The subdivision of Amazonia in large interfluvial areas of endemism (delimited by major rivers), based mostly on bird species distributions, has been a recurrent starting point to the understanding and conservation of the biome’s megadiversity. Yet, no areas of endemism or regionalization have been described for the well over 100 bird species that occupy floodplain habitats along the rivers, and thus are not expected to have ranges delimited by the rivers themselves. Here, through spatial analyses of updated range maps (based on a dataset with more than 80 thousand occurrence records), for a revised list of 182 floodplain specialized bird taxa, we identified ten areas of endemism and a complementary habitat-specific regionalization of the biome (with 13 regions). For the floodplain birds, Amazonian major rivers are segmented into distinct areas of endemism rather than these areas being delimited by the rivers. The well-established large interfluvial areas of endemism are appropriate for terra firme species but fail to account for taxa associated with floodplain habitats. Natural history traits and taxonomy of endemic species suggest that both ecological and historical processes have contributed to the patterns found. This new regionalization is consistent with the view of Amazonia as a mosaic of ecoregions and offers a complementary scheme for studies on the evolution and conservation of the floodplain component of its biodiversity.

Areas of endemism, where at least two species are endemics, represent “treasure maps” for biodiversity discovery and conservation, in the sense that they may indicate where new species may be discovered, how evolutionary processes may be understood, and how distinctive communities are distributed and so can be protected. This is especially true for Amazonia, the world’s largest tropical forest and most diverse biome (Antonelli et al., 2018). Despite apparent uniformity, the Amazonian Forest has been subdivided in areas of endemism that are correspondent with the region’s largest interfluves (Cracraft, 1985; Silva et al., 2005). This singular biogeographic regionalization is based mainly on the distributions of bird and primate species, which often have ranges delimited by major rivers (Wallace, 1853; Haffer, 1974, 1978; Rego et al., 2023). Although its generality has been recently questioned (Oliveira et al., 2017; Santorelli et al., 2018; Ruokolainen et al., 2019; Dambros et al., 2020; Fluck et al., 2020), this remains a recurrent background for studies on evolution (e.g., Pirani et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2019), for conservation (e.g., Barlow et al., 2016; ICMBio, 2016), and for discoveries of new species (e.g., Roosmalen et al., 2002; Whitney and Cohn-Haft, 2013; Oliveira et al., 2020).

The distributions of numerous lowland birds, including floodplain specialists, however, are among potential exceptions to this general pattern. Roughly 15% of Amazonian birds are specialized on floodplain habitats (Remsen and Parker, 1983), including unique forest types and other vegetation physiognomies (Junk et al., 2011). For these species, distributions are commonly depicted as continuous along large rivers, including both margins (see, e.g., Ridgely and Tudor, 1994), which are not expected to differ in bird species composition. Recent field surveys and genetic analyses of floodplain birds support the frequent lack of differentiation on opposite river banks and suggest other geographic distribution patterns (Cohn-Haft et al., 2007; Choueri et al., 2017; Thom et al., 2018, 2020; Laranjeiras et al., 2019, 2021; Naka et al., 2020a,b). At least two distinct zones of endemism for floodplain avifauna were proposed along the main channel of the Amazon River (Cohn-Haft et al., 2007), and conspicuous species turnover was also noted between the upper and lower reaches of the Rio Branco in northern Brazil (Naka et al., 2020a). However, no thorough examination of distribution patterns throughout Amazonia exists for floodplain birds, limiting understanding of the spatial organization of Amazonian biodiversity and its evolution. From a conservation perspective, this is especially concerning, considering that floodplain habitats are under imminent threat due to land use changes and infrastructure development (Latrubesse et al., 2021).

Here we present the first analysis of distributions and endemism of floodplain birds for Amazonia, testing for the existence of areas of endemism and for a regionalization scheme (i.e., a classification of areas according species composition) that is distinct and complementary to the interfluvial pattern. We gathered and revised occurrence records for a comprehensive list of floodplain specialized birds, generated updated range maps, and analyzed them using two complementary techniques. We discuss how current environmental factors and potential historical processes may have shaped these patterns, considering the natural history and systematic relationships of the endemic taxa, and their implications for conservation strategies.

Materials & methodsWe analyzed the geographic distributions of floodplain specialized birds within Amazonia as defined by Eva et al. (2005). We first compiled a list of such birds (Table S1), based mainly on previous lists provided by Remsen and Parker (1983) and Parker et al. (1996), and our own field data and experience. We ran our analyses on two data sets of floodplain specialist bird taxa (following the taxonomy of Pacheco et al. (2021)): one at species level and another considering subspecies (or populations) from selected species as unique taxa. For the second approach we considered as unique taxa mainly the subspecies that presented disjunct distributions, but also Amazonian populations from species that also occur outside the biome. The criterion for subspecies identification was geographic, using the description of subspecies ranges from Billerman et al. (2022), with some adjustments. We then assembled occurrence records for each floodplain bird specialist taxon to generate accurate range maps. Up to 2019, we obtained data from numerous sources, including mainly museum collections, collaborative on-line platforms, and our own field observations (see Table S2). Data were cleaned for duplicates and resulting maps of occurrence records were inspected to detect inconsistencies. In this step, we removed undocumented records (not linked to a skin, photo, voice record, or detailed description) when they were outside the previously known range or the range based on documented records, or in an area without suitable habitat.

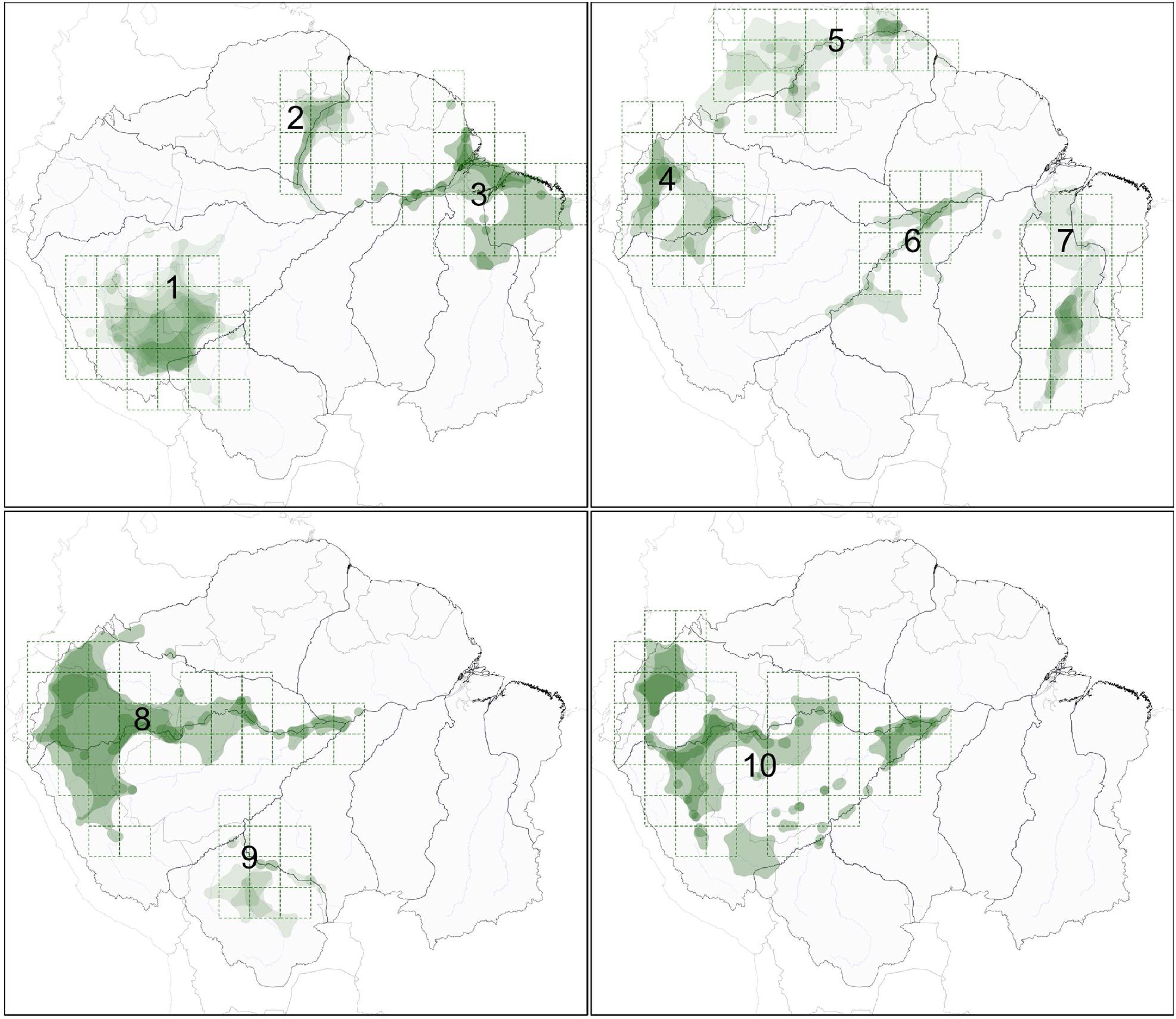

Recognizing areas of endemismWe searched for areas of endemism (sensuPlatnick, 1991), or groups of species with congruent distributions, using the heuristic algorithm of ndm/vndm (version 3.1) that is based on an optimality criterion (Goloboff, 2001; Szumik and Goloboff, 2004). The ndm-vndm is a grid-based exploratory algorithm that evaluates spatial concordance regarding the presence of two or more taxa for a given set of grid cells, generating a score of endemicity for a given taxon according to how its distribution corresponds to that set of cells. For this analysis, individual distributions were transformed in grid-based species presence-absence matrices, with variable cell sizes (0.5°, 1.0°, and 2.0°) and position of the grid, enabling detection of areas of endemism at variable levels of congruence in species distribution. Searches were performed with default settings, repeated 100 times, saving subsets with scores above 2.0, with two or more endemic species scoring at least 0.4, and assuming occurrence in adjacent cells if records were near the cell border (25% of the respective cell size). Finally, consensus sets of cells were identified with the cut-off at 25% similarity in endemic species, through the “consensus flexible” criterion, to avoid having the same species representing two or more areas, without merging only slightly overlapped areas. To visualize the identified areas of endemism (consensus areas), we superimposed the respective set of cells with the alpha-hull polygons of endemic taxa, highlighting more precisely the area of overlap.

We generated alpha-hull polygons, using the EOO.computing function of the ConR R Package, version 1.2.3 (Dauby et al., 2017). In this step, we enclosed occurrence records (with buffer area of 0.3 degrees) in alpha-hull polygons, which removed large areas between remote records, according to the alpha parameter. Alpha was set at 1.5, which performed better in dealing with distinct distributions of occurrence records among species.

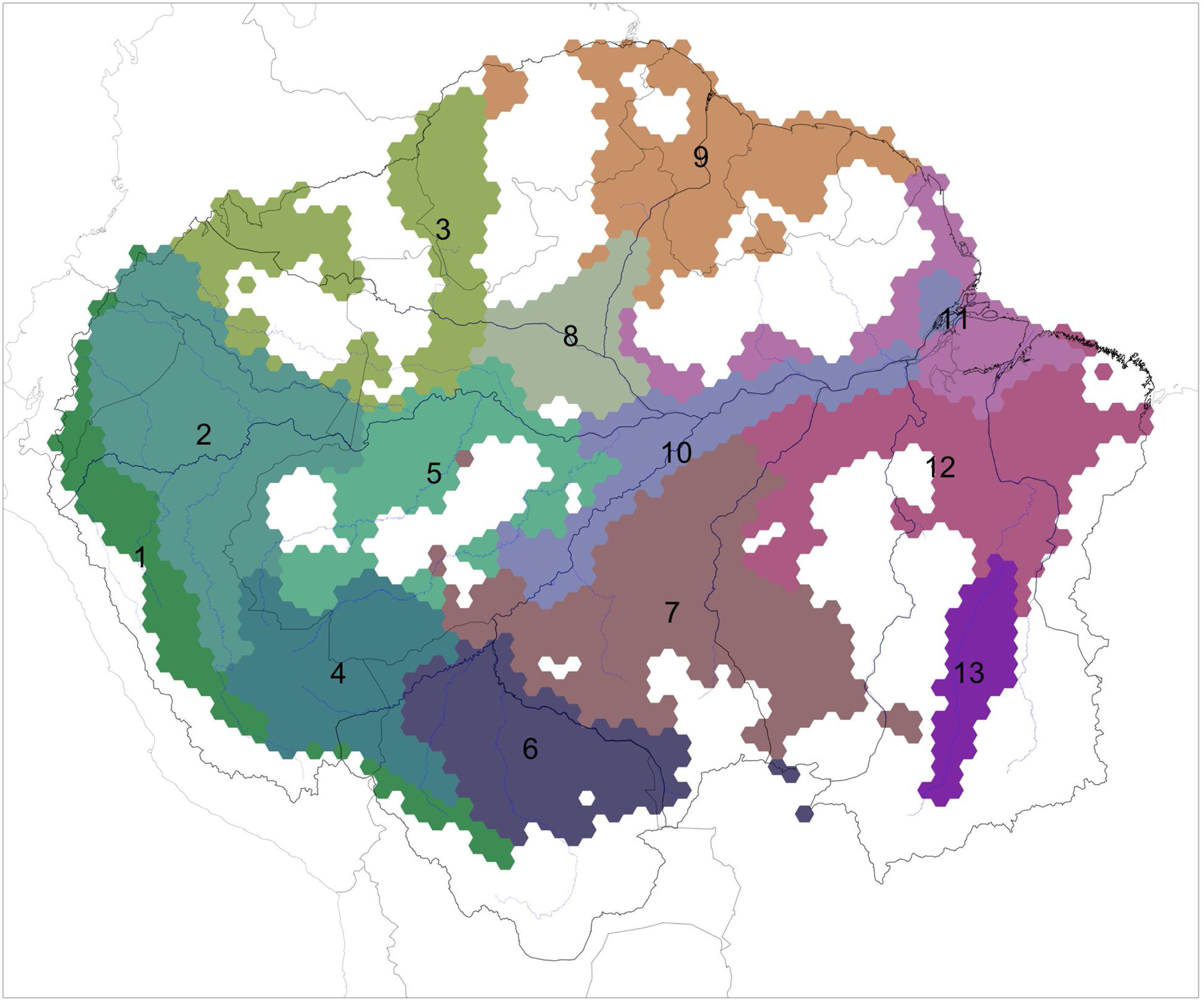

RegionalizationTo retrieve a potential subdivision of Amazonia (i.e., a classification of areas according species composition), based on the combined distributions of floodplain specialist birds, we used a grid-based clustering algorithm: the recluster.region (Dapporto et al., 2013), available in the recluster R package (Dapporto et al., 2015). In this analysis, we used the alpha-hull polygons to represent species distributions. Also, grid cell size was 0.5 degrees and grid cells with less than 10 taxa were excluded from the analysis. This algorithm is designed to identify regions grouping grid cells with high similarity in species composition through a kind of permutational hierarchical clustering. This clustering procedure avoids the effects of the order of the cells, in the original presence-absence matrix, on the topology and bootstrap support of the dendrograms by randomly reordering the cells in the original dissimilarity matrix. The similarity between pairs of grid cells was calculated using the Jaccard index (dissimilarity). The best clustering solution was identified for the regionalization (i.e., distribution and number of groups; here tested from two to twenty) that enhances the degree of explained dissimilarity between groups to over 0.9 (which ranges between 0 and 1) and indicates a stronger accuracy of classifying cells in the correct group (or mean silhouette), given all alternative cluster dendrograms, than the regionalization with one additional group (Holt et al., 2013; Godinho and Silva, 2018).

To identify which bird taxa characterized each identified region, we performed an Indicator Species Analysis on the same matrix, using the multipatt function of the indicspecies R package (De Cáceres and Jansen, 2015). This analysis generates a value between 0 and 1 for each species, where 0 indicates no association with either region, and 1 indicates both complete fidelity to one of the regions and presence in every cell in that region. Statistical significance of the indicator value was assessed through 1,000 permutations. Analyses allowed evaluation of the indicator value of each taxon for up to two regions.

ResultsWe generated range maps for 182 bird taxa (138 species, plus 44 additional subspecies or populations) that are specialized on Amazonian floodplain habitats (Table S1). Our database comprised more than 80 thousand unique records from multiple sources (Table S2).

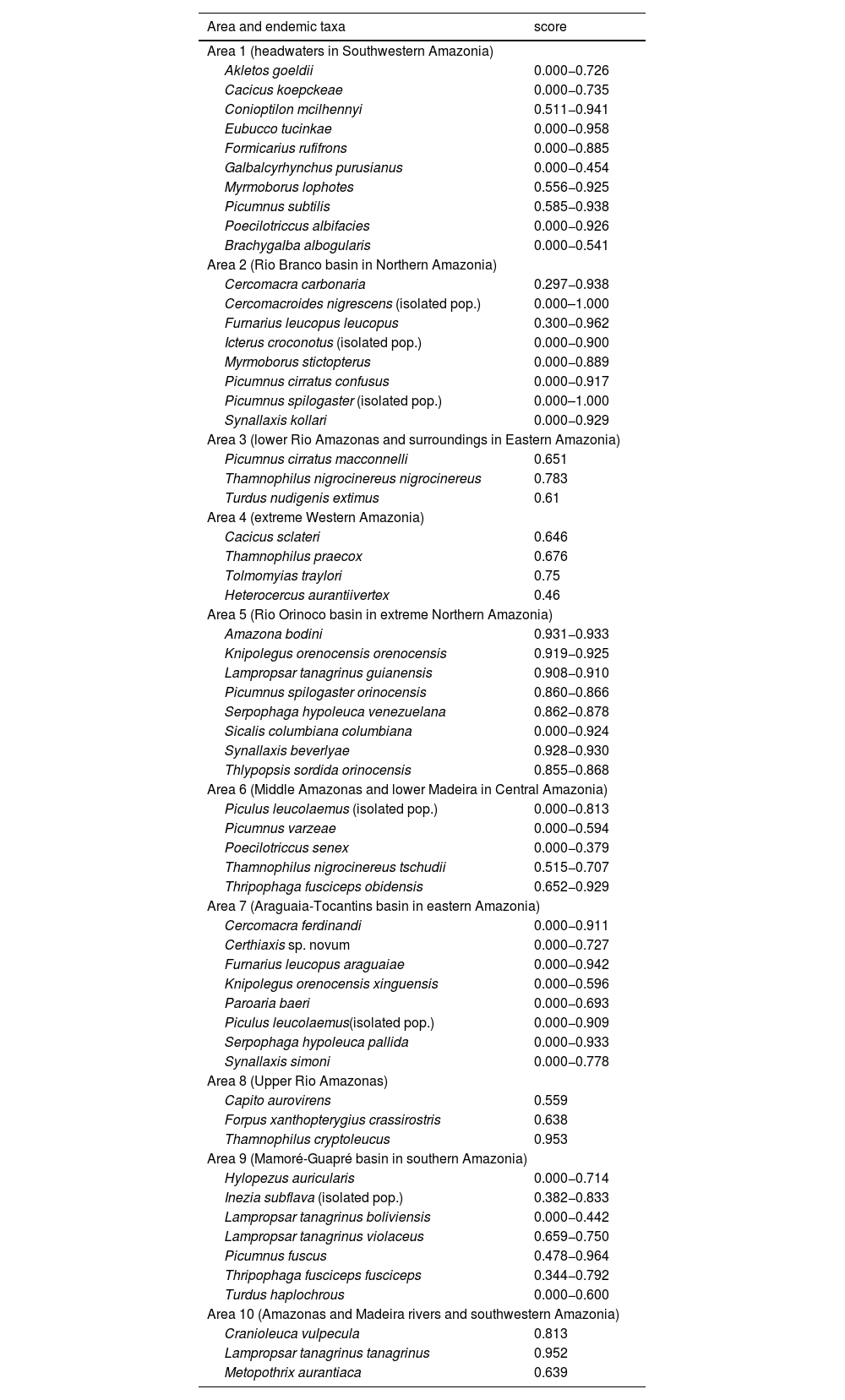

Exploratory searches, using the ndm/vndm grid-based heuristic algorithm, recognized ten potential areas of endemism (at two degrees of cell size), including one that encompassed only subspecies (Fig. 1, Table 1). No areas were recognized at 0.5 degrees of cell size and only two (areas 1 and 2) were recognized at one degree. From three to ten bird taxa characterized each potential area, totaling 59 endemics. None of the potential areas identified matched with interfluvial regions. Rather, major rivers were segmented into areas of endemism that were more aligned along their courses, where distributions of endemic species included both banks. Additionally, some areas of endemism were nested (e.g., areas 4, 8 and 10) or partially overlapped each other (e.g., 3 and 7, or 6 and 8). A similar structure emerged from individual distributions of endemic taxa within each area (e.g., area 1 or area 2).

Areas of endemism for Amazonian floodplain birds, as identified by the ndm-vndm algorithm, given 2 degrees of cell size (dashed grids). Polygons in green represent the individual distributions (alpha-hull polygons) of each endemic taxa (see Table 1), and the darkest areas show where ranges are superimposed. Black lines represent the limits of major interfluvial regions within the biome and gray lines are country boundaries.

Bird taxa that were identified as endemic to each area of endemism within Amazonian floodplains.

| Area and endemic taxa | score |

|---|---|

| Area 1 (headwaters in Southwestern Amazonia) | |

| Akletos goeldii | 0.000−0.726 |

| Cacicus koepckeae | 0.000−0.735 |

| Conioptilon mcilhennyi | 0.511−0.941 |

| Eubucco tucinkae | 0.000−0.958 |

| Formicarius rufifrons | 0.000−0.885 |

| Galbalcyrhynchus purusianus | 0.000−0.454 |

| Myrmoborus lophotes | 0.556−0.925 |

| Picumnus subtilis | 0.585−0.938 |

| Poecilotriccus albifacies | 0.000−0.926 |

| Brachygalba albogularis | 0.000−0.541 |

| Area 2 (Rio Branco basin in Northern Amazonia) | |

| Cercomacra carbonaria | 0.297−0.938 |

| Cercomacroides nigrescens (isolated pop.) | 0.000–1.000 |

| Furnarius leucopus leucopus | 0.300−0.962 |

| Icterus croconotus (isolated pop.) | 0.000−0.900 |

| Myrmoborus stictopterus | 0.000−0.889 |

| Picumnus cirratus confusus | 0.000−0.917 |

| Picumnus spilogaster (isolated pop.) | 0.000–1.000 |

| Synallaxis kollari | 0.000−0.929 |

| Area 3 (lower Rio Amazonas and surroundings in Eastern Amazonia) | |

| Picumnus cirratus macconnelli | 0.651 |

| Thamnophilus nigrocinereus nigrocinereus | 0.783 |

| Turdus nudigenis extimus | 0.61 |

| Area 4 (extreme Western Amazonia) | |

| Cacicus sclateri | 0.646 |

| Thamnophilus praecox | 0.676 |

| Tolmomyias traylori | 0.75 |

| Heterocercus aurantiivertex | 0.46 |

| Area 5 (Rio Orinoco basin in extreme Northern Amazonia) | |

| Amazona bodini | 0.931−0.933 |

| Knipolegus orenocensis orenocensis | 0.919−0.925 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus guianensis | 0.908−0.910 |

| Picumnus spilogaster orinocensis | 0.860−0.866 |

| Serpophaga hypoleuca venezuelana | 0.862−0.878 |

| Sicalis columbiana columbiana | 0.000−0.924 |

| Synallaxis beverlyae | 0.928−0.930 |

| Thlypopsis sordida orinocensis | 0.855−0.868 |

| Area 6 (Middle Amazonas and lower Madeira in Central Amazonia) | |

| Piculus leucolaemus (isolated pop.) | 0.000−0.813 |

| Picumnus varzeae | 0.000−0.594 |

| Poecilotriccus senex | 0.000−0.379 |

| Thamnophilus nigrocinereus tschudii | 0.515−0.707 |

| Thripophaga fusciceps obidensis | 0.652−0.929 |

| Area 7 (Araguaia-Tocantins basin in eastern Amazonia) | |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | 0.000−0.911 |

| Certhiaxis sp. novum | 0.000−0.727 |

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | 0.000−0.942 |

| Knipolegus orenocensis xinguensis | 0.000−0.596 |

| Paroaria baeri | 0.000−0.693 |

| Piculus leucolaemus(isolated pop.) | 0.000−0.909 |

| Serpophaga hypoleuca pallida | 0.000−0.933 |

| Synallaxis simoni | 0.000−0.778 |

| Area 8 (Upper Rio Amazonas) | |

| Capito aurovirens | 0.559 |

| Forpus xanthopterygius crassirostris | 0.638 |

| Thamnophilus cryptoleucus | 0.953 |

| Area 9 (Mamoré-Guapré basin in southern Amazonia) | |

| Hylopezus auricularis | 0.000−0.714 |

| Inezia subflava (isolated pop.) | 0.382−0.833 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus boliviensis | 0.000−0.442 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus violaceus | 0.659−0.750 |

| Picumnus fuscus | 0.478−0.964 |

| Thripophaga fusciceps fusciceps | 0.344−0.792 |

| Turdus haplochrous | 0.000−0.600 |

| Area 10 (Amazonas and Madeira rivers and southwestern Amazonia) | |

| Cranioleuca vulpecula | 0.813 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus tanagrinus | 0.952 |

| Metopothrix aurantiaca | 0.639 |

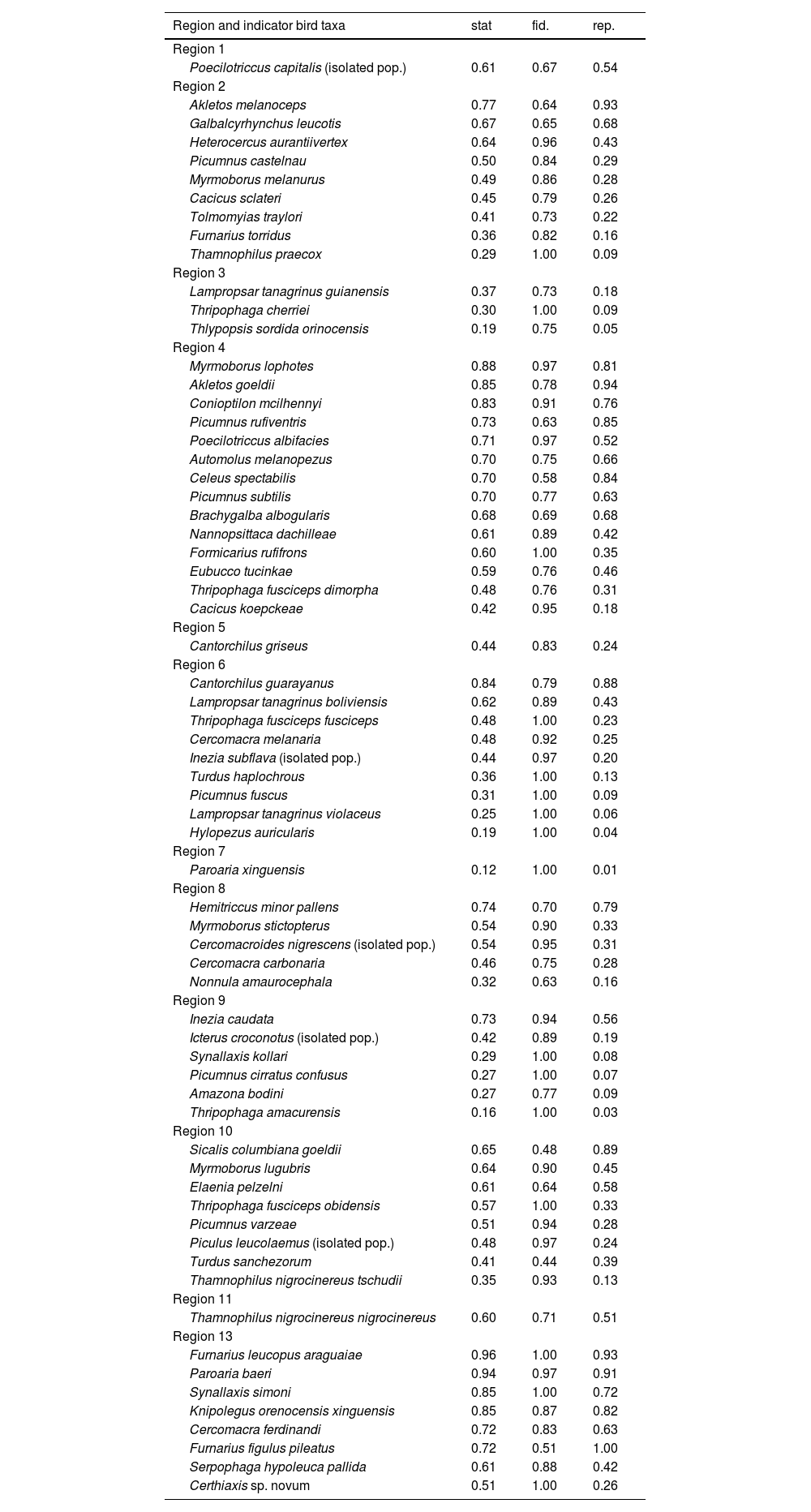

The clustering grid-based analysis (recluster.region algorithm) indicated a regionalization with 13 regions as the best solution for floodplain birds within Amazonia (Fig. 2, Fig. S1, Table S3). Indicator bird taxa were identified for all regions (except region 12), totaling 66 indicators (Table 2). A similar solution with 12 regions (Fig. S2) was recovered when analyzing distributions at species level (138 species). Regionalization reflected the identified areas of endemism (e.g., area 1 corresponded to region 4; area 6 to region 10). Similarly, none of the regions corresponded to interfluves.

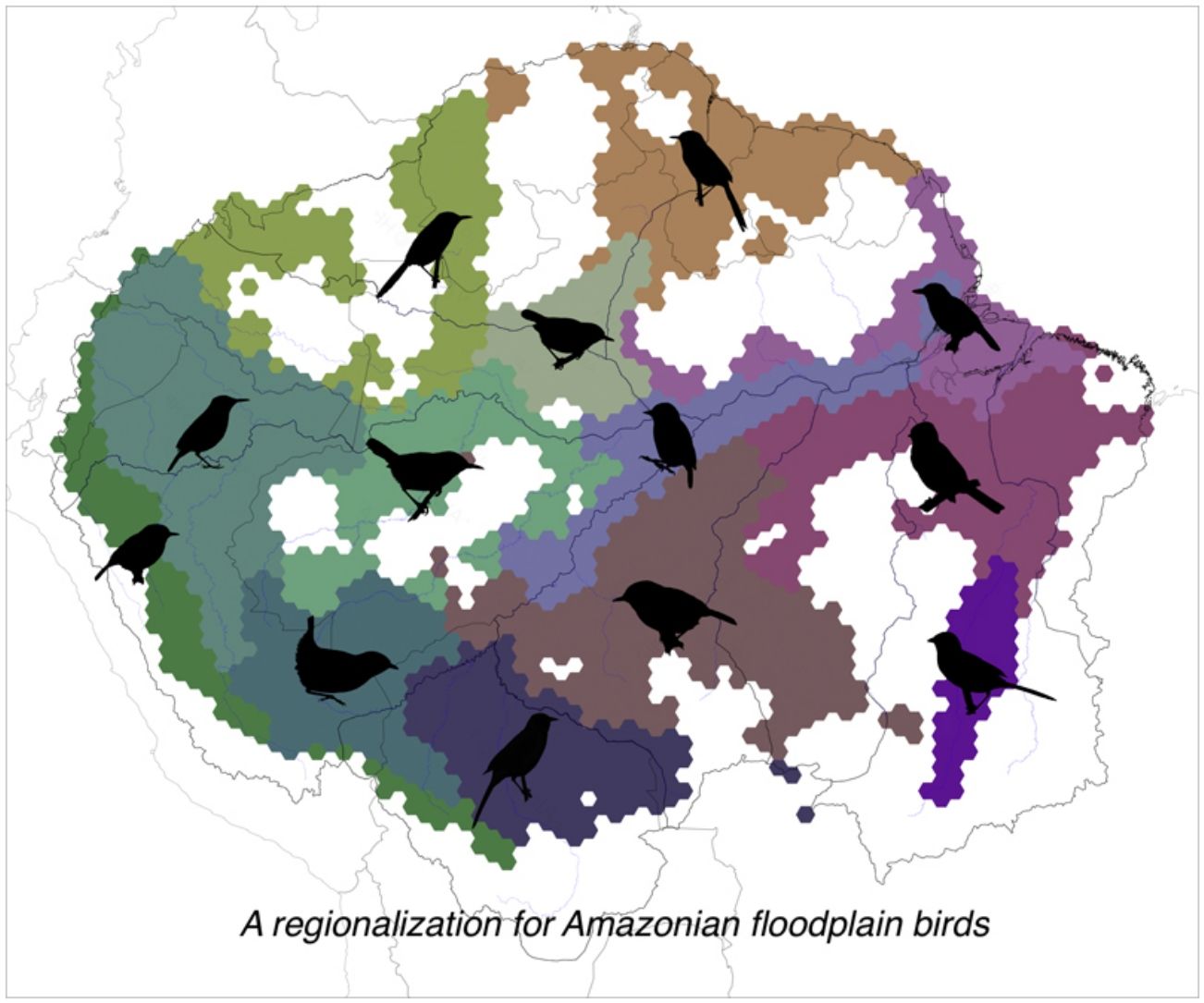

A regionalization of Amazonia based on the distributions of floodplain specialized birds. Indicator bird taxa of each region are listed in Table 2. White areas within Amazonia are cells occupied by less than 10 taxa and so were not included in the analyses. Black lines represent the limits of major interfluvial regions within the biome and gray lines are country boundaries. Similar colors between regions reflect species composition similarity.

Indicator bird taxa of the distinct regions that were identified by recluster.region algorithm for the Amazonian floodplains, including their indicator value (stat), the fidelity to the region (fid.) and representativeness in that region (rep.). Statistical significance of the indicator value is lower than 0.05 for all listed taxa.

| Region and indicator bird taxa | stat | fid. | rep. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | |||

| Poecilotriccus capitalis (isolated pop.) | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.54 |

| Region 2 | |||

| Akletos melanoceps | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.93 |

| Galbalcyrhynchus leucotis | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.68 |

| Heterocercus aurantiivertex | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.43 |

| Picumnus castelnau | 0.50 | 0.84 | 0.29 |

| Myrmoborus melanurus | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.28 |

| Cacicus sclateri | 0.45 | 0.79 | 0.26 |

| Tolmomyias traylori | 0.41 | 0.73 | 0.22 |

| Furnarius torridus | 0.36 | 0.82 | 0.16 |

| Thamnophilus praecox | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

| Region 3 | |||

| Lampropsar tanagrinus guianensis | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.18 |

| Thripophaga cherriei | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

| Thlypopsis sordida orinocensis | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.05 |

| Region 4 | |||

| Myrmoborus lophotes | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.81 |

| Akletos goeldii | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.94 |

| Conioptilon mcilhennyi | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.76 |

| Picumnus rufiventris | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.85 |

| Poecilotriccus albifacies | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.52 |

| Automolus melanopezus | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Celeus spectabilis | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

| Picumnus subtilis | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.63 |

| Brachygalba albogularis | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| Nannopsittaca dachilleae | 0.61 | 0.89 | 0.42 |

| Formicarius rufifrons | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.35 |

| Eubucco tucinkae | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.46 |

| Thripophaga fusciceps dimorpha | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.31 |

| Cacicus koepckeae | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.18 |

| Region 5 | |||

| Cantorchilus griseus | 0.44 | 0.83 | 0.24 |

| Region 6 | |||

| Cantorchilus guarayanus | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.88 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus boliviensis | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.43 |

| Thripophaga fusciceps fusciceps | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| Cercomacra melanaria | 0.48 | 0.92 | 0.25 |

| Inezia subflava (isolated pop.) | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.20 |

| Turdus haplochrous | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.13 |

| Picumnus fuscus | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

| Lampropsar tanagrinus violaceus | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Hylopezus auricularis | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.04 |

| Region 7 | |||

| Paroaria xinguensis | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| Region 8 | |||

| Hemitriccus minor pallens | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.79 |

| Myrmoborus stictopterus | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.33 |

| Cercomacroides nigrescens (isolated pop.) | 0.54 | 0.95 | 0.31 |

| Cercomacra carbonaria | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.28 |

| Nonnula amaurocephala | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.16 |

| Region 9 | |||

| Inezia caudata | 0.73 | 0.94 | 0.56 |

| Icterus croconotus (isolated pop.) | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.19 |

| Synallaxis kollari | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.08 |

| Picumnus cirratus confusus | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.07 |

| Amazona bodini | 0.27 | 0.77 | 0.09 |

| Thripophaga amacurensis | 0.16 | 1.00 | 0.03 |

| Region 10 | |||

| Sicalis columbiana goeldii | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.89 |

| Myrmoborus lugubris | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.45 |

| Elaenia pelzelni | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.58 |

| Thripophaga fusciceps obidensis | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.33 |

| Picumnus varzeae | 0.51 | 0.94 | 0.28 |

| Piculus leucolaemus (isolated pop.) | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.24 |

| Turdus sanchezorum | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.39 |

| Thamnophilus nigrocinereus tschudii | 0.35 | 0.93 | 0.13 |

| Region 11 | |||

| Thamnophilus nigrocinereus nigrocinereus | 0.60 | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| Region 13 | |||

| Furnarius leucopus araguaiae | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.93 |

| Paroaria baeri | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.91 |

| Synallaxis simoni | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.72 |

| Knipolegus orenocensis xinguensis | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| Cercomacra ferdinandi | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| Furnarius figulus pileatus | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.00 |

| Serpophaga hypoleuca pallida | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.42 |

| Certhiaxis sp. novum | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.26 |

Previously recognized areas of endemism in Amazonia have had a central role in understanding and conservation of the biome’s biodiversity (Silva et al., 2005; Cracraft et al., 2020). Here, based on updated and revised distributions of a representative proportion of bird species specialized on floodplain habitats, we unveiled a complementary set of areas and a habitat-specific regionalization of the biome. For the floodplain birds, Amazonian major rivers are segmented into distinct areas of endemism rather than these areas being delimited by the rivers. The well-established subdivision of Amazonia in large interfluvial areas is appropriate for terra firme birds (Naka, 2011; Silva et al., 2019), but fails to account for taxa associated with floodplain habitats. Thus, these parallel, complementary, and somewhat overlapped habitat-specific regionalizations are consistent with the view of Amazonia as an intricate mosaic of ecoregions (Olson et al., 2001; Goulding et al., 2003), and help to better comprehend the distribution of the region's extraordinary diversity.

Our results underline the importance of identifying major habitat affinities for a more comprehensive biogeographical characterization of Amazonia. In part, perhaps, the higher number of bird species associated with the predominant terra firme forests (Stotz et al., 1996) may have prevailed historically, hiding the relatively fewer floodplain specialists, which may have been regarded as “noise” relative to areas of endemism with clear riverine boundaries (see Haffer, 1978; Cracraft, 1985). Because rivers are obvious features within the vast forested landscape of Amazonia, it is almost unavoidable to tie species distributions to them. But whether rivers delimit species’ distributions or define them appears to depend on habitat use, which is a species-specific characteristic. Further complicating pattern recognition, areas flooded by different water types contain distinct avifaunas (Laranjeiras et al., 2019). Thus, floodplains along major whitewater rivers in Central Amazonia, which are flanked by the floodplains of only black- or clearwater tributaries (see Hess et al., 2015; Venticinque et al., 2016), will give the impression of a river delimited distribution for those floodplain species that do not occur along the main (whitewater) Amazon. This may have created the impression of river-delimitation in some floodplain birds for previous biogeographers. By focusing our analyses on the floodplain specialists, we could disentangle the coincidence of river presence with differences in water type. Prior analyses (e.g., Oliveira et al., 2017; Fluck et al., 2020) may have missed the patterns we found here due to imprecise or incomplete occurrence data (Zizka et al., 2020; Rego et al., 2023).

Our regionalization includes overall concordances with recent findings from field surveys. The zones of endemism along the mainstem Amazon River (Solimões-Amazonas) in Brazil proposed by Cohn-Haft et al. (2007) were recovered here. Our results support a biogeographic subdivision along the river, with a transition near its confluences with the Negro and Madeira rivers. This transition itself was recovered as an area of endemism (area 6), including species occurring on the lower Madeira. Two distinct regions along the Rio Branco (Naka et al., 2020a) were also supported. Although the Rio Branco itself was recognized as an area of endemism (area 2), its upper reach is associated with the floodplains to the north, including the Rio Orinoco, whereas its lower portion joins with the Rio Negro, likely reflecting their confluence (Laranjeiras et al., 2021). Another region, covering the headwaters of rivers in southwestern Amazonia (including the Purus, Juruá, and Ucayali), may represent a more general biogeographical pattern, not restricted to the floodplains, that has also been observed in plants (Tuomisto et al., 2016) and anurans (Godinho and Silva, 2018), although it went unnoticed or unreported for birds in a biogeographical study along the Ucayali River (Harvey et al., 2014).

Despite these overall concordances, given the resolution of our analyses (from 0.5 to 2 degrees), the limits of the identified areas were more blurred and therefore should not be interpreted as absolute. Considering the nestedness and partial overlap of the identified areas and regions, there is probably a more continuous variation in species composition along rivers. Thus, defining abrupt limits may not be appropriate for Amazonian floodplains, in contrast to the clear-cut limits represented by the rivers themselves in the traditional terra firme areas of endemism. This is reasonable considering the lack of obvious physical barriers to dispersal along continuous floodplains. Yet finding any endemism in this continuous landscape is striking and suggests the action of important ecological and historical factors.

Natural history and systematic relationships of endemic bird taxa (see, e.g., Billerman et al., 2022) offer useful insights to understanding the geographic pattern described. Some endemic bird taxa are known to be associated with variants of floodplain forests or micro-habitats that are prominent in their area. In southwestern Amazonia (area 1; region 4), for example, most endemic birds are commonly associated with bamboo-dominated floodplain forests, which are regionally extensive (Smith and Nelson, 2011). Whereas in the Branco (area 2) or in the Araguaia-Tocantins basins (area 7; region 6), birds are usually linked to gallery forest within a savanna landscape (Junk et al., 2011). A few areas (see areas 4, 6 or 9 in Table 1), on the other hand, grouped taxa with different micro-habitat associations, linked mainly to water type, likely due to the coarse scale of analyses. Nevertheless, some of the endemic species are not replaced by a congener elsewhere, in contrast to the common pattern of geographical replacement for terra firme birds. This suggests that competition is not the factor limiting the geographic range of these floodplain endemics. Thus, given the tight association often found between birds and vegetation structure or physiognomy (Cody, 1985; and articles therein), distributions of floodplain specialists likely reflect the spatial distribution of the physiognomic variants of the floodplain habitats, a pattern analogous to what is found for Amazonian trees (Luize et al., 2024).

The absence of present-day barriers separating some congeneric taxa, on the other hand, suggests a role for past landscapes in creating these patterns. Large Amazonian rivers suffered recent modifications in their courses and in the extent of their floodplains (see e.g., Espurt et al., 2010; Cremon et al., 2016; Ruokolainen et al., 2019; Pupim et al., 2019; Sawakuchi et al., 2022). Quaternary climate changes likely promoted diversification in three floodplain bird species complexes, by triggering periodic habitat discontinuities in the floodplains of Central Amazonia (Thom et al., 2020). The current configuration of the drainage system is likely a recent feature of Amazonia and distributional ranges of floodplain-specialized birds should echo multiple and interacting factors in time and space.

Regardless of exact geographical limits and hypothesized explanations, our regionalization for the Amazonian floodplain birds is a new baseline for further research and conservation. Standardized avifaunal sampling in areas where limits were outlined here will indicate their nature, especially along poorly explored river sections (e.g., the lower Caquetá River, in Colombia, or the middle Xingu River, in Brazil; but see Carvalho et al. (2023)). Also, a number of specialized birds are polytypic species, and their phylogeographic relationships will shed light on past dynamics and interactions of the floodplains, as well as possibly revealing other areas of endemism within the floodplains. Additional analyses should estimate the importance of physiognomic variation of floodplain habitats and how this variation is associated with other aspects, such as water type (Laranjeiras et al., 2019, 2021), geomorphology (Sawakuchi et al., 2022; Schultz et al., 2024), or climate (Naka et al., 2020b). Further research on other groups of organisms with similar habitat associations will permit evaluation of the generality of the patterns described here.

For conservation purposes, some regions identified here need immediate attention. The floodplains of the Araguaia-Tocantins and middle Xingu rivers are already heavily impacted by deforestation (Latrubesse et al., 2009) and numerous hydroelectric dams (de Luca et al., 2009; Lees et al., 2016; Latrubesse et al., 2017). Belo Monte, one of the largest Amazonian dams, fragmented the Xingu River floodplain habitats and impacted a stretch of 130 km along the river with an artificially controlled permanent drought (Zuanon et al., 2019; Pezzuti et al., 2024). Endemic bird taxa and isolated populations in this region are likely the most threatened among all Amazonian floodplain birds. A similarly threatening future awaits endemic bird species in the Rio Branco basin, an expanding agricultural frontier in northern Brazilian Amazon (Barni et al., 2020), where a large dam is planned to be built soon (Naka et al., 2020a). Several other bird species with unique distributions along a single river (e.g., the Tapajós River) should also be on the radar of conservation actions. We hope our regionalization will be useful for research and conservation of Amazonian biodiversity.

Declaration of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We are grateful to the following people and institutions for providing data on species distributions: Alexandre Aleixo (Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém); Van Remsen, Robb Brumfield, Steven Cardiff and Marco Rêgo (Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University); Reinaldo Guedes (WikiAves); Joel Cracraft (American Museum of Natural History, New York); and the Collections Program of Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, our home institution. TOL’s field activities were supported by Diretoria de Pesquisa, Avaliação e Monitoramento da Biodiversidade of ICMBio (TOL grant number MPC-014.007),Rufford Foundation (TOL grant number19908-1), and Programa Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia (ARPA). TOL was also funded by a doctoral fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). CCR was funded by CNPq (311732/2020-8),FAPEAM(Chamada Internacional Biodiversa) and PEER/USAID (Co Ag AID-OAA-A-11-00012).

This is contribution 78 in the Amazonian Ornithology Technical Series of the INPA Zoological Collections Program.