Increased human pressure on the planet's resources has lead to extensive loss and degradation of natural habitats increasing overall species’ extinction risk. This has led to the consensus that protected areas are an essential strategy for maintaining biodiversity and the ecological services it provides (Chape et al., 2005; Gaston et al., 2008; Pimm et al., 2014). During the twentieth century, protected areas were created under several different categories of protection in almost all countries around the world (Phillips, 2004). Currently, the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) acknowledges the existence of more than 160,000 protected areas worldwide, covering more than 13% of the Earth's land surface (WDPA, 2012). Brazil holds an outstanding position with fourth largest network of protected areas in the world (Gurgel et al., 2009), encompassing 12.4% of the national land area (WDPA, 2012).

Protecting nature in wilderness regions is already recognized as an important way to preserve biodiversity. However, as a consequence of global urbanization, the value of nature within or surrounding cities is increasing and becoming a viable alternative to preserve and promote biodiversity in urban areas (Araújo, 2003; Alvey, 2006; Kowarik, 2011). Green spaces in urban areas can also provide ecosystem services that benefit cities, such as, climate regulation (Bowler et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2011), water balance (Bolund and Hunhammar, 1999; Gómez-Baggethun and Barton, 2013), carbon storage (Timilsina et al., 2014), and air filtration of pollutants (Escobedo and Nowak, 2009; Escobedo et al., 2010). As well as these ecological benefits, the presence of nature in cities can enrich human lives, such as having a sense of freedom, unity with nature and happiness, and also creating beauty, silence, tranquility, better physical health and social interaction and integration (Chiesura, 2004; Kabisch et al., 2015).

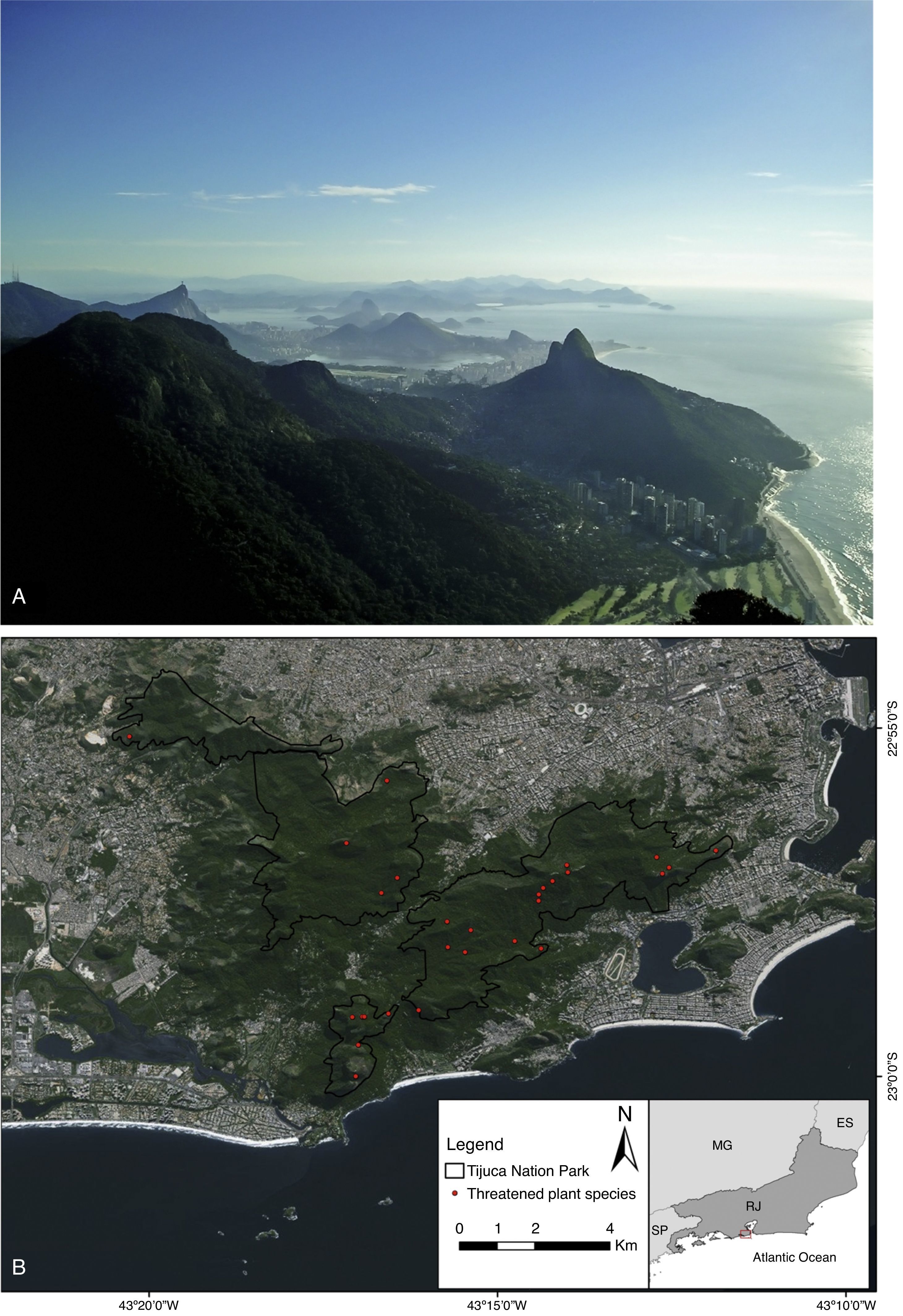

Beyond the importance of these benefits, urban green areas inside or around cities can also preserve threatened species (Kühn et al., 2004; Alvey, 2006; Wang et al., 2007). This is true especially for the largest urban forest in the world, the Tijuca National Park, in Brazil (Mittermeier et al., 2004). The Tijuca Forest was intensely devastated mainly because of sugarcane farms in the seventeenth century and coffee farms in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As a direct cause of such degradation, there was a major crisis in water supply in the city of Rio de Janeiro (Fragelli et al., 2013). In 1861, given the lack of water in the city, the emperor Dom Pedro II demanded the reforestation of degraded areas and, together with the natural regeneration, many areas were recovered (ICMBio, 2014a). This forest became formally a protected area in 1961 and is entirely surrounded by the city of Rio de Janeiro, the second most populous city in Brazil. The park has 3953ha, covering 3.5% of the area in Rio de Janeiro (ICMBio, 2014b).

The Tijuca National Park has great national and international visibility, given that it holds some of the main attractions and tourist destinations in the city and in the country. The monument of Christ the Redeemer located in the Corcovado mountain is one of the seven wonders of the modern world according to the United Nations. The viewpoint “Vista Chinesa”, and the mountains “Pedra da Gávea”, and “Pedra Bonita” are icons of Rio de Janeiro and are also located in this national park. As a consequence, the Tijuca National Park receives about 2 million visitors per year (ICMBio, 2014c) and provides economic benefits for the city (Fragelli et al., 2013). Further, the park was one of the main drivers for the recognition of the city of Rio de Janeiro as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - UNESCO, in the cultural landscape category.

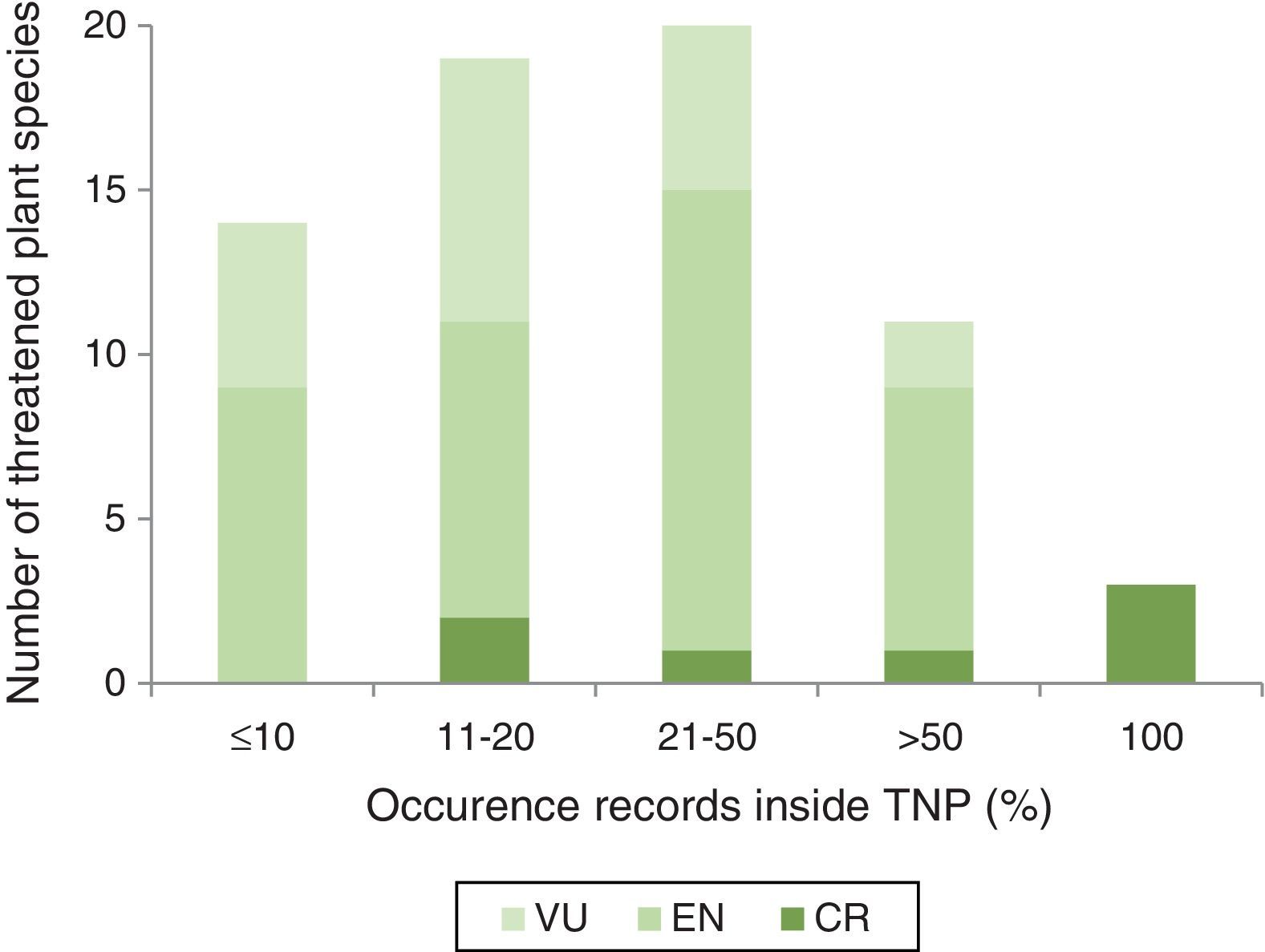

The Tijuca National Park is home of 67 threatened plant species (two of them endemics) that occur in Brazil (Fig. 1), representing 16% of all threatened species in the state of Rio de Janeiro (Martinelli and Moraes, 2013). From these 67 species, seven are classified as Critically Endangered (CR), 40 are Endangered (EN), and 20 are Vulnerable (VU) (Martinelli and Moraes, 2013). These figures could be even higher, as only 20% of the Flora of the state of Rio de Janeiro's have been evaluated so far. Considering all threatened plant species found in the state of Rio de Janeiro, the Tijuca National Park protects 11 species that do not occur in any other protected area, and covers more than 50% of known occurrence records for another 11 species. Fig. 2 shows the number of species protected and their percentage of records found within the park.

In the state of Rio de Janeiro there are 57 protected areas with known occurrence of threatened plant species. Among these protected areas, five are National Parks protecting 44% (188 species) of threatened plant species of in Rio de Janeiro, which harbors 425 species. The Tijuca National Park is the one that holds the highest number of threatened plant species (67 species) in Rio de Janeiro, although it is the smallest National Park in Brazil (MMA, 2014). The Itatiaia National Park, the first National Park created in Brazil, has the second highest number of known threatened plant species in Rio de Janeiro (60 species), although it is more than three times larger than the Tijuca National Park. Though these results could be related to biased sampling efforts given that the Tijuca National Park allows for a quick access for botanists and researchers in general, other national parks in Rio de Janeiro also show a significant level of species records, but without showing that of species protection. In any case, even in face of differential sampling efforts, the park has a substantial contribution for the conservation of threatened plant species in Brazil.

Here we highlight the importance of the Tijuca National Park for the conservation of threatened plant species and the biodiversity in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Moreover, the park is an excellent opportunity to establish or reinforce people-nature relationship that will ultimately raise people's awareness on the importance of biodiversity. As in other urban forests, the Tijuca National Park faces threats, such as the presence of invasive species, impacts of recreational activities, infrastructure impact (roads cutting the park), illegal urban occupation, and internal fragmentation of remaining vegetation by networks of trails. To preserve this urban forest and its threatened Flora species it is important to study the ecological impacts of these threats and ensure the application of research-based management in the Tijuca National Park.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.