The Atlantic goliath grouper, Epinephelus itajara, is a large-sized coastal fish that has been heavily overfished, mainly through spearfishing. In order to assess historical catches of the species, we interviewed spearfishers along three generations (young, middle-aged and old) in the traditional fishing village of Arraial do Cabo, southeastern Brazil. We identified a systematic and significant decline in the weight of the largest goliath grouper caught and in the number of individuals caught on the best day's catch through spearfisher generations. Today, the species is functionally extinct in the region and individuals are rarely sighted. Challenges to the conservation of goliath grouper populations throughout the Brazilian coast include the banishment of poaching as well as the support to alternative income sources through non-extractive uses, such as diving tourism.

Among marine fishes, groupers are the most important artisanal fishing resource worldwide (Heemstra and Randall, 1993). However, twenty grouper species (12%) are currently listed under extinction risk categories and other 22 (13%) are Near Threatened with extinction worldwide according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature – IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Sadovy de Mitcheson et al., 2013). In addition to the threats deriving from heavy exploitation, groupers (Epinephelinae) have biological attributes that contribute to render its populations vulnerable to the effects of fishing such as long life span, slow growth, late maturation, strong site fidelity and the formation of seasonal spawning aggregations (Craig et al., 2011). As a consequence, grouper populations easily collapse when heavily fished, taking a long time to rebound (Heppell et al., 2005).

The Atlantic goliath grouper, Epinephelus itajara, (Litchtenstein, 1822) is the largest grouper species of the Atlantic Ocean, reaching over 2m in length and 400kg in weight (Bullock et al., 1992). The species has been suffering sharp population declines across its entire range due to overfishing and habitat loss (Craig et al., 2009). Today, the goliath grouper is globally classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN (Craig, 2011). In Brazil, the decrease in catches and lack of reliable population data led managers to establish a precautionary fishing ban in 2002. Also, in 2014 the species was listed as Critically Endangered by the Brazilian Red List of threatened species.

Spearfishing is recognised as the main cause of the collapse of the goliath grouper (Sadovy and Eklund, 1999; Gerhardinger et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the effects of spearfishing on reef fishes across longer timeframes, such as decadal periods, are poorly known for Brazilian reefs (but see Bender et al., 2014). Here, we use fishers’ local ecological knowledge – LEK to investigate trends in historical spearfishing catches of goliath grouper populations in Arraial do Cabo, a fishing village in southeastern Brazil. Specifically, our aims were to assess changes in (i) the number of individuals caught over the years and (ii) the weight of individuals caught over the years. The knowledge of resource users has been widely applied to obtain historical data of marine species and populations not registred by the most conventional approaches (e.g. fisheries statistics; McClenachan et al., 2015). Despite the potential biases that may exist in individuals’ memories related to LEK (Papworth et al., 2009), comparisons with biological surveys have shown that when data collection (e.g. interviews, questionnaires, etc.) is well-designed, fishers’ LEK constitute a reliable source of data (Thurstan et al., 2015).

Material and methodsStudy areaArraial do Cabo (22°57′57″S 42°01′40″W) is a traditional fishing village with approximately 1000 active fishers in which aproximatelly 55 are spearfishers. Fisheries are generally multispecific and apply a variety of fishing gears, such as hook and line, gillnet, beach seine and spearfishing, with beach seine being the most traditional practice. The main fishing targets are the bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix, mullets (Mugilidae), jack and trevallies (Carangidae), tunas (Scombridae) and groupers (Epinephelidae). Parrotfishes (Scarinae) became a target in the early 1990s, when the collapse of large predators commenced, and these fishes are mainly captured through spearfishing (Bender et al., 2014). Since 1997, a coastal community-based marine protected area (MPA) was implemented, named Arraial do Cabo Marine Extractive Reserve – ACMER, where fishing rights are granted exclusively to local fishers.

Data collectionSpearfishers were interviewed through semi-structured questionnaires, based on questions used by Saenz-Arroyo et al. (2005). Specifically, we asked three questions: (1) Fishers’ age; (2) the weight of the largest goliath grouper ever caught and the year in which that catch was made; (3) the largest number of individuals caught in a single day and the year of such large catch. Prior to each interview, we clearly explained the objectives of our research, highlighting that the interviewee, as well as the data informed, would remain anonymous. This avoids the potential bias that could arise due to the mistrust of fishers in the use of the data and knowledge by researchers (Thurstan et al., 2015).

Data analysisRespondents were categorized into three groups with ages ranging through three generations: young (15–30 years), middle-aged (31–54 years) and old (≥55 years). A polynomial regression was fitted to verify the relationship among weight of the largest goliath grouper ever caught and greater days’ catch along the years. To compare the largest individual ever caught and greater days’ catch according to spearfishers’ generation, we used the nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) since the response distribution was non-normal and data was nonparametric. A post-hoc test was conducted using Dunn's test – package dunn.test (Dinno, 2017). Analyses were performed using the software R (R Core Team, 2016) at a significance level of p<0.05.

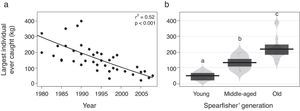

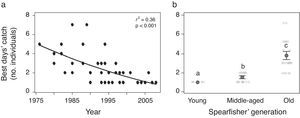

ResultsWe interviewed 42 spearfishers between August 2007 and August 2008 across three different generations: young (n=10), middle-aged (n=15) and old (n=17), corresponding to ∼75% of active spearfishers in Arraial do Cabo during the time of the survey. All spearfishers reported catches of goliath grouper individuals in the past (see Fig. 1). Overall, the average weight of the largest individual ever caught was 169±15.8kg (±SE). The smaller catch reported was an individual of 20kg caught in 2005, and the largest weighed 400kg, captured back in 1979. We identified a significant decline in the size of largest individual caught throughout the years (Polynomial regression r2=0.52, p<0.001; Fig. 2A) and across spearfishers’ generations (Kruskal–Wallis x2=28.72, p<0.001, Fig. 2B). Best days’ catch revealed a marked decline along the years (r2=0.36, p<0.001; Fig. 3A) and across spearfishers’ generations (x2=29.1, p<0.002; Fig. 3B).

Largest goliath grouper individuals caught according to (A) years and (B) spearfishers’ generation in Arraial do Cabo, southeastern Brazil. Generations are defined as: young (15–30 years; n=10), middle-aged (31–54 years; n=15) and old (≥55 years; n=17). In (B) points are the raw data, black line represents the average, bean is the inference interval. Different letters above pirateplots indicate significant differences (Dunn's test, p<0.05).

By assessing spearfishers knowledge, we verified a marked decline in both the abundance and the weight of goliath grouper individuals caught in an interval of 23 years (from 1975 to 2008) in Arraial do Cabo. Historically the species was caught mainly through spearfishing in the region. Behavioral characteristics, such as inhabiting shallow waters, large size, territoriality, docile behavior (Giglio et al., 2014b) make the species susceptible to spearfishing. These characteristics allied to vulnerable life history traits has led many goliath grouper populations close to local extinction even at low fishing pressures (Sadovy and Eklund, 1999). In Brazil, surveys using fishers’ knowledge showed marked declines in goliath grouper abundance, caused mainly by overfishing (Gerhardinger et al., 2006; Ferreira et al., 2014; Bender et al., 2013; Giglio et al., 2015a; Zapelini et al., in press). Despite the fishing ban established since 2002, poaching is still widely reported along the coast (Giglio et al., 2014b, 2016; Freitas et al., 2015) and there are no signs of population recovery. A challenge to the conservation of goliath grouper populations throughout the Brazilian coast is to ban poaching while encouraging alterantive income sources through non-extractive use of the species.

In ACMER, even smaller-sized grouper species have been depleted, such as the dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus, the black grouper, Mycteroperca bonaci, the gag, M. microlepis and the comb grouper, M. acutirostris (Bender et al., 2014). The goliath grouper adds to this list and despite being under a fishing moratorium, the rare individuals found are rapidly poached by spearfishers. In fact, fish species have been continuously replaced as they become depleted and economically unviable to exploit, characterizing a “fishing down the food web” scenario (Pauly et al., 1998). Spearfishers have adjusted their perceptions regarding natural resources to a more degraded environment, suggesting the occurrence of the shifting baseline syndrome among this resource users (Pauly, 1995). Despite the existence of specific fishing regulations in the ACMER, enforcement is poor, making it difficult for managers and stakeholders to establish a sustainable use of resources. An important information to be stressed to local stakeholders is that spearfishing is a highly effective and selective fishing method. The fishes captured include many K strategists, those that attain large sizes, live long, mature later and present sex reversal (sequential hermaphroditism) (Morris et al., 2000; Craig et al., 2011). The combination of gear and specific life history attributes is disastrous for many reef fish species in the family Epinephelidae, with plenty of examples of stocks collapsed around the world (Sadovy de Mitcheson et al., 2013), many associated with species that form spawning aggregations like the goliath grouper. The recent collapse of the endemic Brazilian blue parrotfish, Scarus trispinosus, in Arraial do Cabo is the most recent example of spearfishing effects (Bender et al., 2014). Parrotfishes are caught in the region only through spearfishing, and these fishes became a target to spearfishers only in the beginning of the 1980s. Clearly, reducing fishing effort in the ACMER is essential for fish stocks to recover, but most importantly, recreational spearfishing is no longer sustanaible for many species in the region, and must be controlled.

On the other hand, at more effectively enforced Brazilian no-take MPAs, goliath grouper individuals have been exploited for diving tourism, such as in the Fernando de Noronha National Marine Park – FNNMP and in the Abrolhos National Marine Park (Giglio et al., 2014a). As the species present high site fidelity, these individuals have been sighted by thousand of scuba diving visitors. Large-sized groupers are among the preferred animals to be sighted during dives (Rudd and Tupper, 2002). The occurrence of this docile, large-sized and emblematic fish adds an important attraction to these dive sites. While a large goliath grouper caught can render one or two hundred dollars to poachers, this income can be increased to tens of thousands dollars along several years through dive tourism.

Arraial do Cabo is a highly visited sun and beach destination, and encompasses one of the most visited dive sites of the Brazilian coast, attracting thousands of divers every year (Giglio et al., 2017). Today, nautical tourism is the main income source of the ACMER community, and speafishing is no longer the main income source for the most of active practicioners. Goliath grouper can contribute to improve the local economy by providing an important attraction to diving tourism. Divers may be willing to pay more for goliath grouper encounters (Shideler and Pierce, 2016). As an example, in Brazil other species of large-sized fishes have contributed to increase the revenue of diving destinations, such as sharks in FNNMP (Garla et al., 2015) and the seasonal occurrence of manta rays in the Laje de Santos State Marine Park (Luiz et al., 2009).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank G. Machado for conducting the interviews. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the scholarship offered to VJ Giglio and MG Bender, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the scholarship offered to C Zapelini. CNPq and FAPERJ for continuing support to CEL Ferreira.