Iberá Nature Reserve in the province of Corrientes, Argentina has suffered one of the worst defaunation processes in the country. After acquiring lands within the Reserve, The Conservation Land Trust started the Iberá Rewilding Program in 2007, with the aim of reintroducing all animal species that had been extirpated locally in historic times. Along with its ecological value, this program intended to improve local economies by positioning Iberá as an ecotourism destination. So far, two self-sustaining populations of two species (giant anteater and pampas deer) and five initial population nuclei of four species (giant anteater, pampas deer, tapir, peccary and green-winged macaw) have been established, as well as an ongoing jaguar breeding program. Major obstacles faced during the rewilding process included communication challenges (communicating the program results openly and clearly); bureaucratic challenges (overcoming initial resistance from authorities, academia, and other stakeholders by producing high quality recovery plans and communicating consistently) and species-specific challenges (recognizing each species’ requirements and learning from individual animals’ responses). This experience demonstrates that rewilding projects require abundant suitable habitat, long-term financial and organizational commitment, a solid interdisciplinary team and a high level of flexibility in order to adapt in a changing context. One of the first programs of this kind in the Americas, the Iberá Rewilding Program is being adopted by government authorities, private conservationists and the general public in Argentina, as a model for proactive conservation.

Over the last few decades, the reintroduction of species with primary conservation purposes has been increasingly used as a conservation approach to reverse species extinction (IUCN, 2013). Also, rewilding initiatives involving the reintroduction of species to restore an ecosystem functioning (Seddon et al., 2014) are staring to be carried in Europe (Navarro and Pereira, 2015), North America (Foreman, 2004), Africa (Varty and Buchanan, 1999; Hofmeyr et al., 2003). Species reintroductions have also been reported within South America, with some examples in Argentina (Juliá, 2002; Tavarone, 2004; Jacome and Astore, 2016), in what still represents a fledging conservation field in the region. One of the most remarkable attempts to carry out the rewilding of a large ecosystem by the reintroduction of several species is the Iberá Rewilding Program in North East Argentina.

The Iberá region experienced one of the worst defaunation processes in Northern Argentina during the XXth century (Parera, 2004; Giraudo et al., 2006). Iberá was considered in the past as an untamed territory with abundant wildlife, where only hunters or explorers would venture to enter. A long history of European colonization, combined with cattle ranching activity based on the frequent use of fires and dogs, along with subsistence and intensive commercial hunting for fulfilling the European market of animal products (fur, leather, feathers, etc.) during the second half of the past century, were primary contributors to this defaunation process (Parera, 2004; Di Blanco, 2014). Species such as giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), collared peccaries (Peccary tajacu), tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), green-winged macaws (Ara chloroptera), jaguars (Panthera onca), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), which inhabited the area became extinct in the whole province, while two of the three pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) populations in the province also disappeared (Parera, 2004; Giraudo et al., 2006) Other species such as the maned wolf (Crisozyion brachiurus), marsh deer (Blastoceros dichotomus) and cougar (Puma concolor) became very scarce in the region (Fabri et al., 2003). In 1983, with an increasing national interest in conservation, Iberá was declared a 13,000km2 nature reserve (Iberá Nature Reserve – INR). Later, in 2009, a portion of its public lands were declared a Provincial Park. These protection measures enabled the slow recovery of the region's wildlife, including what are presently abundant populations of caimans (Caiman latirostris and C. yacare), marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus), brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira) and rheas (Rhea americana).

Since 1999, an international non-profit conservation organization, The Conservation Land Trust (CLT, http://www.theconservationlandtrust.org/), funded by philanthropists Douglas and Kristine Tompkins, bought 1500km2 of private lands inside the INR. These lands were then managed for conservation and ecological restoration purposes in order to be turned into a 1400km2 national park, adjacent to the 5500km2 Iberá Provincial Park. In 2016, the presidents of CLT and Argentina signed a protocol to establish a national park which, combined with the existing provincial park, would form Iberá Park (http://parqueibera.corrientes.gob.ar/); the largest protected area of its kind in Argentina (7000km2).

In addition to the parks creation, a group of Argentinean scientists recommended the reintroduction of several extirpated species that would not be capable to recolonize the region by themselves (Parera, 2004). Following these recommendations, CLT developed the Iberá Rewilding Program (IRP), aimed at re-establishing sustainable populations of all locally extirpated fauna. The IRP follows the definition of rewilding described by Seddon et al. (2014) as “species reintroduction to restore an ecosystem functioning”. Hence, our reintroductions were mainly aimed to advance ecological restoration instead of individual species endangered recovery. This program is part of the larger Iberá Project, which also aims to create Iberá Park and promote local development and pride through ecotourism (http://www.proyectoibera.org/en/especiesamenazadas.htm). The IRP started in 2007 and nowadays includes the reintroduction of giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus), collared peccaries (Peccary tajacu), tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), and green-winged macaws (Ara chloroptera). We also started an onsite breeding program aimed at restoring the role of jaguars (Panthera onca) as top-predators to the area. Even if cougar (Puma concolor) presence in Iberá has been registered during recent years in camera traps there have not been images of cubs or different individuals that indicate the presence of a resident population of this predator. Besides its ecological potential, rewilding has also been used to promote the Iberá region as a wildlife tourism destination that would encourage local development.

As far as we are aware, the IRP represents the largest initiative aimed to restore several animal species in a single ecosystem within the Neotropics. This fact, along with the conservation opportunity that Iberá Park represents in terms of size and protection level, converts the restoration of Iberá into a unique case in a continent where the creation and management of protected areas is more common than the proactive management of wildlife species for recovery. The past ten years of wildlife reintroduction in Iberá have generated a great amount of practical experience, not only in terms of species management, but also in terms of organizational, political and administrative issues. The objective of this manuscript is to describe the Iberá Rewilding program, its methods, approaches, results and lessons learnt. In this way, we expect to motivate other projects aimed at restoring species or ecosystems in the region, thereby generating an expansive movement toward using rewilding as a tool for proactive wildlife restoration.

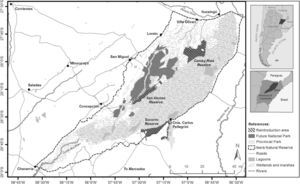

The Iberá ReserveThe INR (13,000km2) is located in the province of Corrientes, in Northeastern Argentina (Fig. 1). Local climate is subtropical with mean temperatures varying from 15°C to 28°C in the coldest and warmest months respectively, and an annual rainfall of between 1.500 and 1.800mm (Neiff and Poi de Neiff, 2006). Iberá is composed of various environments including marshes, lagoons, small rivers, temporarily flooded grasslands, savannas, and forests. INR was created in 1983 (Provincial Law 3773/83) and combines public and private lands. In 2009, 5530km2 of public lands were declared as a Provincial Park, and were thereby strictly protected by provincial authorities. Among private lands, most of which are dedicated to cattle ranching and pine production, The Conservation Land Trust (CLT) holds 1500km2, currently protected as six private reserves, which will be donated to the nation to create a national park, adjacent to the existing provincial park (CLT, 2017).

Among CLT's reserves, three have been chosen for wildlife reintroductions: Socorro, San Alonso and Cambyretá (Fig. 1). These lands were operated as cattle ranches until they were bought by CLT, at which point cattle was excluded and a natural restoration process began. Socorro is located at the Southeastern edge of INR, and consists of 124km2 of grasslands, gallery forest and wooded savannas, bordered by wetlands to the North, the town of Pellegrini to the East and private lands to the South and West. San Alonso is a 114km2 island surrounded by the Paraná lagoon and the Carambola stream to the West, with uninhabited wetlands around its remaining limits. It represents the most elevated land within its surroundings, which contributes to its high vegetation diversity, composed of temporarily flooded and well-drained grasslands, forests patches and palm trees. Cambyretá is a 225km2 piece of land located in the Northern portion of INR. Its landscape is composed of grasslands, forests patches and marshes. Cambyretá was the first section of the CLT reserves to be donated to create Iberá National Park and, since 2016, it is being managed by the National Parks Administration.

Villages and small towns surround INR, the most populated of which are the city of Ituzaingó (20,000 in by 2010), and the villages of San Miguel (4700 in by 2010), Concepción (4000 in by 2010), Loreto (2000 in by 2010) and Colonia Carlos Pellegrini (890 by 2010) (INDEC, 2010). There are also some small hamlets adjacent to or immersed in the Iberá reserve, where a few families (i.e. less than 1000 people in total) live off of cattle and subsistence farming.

Steps in the reintroduction processPlanning, feasibility assessments and permitsWe initially listed the species that had been extirpated from Iberá and for which evidence of their past presence in the region was available (Fabri et al., 2003; Parera, 2004; Giraudo et al., 2006). In 2005, we carried out a participative workshop with local experts and the director of INR to establish a first list of species that should be reintroduced based on their conservation status and habitat suitability. We designed and wrote recovery plans for all reintroduced species; giant anteater (Jiménez Pérez, 2006), pampas deer (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2009a), collared peccary (Jiménez Pérez and Altrichter, 2010), tapir (Di Martino et al., 2015), green-winged macaw (Berkunsky and Di Giacomo, 2015) and jaguar (The Conservation Land Trust, 2013). For some species (anteater and jaguar) recovery plans were drafted as a result of participatory workshops, and for each reintroduction project we consulted national and international experts (see Annex 1), including the chairs of IUCN Species Specialist Groups (Anteater, Sloth and Armadillo; Deer; Peccary and Tapir). We also visited institutions carrying out similar projects in different countries (México, Brazil, India, South Africa, etc.) to learn from similar experiences.

We carried out formal assessments of the knowledge and attitudes of local people toward giant anteaters (Delgado et al., 2008) and jaguars (Caruso and Jiménez Pérez, 2013; Zamboni, 2015). In the case of pampas deer, tapirs, peccaries, giant anteaters and green-winged macaw, we invited experts on the species to visit the potential release areas in order to carry out a qualitative habitat suitability assessment based on their expert opinion. For the jaguars, a formal quantitative habitat suitability assessment was carried out by an external jaguar expert (De Angelo, 2011). Prior to the release of the first anteaters, a Population Viability Assessment (PVA) was performed using hypothetical data (bibliographic sources and expert opinion) to project population trends under different reintroduction and management scenarios (Jiménez Pérez, 2006). The results helped us to choose the best management options during the release process and identify the main factors that could affect population persistence in the future. We presented final recovery plans to the relevant provincial and national wildlife authorities for their approval. The approval process for each animal usually took between six months and two years of meetings, negotiations and paper-work. Sometimes, even with the approved plans, animal movements required special permits.

In general, the wildlife authority in Argentina belongs to the provinces. Due to the provincial governments’ lack of previous experience in cooperating on wildlife translocation there was initial difficulty in getting permits to move animals from other provinces to Corrientes. In general, we could mostly get authorization to move animals that were in captivity. The only case in which we could get authorization to capture and translocate wild animals from another province was with two anteaters, and this permit was quickly revoked. The only exception to that rule was pampas deer, which were captured and translocated from the wild within the province of Corrientes (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2016a).

Source of animalsAs explained above, with exception of pampas deer, all population founders came from captivity. In the case of giant anteaters, we mostly worked with orphan animals whose mothers had been killed in the wild and who had been later raised in households or put on sale in illegal markets (Jiménez Pérez, 2013). We obtained peccaries, tapirs, green-winged macaws and jaguars from zoos or animal rescue centers in Argentina (with the exception of a jaguar that was donated by a wildlife rescue center in Paraguay). With all the necessary granted permits, we moved these animals from their original locations to the province of Corrientes using specially adapted trailers and boxes.

For pampas deer, we carried out translocations from a wild population located along the Aguapey river basin in the East of Iberá (one of the four remaining populations in the country), distributed within private cattle ranches and pine plantations. This population of around 1000 individuals (Zamboni et al., 2015a) is found in private properties that lie outside of public reserves. Habitat modifications due to forestry and illegal hunting are constant threats to the population (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2007). Deer were immobilized by darts and transported on planes or helicopter to their pre-release pens.

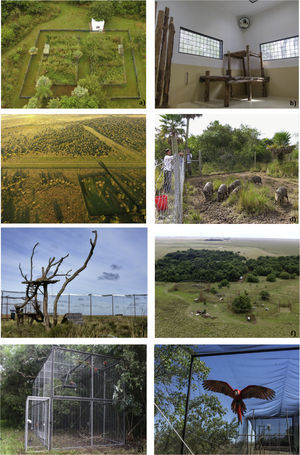

Quarantine phase and hand-rearingBecause there were no previous examples of reintroductions for most of these species, we needed to design and develop new protocols, including the hand-rearing of anteater cubs (Miranda et al., 2006), radio-tagging (Di Blanco et al., 2013), feeding supplementation (Miranda et al., 2007), regular recaptures, soft-releases (Di Blanco et al., 2013; Jiménez Pérez et al., 2009b), and other techniques. For each species, with the exception of pampas deer, animals went through a quarantine process, because all individuals came from captivity. Two quarantine facilities were designed and built to receive animals intended for release where they spent between one and a half to three months. One of these facilities meets international quarantine standards, which enabled us to bring animals from neighboring countries. During the quarantine phase, we performed health checks and genetic analysis, tested radio-collars and performed any needed medical treatments. Orphaned giant anteater cubs were raised in small pens at the giant anteater rescue center (Fig. 2) until they reached the size at which they could be released.

Part of the Rewilding project infrastructure. (a) Giant anteater rescue center with six pens. (b) Jaguar quarantine facility. (c) Pampas deer pre-release pen (below) and sanctuary (above). (d) Peccary, anteater and tapir pre-release enclosure. (e) One of the breeders facility in the CECY. (f) View of the enclosures for jaguar breeders and larger enclosures for mothers and offspring at the CECY. (g) Green-winged macaw's shelter cage. (h) Green-winged macaw's flight tunnel.

After the quarantine process was complete, animals went through an acclimatization phase in their release sites within the CLT reserves (Fig. 2). We reintroduced the first giant anteater, peccary and tapir populations and the second pampas deer population in the Socorro reserve (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2016b; Jiménez Pérez et al., 2016a; Hurtado, 2017; Di Martino et al., 2015). The first pampas deer and the second giant anteater populations, as well as the Jaguar Experimental Breeding Center (Centro Experimental de Cría de Yaguaretés or CECY, see below), were established in the San Alonso reserve (Jiménez Pérez et al., 2016a,b, Solís et al., 2014). Green-winged macaws were released in the Cambyretá reserve due to its abundance of forest patches (Berkunsky and Di Giacomo, 2015).

Soft-releases were typically carried out in 1-ha pens (Fig. 2). These were usually the same for all the species, with exception of green-winged macaws and jaguars, for which we built specially designed aviaries for the former and an onsite breeding center for the later. The green-winged macaw aviary includes a 25m long corridor, where animals receive special training during their pre-release period (Fig. 2). An animal trainer specialist helped us to train macaws in order to improve their anti-predator response and flight capacity for short and long distances. Preconditioning exercises included the use of a trained cat and a falcon, which simulated attacks to an embalmed macaw near the birds that would be released while playing macaws warning calls. Flight exercises included the use of automatic food dispensers located on both extremes of the flight cage, which delivered food combined with a bip sound. When animals heard the sound they flew from one extreme to the other, repeating the flight several times for a total flight length of 2km.

While in their pre-release enclosures, we fed animals from different species with specially designed food, depending on their needs. Macaws, tapirs and peccaries were given local native fruits. Animals were periodically checked for their overall health status, and to confirm that radio-tags were well-fitted and not causing any significant injuries. In the case of injuries caused by radio-collars or harnesses, the animals were anesthetized by our veterinarians to perform necessary adjustments or medical treatments.

In the case of the pampas deer population reintroduced at Socorro we built a second 30ha pen with electrified wires that could hold animals for months or years (Fig. 2). This pen can allows for animals to breed during one or two reproductive seasons in a controlled space before releasing them into the wild, in order to reduce dispersal and its associated mortality.

Jaguar Breeding CenterSince we do not have authorization to release wild jaguars in INR yet, we planned, negotiated and got approval for an onsite jaguar breeding program. The Experimental Jaguar Breeding Center (Centro Experimental de Cría de Yaguaretés o CECY) was specially designed to breed captive jaguars so that they would produce offspring that would be capable of living in the wild, hunting by themselves and showing no affiliation or dependency on humans. The center's overall design came as result of several meetings with jaguar and large cat reintroduction specialists and visits to other felid reintroduction programs. The facility consists of four interconnected enclosures of 1200m2 for breeders, two 1.5ha enclosures for mothers and their offspring and a large 30ha enclosure where juvenile jaguars can hone their hunting abilities (Solís et al., 2014, Fig. 2). All enclosures are 5 meters high, with 12 lines of electric wire, and 1m of over-hang. Enclosures include grasslands, forest patches and environmental enrichment spaces (dead trees, platforms, ladders, pools, etc.). Enclosures for cubs have automatic food delivery systems, which enable staff to deliver food without the animals establishing an association with humans (Solís et al., 2014). Jaguars chosen as breeders belong to the genetic group identified by Eizirik et al. (2001) that includes all Argentinean jaguars. Detailed management methods and protocols for animals included in the onsite breeding program are available at Solís et al. (2014).

Reintroduced population monitoring and demographic evaluationPrior to their release, all animals are fitted with VHF transmitters. Pampas deer were tagged with Telonics 400 and 500 transmitters. In the case of males we placed extensible collars as advised for male cervids. Tapirs were fitted with collars carrying Telonics 500 transmitters, while peccaries carried collars with Telonics 400 and 500 transmitters, plus ATS M2220B collars. In the case of macaws they were fitted with Holohil AI-2C collars. All collars and harnesses for mammals included activity and death sensors. For anteaters, we designed and improved several harness models considering their particular physiognomy all of them carrying Telonics M400/350 VHF transmitters. Details on the giant anteater harnesses and transmitters, including its functioning and improvement are described at Di Blanco et al. (2013). Once the pre-release period was complete, we opened the enclosure to let the animals exit by themselves. We carried out post-release monitoring of all individuals, consisting in periodical sightings with the help of a hand-held antenna, recordings of their GPS localization, and overall status checks (e.g. wounds, body condition, presence of cubs, etc.; Di Blanco, 2014; Zamboni et al., 2015b). In the case of anteaters, we usually removed harnesses after two years of living in the wild for males or after having two batches of offspring for females. This was carried out to avoid regular captures to treat wounds caused by the harnesses (Di Blanco et al., 2013, 2015).

During the first few months after release, some animals received supplemental food. This consisted of fruits and vegetables for tapirs and peccaries along with specially designed dry food (also used for pampas deer), vegetables, fruits and seeds for macaws and a special preparation for anteaters, consisting of liquefied apples or banana, cat feed and milk, placed in a plastic bottle inside a cage fixed to the ground. For pampas deer, we periodically carried out scheduled grassland burns aimed at producing re-growth and increasing the quality of available grasses.

For all species, new-born individuals, once independent from their mothers, could not be readily monitored since they had no radio-tags. For anteaters, we installed trap cameras (Reconyx, Inc; Rapidfire HC500, Holmen, Wisconsin, USA, set for taking pictures) in sites frequently used by the anteaters (forest edges, trails, etc.) and baited them with food to assess their status and detect new individuals (Di Blanco et al., 2015). Free-born anteaters were marked with distinctive ear marks, enabling us to identify individuals through photographs (Zamboni et al., 2014).

Demographic assessmentWith the first population of giant anteaters, we performed a post-release population viability analysis (PVA) in order to compare with the one carried out as part of the recovery plan (Zamboni, 2016). We used Vortex 10 (Lacy and Pollak, 2014) to simulate the reintroduced population's dynamics over 100 years under different scenarios of demographic parameter values. We used telemetry and camera trap monitoring data from our ten years of monitoring the reintroduced population to estimate the model's parameters. We used the location of the reintroduced individuals, obtained from telemetry monitoring, to estimate the area's carrying capacity for the PVA model, thereby generating a habitat suitability map for the reserve and a potential expansion area (Zamboni, 2016).

We estimated female annual reproductive rates and annual mortality rates for released animals and cubs born in the wild. For anteater, pampas deer and peccary populations, we estimated the reproductive rate as a mean of the proportion of females that gave birth each year over the total number of reproductive females (Lacy, 2000). We excluded females during their first year of reintroduction, to avoid a post-release effect due to translocation stress affecting their reproductive fitness.

We estimated mortality as a mean of number of deaths/total individuals for each year. For the giant anteater population established in Socorro, we estimated mortality rate as a mean of mortality rate estimated separately for cubs, juveniles (under two years old) and adults for each year. Collared peccary annual mortality rate was estimated as a mean of mortality (no. of deaths/total individuals) for each year, estimated separately for each released group. Only groups that had spent at least one year released were considered. For species that had not already spent one year released (tapirs and macaws) mortality was estimated as number of deaths/total individuals. In absence of long-term demographic data that allowed for the development of PVAs, we considered a reintroduced population nucleus as self-sustaining (i.e. it would increase without need of further release) when the number of births surpassed the number of deaths for at least three consecutive years.

Communication and program evaluationWe used different approaches to communicate program results: technical reports for wildlife authorities at the provincial and national level, and conservation organizations; scientific papers and talks at scientific conferences for academia; and online newsletters, social media, explanatory videos, posters and brochures for the media and general public. We also published a high-format book explaining the giant anteater reintroduction project (Jiménez Pérez, 2013), and have interacted extensively with journalists and documentary film-makers to assist them in communicating about the program. In absence of a formal evaluation on our communication efforts, we have detected a clear increase in public awareness and popularity about the IRP at local, provincial, national and international levels, expressed in person to person conversations, social networks and general media (magazines, newspapers and TV news).

We used monitoring results as a basis for our evaluation and learning process. Data coming from the animals and the human environment surrounding them were discussed at regular evaluation meetings with our team and external experts. These meetings were vital in clarifying roles within the team, and solving possible interpersonal conflicts that could arise. External experts visited the projects often and provided input on ways to improve. In the case of the giant anteater, we invited an experienced veterinarian (Wanderley de Moraes) to carry out a formal external review of our quarantine facilities. In the case of the jaguar project we organized four planning and evaluation meetings in which team members, national and international experts, and wildlife authorities discussed, reviewed and improved our working protocols (see advisors on Annex 1).

Current status of the rewilding programThe IRP has already established seven reintroduced populations of five species (giant anteater, pampas deer, peccary, tapir and green-winged macaw; Table 1), distributed across three of our reserves (Socorro, San Alonso and Cambyretá) within the larger INR. The first two established populations (giant anteaters in Socorro and pampas deer in San Alonso) already fulfill our criteria to be considered self-sustaining (see above and Table 1). Additionally, the PVA carried out for the first giant anteater population showed a 99% probability of persistence in 100 years (Zamboni, 2016). The second population of giant anteaters already shows better survival and reproductive data than the first, probably due to continuous improvement to our pre-release and post-release management protocols. Several of the reintroduced population nuclei still need to be augmented (see Table 1) and new ones will be established in the near future in these or other sections of the future Iberá National Park. The first group of jaguar cubs is expected by 2018, with the potential to release them in Iberá Park around 2019.

Reintroduced species status in different CLT reserves (sites); population size estimated from available post-release monitoring data and demographic parameters; no. of total animals reintroduced; no. of animals confirmed to have been born in the wild; no. of animals confirmed to have died in the wild (released+born onsite); number of nuclei established; no. of self-sustaining populations (i.e. no. of births>no. of deaths for at least three consecutive years); reproductive rate estimated from released females and Mortality rate estimated from released animals and cubs born in the wild.

| Species | Site | Estimated population size | Animals | Established nuclei | Self -sustaining populations | Reproductive rate (%) | Mortality rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reintroduced (starting year) | Born in the wild | Died in the wild | (Mean±SD) | (Mean±SD) | |||||

| Giant anteater | Socorro (2007) | ∼80 | 32 | >36 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 67±20 | 12.34±1.52 |

| San Alonso (2013) | ∼27 | 23 | >10 | 5 | 53±3.50 | 5.33±9 | |||

| Pampas deer | Socorro (2015) | 13 | 14 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 85 | 21±9.28 |

| San Alonso (2009) | >100 | 23 | >60 | 14 | 86±14.77 | 9.18±6.79 | |||

| Peccary | Socorro (2015) | ∼22 | 29 | 11 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 80 | 41±28.83 |

| Tapir | Socorro (2017) | 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Green winged macaw | Cambyretá (2015) | 8 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| Jaguar | San Alonso (2015) | 4 breeders | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | – | – |

In a few cases (i.e. less than 20% of the released animals), anteater, pampas deer, peccary, tapir and macaw individuals have dispersed to neighboring areas. Neighbors have reported seeing individuals within their properties and contacted us. When possible, we relocate these individuals back into their releases areas to improve their chances of breeding with other congeners and their survival against possible threats, like harassment by dogs or hunting. We consider these relocations necessary during the first stages of the reintroduction process when numbers are still low. It is likely that dispersion increases along with an increase in population sizes, in which case relocations are be carried out only when we detect a clear risk for a specific individual or a concrete conflict with people. Nonetheless, all the release sites hold high quality habitats compared to neighboring lands, reducing the probability of animal dispersal out of protected areas, or serving as havens for reestablished populations. Some incipient evidences of an ecological role by the reintroduced species have been registered, such as the growth of tree seedlings from tapir's feces, indicating the role of this species on seed dispersal. Nonetheless, more time and studies will be necessary to measure the ecological effect of the rewilding process.

Lessons learned after 10 years of reintroductionsWe recognize two main organizational strengths that have helped us to achieve our rewilding results in Iberá: the availability of large areas of high-quality and well-protected habitat for released animals (some of which were owned and managed by us), and the existence of long-term funding that allowed us to work for more than 10 years. These advantages are not always available to reintroduction projects, which usually face difficulties in habitat and funding availability. Despite these significant advantages, we had to overcome several challenges along the way to achieving our goals:

Communication challengesConvincing stakeholders (e.g. wildlife authorities, academia, NGOs, local communities, mass media, etc.) that reintroductions made sense and were possible in Iberá was not easy. The initial positions of the public toward the IRP were primarily either ambivalent or negative, in many cases because they were related to feelings of distrust toward the idea of a foreign organization buying private lands to create a national park. In contrast with other continents (e.g. North America) conservation philanthropy is seen as an anomaly in Latin America. Comments of doubts or disapproval toward the idea of species reintroductions were usually heard within local villages or in meetings with academics, conservationists and environmental authorities. As there were no clear precedents in the collective imagination, several conservationists tended to oppose proactive management and many non-conservationists did not see any clear benefit. However, once the program started to show progress and we were able to communicate the ecological (i.e. reintroduction as a tool for ecological restoration) and social (i.e. reintroduced animals as eco-tourism attractions) benefits to a wide array of groups, this attitude changed in favor of widespread support, as was represented in person to person conversations, social networks and the media. Throughout this process, we learned about the importance of proactive and honest communication that shows concrete results, and shares both the good and the bad (i.e. loss or deaths of individuals) news. To achieve this, we used a wide array of communication channels including; an updated website, newsletters, presentations in neighboring villages, scientific meetings, technical reports and scientific articles, brochures, posters, books, documentaries, stickers, a Facebook page, educational activities with children, and more. We also invested significant human resources toward inviting journalists to the area in order to show them the different reintroduction and on-site breeding activities. Additionally, we found that relating the rewilding concept to local development is a useful way to gain support from politicians, top-level decision-makers and neighbors. We discovered that, in order to make the public feel as part of the project, we needed to acknowledge their role and impact on the program's results. In this way, people felt like active participants in species recovery, adopting and supporting the project's goals.

Bureaucratic challengesA significant part of our time was invested in negotiating for animal donations from public and private donors and getting the permits for their transport and release. Achieving this was not an easy task. Having good experts on our side and well-drafted recovery plans helped us to receive the requested permits from wildlife authorities, while having a good public image was critical for convincing animal donors. Dissipating this initial reticence also required constant communication with authorities, local and international experts, and a great amount of patience, in order to decide whether it was better to insist on moving forward or to wait and identify when there was a clear intention from specific civil servants to block the process. In this regard, it was important to communicate about the projects at all the levels of public office; from technicians to high-level decision makers (e.g. ministers).

Funding challengesThe IRP has been supported from the beginning with CLT's own funding, not only for the reintroduction activities but also for park creation, conservation outreach and local development. Nonetheless the complexity of actions related with reintroductions during these years increased the overall budget. This required looking for external funding, either from individuals or institutions. The success of our first projects on giant anteater and pampas deer reintroduction was important to gain credibility and reliance on our foundation, which gained support from external donors, either through direct funding or supplies (construction material, vehicles, animal feeding, technical equipment, etc.) and services (technical advice, translations, legal support, etc.) We are now facing the need of keep on financing our projects with external funding. In this regard, communicating our project in an efficient way and to a variety of publics increases the chances to find national and international partner organizations.

Species-specific challengesSince there was no similar wildlife restoration projects in Latin America from which to learn and draw upon, we found that we had to experiment with many unknown variables. In order to organize our working strategy we began by asking ourselves some general questions for each species, such as: What do we know and what do we need to know? What should our general working approach be? How should we organize ourselves for each project? What are the potential areas of conflict?

At our first participatory meeting we decided to start with what considered as the easiest and least controversial species (i.e. giant anteater) since it did not have experts who “owned it” or stirred high positive or negative passionate feelings from the public. From there we moved on to what we considered, at that time, to be the most urgent (i.e. pampas deer), which had some conflictive precedents of failed management actions and had a higher conservation profile in order to establish a reputation for credibility and efficiency in the eyes of the local community, and our conservation peers. We deliberately did not publically announce our goal to reintroduce jaguars until we had established such a reputation, because we thought it would overshadow and thwart the other species recovery projects.

Each animal – not just each species – is different, and many individuals tend to behave in unexpected ways that contradict our working theories. A good way to improve our methods was to let the animals guide us through their behavior. To this end, intensive monitoring of all released animals was essential for improving our working methods. Every animal released in the wild has to have its survival, general health and reproduction monitored. It is common to have higher losses at the beginning of each project, but progress is incremental and things improve when you persist, monitor, evaluate, adapt and learn from each loss or gain. This also helps to establish a well-trained team and identify key areas of improvement.

We have learned from each species along the way. For instance, we came to learn that we should avoid releasing individuals during or near winter. It is important to let animals get used to their new environment in favorable, warmer weather, rather than in low temperatures and less hospitable conditions. In the case of anteaters, releasing individuals in pairs proved to increase their anchorage to the release site and limited initial long-distance travel. With peccaries, it proved to be useful for the animals to be released in cohesive and smaller groups in order to avoid aggressive behavior among individuals and protect against predators.

Food supplementation during the first few months after animals are released and during the first winter spent in the wild improves chances of survival. Adding native fruits to their diet helps animals to get used to their new food source and to find it in the wild. It is also advisable to avoid that the animals see us leaving them this extra food. In addition to direct food supplementation, carrying out scheduled grassland burning was proven to be positive for pampas deer populations as it improved pasture quality. All this practical and contextual learning from actual experience will make any project improve through the years.

Future plansWe are aware that a rewilding program requires long-term commitment in order to accomplish its ultimate goal of reestablishing viable populations and their ecological functions. On this regards, CLT has agreed with the National Park Administration the continuation of the IRP until 2026, even when all our lands are donated to the public. We plan to carry on further reintroductions of the six species we have been working within other CLT reserves. We also started advising and collaborating with private reserves within Corrientes and near provinces which also intend to carry out the reintroduction of extirpated species (giant anteaters, peccaries, tapirs, marsh deer, etc.). Considering we only have obtained the permits for breeding jaguars, we are expecting the first cubs to be born in order to request the authorities an authorization for the release of individuals in Iberá. Provincial and national wildlife authorities have already shown clear signs that are interested on authorizing and promoting these releases. Finally, we intend to start the reintroduction of other species in the region within the next years such as giant otters, bare-faced curassow, and red-legged seriema, among others.

ConclusionsReintroduction of extirpated animals is more an adaptive challenge than a technical task. Adaptive challenges tend to be complex, ambiguous and open-ended. They depend on the values and interests of many stakeholders, and it is not possible to find a single, optimal and objective scientifically-based solution. Thus, succeeding in a rewilding project involves long-term commitment, a solid team and a high level of flexibility to adapt in a changing environment. Real and dynamic contexts and sociopolitical complexity require a new professional approach to program planning. A broad interdisciplinary team requires not only good technical and scientific skills but also needs to manage social, political, economic and communication aspects to provide broader contextual understanding that results in well-grounded and effective decisions. Rigorous planning is necessary in every step of the process, yet one must keep in mind that things can go wrong and plans will likely need to be revised and adapted along the way. The best way to inform such adaptation is through intensive monitoring of all released animals and awareness of the likely reactions of key stakeholders such as public authorities, academia, conservation NGOs and the general public. In this regard, it is crucial to accept mistakes as part of the learning process as long as they are identified quickly and used to improve planning and performance.

In many cases, conservation teams are led almost exclusively by biological and veterinary experts on the relevant species. It is important to identify people with the best practical experience and to learn from them, but also to be cautious of experts with extensive biological and theoretical knowledge who have no previous experience in actual reintroductions. It is important to listen to everybody's opinion but to be ready to displease someone when you try to change the status quo, as proactive management is often met with skepticism, if not hostility in some conservation and academic circles.

Over the years, we have been able to establish a highly motivated team of professionals who share a common vision, are able to put aside personal agendas, cooperate with management authorities, manage interpersonal conflicts in an educated and positive manner, and enjoy working together. Avoiding unproductive conflict has been crucial in furthering our work as we are now able to invest all our energy into achieving results and learning quickly.

Despite technical and adaptive challenges, the Iberá Rewilding Program has been able to achieve significant results in restoring extirpated species, with two well-established populations (giant anteaters and pampas deer) and five other initial population nuclei (giant anteater, pampas deer, tapir, peccary and green-winged macaw), as well as an ongoing and publicly supported jaguar breeding program. We have also been able to convert the public's ambivalent or negative attitudes into widespread support. Nowadays, wildlife authorities in Argentina (National Parks Administration, Ministry of Environment, provincial wildlife authorities, etc.) are beginning to include the reintroduction of extirpated species within their own policies; something that would not have happened several years ago. Even conservation-minded land-owners have started to include reintroductions and translocations within their management plans, reaching out to us for advice and technical support. As result, we believe that rewilding programs could advance the agenda of ecological restoration and improve the general public image of conservationists when they combine good scientific and social foundations, communicate in a proactive and honest way, and relate ecological concerns with society's wider social interests.

We would like to thank authorities from Corrientes province and Argentina for their support and partnership throughout this process. Also the provinces of Santiago del Estero, Salta, and Formosa allowed for transportation of several animals to Corrientes. To the Biological Station of Corrientes and the Aguará Conservation Center where animals go through quarantine and pre-release treatments. We are also thankful for the Iberá Provincial Park and Iberá National Park park-rangers, who have collaborated with the CLT team. Special thanks to all institutions that donated animals to be reintroduced: Horco Molle Experimental Station (Tucumán University), Salta Native Wildlife Station, the zoos of La Plata, Olavarría, Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Bubalcó, Guaycolec Rescue Center, Atinguy Wildlife Reserve (Yacyretá Binational Entity), the Ministry of Ecology (Misiones), Aguará Cuá SA, as well as staff from El Potrero and Don Luis Reserve for their help in the field, and to health professionals from the National University of Corrientes and Córdoba for their help in animal health tests. Funding for this program came mainly from CLT with additional supports from our donors: the Bromley Charitable Trust, Leonardo Di Caprio Foundation, the BBVA Foundation; Barcelona, Chester, Artis, and Parc des Felins zoos, The National Geographic Society, Ferrero, and anonymous donors. Materials and equipment were donated by Techint, Acindar, Primia, Volkswagen Argentina.

This program has been the joint effort of the CLT team at Iberá who have worked really hard to “make the impossible possible”. Among them, we must acknowledge the key role of Sofía Heinonen, Alicia Delgado, Gustavo Solís, Marisi López, Yamil Di Blanco, Pascual Pérez, Emanuel Galetto, Karina Spørring, Jorge Peña, Ana Carolina Rosas, Noelia Volpe, Rafa Abuin, Marian Labourt, Leandro Vazquez, Maite Ríos Noya, Florencia Pucheta, Nicolás Carro, Jorge Verón, Giselda Fernández, Nicolás Medrano, Alejandro Benítez, Adrián Di Giacomo, Malena Srur, Cristian Schneider, Pablo Díaz, Javier Fernández, Berta Antunez, Marianela Masat, David Moreno, Constanza Paisán, Inés Pereda, Noelia Insaurralde, Magalí Longo and many others. Also, the long-term vision and institutional commitment of Douglas and Kristine Tompkins were the foundation of this program. Thanks to Anna Juchau for her revision of the draft of this article. The study area map was developed by Cristian Schneider. Finally, a special thanks to all the volunteers who have collaborated with our projects, and worked selflessly during their stay.