-native fishes (carps and tilapia) as a strategy to stimulate fish farming (see Lima Junior et al., 2012; Vitule et al., 2012; Pelicice et al., 2014). Similarly, a normative regulation (No. 16/2014) supported by the Ministry of Fishing and Aquaculture facilitates the farming of fish from the Amazon Basin and other regions for ornamental purposes (Vitule et al., 2014). The problem worsens with inadequate management at aquaculture farms, such as the lack of effective confinement, negligence and inadequate practices (e.g., tank cleaning). Acquiring the fry of thousands of non-native species that are produced and sold across Brazil with little or no control or inspection is simple and easy. Thousands of small commercial and subsistence farms, including fishing ponds (Fernandes et al., 2003), are spread across the country. Most are located along the periphery of cities and rural areas, without authorization from local authorities; the inspection of these properties is unlikely. Moreover, controlling the processes of each producer, many of whom are completely unaware of the problems caused by invasions, is extremely difficult.

FishkeepingOrnamental fishkeeping is a growing hobby in Brazil, with a huge potential for the introduction of non-native fish (Magalhães and Jacobi, 2013b; Magalhães and Vitule, 2013) and other organisms (Assis et al., 2014). In fact, several fish species were introduced in Brazil via ornamental pet dumping (Table 1).

Most introductions related to fishkeeping occur through the action of hobbyists who are generally motivated by ethical and sentimental concerns. In some situations, these hobbyists want to dispose of their fish for one or more of the following reasons: (i) the species is too aggressive, (ii) the species grows excessively, (iii) the species is extremely prolific, or (iv) aquarium maintenance demands too much time and effort (Magalhães and Jacobi, 2013b). Hobbyists usually dump their pets into lakes, streams, rivers or reservoirs to prevent death or injury (Agostinho et al., 2006; Magalhães and Jacobi, 2013b).

Currently, fish from any zoogeographical region can be purchased in aquarium pet shops and on the Internet. In large cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, non-native species, including fish from the Amazon basin, Australia, South Asia and Africa, are sold with no restrictions. Even forbidden species such as the giant snakehead Channa micropeltes are readily available (Magalhães and Vitule, 2013; Magalhães, 2015). Large species such as redtail catfish (Phractocephalus hemioliopterus) and alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula) are also easily obtained in the market (A.L.B. Magalhães, personal observation). Consumers do not receive any instructions regarding how to proceed when pets become undesirable; thus, dumping in natural areas is common. Obviously, deliberate releases cannot be inspected or controlled because these releases are casual, diffuse and unpredictable.

Sport fishingInitiatives to stock non-native species for sport fishing are extremely common, albeit illegal, and have been conducted by fishing clubs and by anglers. Furthermore, sport fishing and the catch-and-release of non-native species are increasingly popular in Brazil and may possibly stimulate translocations between basins. Several species, particularly large predators, have been introduced by sport fishing (Table 1). A representative example is the introduction of trout into Brazilian rivers and streams (Agostinho et al., 2006; Vitule, 2009). Other examples include voracious predators such as the black bass (Micropterus salmoides) and several species of peacock bass (Cichla spp.) that have disseminated through many hydrographic basins and hydroelectric reservoirs. The discarding of live bait is another issue that includes non-native species (Table 1) such as “knifefish” (e.g., Gymnotus spp.) and “aimara” (e.g., Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus) (Langeani et al., 2007; Júlio Júnior et al., 2009).

As with aquaculture, a lack of information regarding invasion biology is the norm among anglers and associated stakeholders. For example, existing legislation promotes ambivalence. Municipal laws exist that protect non-native species for fishing purposes. Municipal Law N°. 1718 2013 allows the catch-and-release of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in the Crioulas River, Santa Catarina. This state, together with Rio Grande do Sul, is part of the Trout Route, which is a tourist fishing trip in south Brazil. Cases in which different stakeholders engage to preserve an invader also exist. For instance, fishing for peacock bass (Cichla spp.) in reservoirs in the Paraná River Basin has supported tourism activities. Consequently, multiple sectors (sport and traditional fishermen, authorities, and the hotel industry) have demanded conservation actions to preserve the fish stock, e.g., catch-and-release and juvenile preservation. An aggravating factor is the role played by the media, which commonly associates the catch-and-release of non-native fish with environmentalism (Vitule, 2009). Anglers usually think similarly; some sport fishing associations have canceled their tournaments when notified that they could not release the captured fish, although official environmental agencies have promoted the capture and removal of invaders. Sometimes anglers keep the native fish for consumption and release invaders that are valued for sport fishing (A.A. Agostinho, personal observation).

As with fishkeeping, foreseeing where anglers will introduce new species is virtually impossible. Anglers are usually well organized and promote clandestine fish stocking; thus, the detection of this activity is difficult or impossible. The juveniles and adults of many species are sold unrestricted across the country, and the acquisition and release of hundreds or thousands of young fish into any stream or reservoir in the country without the knowledge of authorities are extremely easy.

In summary, these three activities account for most non-native fish introductions in Brazil, and the only existing preventive measure is the normative approach (laws and inspections). However, the following reasons indicate that this approach is doomed to failure: (i) the number of inspectors is low; (ii) accidental or deliberate fish introductions are casual events that cannot be predicted, and catching offenders and applying penalties are extremely difficult; (iii) Brazil is geographically extensive, with millions of water courses that are distributed in different basins, including many in remote areas that will never be inspected; and (iv) neotropical fish fauna exhibits complex biogeographical patterns within and between basins. Thus, specialized knowledge is required to determine the “native” status of any species, and inspectors lack this knowledge. Considering that we live in an economically oriented world that is globalized in terms of trade, communication and transportation, hundreds of non-native organisms, including fish, will inevitably be transferred between different basins for food production and for other purposes (Hulme, 2009). Therefore, we firmly believe that the problem of freshwater fish invasions must be approached differently.

Educating the vectorsA promising alternative to the current situation in which the introduction of non-native fish is virtually uncontrolled in Brazil is the engagement of civil society. Informed citizens would have the knowledge base to inspect, avoid and rethink risky or harmful activities. Additionally, new introductions will naturally be minimized if the law is voluntarily observed or if people choose precautionary principles. However, people are unaware of specific laws regarding non-native organisms and have little or no information regarding the negative impacts of non-native fish. Ignorance regarding this topic reaches all levels of society, including public authorities, decision makers and laymen (Pelicice et al., 2014). Preventing new introductions will be extremely difficult while this knowledge gap persists.

Actions to inform and educate people must be the primary routes for inducing desirable behavioral changes. Below, we illustrate some simple, vector-specific, educational opportunities that could lead to a decreased flow of non-native fish into natural ecosystems.

AquacultureTraining in aquaculture courses focuses on production and trade, with little or no attention given to environmental issues. Therefore, ecologically based information must reach people who are involved in aquaculture, leading to better management practices in net cages, tanks, hatcheries and fishing ponds. The target audience must be key participants in the production chain, i.e., regulatory and development agencies, fry producers and fish farmers. The key goals for aquaculture should include the following: (i) stopping deliberate releases, (ii) reducing the incidence of accidental escapes, and (iii) fostering the use of native species by presenting viable species (e.g., Kubitza et al., 2007) and by transferring the appropriate technology. These goals could be achieved via specific short-term courses that are fostered by government initiatives or by other agencies (e.g., Table 2) or through the inclusion of this topic in existing aquaculture courses. Authorities, agencies and fish farmers could also attend lectures offered by specialists at universities and research centers. At reservoirs, hydroelectric companies could support aquaculture courses as part of their social and environmental obligations, particularly those companies that are promoting fish farms. Technicians from official agencies (e.g., Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources, IBAMA, and Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, EMBRAPA) should visit aquaculture centers to transfer management protocols. These educational approaches should teach, e.g., sound techniques for safe containment, tank cleaning and fish removal; correct screening practices for sorting juveniles by size and species, preventing the escape of small fish and aggregate species; short- and long-term ecological impacts caused by non-native species; potential economic losses; and technical protocols for raising native species present in the region (i.e., regionalization of aquaculture; Pelicice et al., 2014). These measures may generate fast and effective results because fish escapes cause financial losses to fish farmers.

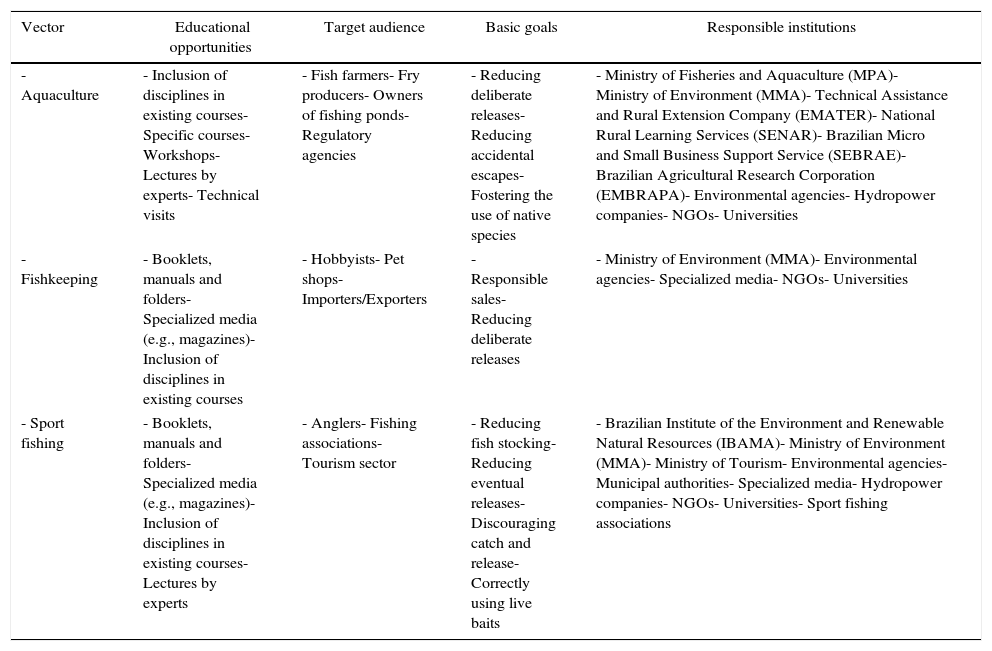

Educational opportunities for preventing the introduction of non-native fish in Brazil. These activities are specific to the three primary vectors in Brazil (aquaculture, fishkeeping and sport fishing), informing the target audience, basic goals and potential institutions that could assume the task.

| Vector | Educational opportunities | Target audience | Basic goals | Responsible institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - Aquaculture | - Inclusion of disciplines in existing courses- Specific courses- Workshops- Lectures by experts- Technical visits | - Fish farmers- Fry producers- Owners of fishing ponds- Regulatory agencies | - Reducing deliberate releases- Reducing accidental escapes- Fostering the use of native species | - Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture (MPA)- Ministry of Environment (MMA)- Technical Assistance and Rural Extension Company (EMATER)- National Rural Learning Services (SENAR)- Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE)- Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA)- Environmental agencies- Hydropower companies- NGOs- Universities |

| - Fishkeeping | - Booklets, manuals and folders- Specialized media (e.g., magazines)- Inclusion of disciplines in existing courses | - Hobbyists- Pet shops- Importers/Exporters | - Responsible sales- Reducing deliberate releases | - Ministry of Environment (MMA)- Environmental agencies- Specialized media- NGOs- Universities |

| - Sport fishing | - Booklets, manuals and folders- Specialized media (e.g., magazines)- Inclusion of disciplines in existing courses- Lectures by experts | - Anglers- Fishing associations- Tourism sector | - Reducing fish stocking- Reducing eventual releases- Discouraging catch and release- Correctly using live baits | - Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA)- Ministry of Environment (MMA)- Ministry of Tourism- Environmental agencies- Municipal authorities- Specialized media- Hydropower companies- NGOs- Universities- Sport fishing associations |

The target audience for this segment should be retailers and fish hobbyists. The key goals for fishkeeping should include the following: (i) encouraging responsible sales by providing technical information about species that are sold and (ii) avoiding deliberate releases from aquarists by teaching correct discarding procedures (Table 2). This strategy would include booklets, handbooks or folders to be distributed among hobbyists in pet shops, particularly when purchasing fish (Fig. 2). These materials should contain ecological information, such as geographical origin, feeding, juvenile and adult body sizes, aggressiveness, historical records of past introductions, invasive potential and environmental and economic risks in the case of introduction. Aquarists should also receive instructions regarding good practices for discarding undesired fish. With the help of governmental agencies and NGOs, efforts should be made to add all of this information to specialized literature (magazines, journals, books and websites). Finally, fishkeeping courses should include sections on biological invasion to educate different stakeholders (importers, distributors, wholesalers, retailers and hobbyists) regarding better management practices. Strategies discussed in the previous section (aquaculture) also apply to this vector.

Example folder with information on species of non-native ornamental fish, in order to instruct aquarist and society in general. Folder reproduced of Garcia et al. (2014).

The target audience should include (i) anglers, (ii) fishing associations and (iii) the tourism industry. The key goals for sport fishing should include the following: (i) stopping or decreasing the rate of eventual releases and clandestine fish stocking, (ii) discouraging catch-and-release of non-native species, and (iii) promoting the correct use of live baits (Table 2). Given the extensive diffusion and influence of TV programs and magazines among anglers, a crucial strategy would be the dissemination of high quality information through these media. Currently, specialized media are completely unaware of the invasion issue and typically associate non-native fish with good fishing opportunities, tourism and leisure. Researchers (e.g., biologists and ecologists) could be invited to write letters and minireviews regularly for these media to fill this gap; the opinion of researchers will certainly familiarize the angler community with the invasion issue. As with the fishkeeping industry, informative booklets, guides and pamphlets must be produced and distributed in fishing stores. The engagement of the tourism sector is also central. Fishing ponds, hotels and tourism guides should receive guidelines for instructing and inspecting anglers, with the support of official authorities (e.g., IBAMA). Another key point is the engagement of sport fishing associations, which have historically played a negative role by stocking non-native fish. This engagement could come from lectures and short-term courses with the support of governmental institutions and universities (Table 2). In fact, the participation of universities and researchers in educating anglers, aquarists and fish farmers must be actively sought and encouraged by authorities.

Educating societyAlthough these activities are the primary sources of non-native fish in Brazil, the problem transcends these activities. Other vectors exist; for example, official fish stocking efforts that introduced several non-native fish species in reservoirs remain an eventual propagule source (Agostinho et al., 2010). Planned releases have also been conducted for biocontrol purposes (e.g., Langeani et al., 2007). In addition, people often consume non-native fish without knowing all the environmental risks and consequences behind the production chain, encouraging the continued development of aquaculture with non-native fish. Therefore, educating society as a whole to enlighten people about this issue is essential and is the only concrete way to create new behavior, awareness and responsibility. Unfortunately, this education is not occurring in Brazil. Few people have the opportunity to learn about biological invasions, and the opportunity exists only in higher education (i.e., university) as a minor topic addressed within a few courses (e.g., biology, ecology) of specific disciplines (e.g., ecology, biological conservation, environmental impact assessment). Thus, the attention that this subject receives in formal education is incompatible with its environmental and economic relevance. Teaching institutions from primary school to higher education should take on the task of changing this situation.

Primary and secondary educationScientific textbooks must address biological invasion issues at all education levels, with continued development and increasing focus and depth. In secondary school, addressing biological invasion as a separate topic to explore its complexity is possible. This subject must also be formally included in environmental education activities, engaging students and teachers with research lectures. Educating people from these early education levels has the greatest transformative potential for molding desirable behavior and for inducing responsibility.

Technical educationAs with primary and secondary education, technical courses in related areas (e.g., environment, agriculture, aquaculture, and tourism) should formally include this subject in the curriculum to qualify technicians to manage production systems responsibly. Some courses are strategies (e.g., aquaculture, tourism) for producing beneficial short-term effects because these technicians work directly with the vectors that promote introductions (e.g., fish farmers and anglers).

Higher educationUndergraduate courses (e.g., agronomy, aquaculture, fishing engineering, biology, ecology, veterinary, and zootechny) must include specific disciplines and research programs regarding biological invasion. Including coursework regarding biological invasion in disciplines that target production should be a priority for producing short-term benefits. Moreover, universities must take responsibility for fostering the use of native biodiversity in aquaculture by developing efficient technologies and by offering profitable options to fish farmers (Vitule et al., 2009; Pelicice et al., 2014). Obviously, graduate programs (Master and PhD) must participate. Actually, some environmentally oriented graduate programs (e.g., ecology, zoology and conservation biology) have a tradition of focusing on biological invasion issues; however, this topic must also be addressed in programs that target production (e.g., aquaculture and fishing engineering). A pioneering experiment has begun in the Aquaculture and Sustainable Development program, Federal University of Paraná (Palotina, Paraná), which is attempting to combine sustainable principles with production aims. Notably, Brazilian research regarding aquaculture is primarily oriented toward non-native species, particularly tilapias and carps. Research avenues for the production of native species can only be developed with the engagement of higher education institutions.

The lack of involvement by biological invasion experts in solving practical problems is another weakness that must be resolved; educational programs can play a major role in the solution to this weakness. In general, Brazilian universities have little involvement with civil society with regard to biological invasions, and many experts have contributed at the foundational level, with theoretical advancements and knowledge production. Special efforts should be made to integrate researchers and society because the former have the knowledge and the ability to ensure better preventive practices, management and eradication. Experts can transfer high quality information to different stakeholders, particularly anglers and fish farmers, clarifying fish introduction pathways, correct management practices and associated risks.

We are convinced that formal education may help incorporate awareness of biological invasion into the societal routine and particularly into the production chain. Education will play a central role in creating new behavioral standards, awareness and responsibility at different societal levels if the issue receives the appropriate attention in educational settings. Thus far, however, this subject has been neglected or absent from textbooks and scholarly curricula.

Final considerationsBiological invasions are a central agent in the current biodiversity crisis. Invasions have affected or compromised the functioning of natural ecosystems, posing a risk to human societies (Spencer et al., 1991; Pimentel et al., 2000; Simberloff et al., 2013). The globalization of trade and communication has made preventing and controlling new introductions extremely difficult because human activities can easily transfer species to different places around the world (Rahel, 2007; Leprieur et al., 2008). In Brazil, the introduction of non-native fish is commonplace, and the only existing measures to address the problem are normative (i.e., laws and inspections). These measures have failed to control, prevent or reduce introduction rates.

Given the current situation, alternatives must be sought and put into practice. Considering the pervasiveness, extent and nature of this problem, the most promising approach is changing human behavior. We are aware that changing the behavior and basic values is a tremendous challenge, but it is the most effective way to create awareness and lead to better practices (Fischer et al., 2012). These goals can only be achieved via education (in any of its forms) and via the dissemination of high quality information to society, specifically to stakeholders that are related to aquaculture, fishkeeping and sport fishing. Because biological invasions are a global problem, educational measures should be promoted at a global scale and involve all societal levels. As long as nations trust only in coercive measures to prevent new introductions and neglect the education of their citizens, organisms will continue to be introduced, and freshwater fish diversity will continue to tend toward homogenization.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank Diego A.Z. Garcia for providing Figure 2. Valter M. Azevedo-Santos received CAPES research grant and Fernando M. Pelicice, Jean R.S. Vitule and Angelo A. Agostinho received CNPq research grants.