Sport fishing is an activity responsible for moving millions of dollars around the world. However, this activity is also considered to cause habitat degradation and promoting several negative effects on the ichthyofauna. The ``Iguaçu Dourado'' project, presented here, seeks to intensify the potential of sport fishing in the Iguaçu River Basin. Although not explicit, the project intends to introduce Dourado (Salminus brasiliensis), as well as to encourage sport fishing of the species in the Iguaçu River Basin. Twenty specimens were captured in the Salto Santiago and Salto Osório reservoirs from 2003 to 2016, thus indicating that the invasion of S. brasiliensis can be successful and extremely harmful to the endemic fauna of the basin. We believe that the so-called project is characterized by an attitude of eco-vandalism, promoting the illegal release of species outside its area of occurrence. Awareness-raising measures as well as educational programs should be addressed so that the population can be informed about the issue of invasion of non-native species.

Recreational sport fishing is practiced worldwide (Peixer and Petrere Jr., 2009), with resultant important economic and social values in many countries (Pimentel et al., 2001; Britton and Orsi, 2012; Ellender and Weyl, 2014). This fishing modality is responsible for a considerable exchange of income and services related to fishing activities (Sipponen and Gréboval, 2001; Peixer and Petrere Jr., 2009). Despite the positive aspects of sport fishing, related primarily to the economy and to tourism, sport fishing is also considered to be the cause of severe habitat degradation and the decline of fish stocks around the world (e.g. Britton and Orsi, 2012; Ellender and Weyl, 2014), especially by promoting the negative effects of commercial fishing (Cooke and Cowx, 2006).

Presently, sport fishing is one of the main vectors of non-native fish introductions worldwide (Pimentel et al., 2001; Vitule, 2009; Britton and Orsi, 2012; Daga et al., 2016). In Brazil, on the grounds that few native fish species are suitable for sport fishing, the introduction of non-native species, such as the peacock-bass (Cichla spp.) and the dourado Salminus brasiliensis (Cuvier, 1816), has been encouraged and even carried out by government agencies, as well as illegally by fishermen, with the aim of developing this fishing modality in the country (Vitule, 2009; Vitule et al., 2014).

The introduction of such species as the dourado and peacock-bass, considered non-native top-predators, can cause significant deleterious effects on native fish populations (Pelicice & Agostinho, 2009; Vitule et al., 2014). Introductions of non-native piscivorous fish can be especially harmful because of their extremely aggressive predatory behavior (Pelicice & Agostinho, 2009; Gubiani et al., 2010; Vitule et al., 2014), and their greater potential for competition when compared with native predators (Pereira et al., 2015).

The introduction of dourado and prospects for the Iguaçu River basinIguaçu River basin is considered to be an unique fish ecoregion (Abell et al., 2008), rich in endemic genera and species (Baumgartner et al., 2012), including many undescribed species (Pavanelli and Bifi, 2009), which is already severely threatened by numerous impoundments and by the introduction of non-native fishes (Gubiani et al., 2010; Daga and Gubiani, 2012; Vitule et al., 2014; Daga et al., 2015, 2016). Currently 29 non-native fish species have been recorded in this region, seven of which are considered top-predators exercising strong predation pressure on native communities (Daga et al., 2016).

The dourado, Salminus brasiliensis, is native to southern South America in the Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay rivers, the Laguna dos Patos drainage, and the Chaparé and Mamoré rivers (Amazon Basin) (Reis et al., 2003; Graça and Pavanelli, 2007). Adults of dourado are aggressive visual predators and primarily piscivorous. The species has recently expanded its range in South America with the help of deliberate introductions (Vitule et al., 2014).

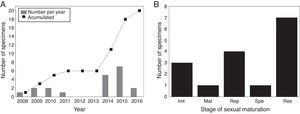

The record of the introduction and subsequent spread of S. brasiliensis in some of the main Brazilian river basins, as well as its recent record in the Guaraguaçu River basin, is related directly to human activity and, in particular, to sport fishing (Vitule et al., 2014). In the Iguaçu River, the dourado was first recorded in 2008 (Gubiani et al., 2010); records of its occurrence in the river have increased over time (Fig. 1A).

Number of individuals of Salminus brasiliensis (Cuvier, 1816) recorded per year (bars) and cumulative (line), from 2008 (first record) to 2016, in the Salto Santiago and Salto Osório reservoirs, Iguaçu River basin (A) and sexual maturation stages of the specimens collected in the Iguaçu River basin (imt, immature; mat, maturation; rep, reproduction; spe, spent; res, rest) (B).

Sampling conducted from 2003 to 2016 in Salto Santiago and Salto Osório reservoirs (for more details see Gubiani et al., 2010; Gerpel/Instituto Neotropical de Pesquisas ambientais/Tractebel, 2015) recorded 20 specimens of dourado (Fig. 1A), with an average standard length of 40.40±14.50cm (SD) (ranging from 17 to 70cm) and average weight of 2106.10±2359.00g (ranging from 88.60g to 9964.00g).

The diet of S. brasiliensis is predominantly composed of fish, especially species of genus Astyanax (Esteves and Pinto Lôbo, 2001). This genus is very abundant and known to be an important food resource for many top-predator fish species in the Iguaçu River (Garavello and Sampaio, 2010; Daga and Gubiani, 2012; Baumgartner et al., 2012; Delariva et al., 2013). In addition, it has a high rate of endemism among its species (Pavanelli and Bifi, 2009). Therefore, because of the high availability of resources, the invasion of S. brasiliensis will probably be successful in this region, where it has the potential to be extremely harmful to the endemic fish fauna (Gubiani et al., 2010; Vitule et al., 2014).

The size at first maturity in S. brasiliensis, an important measure for inferring the reproductive potential of a fish population (Vazzoler, 1996), was found to range from 37.80cm for females and 32.40cm for males (Suzuki et al., 2004). During the period from 2003 to 2016, only two immature males smaller than the recorded size at first maturity were captured, indicating that this species is probably already reproducing in the region (Fig. 1B). However, the migratory behavior of dourado could limit their invasion success since the area is known to be highly impounded (Daga and Gubiani, 2012; Antonio et al., 2007; Daga et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the invasion success of S. brasiliensis in other Neotropical rivers with similar limitations on migration has already been reported (Ruschi, 1965; Vitule et al., 2014), which leads us to conclude that its successful establishment in the Iguaçu River is only a matter of time.

Project ‘Iguaçu Dourado’ and the risks associated with the introduction of the dourado in the Iguaçu River basinThe project ‘Iguaçu Dourado’ (Fig. 2A) aims at the implementation of a program for the sustainable exploitation of sport fishing tourism in the Iguaçu River basin. In its publicity material the project claims to be in favor of the conservation of the region and the sustainable development of the local population (Fig. 2B). Although not explicit, the intention of the group is to introduce and/or maintain the dourado by catch and release programs, as well as by clandestine restocking by individual or group activity, is clear (e.g. Fig. 2C and D), even though the organizers are aware that this practice is prohibited by the federal laws nos. No. 5197/67 and No. 9605/98. Therefore, this project can be characterized as embodying an attitude of eco-vandalism, and can be understood as the deliberate and illegal release of species outside of their natural areas of occurrence (Cambray, 2003; Abilhoa et al., 2011). In addition, one of the most negative points of Project ‘Iguaçu Dourado’ is that it is masked as a correct environmental initiative (see attached links on capture and restocking of non-native species in the Iguaçu River basin). According to Azevedo-Santos et al. (2015), environmental education and information are the best ways to avoid the introduction of fish species, but in Project ‘Iguaçu Dourado’ they are used to abet a completely wrong initiative. The project's offer of “educational” workshops, especially those for children from six to 12 years old, is, in reality, an attempt to induce children and young people to think that what they are doing is correct, which completely undermines the environmental education of future citizens.

Publicity material of project for the sustainable exploitation of sport fishing tourism in the Iguaçu River basin, entitled ‘Iguaçu Dourado’: cover material (A), project introduction (B), description of the proposal for the development of sport fishing in the basin (C) and justification for the project (D). Text translation into English is in Supplementary Material.

Therefore, we wish to emphasize strongly that this method of promoting sustainable sport fishing tourism in the Iguaçu River is inappropriate, especially since it implicitly suggests the use of a non-native species. In order to achieve the real purposes of this project, the development of sustainable sport fishing in the region, the incentive for sport fishing must be directed toward native fish species, and combined with an educational awareness program and with sustainable recreational sport fishing practices, under the supervision of the appropriate public agencies (e.g. Azevedo-Santos et al., 2015).

Legal measures to prevent the introduction of non-native species in Brazil have failed so far, precisely due to the lack of governmental supervision and the lack of public information about the existence of specific legislation (Vitule, 2009; Azevedo-Santos et al., 2015). What is needed is a change in the behavior of the population through education and information, the most effective way to mitigate the deliberate introductions of non-native species (Azevedo-Santos et al., 2015). Additionally, the media in general, and more specifically TV shows and magazines about sport fishing, should act as channels of information concerning which species are not native to a region, and be aimed at informing and educating fishermen, so that they can become active partners in combating the invasion of non-native species (Vitule, 2009).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Links to anecdotal images and videos from YOUTUBE:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6lHEAQwHvA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqNUTSevaeU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_1fBRLQmIs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hpl9eYTS36I

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IP2W9VRSzi4

http://www.portaldecanoinhas.com.br/noticias/11924

http://www.pescamadora.com.br/2015/11/grupo-realiza-soltura-equivocada-de-alevinos-no-rio-iguacu-pr/