Illegal hunting and fishing activities are of great relevance to conservation policies. Few studies with regional focus of the impacts of these activities in Brazil are available. The aim of this study was to characterize illegal hunting and fishing on a national level by collecting data from the environmental police. We analyzed reports prepared by 16 states, all of them which contained a variety of information about seized species, and showed a lack of standardization of data collection and presentation. Illegal fish seizures were predominantly of Amazonian species. Illegal hunting seizures showed the most uniform territorial distribution. Armadillos (Dasypodidae family), pacas (Cuniculus paca), and capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) were the most frequently seized species, and numerous seizures of Brazilian guinea pig (Cavia aperea) were reported in northeastern Brazil. The reports provided by environmental military police have great informative power for conservation policies, but they must be standardized among states to improve the quality of data provided and analysis.

Environmental issues have been routinely discussed by the scientific community and by the whole society. In general, is evident an increasing concern for the expansion of legal environment protection through the establishment of laws that inhibit degrading practices (Velho et al., 2012).

Illegal hunting and fishing activities, in combination with habitat loss, deforestation, and the introduction of exotic species, contribute to biodiversity loss in all Brazilian ecosystems (Tabarelli et al., 2005).

Wild animals, it's body parts and its sub products are widely used by human societies worldwide, mainly as protein source for food and feed, clothing and tools, and for medical, cultural and magical/religious purposes (Alves, 2012). Besides, hunting practices reflect local economic, ecological, cultural, and social aspects of the regions where they occur. These activities play an important role in wildlife population dynamics, mainly in ecosystems with high levels of anthropization and fragmentation, such as the Brazilian rainforest and the Amazon forest (Chiarello, 2000). Together, subsistence hunting and habitat fragmentation may drives to species local extinction (Peres, 2010).

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities are of major concern in aquatic ecosystems, and researchers face great difficulties in collecting data about fish production and capture (FAO, 2014).

Information about the areas and species most threatened by illegal activities, and the impacts of such activities on wild populations, is of great importance for conservation policy establishment. Studies characterizing wildlife hunting activities in Brazil are focused mainly in ethnozoology. There are many descriptions of hunting patterns and its uses in a large variety of Brazilian regions, all of them based on surveys carried out interviewing local residents in northern and northeastern communities of Brazil (Alves and Rosa, 2010; Barbosa et al., 2011; Dantas-Aguiar et al., 2011; Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2013; Souza and Alves, 2014), southeastern region (Hanazaki et al., 2009) and Amazon forest (Lopes et al., 2012; Mesquita and Barreto, 2015). There are also few studies based on official data, provided by governmental entities, all of them with regional focus (Chiarello, 2000; Dias-Junior, 2010; Fuccio et al., 2003; Nogueira-Filho and Nogueira, 2000).

The aim of this study was to collect data about seizures reported by environmental military police in Brazil and to characterize illegal hunting and fishing activities in Brazilian territory with national scope.

Material and methodsFor this study, invitation letters were sent to environmental military police command centers of all Brazilian states. These letters requested all available data from police reports regarding seizures related to illegal hunting and fishing in each jurisdictional area in 2013 and the first half of 2014. For Minas Gerais State, where only online data were available, we searched the online police reports database using the keywords “illegal hunting” and “illegal fishing”. The data were collected from 114 reports in which bushmeat or fish seizures were found.

For data analysis, only information regarding slaughtered carcasses was included. Bushmeat seized from illegal hunting practices was counted in units and fish seizures were counted in kilograms. The data were organized per state and per taxonomic group: fishes and invertebrates for illegal fishing and mammals, birds and reptiles for illegal hunting.

It was evaluated the correlation between seizure numbers and State area. To verify if data are parametric or non-parametric, a normality test was performed, followed by a correlation test. The statistical analyses were done at Sigma Plot software and the information regarding States area was collected on the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics website (IBGE) (http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/geociencias/areaterritorial/principal.shtm).

Collecting data from the military police was a strategy for a national coverage based on their broad operating area, covering almost all Brazilian municipalities.

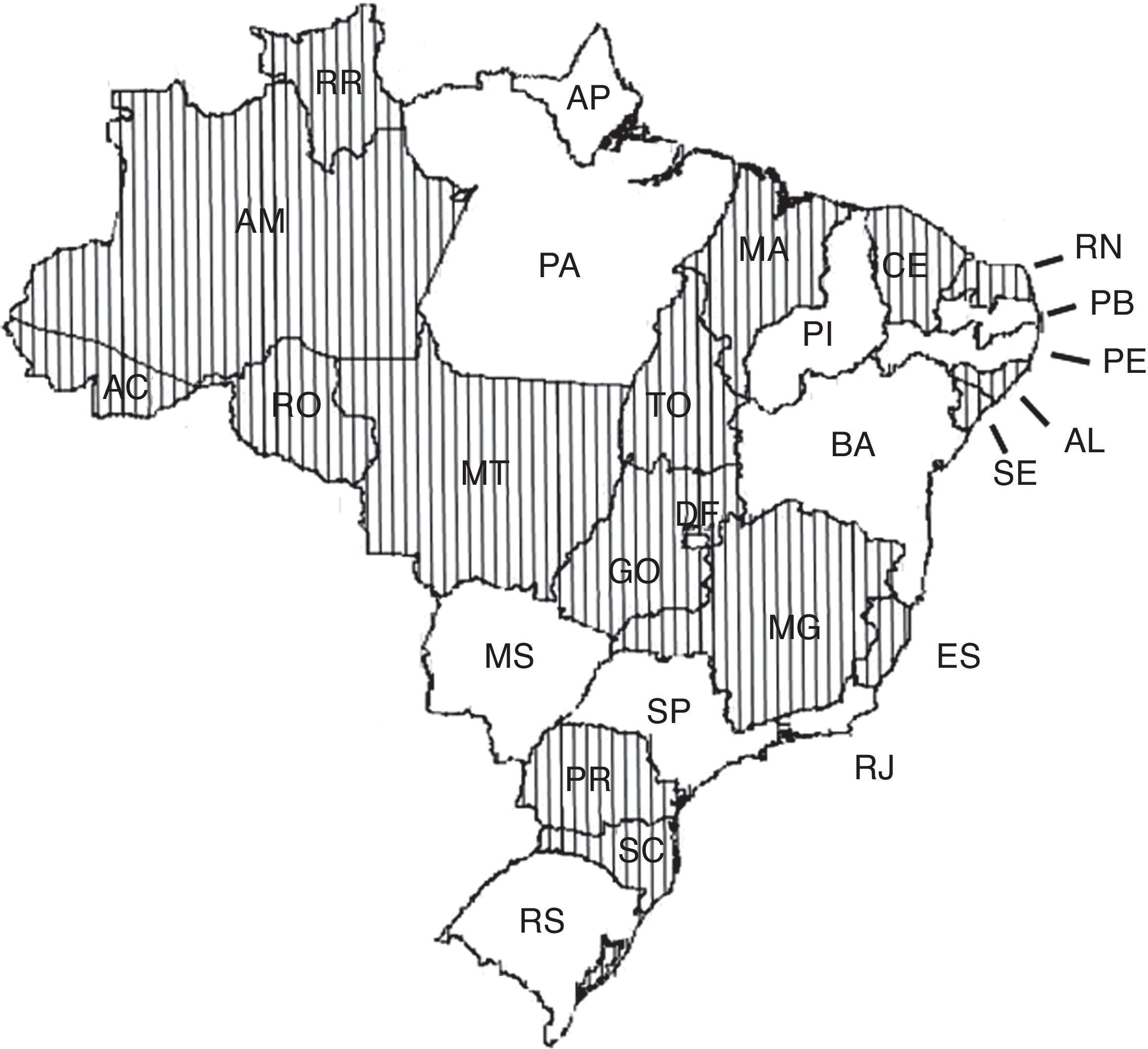

ResultsReports from 16 out of 27 (59%) police commands were analyzed: Acre (AC), Alagoas (AL), Amazonas (AM), Ceará (CE), Espírito Santo (ES), Goiás (GO), Maranhão (MA), Mato Grosso (MT), Minas Gerais (MG), Paraná (PR), Rio Grande do Norte (RN), Rondônia (RO), Roraima (RR), Santa Catarina (SC), Sergipe (SE) and Tocantins (TO) (Fig. 1). The area coverage represents 61.27% of Brazilian territory.

AL, CE, GO, MT and RR sent data only regarding illegal fishing. AC, ES, MA, RN and SE sent data only regarding illegal hunting. The other states have provided collect data of both activities. There was no standardization of the reports produced by each state.

In total, 142,744.70kg of fish and derived products were seized, of which 38,823.88kg (27.2%) were not identified. For all the cases in which identification was performed, the popular names of fish species were used instead scientific names. Table 1 shows the most commonly seized fish species per state.

Fish seizures by species and state,a in kilograms.

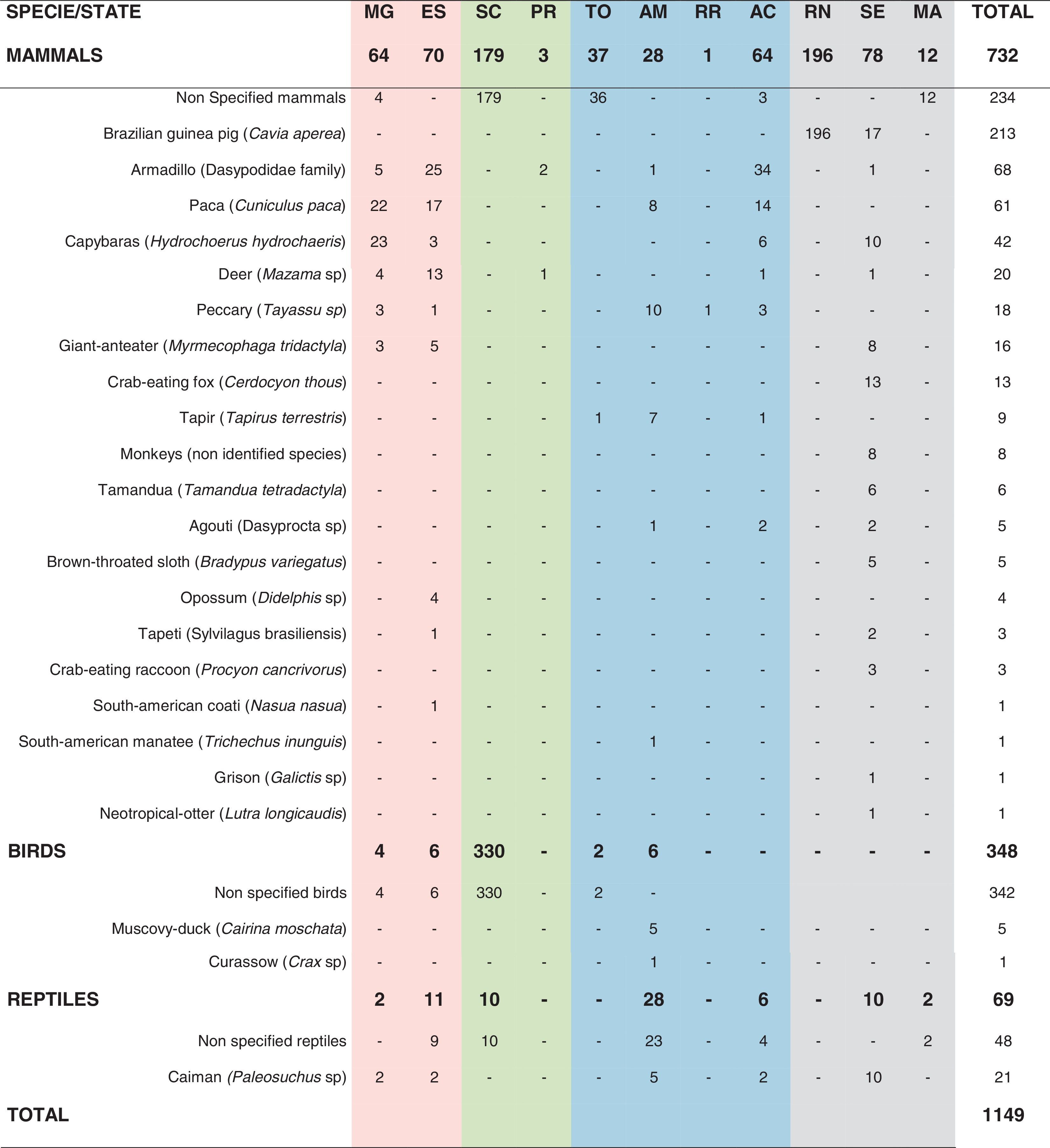

The seizure of 1149 illegally slaughtered animal carcasses was reported: 732 mammals (63.7%), 348 birds (30.3%), and 69 reptiles (6%). Species identification was performed in 525 cases (45.7%), also giving only popular names. Table 2 shows the most commonly seized species.

Bushmeat seizures by species and state,a in units.

Few studies based on Brazilian official data are available. In a survey carried out in the state of Acre, Fuccio et al. (2003) estimated the most commonly hunted species by analyzing notices of violation recorded by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) between 1989 and 1997. These species were peccary, deer, tapir, and monkeys. Except for the monkey species, the present study also showed the presence of these species among those reported from Acre state.

In a similar study, Dias-Junior (2010) identified the most threatened species in the region of Macapá city by analyzing notices of violation recorded by state environmental institutions between 2005 and 2009. The most frequently seized species were paca, agouti, armadillo, capybara, deer, tapir, and peccary, all of them also identified in the present study in the northern region.

Studies based on ethnozoology performed in the Amazon region show similar results. Bonaudo et al. (2005) identified paca, armadillos and peccary as being the most hunted species for subsistence along the transamazon highway. Mesquita and Barreto (2015) conducted a study in four localities of Amazon region and found that ungulates and rodents were the most frequently hunted mammals groups. The most reported species were peccaries and deer. Van Vliet et al. (2014), studying the trifrontier region between Brazil, Colombia and Peru found that the most hunted species were paca, tericaya turtle and currassows and being paca, tapir, peccary and red brocket deer the most commercialized species. A survey conducted by Baia-Junior et al. (2010) in the Brazilian Amazon characterizing the bushmeat trade in local markets concluded that the most hunted species were capybara, cayman, paca, armadillos, deer, mata-mata (Chelus fimbriatus) and opossum. Except for the opossum, the present study also identified these mammals species in the northern region, however, the most seized were armadillos, paca, peccary and tapir (38.5%, 24.2%, 15.4% and 9.9% of total identified mammals, respectively).

In the northeastern region, a study conducted by Barbosa et al. (2011) characterized the most hunted species for subsistence in the semiarid region found that birds and mammals were the most hunted groups. Dantas-Aguiar et al. (2011), in a study conducted in a community from Bahia State found that the hunting activities in that region were for subsistence or recreation purposes. The most hunted species were armadillos, peccary, deer, birds, agouti, opossum and pigeons.

Nevertheless birds seizures were not reported in the period analyzed in the present study, the importance of mammals bushmeat in the northeastern region of Brazil was also noted from the data provided by environmental police: the region reported 39.1% of all mammals hunted evaluated. The most seized mammals species in northeastern region were Brazilian guinea pig, fox and capybara (performing 77.7%, 4.75% and 3.65% of total identified mammals seizures, respectively).

Generally, in southeastern Brazil, slaughter rates are high for peccaries and capybaras (Nogueira-Filho and Nogueira, 2000). In a qualitative study conducted at the Atlantic coast of southeastern region by Hanazaki et al. (2009), mammals species such as paca, deer, armadillos, agouti, opossum, capybaras, tamadua and peccaries where cited as being hunted by local communities. Except for the agouti, the present study also found these species being illegally hunted in the southeastern region. Among the identified species, the most common were paca, armadillos, capybara, and deer (30%, 23.1%, 20% and 13.1% of seizures, respectively).

With a national scope, our survey showed high slaughter rates for the Brazilian guinea pig, armadillos, paca, and capybara (18.5%, 5.9%, 5.3% and 3.7% of total seizures); seizures of Brazilian guinea pig were reported only in the northeast region. The importance of this species in the northeast was also found in ethnozoology studies, where it appears as being one of the most hunted species (Barbosa et al., 2011). Only armadillos and deer seizures were reported in all the evaluated regions. Except for the southern region, that poorly identified its seizures, paca and capybaras can be considered as being hunted all over the country.

In conservation terms, armadillos, the second most frequently cited animals in reports, comprise a group that includes the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus) and Brazilian three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus), listed as vulnerable by the IUCN (2014).

In 2014, the Brazilian Environmental Ministry published a list of threatened species, being 12,256 species evaluated. The list classifies species such as the giant armadillo as endangered, and the white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), Brazilian three-banded armadillo, tapir, and giant anteater as vulnerable (Brazil, 2014). It was found that, together, armadillos, peccaries, tapirs and anteaters compose 9.7% of total seizures.

Our survey showed that the most frequently seized fish species were arapaima (also known as pirarucu), tambaqui, pacu, matrincha, and flagtail Prochilodus. Although the arapaima has been classified as vulnerable by the IUCN, it is currently listed as “data deficient”, mainly due to the lack of studies about this species. Illegal activities have deleterious impacts on the population growth rate of arapaima, due to the delay of sexual maturation and removal of potential spawners (Castello et al., 2011). Government policies, such as the establishment of a minimum capture size and of closed seasons, have been implemented to protect the arapaima, but the high seizure rates reported in the present survey, 62.7% (mainly in Amazonas State), indicate that much improvement is needed regarding supervision and enforcement. Fish genera listed as vulnerable or endangered by the Brazilian Government include genus Prochilodus, Leporinus, Brycon, and Pimelodus (Brazil, 2014). Our study indicates that 83.84% of the fish seized for those four genus occurred in the state of Minas Gerais.

Studies of IUU fishing are also lacking. Many seized species were not identified, and frauds may affect the accuracy of data. Seized material in filet form is particularly difficult to identify through morphological analysis. Another basic problem for the control of fishing activities is the ambiguity of classification. For example, the popular name “pacu” (1.7% of total identified fish seizures) is applied to many species belonging to different genera and families. Genetic tools can be used to authenticate seized material that cannot be identified morphologically (Ardura et al., 2010) but genetic markers are not available or not routinely applied in Brazil.

The illegal fishing activities show great regional differences. In five different regions evaluated, from 30 species reported, 21 species were reported in only one geographical region, 8 were reported in 2 regions and 1 was reported in 3 regions. None species was reported in all the five geographical regions evaluated.

The statistical analyses showed that both data for illegal hunting and fishing were non-parametrics. A Spearman Correlation Test was performed and the results showed that number of illegal fishing seizures were not correlated with the State area (r2=0.400 and p=0.210). The statistical analyses with illegal hunting seizures showed a negative correlation between number of seizures and State area (r2=−0.606 and p=0.0427). From these results, it's possible to conclude that the amount of seizures depends on enforcement efforts.

The data provided by environmental military police for the present survey showed that the organization of information markedly differed among states, with a complete lack of standardization. The main differences lie on the use (or non-use) of species identification (even applying common names) and the reporting of data. For example, Santa Catarina State, had great seizures numbers for bushmeat, but classifies these seizures only at Phylum level. On the other hand, Amazonas State classifies almost all the seized material by species common name.

Although such data provided by environmental military police have received little academic attention, they have great informative potential. This police force is present in almost all Brazilian municipalities and it has territorial coverage exceeding that of all other institutions. Moreover, Brazilians customarily call the military police to report the occurrence of crimes, even those committed against the environment. To enable better use of this source of information, we recommend the standardization of procedures for data collection and the generation of standard activity reports for all States. As a complement to other strategies for hunting and fishing activities data collection, such information is important in the development of conservation policies and improvement of our understanding of the deleterious impacts of illegal hunting and fishing on Brazilian ecosystems.

ConclusionsThis survey provides a characterization of illegal hunting and fishing activities in Brazil from January 2013 until June 2014.

Regarding bushmeat seizures, a markedly importance of mammals species was noted: 63.7% of all seizures related to illegal hunting were mammals species. The lack of species identification was also noted: 54.3% of total seizures were not identified.

For fish species, 27.2% were not identified, and the Amazon species arapaima and tambaqui were the most seized fish.

It is important the expansion of our knowledge about the impacts of illegal activities in all Brazilian biomes and the collection of data that can be used for developing and implementing conservation policies and law enforcement actions. Notices of violation and reports made by the military police are great sources of information, comparable to reports produced by environmental organizations and ethnozoology studies, but the presentation of such information must be better organized.

Finally, it is critical the need to develop methodologies that can be used directly or indirectly by the responsible institutions in the identification of animals seized.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank the environmental military police command centers that participated in this study and kindly provided their reports. This study received financial support from CAPES (Edital Ciências Forenses n° 25/2014).