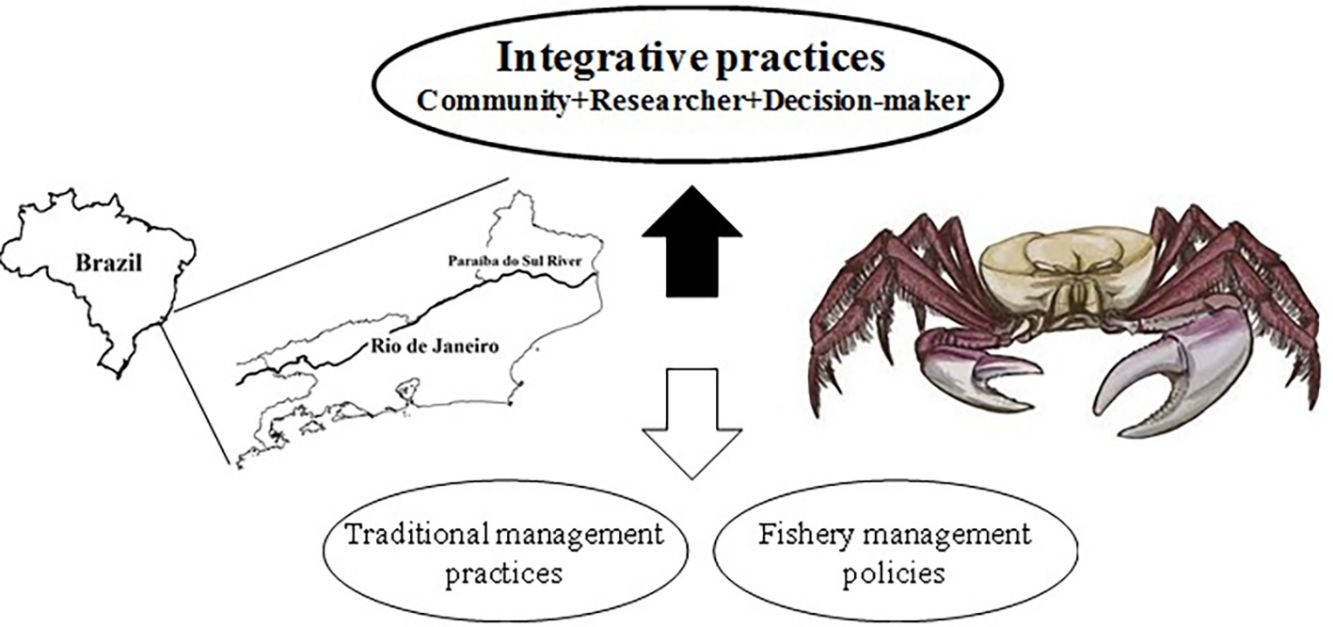

Mangrove ecosystems and their resources are important for traditional coastal communities. We analysed the efficiency of traditional management practices developed by crab (Ucides cordatus) gatherers in the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary (∼21°S), south-eastern Brazil, considering the carapace width of specimens harvested for commercial purposes in two different periods (2002–03 and 2015–16). The continuity of this crab harvest between 2002 and 2016 was likely possible because of decreased harvest pressure, which does not necessarily represent the traditional management efficiency needed to sustain this resource. Thus, this crab harvest system may be more fragile than expected by the local gatherers. Community-based proposals for the management of this U. cordatus harvest system, which integrate communities, researchers and decision-makers, can improve both local productivity and ecosystem-resource maintenance, mitigating local conflicts.

Mangroves are among the most productive ecosystems worldwide and occupy brackish water zones along tropical and subtropical coasts. This ecosystem has habitat functions for many organisms as fishes, crustaceans and molluscs and provides sediment trapping, nutrient recycling and protection of the shoreline from erosion (Barbier et al., 2011). However, since 1980, mangrove areas have been declining rapidly, becoming highly stressed forests with a global reduction of approximately 25% (FAO, 2007; Ahmed and Glaser, 2016). Mangrove products are important sources of income for traditional coastal communities. Fishing and related activities, such as the harvesting of crustaceans and bivalves, are generally the prime income-generating activities in these communities, which are generally economically depressed and marginal (FAO, 2007).

In general, traditional communities apply their local ecological knowledge (LEK) in exploitation practices and natural resource utilisation to develop traditional management methods (Côrtes et al., 2014a; Roy, 2016). Dimitrakopoulos et al. (2010) defined community-based conservation (CBC) as conservation strategies that emphasise the role of local communities as partners in management practices and decision-making. Thus, CBC should be by and for communities. The main reason for promoting CBC models is to achieve sustainable management, where traditional communities can manage and extract benefits from the locally available natural resources to improve their livelihoods and encourage a conservation attitude (Baral and Stern, 2011). In this sense, both researchers and decision-makers have advocated community-based mangrove management as a viable alternative for sustainably managing mangrove forests, with higher numbers of initiatives in South Asia and fewer in South America and Africa (Datta et al., 2012).

Considering the mangrove resources with commercial value to traditional communities, the crab Ucides cordatus Linnaeus, 1763 has economic prominence on the western Atlantic coast, especially along the Brazilian coast from 3°N to 27°S (e.g., Glaser and Diele, 2004; Côrtes et al., 2014a; Nascimento et al., 2017). According to the Brazilian policy that regulates the exploitation of this resource, the minimum size for U. cordatus harvest in Brazilian mangroves is 60mm of carapace width for both males and females. The legal requirements also exclude from commercial harvest females with eggs of any size and crabs during the ecdysis phase as well as the harvest during the crab's reproductive activity (Ministerial Order 52/30.09.2003, available at http://www.icmbio.gov.br/cepsul/images/stories/legislacao/Portaria/2003/p_ibama_52_2003_defesocaranguejouca_se_s.pdf).

The crab gatherers from northern Rio de Janeiro State (∼21°S), south-eastern Brazil, have developed traditional management practices to maintain the local viability of this economic activity (Rodrigues et al., 2000; Passos and Di Beneditto, 2005; Côrtes et al., 2014a). Two main management practices are employed by the local gatherers: (i) selection of crabs by sex and size, avoiding the commercialisation of females with eggs and smaller crabs of both sexes and (ii) rotation of the most exploited mangrove areas throughout the year. The crab harvest occurs during all months, decreasing during the breading season (October, November and December). The gatherers still use forbidden gear, as a net locally called ‘redinha’, which is prohibited by the Brazilian policy that regulates the U. cordatus exploitation (Côrtes et al., 2014b).

These gatherers harvest U. cordatus along the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary that is characterised mainly by Avicennia germinans [L.] Stearn. 1764 (53% of coverage), Laguncularia racemosa [L.] Gaertn f. 1807 (28%) and Rhizophora mangle L. 1753 (19%) (Bernini and Rezende, 2011). The harvest effort during the summer period (November to April, according to the gatherers) is greater in R. mangle forests, while in the winter (May to October, according to the gatherers) it is greater in A. germinans forests. Seasonal and spatial occurrence of larger crabs drive this practice. According to the gatherers, the ‘resting’ period of these mangrove forests contributes to the growth of the U. cordatus population, maintaining the resource for commercial harvest (Côrtes et al., 2014a).

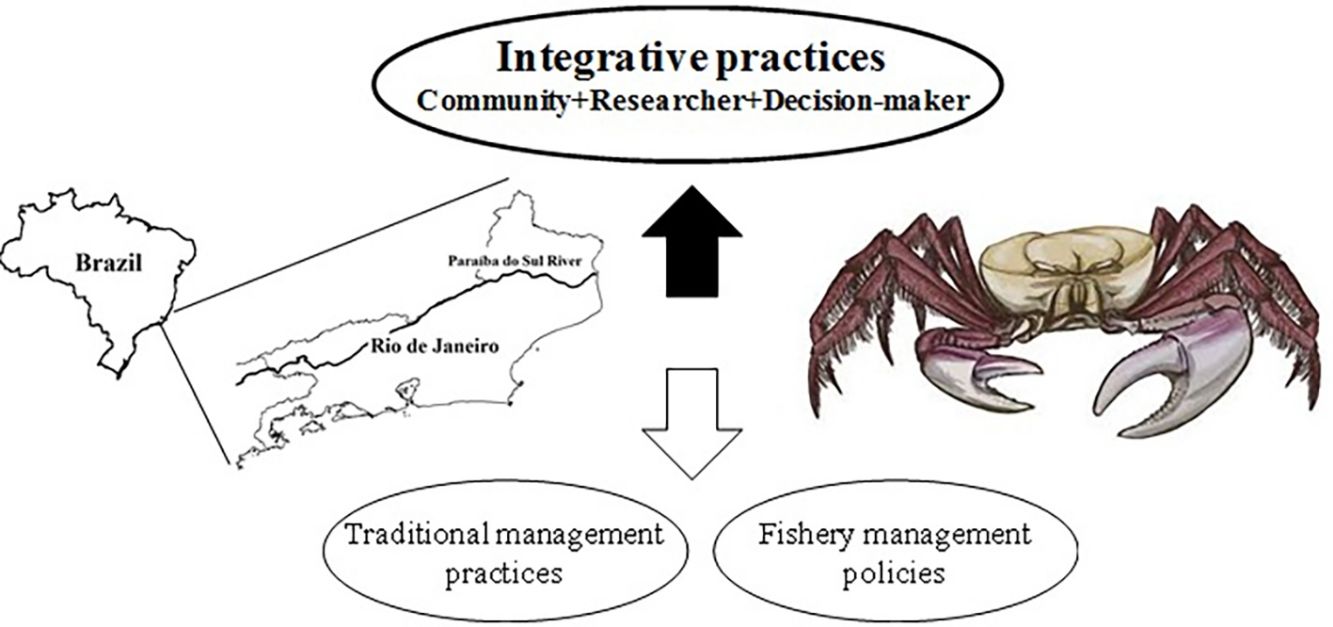

We argue whether the traditional management practices developed in this mangrove forest are sufficient to maintain the long-term crab harvest. Sustainability assessments of activities that involve natural resources exploitation include many variables, as social, cultural and economic characteristics of the communities as well as biological and ecological aspects of the resources or target species (Singh et al., 2009). This study considered only the size of the crabs available for commercialisation, considering the minimum size for U. cordatus harvest in Brazilian mangroves. The monitoring of this single variable (size) over the two periods (2002–03 and 2015–16) allows a rapid assessment of how the local crab population is structured against the pressure resulting from the commercial harvest. Size monitoring of target species is successfully used in fisheries management, supporting risk assessments of fishing impacts (Shin et al., 2005; Froese et al., 2008). Additionally, this study presents integrative strategies involving traditional communities, researchers and decision-makers to drive local management practices.

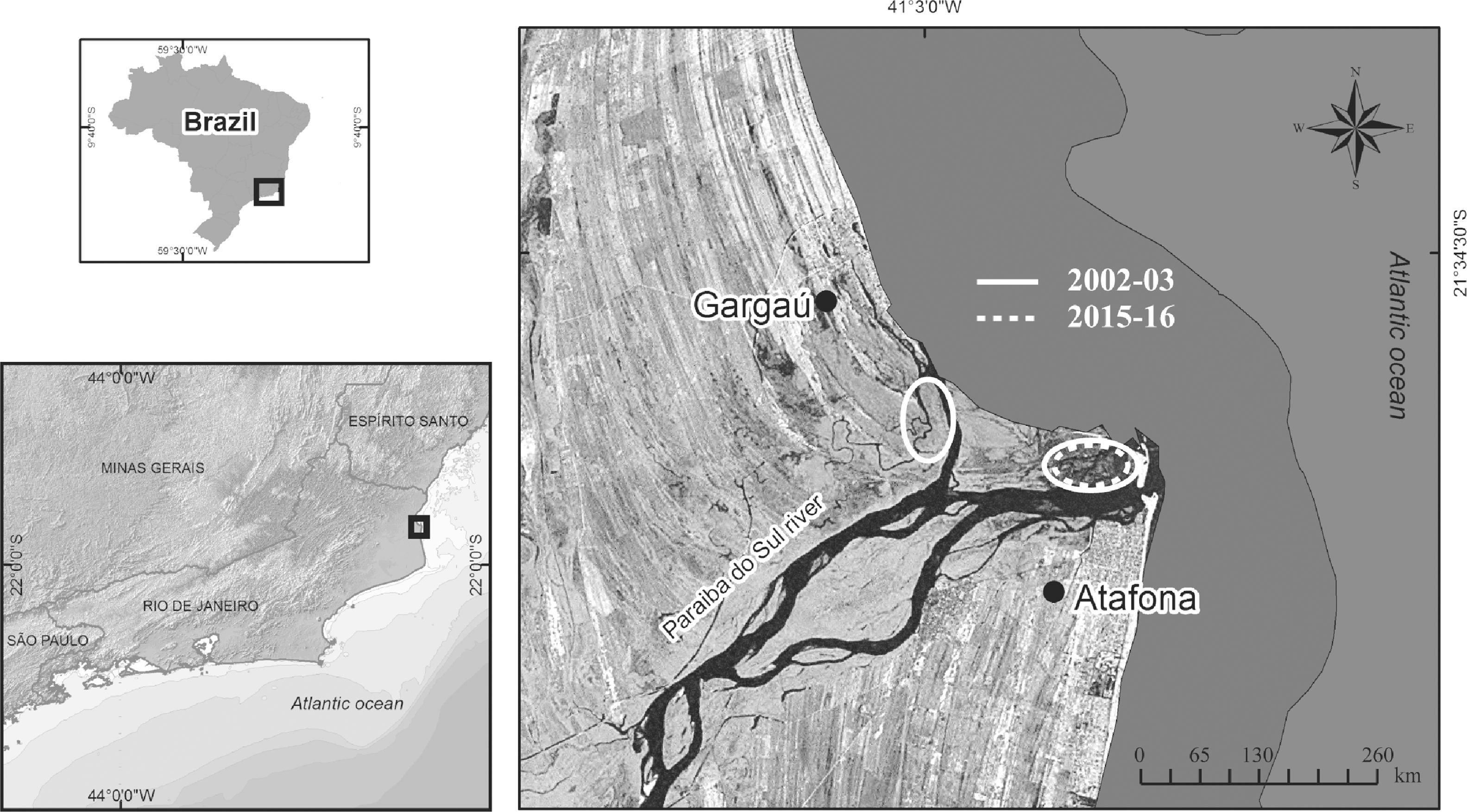

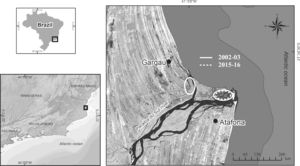

MethodsStudy siteThe study site is the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary (Fig. 1). The mangrove stand occupies approximately 725ha and lost more than 20% of its original area in 15 years (1986–2001) because of sedimentation, erosion, cattle grazing and urban development (Bernini, 2008). The traditional communities of Atafona and Gargaú have harvested crabs for decades in this mangrove forest, and gatherers from both communities share the harvest area (Fig. 1) (Rodrigues et al., 2000; Côrtes et al., 2014a). During our samplings, local gatherers described this activity as having occurred in the region for more than 100 years.

Local crab gatherers are members of Fishermen's Colony Z-2 (Atafona) and Colony Z-1 (Gargaú). Before 2012, at least 46 gatherers from Atafona and 50 from Gargaú participated in the crab harvest in this mangrove forest (Côrtes et al., 2014b). In 2012, the number of gatherers decreased in Atafona (n=16), but remained constant in Gargaú (n=50) (Côrtes et al., 2014a). In 2015, only six gatherers from Atafona participated in the crab harvest, while the number remained constant in Gargaú (present study).

Data collectionThe crab specimens were collected, cleaned in the river water to remove the mud excess, separated as male or female, measured for carapace width with a vernier caliper (1mm) and grouped into two sampling periods: (i) 2002–03 and (ii) 2015–16.

In the first sampling period, the specimens were obtained monthly, directly from the gatherers in local markets (commercialised crabs), except during the months determined by law for the closure of crab gathering in the region (October to December). In this sampling, the crabs were previously selected by size: the gatherers released alive in the mangrove, before the commercialisation, smaller crabs of both sexes (Passos and Di Beneditto, 2005; Côrtes et al., 2014a).

In the last period, the sampling was done throughout the mangrove forest with the collaboration of the same local gatherer for three consecutive days in September 2015 and in March 2016. This sampling was done biannually, as suggested by Pinheiro and Almeida (2015). The crab sampling was done along the three types of vegetation (A. germinans, L. racemosa and R. mangle) that are normally used as harvest areas during the commercial captures.

The harvest area used by the gatherers from Atafona and Gargaú overlaps, and is mainly along the islands located in the inner estuary of the Paraíba do Sul River (Fig. 1). The loss of the original mangrove area reported by Bernini (2008) occurred mainly in the continental portion. The crab samplings in both periods were in overlapping or close areas.

In the study site, the net referred to as ‘redinha’ is the main gear for harvesting crabs, composed of a monofilament net 50m long, 40cm high and with 8cm mesh between adjacent knots. The local gatherers use this gear for more than 30 years (Côrtes et al., 2014b). The crabs from 2002–03 sampling were caught by this gear (Passos and Di Beneditto, 2005).

In 2015–16, ‘redinha’ was also used to catch the crabs. The net was positioned over the openings of the crabs’ burrows in the substrate, which is the typical practice during the regular commercial harvest (Côrtes et al., 2014a), remaining for two hours in each mangrove vegetation type (A. germinans, L. racemosa and R. mangle). This sampling collected crab specimens eligible for commercial harvest; however, the size selection was achieved only by the gear and not subsequently by the gatherer as in the other sampling period (2002–03). All specimens captured during the 2015–16 sampling were released alive in the same sampling site immediately after carapace measurement.

Data analysisThe carapace width data were tested for normality using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As the data did not meet the statistical assumptions required for the use of parametric methods, a Mann–Whitney U-Test was applied to test for differences between sex and sampling periods. Despite the sexual dimorphism in carapace size, with males being larger than females (Pinheiro et al., 2005; Costa et al., 2014), the minimum size for U. cordatus harvest in Brazilian mangroves is the same for both sexes (60mm of carapace width). In the study site, the gatherers catch and commercialise both males and females (Côrtes et al., 2014a).

The statistical analysis employed Statistica 12.0 for Windows. The P value was interpreted as the strength of evidence for the null hypotheses rather than for the dichotomous scale of significance testing (Hurlbert and Lombardi, 2009).

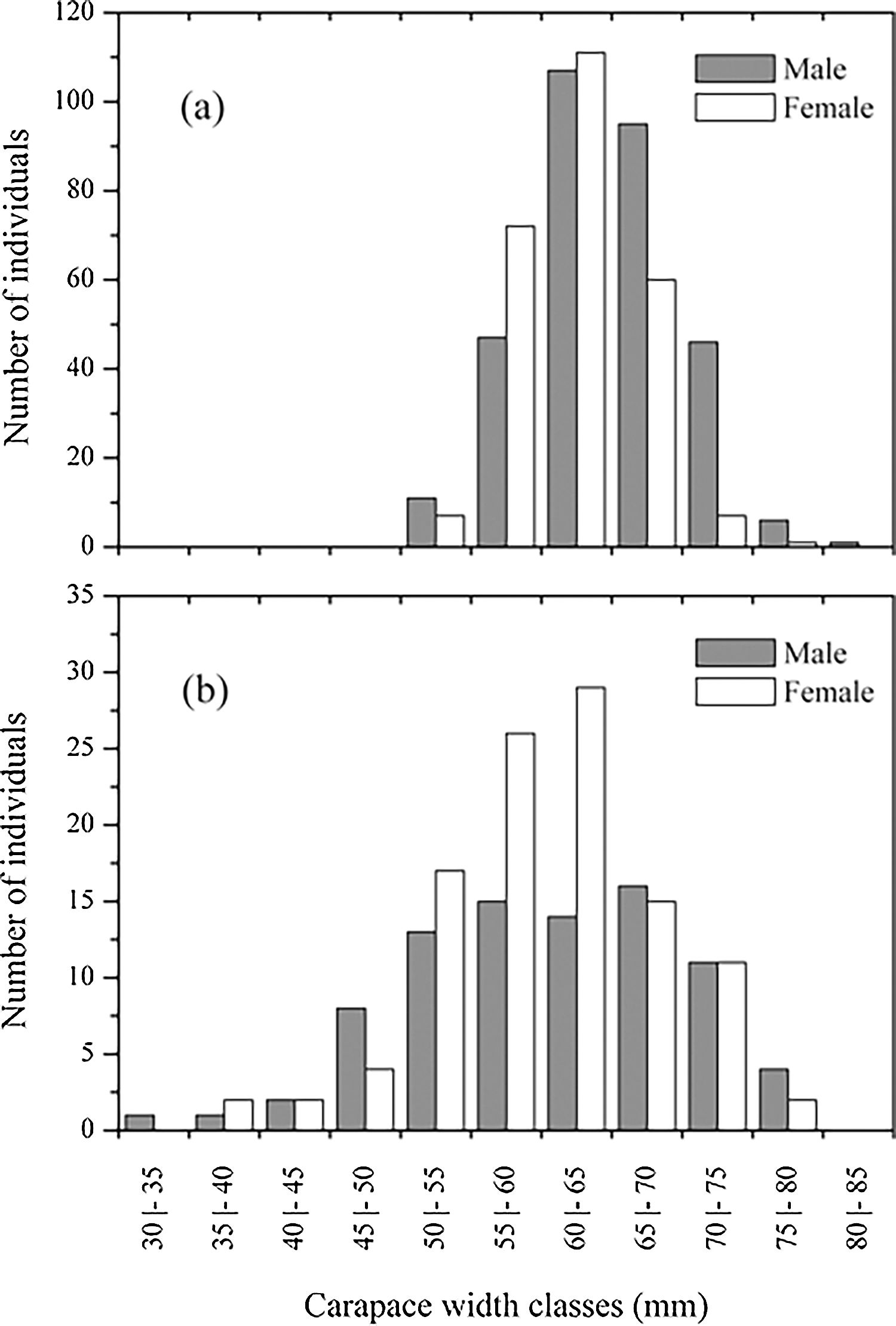

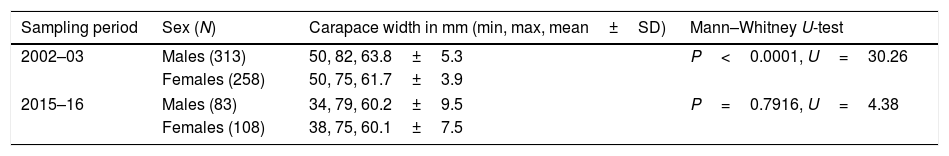

Results and discussionThe number of U. cordatus specimens considered in each sampling period was 571 in 2002–03 and 199 in 2015–16. The carapace size distribution according to sex and sampling periods is shown in Fig. 2. Mann–Whitney U-test revealed differences between males and females in 2002–03, with larger carapace sizes for males, while in 2015–16 the sizes were comparable between sexes (Table 1). Considering the males harvested in both periods, smaller animals were recorded during 2015–16 (P=0.002; U=10.11), and the same pattern was noted for the females (P=0.027; U=11.89).

Data about the Ucides cordatus specimens caught in mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary, south-eastern Brazil.

| Sampling period | Sex (N) | Carapace width in mm (min, max, mean±SD) | Mann–Whitney U-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002–03 | Males (313) | 50, 82, 63.8±5.3 | P<0.0001, U=30.26 |

| Females (258) | 50, 75, 61.7±3.9 | ||

| 2015–16 | Males (83) | 34, 79, 60.2±9.5 | P=0.7916, U=4.38 |

| Females (108) | 38, 75, 60.1±7.5 | ||

The mean carapace width of the U. cordatus specimens harvested for commercial purposes in the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary is close to the limit allowed by the Brazilian policy that regulates the exploitation of this resource (60mm), indicating the scarcity of large crabs in this population for at least 14 years (2002–2016). The crab's size in this mangrove is similar to other mangrove areas along the Brazilian coast (Costa et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2016). The growth rate of crustaceans (and its size) is affected not only by the catch pressure (Biro and Sampson, 2015), but also by the environmental factors such as food availability, temperature and salinity (Pinheiro and Hattori, 2006; Diele and Koch, 2010).

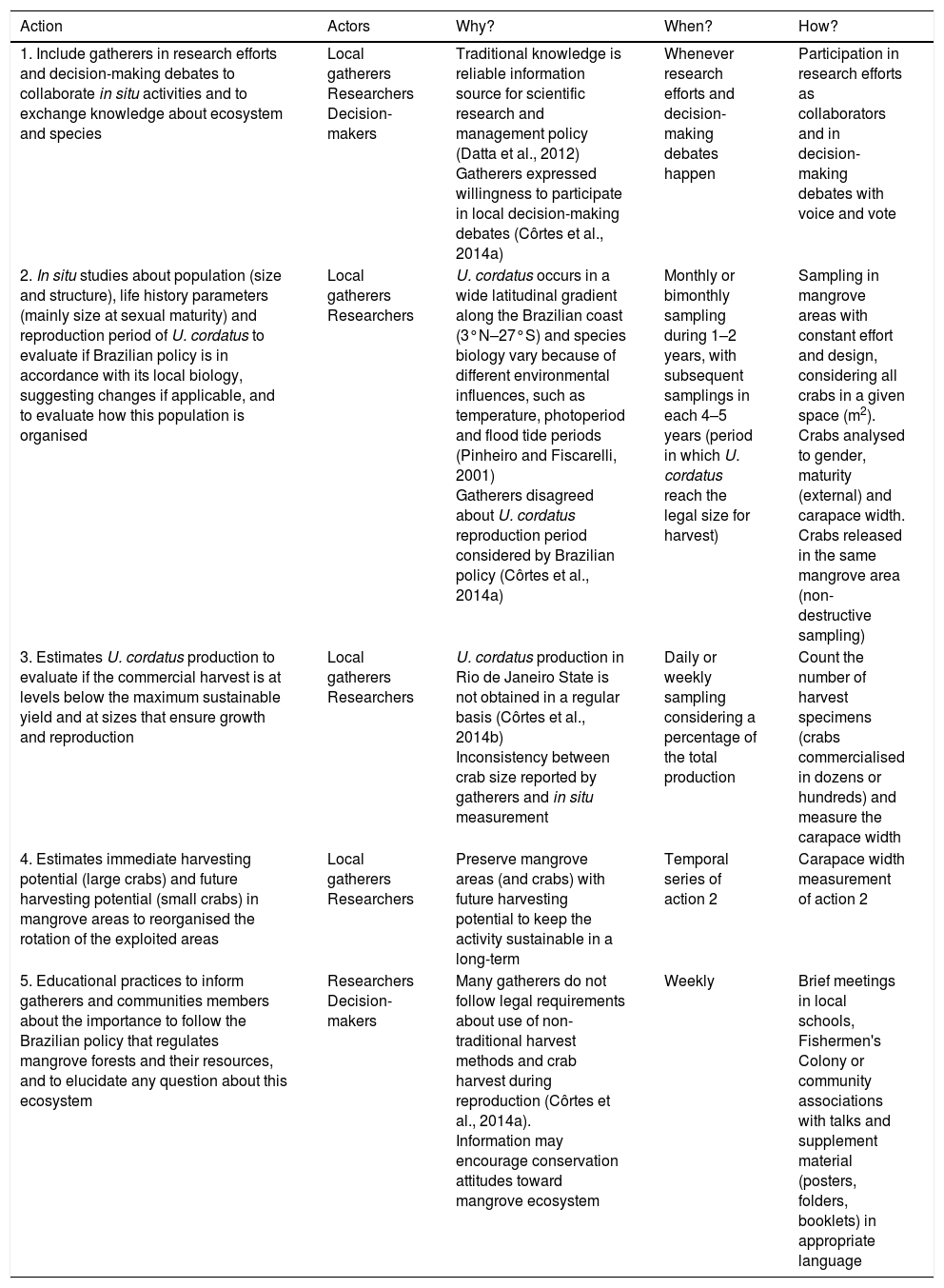

Community-based conservation proposals for the U. cordatus harvest system in this mangrove forest are listed in Table 2. The proposals aim to improve results in the future for both local productivity and ecosystem-resource maintenance and include collaboration to mitigate conflicts, especially between local gatherers and decision-makers. All mangrove areas along the Brazilian coast are Permanent Preservation Areas, where traditional activities, such as the crab harvest, are allowed under specific policies (Federal Law 12.651/2012, available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2012/lei/l12651.htm).

Community-based conservation proposals to the Ucides cordatus harvest system in the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary, south-eastern Brazil.

| Action | Actors | Why? | When? | How? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Include gatherers in research efforts and decision-making debates to collaborate in situ activities and to exchange knowledge about ecosystem and species | Local gatherers Researchers Decision-makers | Traditional knowledge is reliable information source for scientific research and management policy (Datta et al., 2012) Gatherers expressed willingness to participate in local decision-making debates (Côrtes et al., 2014a) | Whenever research efforts and decision-making debates happen | Participation in research efforts as collaborators and in decision-making debates with voice and vote |

| 2. In situ studies about population (size and structure), life history parameters (mainly size at sexual maturity) and reproduction period of U. cordatus to evaluate if Brazilian policy is in accordance with its local biology, suggesting changes if applicable, and to evaluate how this population is organised | Local gatherers Researchers | U. cordatus occurs in a wide latitudinal gradient along the Brazilian coast (3°N–27°S) and species biology vary because of different environmental influences, such as temperature, photoperiod and flood tide periods (Pinheiro and Fiscarelli, 2001) Gatherers disagreed about U. cordatus reproduction period considered by Brazilian policy (Côrtes et al., 2014a) | Monthly or bimonthly sampling during 1–2 years, with subsequent samplings in each 4–5 years (period in which U. cordatus reach the legal size for harvest) | Sampling in mangrove areas with constant effort and design, considering all crabs in a given space (m2). Crabs analysed to gender, maturity (external) and carapace width. Crabs released in the same mangrove area (non-destructive sampling) |

| 3. Estimates U. cordatus production to evaluate if the commercial harvest is at levels below the maximum sustainable yield and at sizes that ensure growth and reproduction | Local gatherers Researchers | U. cordatus production in Rio de Janeiro State is not obtained in a regular basis (Côrtes et al., 2014b) Inconsistency between crab size reported by gatherers and in situ measurement | Daily or weekly sampling considering a percentage of the total production | Count the number of harvest specimens (crabs commercialised in dozens or hundreds) and measure the carapace width |

| 4. Estimates immediate harvesting potential (large crabs) and future harvesting potential (small crabs) in mangrove areas to reorganised the rotation of the exploited areas | Local gatherers Researchers | Preserve mangrove areas (and crabs) with future harvesting potential to keep the activity sustainable in a long-term | Temporal series of action 2 | Carapace width measurement of action 2 |

| 5. Educational practices to inform gatherers and communities members about the importance to follow the Brazilian policy that regulates mangrove forests and their resources, and to elucidate any question about this ecosystem | Researchers Decision-makers | Many gatherers do not follow legal requirements about use of non-traditional harvest methods and crab harvest during reproduction (Côrtes et al., 2014a). Information may encourage conservation attitudes toward mangrove ecosystem | Weekly | Brief meetings in local schools, Fishermen's Colony or community associations with talks and supplement material (posters, folders, booklets) in appropriate language |

For management strategies to be successful, it is necessary to understand the social context of the local communities and include them in decision-making. Such inclusion is important because local actors who depend on extractive activities exploit environmental resources in response to the socioeconomic pressure in which they live, recognising and supporting management strategies only when they feel part of the decision-making process (Carr and Heyman, 2016). Therefore, the public policies that allow the inclusion of gatherers in management strategies may contribute to minimising the overexploitation of U. cordatus in the study site.

The communities of Atafona and Gargaú differ with respect to the importance of the crab harvest for the local economy. In Atafona, the low number of gatherers indicates a declining activity, while in Gargaú the population has a stronger economic dependence on crab harvest (Côrtes et al., 2014a). Currently, the total number of gatherers that harvest U. cordatus for commercial purposes is approximately eight times greater in Gargaú than in Atafona. Atafona is located closer to the ‘Logistics and Industrial Complex of Porto do Açu’ (CLIPA), which offers other income options for the local residents. In addition to the CLIPA, there was an increase in commercial establishments and residences, offering better work conditions for them (Côrtes et al., 2014a). Moreover, fishermen descendants from Atafona are not interesting in became fishermen (Zappes et al., 2016).

The harvest pressure on the species has decreased, considering that the total number of gatherers (and consequently the catch per unit effort) has also decreased: at least 96 gatherers before 2012, 66 in 2012 and 56 in 2016. Hence, one would expect an increase in the crab's size over time. However, the decrease of catch effort is not the only factor related to the crab's size. The loss of the original mangrove area along the years could negatively affected the crab's size and its abundance in this mangrove forest, but previous data are not available to verify this assumption.

The continuity of this crab harvest for commercial purposes between 2002 and 2016 was probably possible because of decreased harvest pressure, and it does not necessarily indicate the effectiveness of traditional management in sustaining the resource. Thus, the crab harvest system in this mangrove forest may be more fragile than expected by the gatherers themselves and may not be viable in the long term. In this sense, the socioeconomic situation of the gatherers from Gargaú community deserves concern because of their strong dependence on this activity.

The local U. cordatus stock may not be readily replenished because of its life history parameters such as slow growth rate, size and age at sexual maturity and longevity. In south-eastern Brazil, the age at sexual maturity was estimated to be approximately 3 years, while the age at minimum size for harvest in Brazilian mangroves (60mm) was 4–5 years. The maximum predicted size ranges from 80 to 90mm, and the longevity has been estimated at approximately 9–11 years (Pinheiro et al., 2005; Costa et al., 2014). The harvesting of crabs near the minimum legal size constrains their reproductive success. The reproductive period occurs once per year followed by one or more spawning events (Castilho-Westphal et al., 2013).

In general, gatherers from both communities (Atafona and Gargaú) are able to describe biological, ecological and behavioural aspects of the crab U. cordatus in this mangrove forest (Côrtes et al., 2014a). However, the gatherers’ LEK regarding the population status of this crab in the sampling site is inaccurate. They believe that the traditional management practices with rotation of the exploited mangrove areas are sufficient for the sustainability of the U. cordatus population (Côrtes et al., 2014a). In contrast, the results showed that the continuity of the crab harvest probably reflects the decreased harvest pressure rather than the local management practices, as discussed previously. This study does not intend to identify possible errors in LEK but, rather, to recognise the aspects of such knowledge could complement the scientific knowledge for the maintenance of the U. cordatus population at sustainable levels for long-term exploitation. The exchange of information between scientific and traditional knowledge can be complex because of differences in the language used by local actors and researchers, which makes it difficult to understand each other (Zappes et al., 2013). Therefore, a cross-cultural relationship (local actors and researchers) is important for mutual understanding to achieve positive results regarding resource management practices (Thomas, 1993; Pena et al., 2017).

The local gatherers reported that the commercialised crabs have carapace widths of between 80 and 90mm (Côrtes et al., 2014a). Our results contradict the ability of local gatherers to estimate the crabs’ size for commercial purposes because the mean carapace width measured in situ (present study) was 35–50% smaller than the size reported by the gatherers (60–63mm vs. 80–90mm). It is not possible to conclude whether the gatherers do not know the real size of the crabs selected for commercialisation or whether they are afraid to report it since most of them know the legal requirement for the minimum carapace size for U. cordatus harvest in Brazil (Côrtes et al., 2014a).

Thus, to what extent are traditional management practices by themselves leading to the sustainability of the mangrove ecosystem and, consequently, of the exploited resources such as U. cordatus? Successful natural resource management practices based on traditional knowledge are largely reported in the literature (e.g., Berkes et al., 2000; Moller et al., 2004; Pagdee et al., 2006; Dreiss et al., 2017). However, there is no consensus on the efficacy of such practices because in some cases is difficult to harmonise political interests, socioeconomic development, biodiversity protection and sustainable resource utilisation (Kellert et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2012). A similar scenario is found throughout mangrove areas where traditional management practices are performed but conflicts also exist (Datta et al., 2012; Abdullah et al., 2014; Roy, 2016). In the mangrove forest of the Paraíba do Sul River estuary, traditional practices are not sufficient to ensure sustainable resource utilisation; moreover, the legal requirements for U. cordatus harvest are not fully followed by the local gatherers, who also report not being invited to participate in the decision-making process (Côrtes et al., 2014a). The proximity between these stakeholders is important to facilitate the exchange of information and experience, making the community-based conservation proposals feasible (Dale and Armitage, 2011).

When traditional management practices and fisheries management policies fail to maintain sustainable natural resource exploitation in the long term, integrative actions among communities, researchers and decision-makers may be an alternative to reach best results in the near future. In this sense, the community-based conservation proposals presented here may apply in any similar U. cordatus harvest system.

Long-term and regular monitoring should be establishing to evaluate biological aspects of the target species, U. cordatus, including population size and dynamics, as well as its productivity in harvests. Researchers should provide scientific information to both local gatherers and decision-makers but also integrate the community members in the research, exchanging knowledge using appropriate language. Educational practices and the inclusion of local gatherers in this process are essential to the success of the integrative actions. Finally, Brazilian decision-makers should be more sensitive to the specific characteristics of a given region, encouraging the establishment of regional policies for the use and exploitation of natural resources instead of a single policy to cover the extensive coast, which is more than 8000km long.

FundingThis work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (Grant Nos. 301.405/2013-1 and 400.053/2016-0) and the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – FAPERJ (Grant Nos. E-26/201.161/2014 and E-26/203.202/2016).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We are indebted to Silvana Ribeiro Gomes for helping with the crab sampling during 2015–16 and to Sergio Carvalho Moreira for doing the map.