Hummingbirds are one of the most threatened bird groups in the world. However, the extent to which global climate change (GCC) and habitat loss compromise their conservation status remains unclear. Herein, we proposed to: (1) assess how predicted GCC impacts the distribution of non-migrant hummingbirds according to their conservation status, degree of restriction and habitat specificity; and (2) delineate priority conservation areas where species could persist in the face of both threats. We estimated the potential distributions of 49 species under current and future climates (year 2040, 2060, and 2080), analyzing the effects of current habitat loss and the importance of existing Protected Areas (PAs) on the species’ ranges and hummingbird hotspot areas in Mexico. Our projections were consistent in the identity of the species that are most vulnerable to GCC: while 10.2% of species will have potentially habitat gains/stability (“winners”), the remaining 89.8% of species (“losers”) will face habitat reductions under new climate conditions. These changes were mostly related to temperature increases (>2 °C) and rainfall decreases (<50 mm). The combined impacts of GCC and habitat loss may represent a higher risk, leading to an average reduction of ~26-59% in species’ ranges. Already-established Mexican PAs cover ~12% of the hummingbirds’ current ranges, but showed an important reduction of surface across the species distribution (on average >15%) and hotspot areas (>60%) for future. We identified highly resilient priority areas across southern Mexico, in Oaxaca and Guerrero. Ambitious conservation actions by decision-makers are now crucial to avoid losing these highly-vulnerable taxa.

Hummingbirds (Aves: Trochilidae) are a New World bird family comprising ca. 330 species. This specialized nectarivorous taxon plays an important role in ecosystem functioning because they act as pollinators for nearly 15% of the plant species in North and South America (Schuchmann, 1999; Buzato et al., 2000). In addition, these small (2.5–24 g) birds have always been important in human culture (e.g., representing gods, soul carriers, love and fertility, good luck, and wellness) even in modern societies (Mazariegos, 2010). Therefore, they are often used by scientists and conservationists as ecological indicators and promoters of conservation policies. Unfortunately, these taxa are considered one of the most threatened groups in the world (https://www.iucnredlist.org/). Hence, there is a growing interest in understanding the effects of both anthropogenic disturbances (habitat loss and fragmentation) and global climate change (GCC) on the spatio-temporal distribution patterns of hummingbirds (e.g., Buermann et al. 2011; Infante et al., 2020), and in trying to identify priority sites for their conservation purposes.

All 58 of the hummingbird species distributed in North America are found in Mexico, a mega-diverse country; 49 species are resident and nine are Neotropical migrants (Arbeláez-Cortés and Navarro-Sigüenza, 2013; Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014). For most of these species, current distribution patterns are relatively well known. In terms of species composition, six faunistic groups have been suggested across Mexico: the main mountain ranges, the Pacific tropical dry forests, the tropical dry forest of the Gulf of Mexico slopes, the humid tropical forest in southern Mexico, and the Yucatan and Baja California peninsulas (Arizmendi et al., 2016). In terms of conservation, at least six species are considered range-restricted and endangered at the global level (Berlanga et al., 2008; Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014; IUCN, 2015). Also, most species of hummingbirds (all species except Lophornis brachylophus, Eupherusa cyanophrys, and E. poliocerca) have been reported in ~85% of the National Protected Areas (PAs) network in Mexico (Arizmendi et al., 2016). However, despite this increase in the ecological and biogeographical information, details of hummingbirds’ response to accelerated landscape transformation and global warming are poorly known and remain unclear (but see Lara et al., 2012; Mayani-Parás et al., 2020; Prieto-Torres et al. 2021b). This lack of information restricts our understanding of their vulnerability and extinction risk, and thus, potential impacts on natural ecosystems (see Pearson et al., 2019). Given that a reduction in pollination could create a feedback loop with biodiversity loss and degradation of ecosystem services (Ollerton et al., 2011), there is an urgent need to review future hummingbird conservation threats.

This latter is critical because Mexico continues to have high annual deforestation rates (over 1% nationwide; FAO, 2001), with more than 13.5 million ha of ecosystems lost over the last 50 years (see Mendoza-Ponce et al., 2020; Mayani-Parás et al., 2020). Moreover, recent studies have indicated a spatially heterogeneous increase in mean annual temperature over the last one hundred years (see Cuervo-Robayo et al., 2020). Indeed, the effects of GCC will likely outpace habitat destruction as a leading cause of loss in species richness and driver of species extinctions in the coming decades (e.g., Peterson et al., 2002, 2015; Zamora-Gutierrez et al., 2018; Esperon-Rodriguez et al., 2019; but also see Mayani-Parás et al., 2020). Hummingbirds (both threatened and non-threatened species) are not exempt from these critical scenarios (Lara et al., 2012; Prieto-Torres et al., 2020, 2021b). PAs network may be less effective for conserving species under GCC, mainly because they may not cover species’ modified future distributions (Jones et al., 2018; Esperon-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Maxwell et al., 2020). Therefore, future conservation efforts should take into account the combined effects of habitat loss and GCC in order to detect which species are most vulnerable versus resilient, and which regions are most stable versus susceptible to biodiversity loss (see Pecl et al., 2017; Pearson et al., 2019; Mendoza-Ponce et al., 2020).

Niche-based models (also called “ecological niche models” and “species distribution models”) are powerful tools that provide a conceptual and methodological approach for addressing the aforementioned challenges (see Peterson et al., 2011). These models rely on correlative relationships between field observations (species’ occurrences) and environmental factors, allowing us to predict the areas that are currently suitable (i.e., Grinnellian niches; Rödder and Engler, 2011) for species and how environmental changes could impact their distribution (i.e., whether they will persist, increase, disappear or shift). This information can be used to test ecological hypotheses about species’ dispersal ability and physiological performance under climate variations (e.g., Buermann et al. 2011; Esparza-Orozco et al., 2020; Cornejo-Páramo et al., 2020). The use of niche-based models by ecologists and conservation managers has exploded over the last two decades, with hundreds of papers published annually on conservation planning under GCC (see Araújo et al., 2019).

In this paper, we proposed to: (a) assess how predicted GCC could impact the distribution of 49 resident hummingbird species; (b) estimate the vulnerability of species in the face of GCC taking into account their conservation status, degree of restriction and habitat specificity; and (c) determine the effects of current habitat loss and the importance of the existing PAs network to safeguard both species ranges and hummingbird hotspots throughout Mexico. Based on this information, we provide new and more accurate evidence to guide the decision-making processes for the establishment of long-term and highly resilient priority conservation areas across Mexico. The priority areas identified here could help optimize the protection of these highly vulnerable taxa in the face of future environmental changes.

MethodsSpecies occurrence and climatic input dataWe included the 49 resident hummingbird species inhabiting Mexico (Arbeláez-Cortés and Navarro-Sigüenza, 2013; Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014). All species names followed Chesser et al. (2020). We downloaded occurrence data from: (a) online databases (Global Biodiversity Information Facility [GBIF; https://www.gbif.org/], SiB-Colombia [https://sibcolombia.net/], and EncicloVida [https://enciclovida.mx/]); and (b) the “Atlas de las Aves de México” (Navarro-Sigüenza et al., 2003). Access numbers for downloaded GBIF records are detailed in Appendix S1. In view of the shortcomings of GBIF data (Yesson et al., 2007) and the need for good quality data to avoid effecting model performance (Beck et al., 2014; Pérez-Navarro et al., 2021), we checked and vetted records carefully to remove erroneous and duplicate records. For each species, to avoid biases derived from spatial autocorrelation in areas that are heavily represented in the data, we applied a buffer distance (based on the mean distance among its occurrence records; Appendix S1) and retained only information corresponding to localities that were separated by at least this buffer distance. For those records from 2001 to 2020, we also performed an outlier exclusion procedure in the environmental space by removing points that fell outside the interquartile range of three environmental variables (annual mean temperature [bio 01], annual precipitation [bio 12], and precipitation seasonality [bio 15]) for occurrences from 1970 to 2000 (e.g., Robertson et al., 2016, Prieto-Torres et al., 2020). Then, we removed spatially duplicate points near to each other by ca. 5 km2 (i.e., the cell size resolution used for predictor variables). After these steps, we retained 30,468 unique occurrence records for all of the species.

Predictor variables were selected from bioclimatic variables (~5 km2 cell size resolution) from the WorldClim project 2.1 (Fick and Hijmans, 2017). We excluded the four variables (bio 8, bio 9, bio 18, and bio 19) that combine temperature and precipitation, owing to known artefacts (Escobar et al., 2014). To reduce dimensionality and collinearity of environmental layers, we applied two approaches: (1) selection of a subset of variables based on a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r < 0.8) and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF < 10), using the “usdm” R package (Naimi, 2015); and (2) derivation of a set of four variables (explaining up to 95% of the total variance) using a Principal Component Analysis (see Hanspach et al., 2011), as implemented in the “ENMGadgets” R library (Barve and Barve, 2016). We selected the best approach for models building based on the statistics estimated in the “kuenm” R package (Cobos et al., 2019).

For models based on future climate projections (year 2040, 2060, and 2080), we used climate data from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6; Stoerk et al., 2018) available at the Worldclim web portal. Because predicted future species distributions can vary widely, we selected five global climate models based on results obtained from GCM compareR's web application (Fajardo et al., 2020). We adopted the “storyline” approach, where different GCM projections are classified into self-consistent narratives that represent specific future climate conditions (Zappa and Shepherd, 2017): (i) high temperature and low precipitation compared to the ensemble projection (CanESM5), (ii) low temperature and high precipitations compared to the ensemble projection (MIROC6) and, (iii) temperature and precipitations close to the average ensemble projection (BCC-CSM2-MR, CNRM-CM6-1, and IPSL-CM6A-LR). Additionally, it is important to note that these five models show improvements in the estimation of precipitation values, zonal-mean atmospheric fields, equatorial ocean subsurface fields, and the simulation of El Niño-Southern Oscillation in the Americas (Cook et al., 2020; Zelinka et al., 2020). All projections were performed using an intermediate Shared Socio-economic Pathways scenario (i.e., SSP 370), which assumes high greenhouse gas emission and low climate change mitigation policies (Riahi et al., 2017).

Ecological niche and species distribution modelsWe modelled the potential distribution for each species using MaxEnt version 3.4.3 (Phillips et al., 2017). We decided to use this software given its good performance using presence-only data (Elith et al., 2011), and because it allows a calibration protocol to assess model complexity by selecting the best modelling parameters (see Muscarella et al., 2014; Cobos et al., 2019). Although the choice of background data is an important step into modelling method using presence-only data (Phillips et al., 2009), we did not include a sampling bias variable because there is no existing sampling bias layer that covers our study region and group, and we do not have the necessary sampling effort data to generate such a layer. Moreover, following Barve et al. (2011), we created an area for model calibration (known as “M”; Soberon and Peterson, 2005) that reflects the accessible historical areas and restriction regions for each species. We established “M” based on the intersection of occurrence records with the Terrestrial Ecoregions (Dinerstein et al., 2017) and the Biogeographical Provinces of the Neotropics (Morrone, 2014). The hypothesized areas of accessibility for each species are provided in Appendix S2.

All models were run allowing “unconstrained extrapolation” and “extrapolation by clamping” in Maxent projections, which allowed us to identify potential novel conditions that could be considered suitable for each species in the future scenarios (Elith et al., 2011, Merow et al., 2014). Models for species with 9-14 records were developed using all presence data (using MaxEnt default parameters) and evaluated with a Jackknife test (Pearson et al., 2007). For species with ≥15 records, models were generated using the “kuenm” R package (Cobos et al., 2019; available at: https://github.com/marlonecobos/kuenm) to perform a calibration protocol assessing model complexity (Merow et al., 2014). To do this, we created 570 candidate models by combining two distinct sets of environmental predictors, 19 regularization multiplier values (RM: 0.5 – 8.0) and 15 feature classes (i.e., combinations of linear, quadratic, product, and threshold). We used 30% random subsets of occurrence data for model evaluation (i.e., model testing and selection of best models). The best models were chosen based on the omission errors (Anderson et al., 2003), the partial ROC test (Peterson et al., 2008) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Merow et al., 2014; Muscarella et al., 2014). After model calibration, we created models with the selected parameter values, 500 iterations with 10 bootstrap replicates, and cloglog output (Phillips et al., 2017).

Then, to generate the distribution maps for each species under each climate scenario, we first calculated median values across replicates to summarize model predictions (Campbell et al., 2015). Then, we created presence-absence maps from the logistic values of suitability maps, using as the threshold value the “tenth percentile training presence” in order to reduce commission (i.e., the false-positive rate) errors (Liu et al., 2013). For each species, the future geographic distribution (year 2040, 2060, and 2080) were obtained manually by overlaying the binary projections from the five global climate models, allotting “presence” to a pixel where the majority of predictive models coincided (i.e., suitable in 3 or more models = 1). For all species, models were calibrated using the available data for their entire current range, and then cropped to the approximate geographic extent of Mexico (Fig. 1).

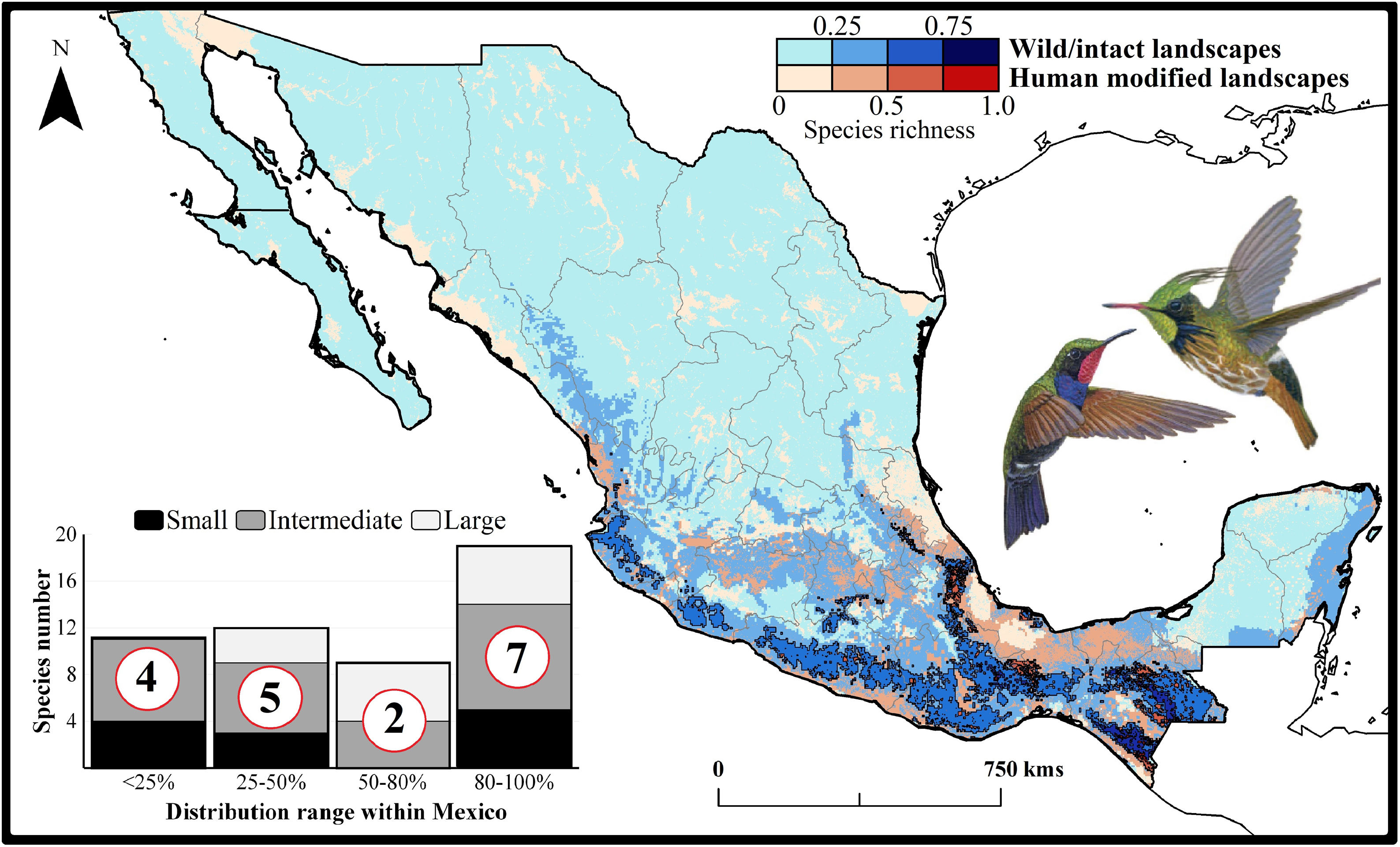

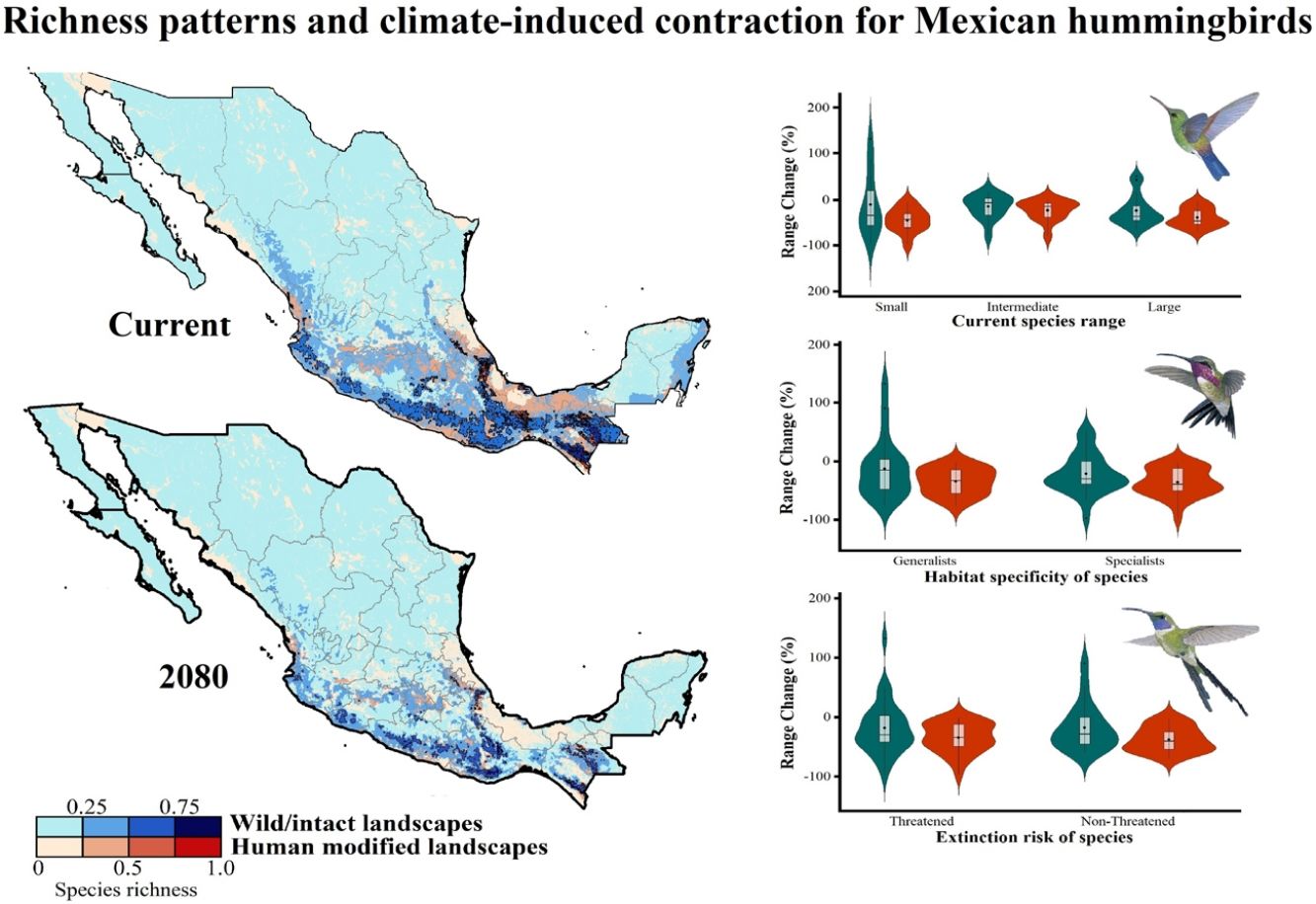

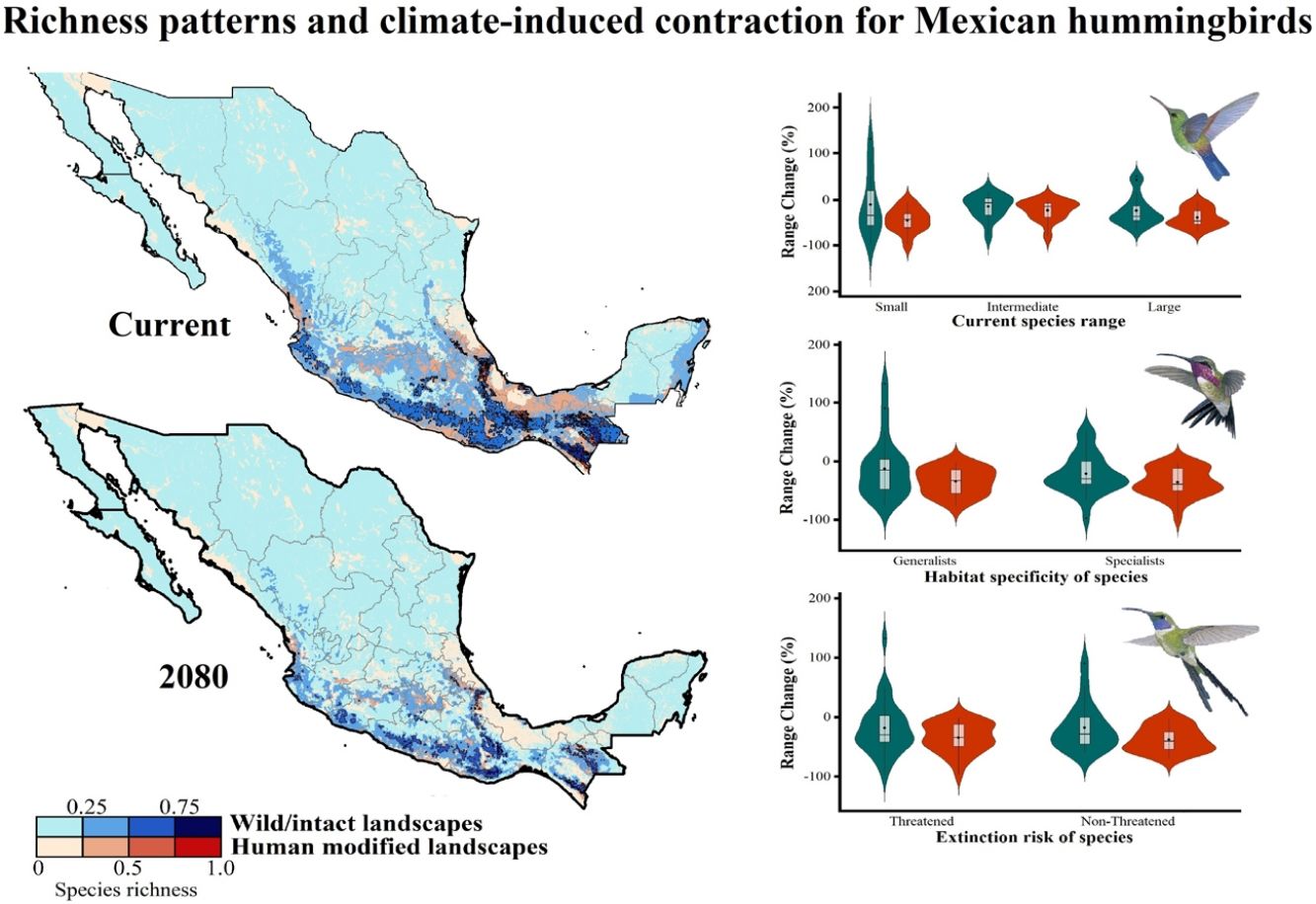

Current patterns of species richness maps for non-migrant hummingbird species (n = 49 spp.) across Mexico. The color gradient represents species richness: darker color indicates sites with higher species richness (i.e., hotspots) in both human-modified (red) and intact (blue) landscapes. The inset bar plot indicates the proportion of current distribution area within Mexico for hummingbirds, showing the number of species categorized as small, intermediate, and large distributional ranges. Circles in bars correspond to the number of threatened species (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) in each range size category. The birds shown in the figure are Lamprolaima rhami (left), and Lophornis helenae (right). The bird pictures were taken from "Colibríes de México y Norteamérica" (Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014)

Finally, using the “ntbox” R package (Osorio-Olvera et al., 2020), we performed the Mobility-Oriented Parity (MOP; Owens et al., 2013) test to identify areas where strict or combinational extrapolation risks could be expected in model transfers, given the presence of non-analogous conditions (see Owens et al., 2013; Alkishe et al., 2017). Areas in which extrapolation risks were detected were deleted from our binary results (suitable areas) for the subsequent analyses. This step is important for proposing conservation areas, as protecting areas are more advantageous where a species has low uncertainty values for predictions (i.e., one would rather fail to create PAs where a species occurs than to create PAs where it does not occur; see Velazco et al., 2020).

Data analyses: impacts of climate changes and habitat lossWe measured the potential impacts of GCC on the geographic range of each species under two different dispersion scenarios (Peterson et al., 2002). The “contiguous dispersion” scenario assumes that species would be able to disperse through continuous habitat, but not jump over barriers (i.e., all the cells with suitable conditions within "M" in the future are considered part of its future distribution range). In the “non-dispersion” scenario, it is assumed that species are unable to disperse at all (i.e., only those cells that are occupied in the present can be occupied in the future). This non-dispersion scenario only allows for negative responses (decreases in distributional range) to GCC; therefore, it must be considered the most “unfavorable” for the species (Peterson et al., 2002; Atauchi et al., 2020; Prieto-Torres et al., 2020).

For each species, losses and gains due to GCC were calculated from the binary maps by subtracting the future from current models (following Thuiller et al., 2005). Also, where a loss of suitable areas was predicted in future-projected models, we calculated the differences between current and future values for the environmental variables (Atauchi et al., 2020). In addition, for each dispersal assumption scenario, a Kruskall-Wallis test was performed to estimate the species’ vulnerability (based on species’ range changes) in the face of GCC as a function of their extinction risk in Mexico (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 [available at: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle_popup.php?codigo=5173091), their degree of geographical restriction and their habitat specificity. We classified geographical restriction into three categories based on the number of occupied sites (pixels) in the current species range: large (in the upper quartile, 249,677 km2), intermediate, and small (in the lower quartile 25,067 km2). Habitat specificity was described as species generalists or specialists (Appendix S1) based on their habitat use (e.g., Stotz et al., 1996; Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014; Schulenberg, 2019).

To assess the effects of current habitat loss (i.e., human modified areas that may be unsuitable for some species) in our models, we used the 2017 land cover and vegetation map generated by the Mexican Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). This vectorial map (scale of 1:250 000) was generated from photointerpretation of Landsat TM5 satellite images from 2014 and 2015, validated in the field, and it included the information on location, distribution, and extent of different plant communities (including intact and modified areas) and agricultural uses (see metadata [available on: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/usosuelo/] for more information about the map). We reclassified this map using the “majority” resampling technique in ArcMap 10.2.2 (ESRI, 2010) to discriminate pixels representing extremely disturbed landscapes (i.e., areas occupied by crops, deforested areas, farming areas, pastures, and urban settlements) in order to identify highly human-modified areas. We then calculated the average extent of species distribution (current vs. future) that had extremely disturbed landscapes in this current map. Because future habitat loss estimations are not available for the entire study area, this approach is useful for improving our knowledge of future threats to forest-dependent species that are unable to persist in an agricultural matrix (Bregman et al., 2014); thus it is commonly used in the literature.

We also identified hummingbird hotspots (i.e., sites whose species richness exceeded half of the maximum values observed) and determined their overlap with current highly human-modified areas. For this, we first obtained the species richness pattern by summing all binary species maps for each year, then coverted them into a standardized raster (ranging 0 to 1) by dividing each raster by its maximum value. These maps were classified using a color key based on four equal intervals, and then overlapped with the human-modified areas map (following Bolochio et al., 2020). All of these post-modelling analyses and statistical calculations were performed in ArcMap using the “raster calculator” toolbox.

Protected Areas network and long-term hummingbird conservationWe estimated the importance of the existing PAs network for hummingbird protection by calculating the proportion of potential distributional areas within the current PA system. To do this, we overlapped the raster of current Mexican PAs with each species’ distribution and the binary raster of hummingbird hotspots for each climate scenario (see above). Also, to test the efficiency of PAs, we compared the distribution of hummingbird species concentration values (based on the standardized raster ranging 0 to 1) for pixels with at least one species at present and ran a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to verify whether the curves within and outside PAs differ significantly between them (e.g., Ramírez-Albores et al., 2021). PA boundaries were obtained from a shapefile downloaded from the Mexican Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP; available on: http://sig.conanp.gob.mx/website/pagsig/info_shape.htm), selecting both terrestrial official PAs and voluntary conservation areas.

Also, following the criteria proposed by Rodrigues et al. (2004) and Goettsch et al. (2019), we identified covered (i.e., if a predetermined percentage of its distribution was included), partial gap and gap (i.e., if it was not included) species within current PAs. The percentage used is referred to as the conservation target for each species: for species with geographic ranges of ≤1,000 km2 is required that entire range have been covered, whereas for species with ranges ≥250,000 km2 only 10% of their distribution must be included in PAs. For species with intermediate geographic ranges, we determined conservation targets by interpolating between these two extremes (Rodrigues et al., 2004; Goettsch et al., 2019).

To determine key regions for Mexican hummingbirds’ long-term conservation, we summed binary hotspot maps (current and future) to detect the consensus areas among them. Then, we calculated the area (in km2) and percentage of consensus areas that overlap with: (i) already-established Mexican PAs, and (ii) current human-modified areas. From this perspective, the consensus hotspots that did not match among maps correspond to “priority conservation sites” that will be protected in the near future because they represent the areas where a high species concentration could persist in face of both habitat loss and GCC impacts. To assess the degree of resilience of these priority areas to future land-use changes, we compared our results with a human-modified areas map for the 2050's (choosing the “Middle of the road” intermediate scenario from the application of CLUMondo application). This global map (available on: https://www.environmentalgeography.nl/site/data-models/data/implementing-ssps-in-clumondo/) shows the future modified areas based on the projected demand for crop production, bovines, goats and sheep and urban area, as these were the exogenous productivity increase factors due to technological change per year (for a detailed explanation see Van Asselen and Verburg, 2013).

Finally, to assess the representation levels of species richness in these highly resilient priority areas, we performed a complementarity analysis as suggested by Margules and Sarkar (2009). To do this, we built a presence–absence matrix data based on each cell, analyzing them in Excel 2013 using an iterative process to choose the highest richness cells with more complementary species until completing all possible species (e.g., Humphries et al., 1991; Sánchez-Ramos et al., 2018). The complementarity was plotted in a species accumulation curve using the “BiodiversityR” R package (Kindt, 2016).

ResultsSpecies models and current hummingbird species richness pattern in MexicoAll of our maxent models exhibited highly significant values for the partial ROC test (range = 1.16 – 1.94, P < 0.05) for species with ≥15 occurrence records, while the Jackknife test showed statistically significant (P < 0.01) values when the threshold was applied for species with nine occurrence records. On average, models had low omission errors, with values of 4.6 ± 5.1%. Based on these performance estimates, we considered our models to be accurate (i.e., have good discrimination capacity) in recovering the ecological niches for each species. Parameter settings and performance values for each model are detailed in Appendix S1.

The current predicted distribution area for hummingbirds in Mexico ranged from 225 km2 (Cynanthus forficatus) to 797,150 km2 (Cynanthus latirostris). On average, 60.1% of species’ whole distribution occurred within Mexico. About 38.8% (n = 19) of the hummingbird species possess ranges that overlap at least 80% of Mexico’s surface; while 42.9% (n = 21) of species show overlap values of <50% of their distribution within Mexico. According to our range size categories, 49% of the species had intermediate sized ranges in Mexico, 26.5% of the taxa had large ranges, and 24.5% had small ranges (Fig. 1). Based on the Mexican list of extinction risk (Appendix S1), eight species are classified as threatened, one as endangered, nine as under special protection, and 31 are not included in any risk category.

There was a variable number of total hummingbird species per site, ranging from 1 to 27 spp. (mean of 5.8 ± 4.7). The current hotspots (>0.5, dark colors in Fig. 1) covered an area of 108,562 km2, and are mainly located across southern Mexico, in the states of Oaxaca (33.7%), Chiapas (27.4%), Guerrero (18.4%), and Veracruz (6.9%).

Impacts of current habitat lossOur models showed an important degree of overlap between highly human-modified areas and estimated species ranges (mean of 24.5 ± 10.8%). The species with the highest proportions of suitability climate-areas within current human modified areas were Saucerottia cyanura (51.8%), Pampa excellens (49.8%), and Phaethornis striigularis (40.8%). We observed that the majority of species (57.1%) had between 20-40% of their distribution within highly human-modified areas, while 30.6% (15 spp.) showed overlap values of 10-20%. Only three species had less than 10% of their potential range in human-modified areas: Eupherusa cyanophrys (6.83%), Lophornis brachylophus (5.84%), and Basilinna xantusii (3.55%). Furthermore, 15.5% of current hummingbird hotspots areas in Mexico overlapped with these highly human-modified areas (see Fig. 1).

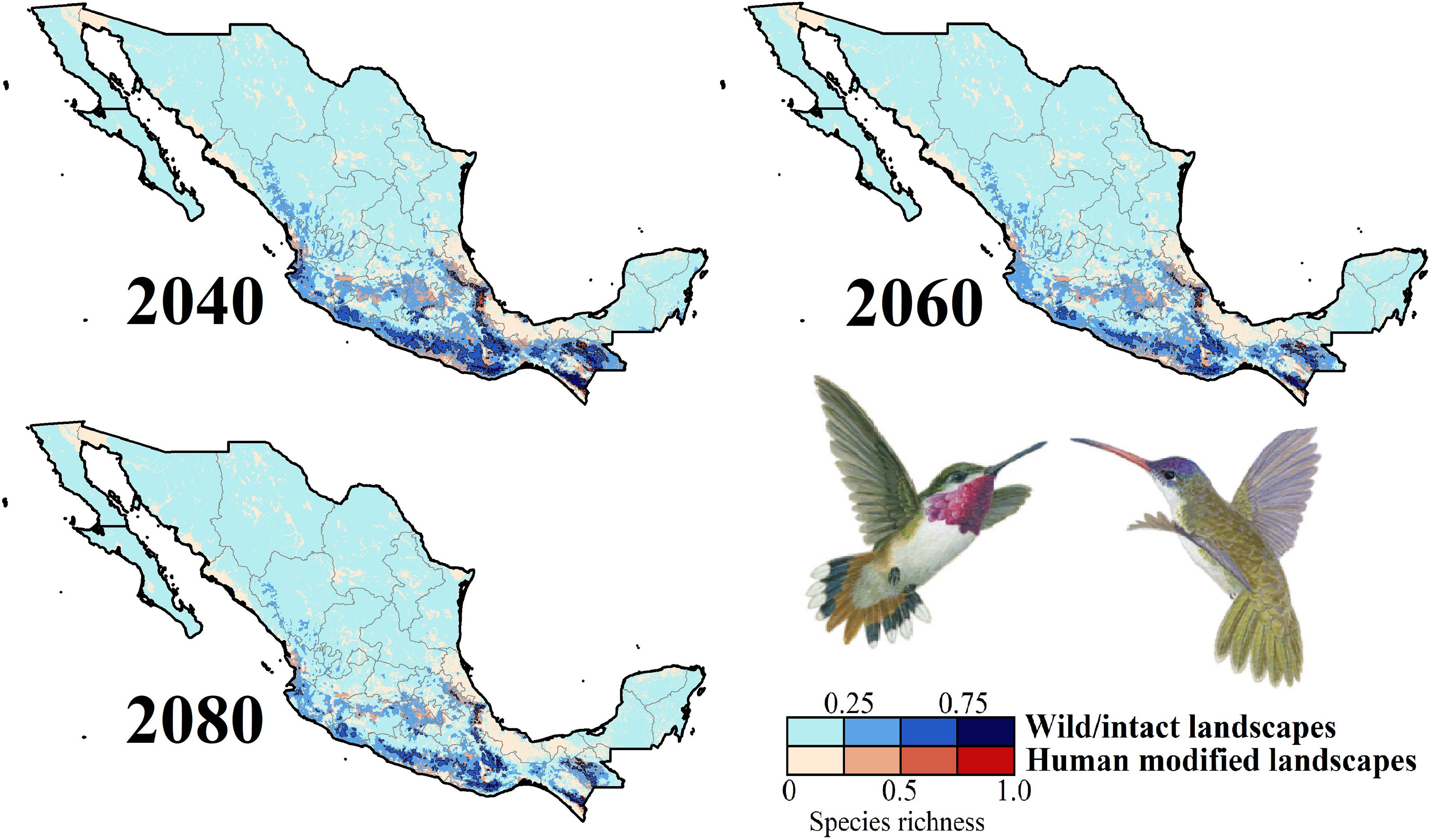

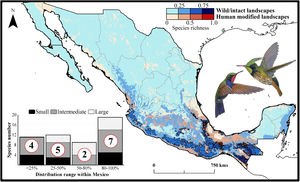

Impacts of future climate changeOverall, the following patterns emerged from our projections (Fig. 2; Appendix S3): (i) climate change will lead to range reductions for hummingbirds in Mexico by an average of 4.6% [2040’s] – 32.3% [2080’s] if we assume contiguous dispersion scenarios and 23.6% [2040’s] – 48.4% [2080´s] if we assume the non-dispersion scenario; (ii) these distributional areas in the future showed a decrease in values of suitability for projections by an average of 0.05 [2040’s] – 0.11 [2080’s]; (iii) for those regions where suitable areas will likely decrease, temperature metrics ––especially annual mean temperature, maximum temperature of the warmest month, and mean temperature of the coldest quarter–– tended to increase by more than 2.0 °C; while (iv) the values for annual precipitation and wettest quarter tended to decrease on average 85.1 mm and 52.1 mm, respectively; (v) species richness of hummingbirds will decrease, on average, by 37.3% [dispersion scenario] – 40.6% [non-dispersion scenario] across ~50% of Mexico; and (vi) the hotspots areas will also decrease in size (ranging from 34.3% [2040’s dispersion scenario] to 53.8% [2080´s non-dispersion scenario]), occupying higher elevation zones (at least ~260 m; independently of dispersion scenarios) than their current average distribution (1,227 ± 653 m asl). Moreover, extinction (i.e., disappearance of suitable areas) is the most likely future for the insular C. forficatus. The MOP analysis indicated that, regardless of our dispersion assumption, areas where strict extrapolation occurs represent a low proportion (on average <5%) of predictions by models in the future climates across Mexico (Appendix S4). This pattern suggests that there is scarce or null proportion of novel conditions that could be considered suitable for each species in the future. In this sense, the general reduction in species ranges corresponded to changes in climate-suitability available currently.

Species richness patterns for non-migrant hummingbird species (n = 49 spp.) across Mexico projected for years 2040, 2060, and 2080 assuming contiguous dispersion. The color gradient represents species richness for each scenario analyzed. Darker color in maps indicates the higher hummingbird hotspots areas (i.e., higher species richness) in both human-modified (red) and intact (blue) landscapes. Detailed results for the no dispersal ability scenarios are available in the Appendix 2. The birds shown in the figure are Selasphorus heloisa (left), and Leucolia violiceps (right). The bird pictures were taken from "Colibríes de México y Norteamérica" (Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014)

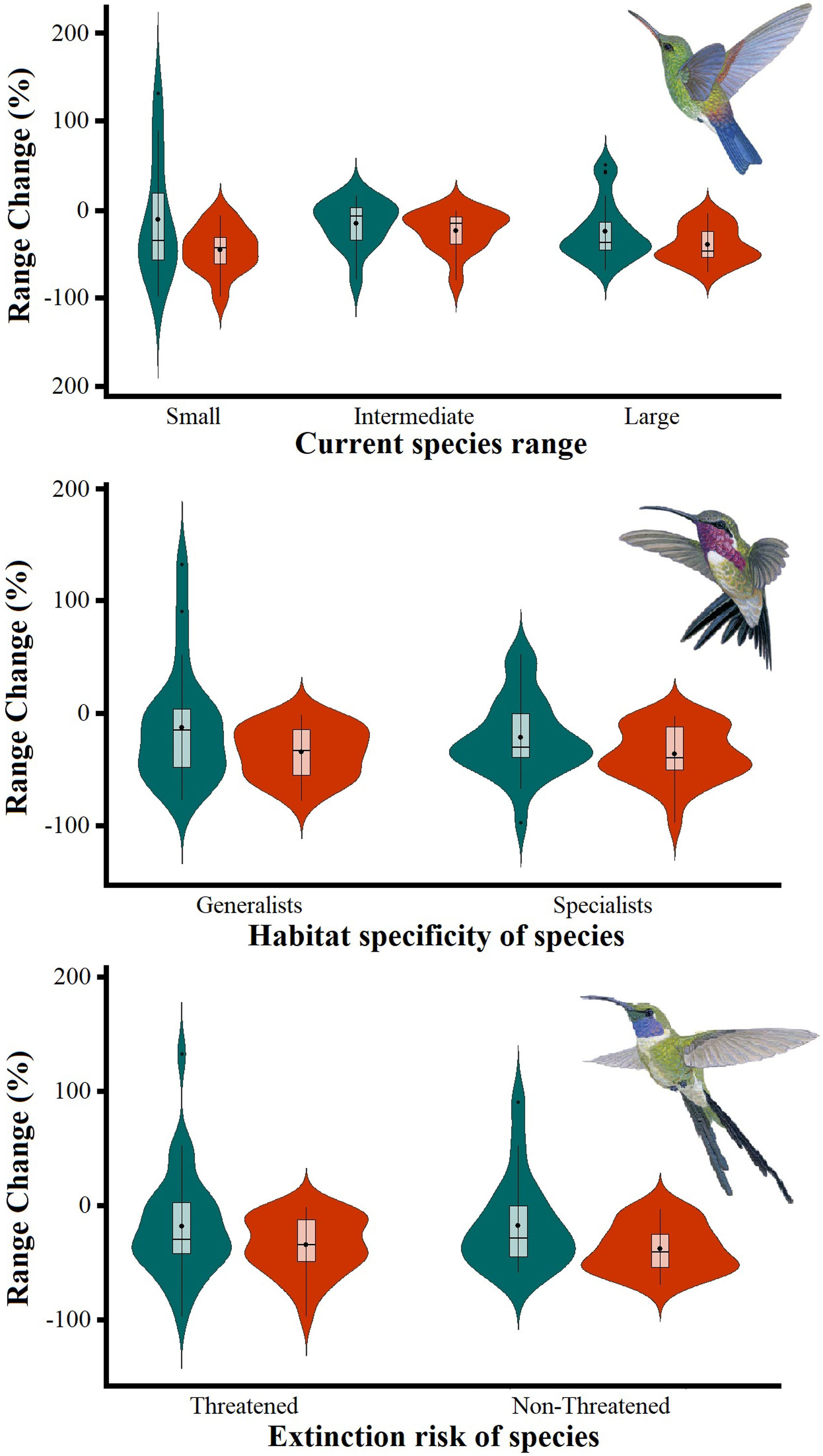

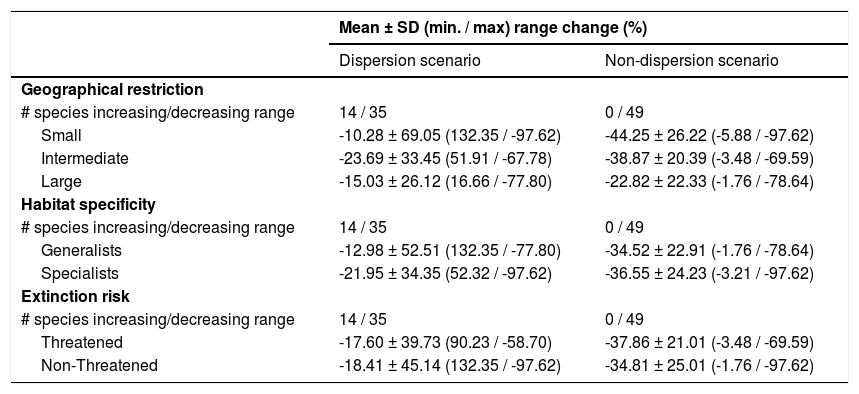

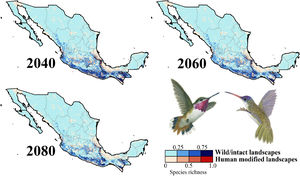

The Kruskal–Wallis tests showed that species’ sensitivity to climate change was not significantly different across years under dispersion and non-dispersion scenarios, among the categories of extinction risk (χ2 = 4.4; df = 3; P = 0.23) or habitat specificity (χ2 = 4.4; df = 3; P = 0.22). There was, however, a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 11.9, df = 5; P = 0.03) in climate-induced range contraction among the three geographical restriction categories (Fig. 3). Both of the dispersion scenarios yielded the same patterns; although the no dispersal scenario led to larger decreases in species’ predicted range (Fig. 3; Table 1). Under the full GCC scenarios, we observed that 89.8% of the species showed large habitat reductions (“losers”), while the remaining 10.2% (five species) were predicted to have large potential habitat gains/stability (“winners”) under future climate conditions. These five species ––Cynanthus canivetii, C. latirostris, Eupherusa ridgwayi, Leucolia viridifrons, and Amazilia rutila–– showed range stabilities of >95%, even under the non-dispersion scenario.

Differences in the proportion of range change (%) due to climate-induced contraction for the non-migrant hummingbird species (n = 49 spp.) in Mexico, under the two considered dispersion assumptions (contiguous dispersion in green, no dispersion in red), considering the species extinction risk, degree of geographical restriction, and habitat specificity. The Kruskal–Wallis tests only showed statistically significant differences (χ2 = 11.9, df = 5; P = 0.03) for species vulnerability among the range size categories. Birds shown in the figure are Saucerottia cyanura (small range; upper panel), Calothorax pulcher (specialist; in the middle panel), and Doricha enicura (Threatened; lower panel). The bird pictures were taken from "Colibríes de México y Norteamérica" (Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014)

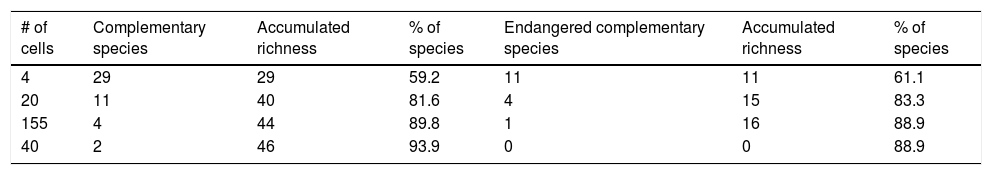

Predictions of range change (in percentage) for non-migrant hummingbird species (n = 49 spp.) across Mexico considering the national extinction risk, degree of geographical restriction, and habitat specificity of species.

| Mean ± SD (min. / max) range change (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dispersion scenario | Non-dispersion scenario | |

| Geographical restriction | ||

| # species increasing/decreasing range | 14 / 35 | 0 / 49 |

| Small | -10.28 ± 69.05 (132.35 / -97.62) | -44.25 ± 26.22 (-5.88 / -97.62) |

| Intermediate | -23.69 ± 33.45 (51.91 / -67.78) | -38.87 ± 20.39 (-3.48 / -69.59) |

| Large | -15.03 ± 26.12 (16.66 / -77.80) | -22.82 ± 22.33 (-1.76 / -78.64) |

| Habitat specificity | ||

| # species increasing/decreasing range | 14 / 35 | 0 / 49 |

| Generalists | -12.98 ± 52.51 (132.35 / -77.80) | -34.52 ± 22.91 (-1.76 / -78.64) |

| Specialists | -21.95 ± 34.35 (52.32 / -97.62) | -36.55 ± 24.23 (-3.21 / -97.62) |

| Extinction risk | ||

| # species increasing/decreasing range | 14 / 35 | 0 / 49 |

| Threatened | -17.60 ± 39.73 (90.23 / -58.70) | -37.86 ± 21.01 (-3.48 / -69.59) |

| Non-Threatened | -18.41 ± 45.14 (132.35 / -97.62) | -34.81 ± 25.01 (-1.76 / -97.62) |

We observed that the combined effects of GCC and current human-modified areas would reduce species distribution by an average of 26.1% [2040’s] – 45.9% [2080’s] assuming a dispersion scenario, and 39.9% [2040’s]–59.1% [2080’s] if they cannot disperse. Overall, in both dispersion scenarios, 22.1% of potential distribution for species in the future overlapped with the currently highly human-modified areas (i.e., likely unsuitable for some species). This fact is particularly important for five species (Hylocharis eliciae, P. excellens, Phaethornis longirostris, P. striigularis, and S. cyanura), for which more than 43% of their remnant distribution in the future fell within these human-modified areas. Furthermore, on average ~12.2% of remnant hummingbird hotspots in the future overlapped within current highly human-modified areas.

Protected Areas network and long-term hummingbirds’ conservationAlready-established Mexican PAs cover, on average, 11.6 ± 7.8% of the distribution area of all of the hummingbird species, and 13.3 ± 11.1% of the distribution of threatened species. Currently, the best represented species within the PAs were: Phaeochroa cuvierii (47.3%), Heliothryx barroti (25.9%), and Pampa rufa (25.5%). However, a large number of hummingbird species (n = 25) had less than 10% of their range protected. In fact, according to the species’ conservation targets, six species (12.25%) were considered fully covered, while 41 (83.67%) species were partial gap species, and two (L. brachylophus and C. forficatus) were identified as gap species. Overall, we observed no significant differences for species richness values (P > 0.05) between areas within the existing PAs network (6.4 ± 4.7 spp.) and outside the PAs (6.0 ± 4.7 spp.). Moreover, we observed that only 8.9% of current hummingbird hotspots were included within some PAs category.

Our models predicted a critical reduction (on average 14.9% [dispersion scenario] – 31.8% [non-dispersion scenario]) in suitable areas for hummingbirds within the limits of several PAs in the future. We also noted a significant reduction in mean species richness (P < 0.05) within PAs under the climate change scenarios for the 2040’s (6.3 ± 4.4 [dispersion scenario] and 5.6 ± 4.1 [non-dispersion scenario] spp.), 2060’s (5.7 ± 4.1 and 5.1 ± 3.7 spp.), and 2080’s (4.9 ± 3.5 and 4.5 ± 3.2 spp.). Likewise, we observed that existing Mexican PAs had on average and regardless of the dispersal scenarios, only 6.8% overlap with the potential hotspot areas identified in the future. This represents an important reduction (>60%) of protected surface across the hotspot areas in the future.

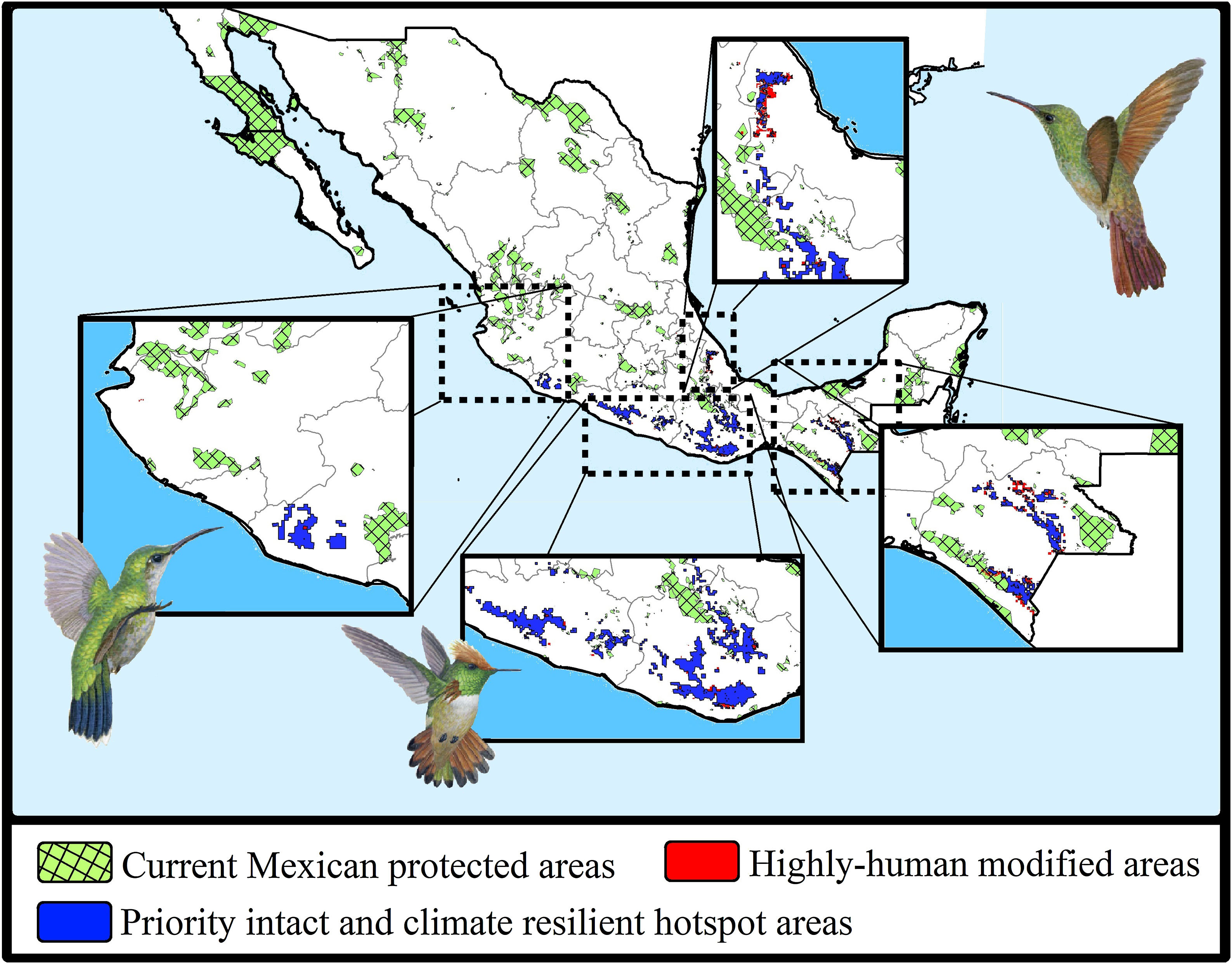

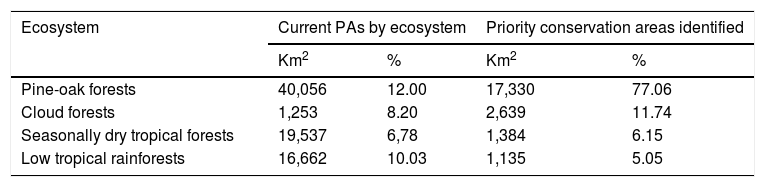

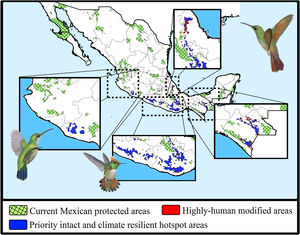

The consensus hummingbird hotspot areas under both dispersion scenarios for future climates showed high (62%; i.e., 26,689 km2) overlap values. Approximately 10.8% of the area of these long-term climate-resilient sites overlapped within current highly human-modified areas, while only ~6% were including within existing PAs. Our analyses showed a high proportion (84.3%; 22,488 km2) of long-term hummingbird hotspots areas with good-quality forests outside the PAs limits (Fig. 4). These priority conservation and highly-climate resilient areas in the future cover mostly wide areas in Oaxaca (44.8%), Guerrero (23.8%), Chiapas (17.8%), and Michoacán (7.9%). The complementarity analysis showed that 219 cells of these resilient areas in the future contain 93.9% of hummingbird species richness (46 species, including ~89% of endangered species; see Table 2). The species accumulation curve reached its asymptote in a few cells (see Appendix S5). The three hummingbird species that were not included in these areas were Basilinna xantusii, C. forficatus, and Doricha eliza.

Maps showing the current Mexican protected areas (PAs), the priority and climate-resilient hummingbird hotspot areas identified in our study. For the proposed areas, we show the sites that coincided with highly human-modified areas (red) for both current and 2050 scenarios. Birds shown in the figure are Thalurania ridgwayi (♀endemic to western Mexico; left), Lophornis brachylophus (endemic to Guerrero state; middle), and Saucerottia beryllina (right). The bird pictures were taken from "Colibríes de México y Norteamérica" (Arizmendi and Berlanga-García, 2014)

Number of complementary species per grid cell of the total species richness and richness of endangered species.

| # of cells | Complementary species | Accumulated richness | % of species | Endangered complementary species | Accumulated richness | % of species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 29 | 29 | 59.2 | 11 | 11 | 61.1 |

| 20 | 11 | 40 | 81.6 | 4 | 15 | 83.3 |

| 155 | 4 | 44 | 89.8 | 1 | 16 | 88.9 |

| 40 | 2 | 46 | 93.9 | 0 | 0 | 88.9 |

Moreover, according to the Mexican terrestrial ecosystem classification (INEGI-CONABIO-INE, 2008), we observed that these long-term consensus priority areas were distributed in four ecosystems (Table 3): pine-oak forests (17,330 km2; 77.06%), cloud forests (2,639 km2; 11.74%), seasonally dry tropical forests (1,384 km2; 6.15%), and low tropical rainforests (1,135 km2; 5.05%). Finally, it is important to note that our priority consensus conservation areas have 14.6% (3,288 km2) overlap with areas expected to be highly human-modified by the 2050's (Fig. 4).

Priority conservation and highly resilient areas identified for non-migrant hummingbird species throughout Mexico by terrestrial ecosystem. The total area (in km2 and percentages) of existing PAs was obtained from maps produced by the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP; available at: http://sig.conanp.gob.mx/website/pagsig/info_shape.htm).

| Ecosystem | Current PAs by ecosystem | Priority conservation areas identified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km2 | % | Km2 | % | |

| Pine-oak forests | 40,056 | 12.00 | 17,330 | 77.06 |

| Cloud forests | 1,253 | 8.20 | 2,639 | 11.74 |

| Seasonally dry tropical forests | 19,537 | 6,78 | 1,384 | 6.15 |

| Low tropical rainforests | 16,662 | 10.03 | 1,135 | 5.05 |

Undoubtedly, the both climate warming and land-use change will have a serious impact on individual species and communities of hummingbirds throughout Mexico in the coming decades, even under the more optimistic change scenarios (e.g., Lara et al., 2012; Correa-Lima et al., 2019; Chávez-González et al., 2020; Prieto-Torres et al., 2021b). More importantly, our results reinforce the widely accepted idea (see Jones et al., 2018; Maxwell et al., 2020) that current PAs are not now effective for safeguarding these species, nor will they be into the future (see also Esperon-Rodriguez et al., 2019). This bleak scenario will lead to most species being highly vulnerable to extinction due to the reduction of range size and the increase in fragmentation (Zamora-Gutierrez et al., 2018; Lovejoy and Hannah, 2019; Mayani-Parás et al., 2020). It is imperative that policy-makers promote policies that are resilient to both threats as soon as possible. From this perspective, our results represent a valuable guide using scientific evidence on which species and areas require attention to establish new efforts for efficient long-term conservation planning in Mexico for these highly vulnerable and ecologically specialized Neotropical bird taxa.

This latter is noteworthy considering that more than three quarters of species showed a reduction of suitable habitat areas as a consequence of GCC. These results are in agreement with other studies in Mexico, not just for birds (Lara et al., 2012; Prieto-Torres et al., 2020, 2021a, 2021b) but for a wide variety of organisms, including mammals, amphibians, reptiles and plants (e.g., Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2012; Sinervo et al., 2017; Mason-Romo et al., 2018; Ureta et al., 2018; Arenas-Navarro et al., 2020). These patterns of change are attributed to the expected increase in the average global temperature and decrease in the annual precipitation across the region (Cuervo-Robayo et al., 2020; Esperon-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Hidalgo, 2021), which could promote changes in the physiological responses and activity patterns of the biota. Therefore, as our results show, under future climates it is likely that species will be pushed toward higher elevations (even losing geographical ranges), where future humidity will be a key limiting factor for the biota (Buermann et al., 2011; Harsch and HilleRisLambers, 2016). In fact, we observed that the overall patterns of geographic change were consistent among all of the climate and dispersal scenarios we considered, reducing uncertainties in our forecasting models (see Peterson et al., 2018; Araújo et al., 2019). Nevertheless, our results should be taken with caution because species’ potential to adapt to future conditions is very difficult to predict, since their adaptive potential is influenced by many additional factors that we did not evaluate here, such as reproductive rates, physiological capacity, and habitat requirements (Peterson et al., 2002; Ortega et al., 2019).

When changes in local climates exceed the range of natural climate variation, species may acclimate by adjusting physiologically (through phenotypic plasticity) within individual’s lifetimes (Urban et al., 2014) and/or shift their distribution to avoid dying (Peterson et al., 2002; Lovejoy and Hannah, 2019). In the particular case of hummingbirds, their responses may be determined by performance of hovering flight and feeding across these challenging new environments (Buermann et al., 2011). Higher elevation locations have reduced air density and oxygen availability, and high-elevation hummingbirds exhibit flight adaptations (e.g., lower wing loadings, increase in the wing stroke amplitude and changes in flight kinematics, etc.) that compensate for these effects (Altshuler et al., 2004; Buermann et al., 2011). So, if low-elevation species are not able to quickly adapt to new environments at higher elevations, population sizes would be expected to decrease, and their future survival may be threatened. Therefore, the impacts and extinction risks may be even more drastic than the results obtained here. More studies analyzing the ability of these taxa to rapidly adapt or move into new areas and environmental conditions are needed (see de Matos Sousa et al., 2021). For this, the implementation of monitoring programs is essential, especially for the species and zones that are predicted to suffer the most drastic decreases.

Clearly, the existing scenario of loser and (few) winner species for new climate conditions support the idea that a species’ ecological generalization (including niche breadth and range size) is one of the key attributes affecting their extinction risk. In fact, our models show that most of the winner species do not have a particularly habitat affinity (e.g., A. tzacatl, A. prevostii, and S. cyanura), whereas species that have an arid/dry affinity (e.g., B. xantusii) are expected to be more negatively affected in the extent of their suitable areas. This is expected because small-range species are typically specialists with narrow ecological niches (e.g., Sonne et al., 2016), so they are less likely to be able to colonize novel conditions in the near future (e.g., Thuiller et al., 2005; Broennimann et al., 2006). This pattern could explain, in fact, the extinction scenario obtained for the insular C. forficatus in the future. Moreover, this is consistent with previous studies in Mexican seasonally dry forests which suggest higher vulnerability to GCC and habitat loss for these biota (Prieto-Torres et al., 2016, 2020, 2021b). Nevertheless, it is important to note that recent studies have shown hummingbird range expansion associated with urbanization, even under non-suitable climatic conditions (e.g., Greig et al., 2017; Battey, 2019). Therefore, we recommend further fieldworks testing the projections (i.e., hypothesis) from our results to obtain reliable knowledge about the species’ dynamic responses to future environmental scenarios. Based on our results, the species H. eliciae, P. excellens, P. longirostris, P. striigularis and S. cyanura represent promising models for future studies addressing these questions.

Although hummingbird-pollinator losses due to deforestation and agricultural intensification have not yet been documented in Mexico, circumstantial evidence suggests this is already happening (e.g., Infante et al., 2020). Certainly, there are hummingbirds species that occur within transformed areas, but whether they successfully establish reproductive (e.g., subcanopy is an essential element for successful nesting) and permanent resident populations in these transformed habitats is unknown for most species (Smith et al., 2014). In this sense, further fieldwork is needed because niche modeling-based approaches have some limitations that could preclude the identification of continuously changing trajectories and responses. First, there are uncertainties when forecasting species distributions depending on the algorithm used (see Qiao et al., 2015). Second, land uses should be used as environmental variables for distribution modelling, but temporal quality data reporting land uses change (on past, present and future) are hard to get. In addition, there are factors that influence species occurrence at fines scales that we could not include in our approach, such as species interactions, population processes, phenological acclimation, topographic and micro-climates (Araújo and Luoto, 2007; Araújo and Rozenfeld, 2014; Hannah et al., 2014).

Indeed, an important drawback of our study is that we only considered abiotic effects, but previous studies suggest that the spatio-temporal distribution patterns of hummingbirds could vary also due also to the flowering phenology of the plants they pollinate (Correa-Lima et al., 2019; Chávez-González et al., 2020; Infante et al., 2020). Thus, it is likely that other factors such as interspecific competition (see Rodríguez-Flores et al., 2019) and changes in floristic composition represent further challenges for these species in the future. From this perspective, areas predicted to be climatically suitable but where essential hummingbird resources are lost (e.g., nesting sites, nectar sugar content from plants) may be in fact an unsuitable habitat for this specialized nectarivorous group. This issue remains poorly studied, but our intuitive hypothesis do not seem totally wrong (see Atauchi et al., 2018). More research is needed on these ideas (Hegland et al., 2009).

It is important to note that shifts in the regional structure of hummingbird-pollinated plant networks (see Chávez-González et al., 2020) may have significant consequences for ecosystem functioning, which could lead to negative cascade effects on animal-plant interactions (Pauw, 2019). In fact, it is also expected that the unprecedented redistribution of biodiversity at the level of taxonomic diversity will lead to an overall reduction in alpha phylogenetic and functional diversities within communities (Graham et al., 2017; Prieto-Torres et al., 2021b), affecting the responses, traits and resilience of ecosystems to disturbances (Weiss and Ray, 2019). In this sense, novel and disappearing hummingbird assemblages are likely to pose management challenges for future conservation (Graham et al., 2017). This is not a minor detail and, therefore, research to understand the susceptibility of pollinator-plant interactions to environmental changes (including different dimensions of diversity) must be considered a top-priority question (see Pearson et al., 2019). From a strategic point of view, this information provides critical context to make better decisions about biodiversity protection and avoid wasting valuable conservation resources (Jones et al., 2018). For developing countries such as Mexico where economic resources for conservation are limited, this is crucial for policy makers (Maxwell et al., 2020).

Conservation implicationsDespite the increase in the extent of terrestrial PAs over the past 20 years, we detected some important gaps for hummingbirds conservation across Mexico (see Arizmendi et al., 2016). For instance, it is likely that the proportion of species’ ranges contained within PAs will decrease substantially in the future, and it is also important to note that most the priority areas that are highly resilient to GCC and land use change are located outside the current PAs (Fig. 4). Aditionally, currently there are at least two globally threatened and endemic species without protection. This leaves the overall long-term conservation picture for hummingbirds quite weak in Mexico. Future efforts to maximize the performance of the PA network must be planned differently.

From this perspective, the priority conservation areas found here provide insights into where to focus future conservation expansion efforts to accomplish a representative and connected PA network in the long-term. This is important because to truly conserve biodiversity, we must ensure that PAs are not only designated in sufficient quantity, but also in locations that are suitable for imperiled species through time (Hannah et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2010; Prieto-Torres et al. 2016, 2020). Thus, research like this study, focused on identifying these “safe places” (i.e., sites with high species richness where human induced changes in the near future are not expected) are of paramount importance. Given that these areas may remain well-preserved in the future, the necessary resources and efforts should be directed for their long-term maintenance and preservation. The areas we point out for prioritization here coincide strongly with sites previously identified as important in Mexico: 91.9% correspondence with priority areas for conservation and research of terrestrial vertebrates (mammals, birds and amphibians; Nori et al., 2020), 30% correspondence with extreme-priority attention sites for biodiversity conservation (CONABIO, 2016), and 45.1% correspondence with biological corridors across southeastern Mexico (Coordinación de Análisis Territorial, 2015). This suggests that in addition to their importance for hummingbirds, they are also important sites for entire biotas across the region, especially considering the role of hummingbirds as pollinators (see Buzato et al., 2000). In this sense, it is also advantageous that a large proportion of these “safe places” does not match the places targeted for agriculture expansion in future scenarios (Fig. 4); thus, executable actions could be possible if there is also political will.

Our study also highlights the need to review the threat status for several species and to expand conservation practices to ecosystems that are underrepresented within the PAs. This could help national and local governments, as well as NGOs, civil society, and business to assess and prioritize strategies and monitoring studies for species and sites for forest or landscape restoration. Of particular concern are both seasonally dry forests and cloud forests, which despite having high levels of species richness are the least protected, have the highest deforestation rates over the last decade, and are at high risk from GCC (Ponce-Reyes et al., 2012; Prieto-Torres et al., 2016, 2021a; Mayani-Parás et al., 2020). However, it is not just more land that is needed to guarantee the medium- and long-term conservation of hummingbirds; management actions should also focus on maintaining suitable habitats in unprotected areas, on mitigation of GCC impacts (Esperon-Rodriguez et al., 2019), and on assessing the effectiveness of conservation efforts under different anthropogenic practices (e.g., Naime et al., 2020; Sánchez-Romero et al., 2021). This is very important considering that endemic and threatened species ––such as B. xantusii, C. forficatus, and D.eliza–– are in fact distributed outside from the highly resilient priority areas identified herein.

Additional efforts involving complementary programs for vegetation restoration are also crucial to avoid not only the loss of biodiversity, but also the loss of ecosystem services. In fact, optimal biodiversity maintenance requires habitat conservation in concert with restoration activities at the landscape scale—the latter will likely be increasingly important in a world of changing climate (see von Holle et al., 2020). Therefore, it will be important to promote and financially support forest protection and/or restoration. In this sense, the “payment for ecosystem services” to landowners that preserve forest remnants represents a positive and effective strategy to reach this important goal (Naime et al., 2020; Sánchez-Romero et al., 2021). From this perspective, we argue that most Mexican municipalities have to be challenged to promote the protection of their biodiversity with significant actions to decrease the species extinction risk. Therefore, we hope that these new findings and proposals will trigger the interest of biologists, conservationists and policy-makers and motivate them to delve more deeply into long-term conservation of biodiversity in Mexico.

Author contributionsDAP-T and MCA conceived and designed the study. DAP-T, LENR and MCA compiled the database of available records. DAP-T and DRF performed the ecological niche models, spatio-temporal analyses, and MOP tests. All authors contributed to the statistical analysis and interpretation of results, as well as the writing of the manuscript.

FundingThis work was supported by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA; grant to MCA number PAPIIT-IN221920), and the Programa de Investigacion en Cambio Climático (PINCC; grant to MCA), both at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). The Rufford Foundation (DAP-T’s projects: 16017-1 and 20284-2) and Idea Wild also provided funding. The Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) and the Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas at UNAM provided Masters [number 1084487] scholarship grants to DRF. The DGAPA-UNAM provided a postdoctoral fellowship at the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, UNAM, to LENR.

Competing interests statementThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statementThe authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials. Interested readers to other material could to request them from the both first [DAP-T: davidprietorres@gmail.com] and corresponding author [MCA: coro@unam.mx].

Thanks to the curators and researchers at Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera” (Facultad de Ciencias; UNAM), including Adolfo G. Navarro-Sigüenza and Luis A. Sánchez-González, who provided access to the species’ occurrence records used here and contributed suggestions as birds experts. We also thank Javier Fajardo for providing technical assistance using the GCM compareR's web application based on data from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6). We also appreciate the financial and logistical support provided by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA, UNAM) and the Programa de Investigación en Cambio Climatico (PINCC; UNAM) that allow us to perform this study. The first author (DAP-T) also extends his gratitude to the Rufford Foundation and Idea Wild for the financial sources received for the compilation of species occurrence data into Mexican dry forests used in this study. DRF was supported by the Master scholarship grant [number 1084487] from CONACyT (Mexico). LEN-R are grateful for postdoctoral scholarship awarded by DGAPA for work carried at Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, UNAM. We also thank Lynna M. Kiere for feedback on English language editing and manuscript proofreading, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.