This study shares the experience of the Integrated Conservation Program for the black-faced lion tamarin, Leontopithecus caissara, on measuring its conservation success. We present the program history and evaluate its impact from 2005 until 2014 in the Ariri region, at Cananeia, São Paulo, Brazil. To assess impact we combined an evaluation of the Econegotiation, a strategy that looks for involve various social segments into conservation through participative forums, with the Threat Reduction Assessment. Econegotiations analysis made possible to estimate the reduction of direct threats, which is considered the most difficult step in the application of Threat Reduction Assessment. We identified a 20–30% reduction in threats, expressed by better political coherence and use of natural resources within the region. Our study revealed two factors that influence the success of integrated conservation and development projects: (i) the ability to integrate in the local context and influence it to make biodiversity conservation an interest shared by diverse actors and leaders, and (ii) the weight of our biocentric vision in defining the target condition constrains the calculation of Threat Reduction Assessment. As lessons learned, we highlight vital aspects to consider in conservation and sustainability: (i) initial effort to know the territory's social, cultural, and economic profile; (ii) clarity of direction and focus on the program's mission; (iii) consolidation of partnerships at all levels; and (iv) strategy to discuss, understand, and overcome conflicts, such as Econegotiations in the black-faced lion tamarin program, can act on critical threats and identify approaches and partnerships to reduce them.

Conservation biology brings with it values, principles, and teachings that have influenced and motivated generations of biologists and professionals in the biodiversity conservation arena (Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005; Meffe et al., 2006). Within the various approaches of this multidisciplinary science, integrated conservation and development projects (ICDPs) incorporate participative and continuous approaches, aiming to integrate conservation of biodiversity with the social and economic development of communities that neighbor environmentally relevant areas (Berkes, 2004; Franks and Blomley, 2004; McShane and Wells, 2004). Despite diversification in past decades (Waylen et al., 2010), these approaches derive from the combination of critical points for sustainable development (decreasing poverty and economic imbalance, empowerment and political participation, and training and process institutionalization) and the conservation of biodiversity (creation and management of protected areas, natural resource management, and protection of threatened species and ecosystems) (Robinson and Redford, 2004).

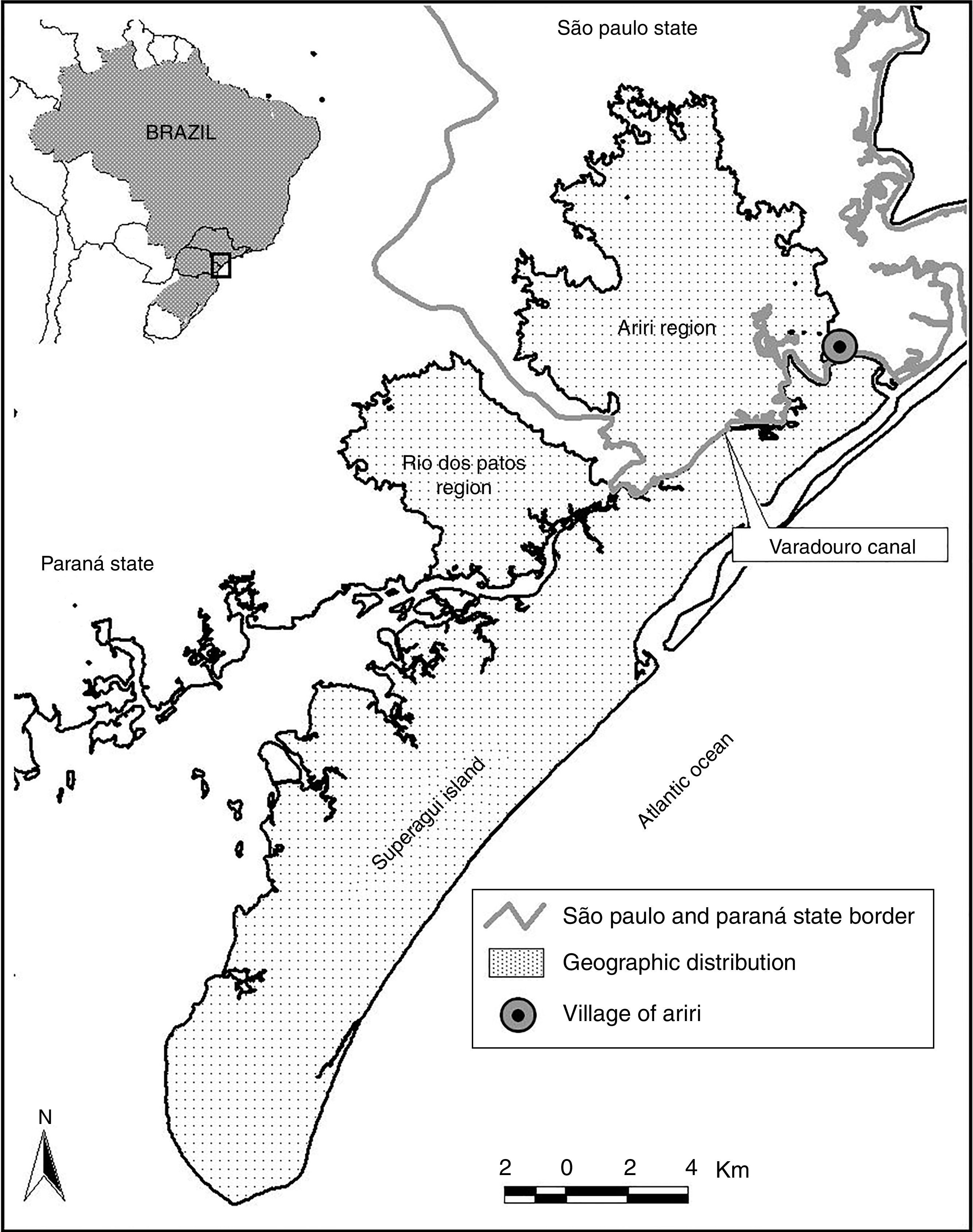

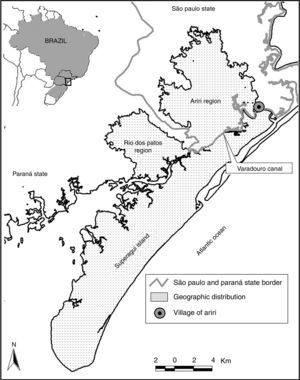

Since its scientific description in 1990 (Lorini and Persson, 1990), the black-faced lion tamarin (Leontopithecus caissara) has been ranked among the critically endangered species (IUCN, 2008). The species conservation status had changed to endangered on last review of the Brazilian official list of threatened species (Ludwig et al., 2014). L. caissara conservation status should also change in IUCN red list of threatened species soon. This change reflects the efforts for its better scientific knowledge and conservation, which have been underway since the beginning of the 1990s. We focus here on decade in between 2005 and 2014, and on the ICDP placed at the extreme southern coast of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, in the Ariri region, at the municipality of Cananeia (Fig. 1). The region is part of the largest remnant of the Atlantic Rainforest in Brazil. Beyond being a hotspot of biodiversity, the Lagamar region is recognized as a Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site. The Lagamar de Cananeia State Park is part of a mosaic of 43 protected areas between the states of São Paulo and Paraná. Ariri village is the largest community of people within the known limits of the continental distribution of L. caissara, containing approximately 80 families.

The challenge we had to integrate biodiversity conservation and local sustainable development at the Ariri region were inspired by the Econegotiation experience in the conservation of the black-lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysopygus) (Padua, 2004; Padua et al., 2006). The Econegotiation is a participative forum, involving various social segments, aimed to stimulate local actors to form alliances and partnerships to address best practices and decrease pressures and threats to the local natural heritage. The two-day workshops, mediated by professionals on conflict resolution, were based on the principle that all participants should express their opinions and ideas, discuss socio-environmental challenges, and identify solutions for the sustainable development of the region. Therefore, the Econegotiations were planned as arenas to discuss and overcome challenges, using the conflicts and different interests to negotiate local strategies and policies. Beyond inhabitants and leaders of the Ariri village, leaders from neighboring communities, organizations, and agencies functioning in the region participated in identifying and discussing strategies. An average of 30 participants attended each workshop in 2009 and 2013.

Throughout one decade, besides contributions to better understand the species ecology, we sought the involvement and participation of diverse actors and social interests related with conservation and sustainable development of the region of work. The positive impact of our intervention is based on the assumption that programs that integrate socio-environmental projects for the conservation of biodiversity can contribute to cultural fixation of the sustainability paradigm (McShane and Wells, 2004; Robinson and Redford, 2004).

Impacts of conservation efforts are traditionally assessed through biological indicators, varying from aspects of one population to ecosystem functions, depending on the level of biodiversity of interest (Noss, 1990). Conservation biology awakened to the need to go beyond this and looked for novel ways to measure impacts. Among the strategies to address this challenge, adaptive management should be highlighted (Salafsky and Margoluis, 2004; Foundations of Success, 2009; Dietz et al., 2010) alongside the development of indicators, including cost–benefit and cost-utility indexes (Cullen et al., 2001; Laycock et al., 2011), indexes based on achievements and goals and result chains (Cullen et al., 2001; Brooks et al., 2006; Kapos et al., 2009; Dietz et al., 2010; Howe and Milner-Gulland, 2012; Margoluis et al., 2013), and the Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA) (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999; Margoluis and Salafsky, 2001; Mugisha and Jacobson, 2004; Anthony, 2008; Matar and Anthony, 2010; Laycock et al., 2011). To contribute to this context, this study aims to: (i) present the Integrated Conservation and Development Program for black-faced lion tamarin (ICDPBFLT) history; (ii) measure its impact combining Econegotiation and Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA); and (iii) share lessons learned.

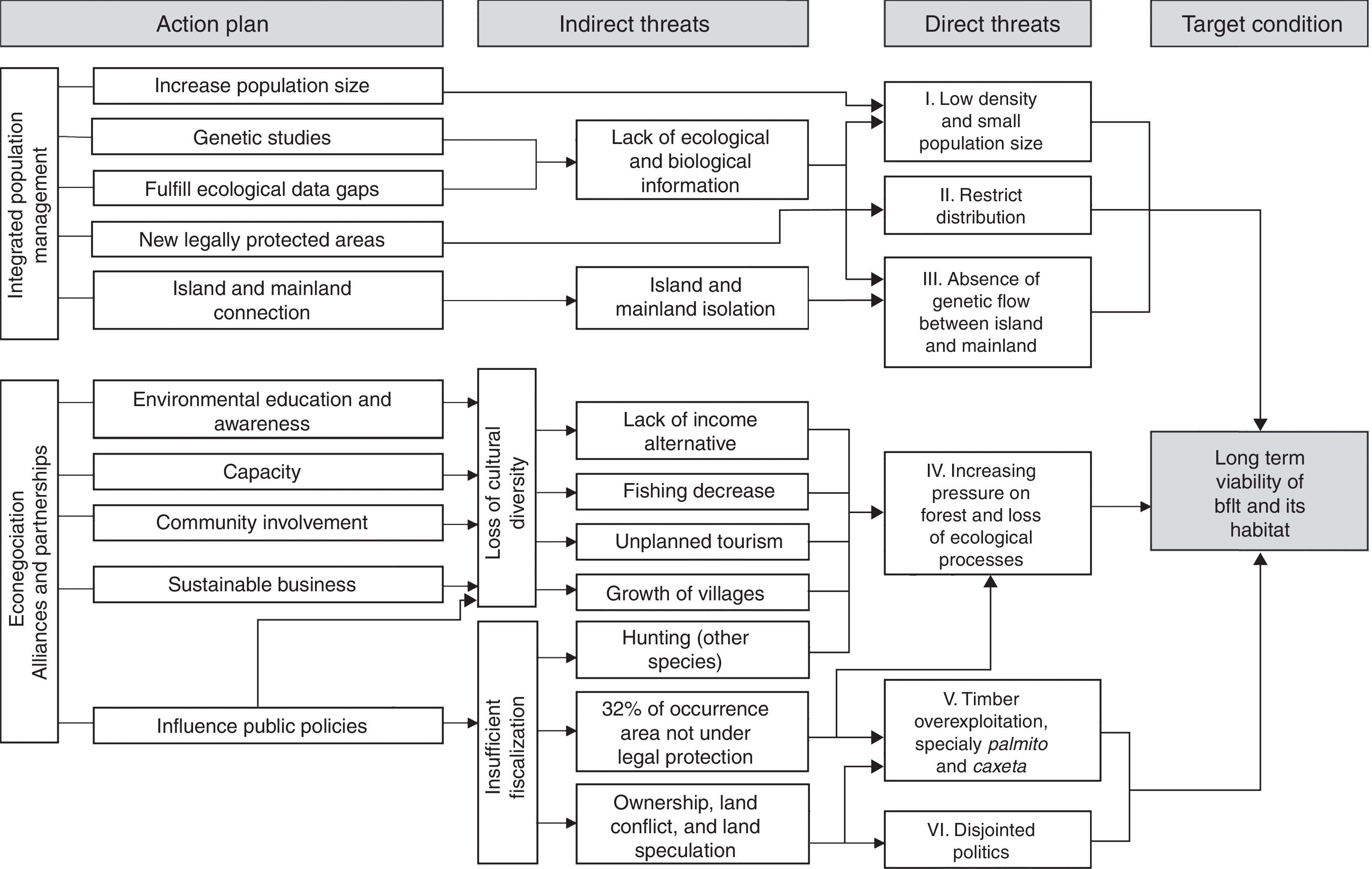

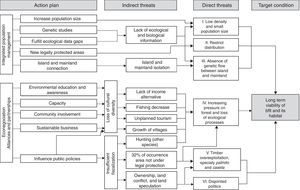

History of the Integrated Conservation and Development Program for black-faced lion tamarinThe 2005 Lion Tamarin Population and Habitat Viability Analysis indicates that the main threats and gaps of ecological knowledge for L. caissara were in its continental distribution area in the state of São Paulo (Holst et al., 2006). Motivated by these needs, in early 2005 we defined three goals: (i) change the species’ critically endangered status; (ii) maintain the long-term quality and quantity of habitat; (iii) make the species a flagship for socio-environmental education, community involvement, and sustainable business to improve human well-being and the conservation of biodiversity. We first organized the logic of an Integrated Conservation Program in a conceptual model (Fig. 2) – a broad image of the work, which helped us strategically plan actions to reach our goals. This systemic approach we used was revised and improved over the years to delineate and implement ICDPs (Salafsky et al., 2002; Salafsky and Margoluis, 2004; Salafsky et al., 2008; Conservation Measures Partnership, 2013; Foundations of Success, 2009; Dietz et al., 2010).

To render viable the action plan we spent an average of one week per month from 2005 to 2014 in the Ariri village. We divided our field time between researching lion tamarins and with activities alongside the communities. The joint approach with local actors – aimed at gaining their involvement and participation in initiatives favoring the conservation of biodiversity – can be divided between after and before the first Econegotiation at April 2009.

Between 2005 and 2007, our aim was to identify the leaders in the region and understand the organization of institutions and agencies, as well as their functions and relationships with our conservation goals. In this initial phase we worked with informal interviews and formal and informal presentations by our team. During this, we always carried albums’ of photos from the studies on the tamarins. We knew that we drew the attention and curiosity from the people, who wanted to understand “why we spent so much time in the forest running after tamarins.” The photos helped us create an informal environment in which to discuss the tamarins and our work.

As a motivational strategy, throughout 2008 we held “coffees with sustainability” – informal events where we presented examples of transformations by other communities in similar conditions. We visited leaders (community, organized civil society, public and private organizations) whom we perceived to be committed, or who had the potential to commit, to local processes for sustainable development integrated with biodiversity conservation. At the beginning of 2009, we invited these leaders to the Econegotiation workshop.

The first day of the Econegotiation in 2009 was marked by tense moments among participants. Many of the attending institutions brought with them a strong negative stigma – repression in the face of the life practices of the local community (as chiefs of conservation units and environmental police) or incompetence in providing public services (as city hall secretaries of development, environment, health and education). The mediators’ expertise was key to harnessing this tension in favor of constructing a general scenario to identify possible points of negotiation and draw strategies to overcome them.

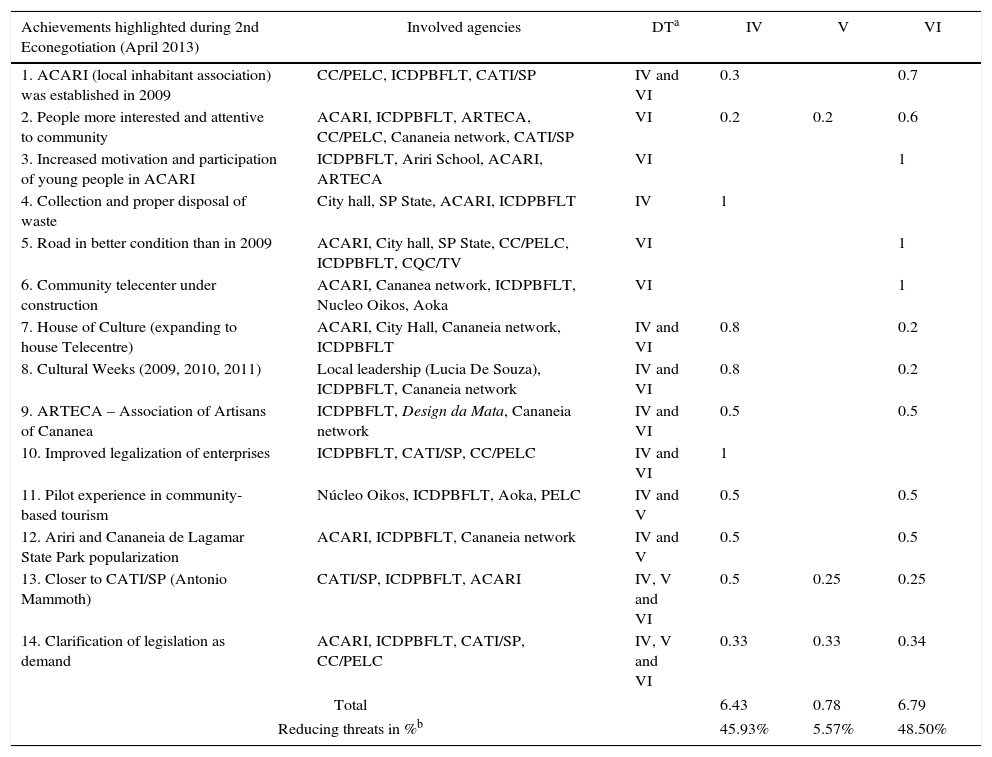

The Econegotiation was the first time that Ariri village receive so many different agencies and authorities to discuss local problems and challenges, and after the workshop we noted that local leaders had awakened from political and social stagnation. Since Econegotiation was incorporated as an umbrella strategy (Fig. 2), from 2009 the program involved diverse approaches (Table 1) – community organization and mobilization (creation of local associations); education and awareness (cultural weeks, leadership training, environmental education, rural legal assistance); and sustainable businesses (artisans improvement and community-based tourism experiences). These approaches overlapped and contributed so that over time, local leaders became more trusting and receptive to our team, ideas, and goals.

Relationship between achievements identified at the second Econegotiation and reduction of direct threats to the long-term viability of black-faced lion tamarin and its habitat in the Ariri region.

| Achievements highlighted during 2nd Econegotiation (April 2013) | Involved agencies | DTa | IV | V | VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ACARI (local inhabitant association) was established in 2009 | CC/PELC, ICDPBFLT, CATI/SP | IV and VI | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| 2. People more interested and attentive to community | ACARI, ICDPBFLT, ARTECA, CC/PELC, Cananeia network, CATI/SP | VI | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 3. Increased motivation and participation of young people in ACARI | ICDPBFLT, Ariri School, ACARI, ARTECA | VI | 1 | ||

| 4. Collection and proper disposal of waste | City hall, SP State, ACARI, ICDPBFLT | IV | 1 | ||

| 5. Road in better condition than in 2009 | ACARI, City hall, SP State, CC/PELC, ICDPBFLT, CQC/TV | VI | 1 | ||

| 6. Community telecenter under construction | ACARI, Cananea network, ICDPBFLT, Nucleo Oikos, Aoka | VI | 1 | ||

| 7. House of Culture (expanding to house Telecentre) | ACARI, City Hall, Cananeia network, ICDPBFLT | IV and VI | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| 8. Cultural Weeks (2009, 2010, 2011) | Local leadership (Lucia De Souza), ICDPBFLT, Cananeia network | IV and VI | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| 9. ARTECA – Association of Artisans of Cananea | ICDPBFLT, Design da Mata, Cananeia network | IV and VI | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| 10. Improved legalization of enterprises | ICDPBFLT, CATI/SP, CC/PELC | IV and VI | 1 | ||

| 11. Pilot experience in community-based tourism | Núcleo Oikos, ICDPBFLT, Aoka, PELC | IV and V | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| 12. Ariri and Cananeia de Lagamar State Park popularization | ACARI, ICDPBFLT, Cananeia network | IV and V | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| 13. Closer to CATI/SP (Antonio Mammoth) | CATI/SP, ICDPBFLT, ACARI | IV, V and VI | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 14. Clarification of legislation as demand | ACARI, ICDPBFLT, CATI/SP, CC/PELC | IV, V and VI | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Total | 6.43 | 0.78 | 6.79 | ||

| Reducing threats in %b | 45.93% | 5.57% | 48.50% | ||

Estimated dividing total each direct threat (IV, V and VI) by 14, the number of achievements listed during 2nd Econegotiation that was directly related with direct threats.

IV, refer to the direct threat “increasing pressure on forest and loss of ecological processes” (Fig. 2) or “biological resource used” (Table 2); V, refer to the direct threat “timber overexploitation, especially palmito and caixeta” (Fig. 2) or “Logging & Wood Harvesting” (Table 2); VI, refer to direct threat “disjointed politics”; CC/PELC, advisory council of Lagamar de Cananea State Park, São Paulo Forest Research Foundation; ICDPBFLT, Integrated Conservation and Development Program for black-faced lion tamarin; CATI/SP, Integral Technical Assistance Coordination of São Paulo state; ACARI, Associação da Comunidade Caiçara e dos Amigos do Ariri, Ariri local inhabitants and association; ARTECA, Association of Artisans of Cananea; Nucleo Oikos, Brazilian support agency that become directly involved in some activities; Aoka, Agency for Sustainable Tourism; Design da Mata, NGO borner from ICDPBFLT and Nucleo Oikos committed to fair trade crafts from the Atlantic Forest and Amazonian communities; Cananea network, Cananeia local NGO; CQC/TV, Brazilian TV Program.

The second Econegotiation took place four years later in April 2013. This second workshop saw the return of many participants, presenting strategic solutions for challenges already identified in 2009, but not resolved. It was planned so that participants could also highlight achievements since the first Econegotiation (Table 1).

Measuring impactEvaluation from Econegotiation and Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA)To make impact evaluation simple and low cost, we integrated an evaluation of Econegotiation with the Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA) (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999; Margoluis and Salafsky, 2001). We assume that ICDPs are complex and transdisciplinary. Therefore, their impact indicators should refer to a socio-environmental intervention model in which the causal chain between efforts undertaken, and changes they hope to achieve, are as explicit as possible. Fig. 2 portrays this chain at late 2004 and early 2005 and defines the summarized target condition for our program, direct and indirect threats, and strategies and approaches to decrease threats and realize the target condition. It is worth noting that three of the direct threats (“low density and small population size”, “restrict distribution” and “absence of genetic flow between island and mainland”) are due to the little knowledge about the species in 2005, and also to our expectation that the advancement of studies in mainland region could expand the small geographical distribution and low density of L. caissara.

Evaluation of EconegotiationTo measure the impact of the Econegotiation, we used its action plan reports and ICDPBFLT conceptual model (Fig. 2). We primarily depended on the report from the second Econegotiation, which highlighted achievements between the two events. In addition to identified advances since the first workshop in 2009, participants of the second Econegotiation also discriminated the agencies and institutions responsible for each achievement (Table 1). This analysis allowed us to verify the impact of Econegotiation in generating partnerships to deal with challenges at region of work. The achievements indicated in Table 1 represent 68% of the actions agreed to at the first Econegotiation.

Achievements pointed were related with decrease on direct threats such as “increasing pressure on forest and loss of ecological processes”, “timber overexploitation, especially palmito and caixeta”, and “disjointed politics”. When the achievement related to more than one threat, we attributed values to each so that the total for each achievement was equal to one. The sum of each threat was divided by 14 (total number of achievements) and multiplied by one hundred (Table 1). This allowed us to estimate the reduction of direct threats listed in 2005, when we considered each threat to be 100% present, as suggested the TRA approach (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999; Margoluis and Salafsky, 2001). This analysis made it possible for us to apply the TRA method and have a more consistent analysis of impact of our conservation program.

For a comparison to other ICDPs strategies, Econegotiation mirrors action n° 7: External Capacity Building (7.1 Institutional & Civil Society Development, 7.2 Alliance & Partnership Development) in the unified taxonomy of conservation actions (Salafsky et al., 2008; Conservation Measures Partnership, 2013).

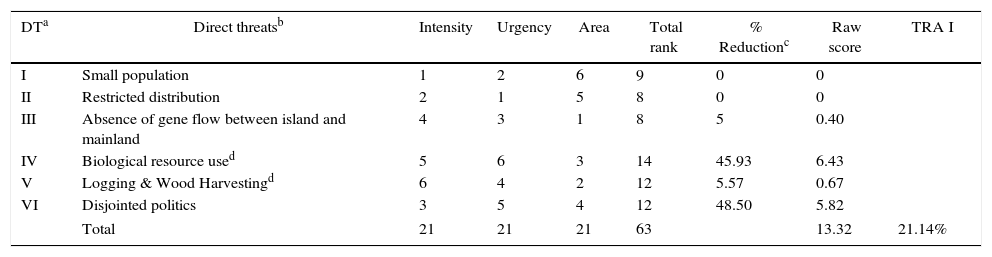

Assessing conservation impact through TRA methodThreat Reduction Assessment involves seven steps, as presented by Salafsky and Margoluis (1999). To apply TRA into ICDPBFT, we follow these steps starting from the scenario outlined at the initial moment (Fig. 2) and used Econegotiation to estimate the reduction of direct threats (Table 1). This step of estimate threat reduction is considered the most important and difficult in the application of TRA (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999). We believe that this has been a good approach for these estimates, since Econegotiation expresses an opinion corroborated by diverse actors participating in the workshop.

Applying TRA steps, we list direct threats as its intensity (impact of the threat), urgency (immediacy of the threat) and area (percentage of the habitat in the site that the threat will affect). The sum of these three factors for each threat creates a ranking that is multiplied by the percentage that each threat has been reduced to determine the raw score (Table 2). To gain perspective on the impact of those threats not reduced by any percentage (“low density and population size” and “restricted distribution”) on achieving our target condition, we present two TRA estimates in Table 2. These final threat reduction indexes were obtained by adding up the raw scores for all threats divided by the sum of the total rank (63 to calculate TRA I and 30 to TRA II at Table 2).

Calculation of Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA) for the Integrated Conservation Program for the black-faced lion tamarin from 2005 to 2014 in the Ariri region. TRA I consider all direct threats and TRA II excludes the analysis of threats not reduced during the study period.

| DTa | Direct threatsb | Intensity | Urgency | Area | Total rank | % Reductionc | Raw score | TRA I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Small population | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| II | Restricted distribution | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| III | Absence of gene flow between island and mainland | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 0.40 | |

| IV | Biological resource used | 5 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 45.93 | 6.43 | |

| V | Logging & Wood Harvestingd | 6 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 5.57 | 0.67 | |

| VI | Disjointed politics | 3 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 48.50 | 5.82 | |

| Total | 21 | 21 | 21 | 63 | 13.32 | 21.14% | ||

| DTa | Direct threatsb | Intensity | Urgency | Extent | Total rank | % Reductionc | Raw score | TRA II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | Absence of gene flow between island and mainland | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0.25 | |

| IV | Biological resource used | 4 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 45.93 | 5.05 | |

| V | Logging & Wood Harvestingd | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 5.57 | 0.39 | |

| VI | Disjointed politics | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 48.50 | 3.40 | |

| Total | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 9.09 | 30.29% | ||

DT, direct threat related in the estimation of the threats reduction by analyzing the Econegotiation (Table 1).

Small population and limited distribution represent direct threats to species viability (100% reduction=BFLT minimum viable population); absence of gene flow between island and mainland threat is given by isolation between these populations (100% reduction=Gene flow reestablished between island and mainland populations); use of biological resources, equivalent to “increase the pressure on the forest and loss of ecological processes”, stems from the limited income opportunities, tourism unplanned, growth of towns and reduction of fishing (100% reduction=no disturbances and impacts from local communities on the forest); timber overexploitation, especially palmito (Euterpe edulis) and caixeta (Tabebuia cassinoides) (100% reduction=timber management); disjointed politics corresponds to isolated leaders and institutions efforts, the local lack of infrastructure and health care efforts, and administration of Conservation Unit Ares on different public spheres (100% reduction=leaders, agencies and institutions acting jointly and in a planned way; basic public services offered).

Adaptation to the taxonomy suggested by the Conservation Measures Partnership and IUCN Species Survival Commission (Salafsky et al., 2008).

The evaluation of Econegotiation was a useful measure of the status of direct threat reduction by our conservation program. This treatment indicated a reduction of 48.50%, 45.93%, and 5.57% respectively for the direct threats of “political disarticulation,” “use of biological resources,” and “logging” (Table 1). Econegotiation was able to involve diverse actors in discussing the problems, challenges, opportunities, and virtues of the territory. The alliances and partnerships established ensured that local leaders applied the strategy, which is fundamental to success.

We believe that the territory was a great test bed for Econegotiation, because the Ariri community had never had the opportunity to establish an open and mediated dialog to level local actors’ views and interests. This was reflected in the greatest impact achieved on the direct threat “disjointed politics”. In fact, our greatest achievement was creating partnerships and dissolving the “black hole” between some institutions and leaders with distinct or similar interests.

The establishment of the Lagamar de Cananeia State Park council after the first Econegotiation in 2009 contributed to the process of discussions and overcoming challenges and conflicts. As in the Econegotiation workshops, this council's meetings served as trade-off arenas for the conservation and development of the region. Our experience demonstrated that participation in these councils, outlined in Brazilian laws, is an important opportunity for social actors, including ICDPs, to influence public policies that genuinely reflect and represent society's interests.

The experience with Econegotiation and its developments have helped us understand that the conservation of biodiversity depends on the social and political empowerment of the actors involved. This process motivates alliances and partnerships that work in concert with our conservation targets. Perhaps this is a subjective measure, and the number of sustainable businesses generated or the increased income could be more concrete and easier parameters to work with. However, for the success of the classic strategy of generating income by ICDPs, local actors must incorporate conservation with their own interests (Salafsky et al., 2001; Kareiva et al., 2012; Soulé, 2013). This is a process that takes, on average, a decade (Berkes, 2004; Franks and Blomley, 2004).

Threat Reduction Assessment (TRA I and TRA II) and the impact of ICDPBFLTThe TRA I index of 21% in Table 2 indicates the impact of ICDPBFLT in nearing its target condition considering all direct threats as they were presented in 2005. The TRA II of 30% reveals that by excluding the analysis of non-reduced direct threats, the impact on our target condition is slightly greater. Therefore, we reduced between 20 and 30% of the threats to the viability of L. caissara and its habitat. This impact is mainly expressed by greater political articulation and the use of natural resources.

Higher TRA values are limited by the context of the L. caissara conservation program, in which, biological characteristics have a strong effect on the conservation of the species. Based on this situation, we demonstrated that the causal relationship toward conservation is not as explicit as in other systemic arrangements that deal with less complex situations (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999, 2004; Salafsky et al., 2008; Foundations of Success, 2009; Dietz et al., 2010). Three of the six direct threats (small population, restricted distribution, and absence of genetic flow) to be reduced would need L. caissara population management (in which case the only possible strategy is translocation, since there is no captive population) or landscape interventions (reconnecting the Varadouro Canal, a piece of engineering that in 1950 isolated Superagui island from the continent). These interventions, if materialized, must be based on a set of ecological information that was not available for the black-faced lion tamarins in 2005. Therefore, the indirect threat that at the time was connected to the direct threats in question was the existence of “Lack of ecological and biological information” (Fig. 2), as pointed by the species action plan (Holst et al., 2006).

A high percentage of these gaps were filled by research undertaken between 2005 and 2014 [behavioral (Moro-Rios, 2009; Ludwig, 2011; Barriento, 2013) and genetic studies (Martins et al., 2011); comparison of use of space between the continental and island population (Nascimento et al., 2011; Ludwig, 2011); habitat selection (Nascimento and Schmidlin, 2011); dispersion standards and new group formation (Nascimento et al., 2014); and long term habitat use for continental groups (Nascimento, unpublished data)], thus reducing much of this indirect threat. However, this reversal does not affect the direct threats of small and isolated populations endemic to lowland forest. In the impact analysis, we consider only a small reduction (5%) in the direct threat “isolated populations”, since based on our studies a federal conservation plan to endangered mammals recommends to reconnect the Varadouro Canal by constructing aerial bridges for lion tamarins.

Another example of causal fragility is the correspondence established between the indirect threat “32% of the area of occurrence is not under implemented protection” and the direct threat “logging, especially palm heart and caixeta”. In 2008, a law in the state of São Paulo created a mosaic of 14 protected areas of both integral and sustainable use. Among these areas, the Lagamar de Cananeia State Park (40,758ha), the Ilha do Tumba Extractivist Reserve (1595ha), the Itapanhapima Sustainable Development Reserve (1242ha), and the Taquari Extractivist Reserve (1622ha) overlap or are neighbors to the São Paulo portion of the occurrence of L. caissara, according to Lorini and Persson's (1994) distribution. However, we did not measure the decrease of illegal logging to evaluate if the implementation of these protected areas decreased illegal logging.

The legacyThe alliances and partnerships between leaders and local institutions and their involvement with our work was the greatest legacy of our program. This process resulted in community achievements and changes in attitudes and positions. However, local actors participation and involvement and changes in positions and attitudes do not guarantee behavioral changes that favor the conservation of biodiversity, the final aim of our interventions (Holmes, 2003; Waylen et al., 2009). These changes depend on the establishment of conservation and sustainable development paradigms. To contribute to this process, it is important that we adopt a motivational, innovative, challenging, and facilitating position.

The finding that local actors’ application of Econegotiation was critical to reducing the threats to black-faced lion tamarins supports the hypothesis that conservation interventions are more successful if they understand and respond to institutions, culture, and local conflicts (Waylen et al., 2010; Redford et al., 2011; Peterson et al., 2013). Moreover, when it comes to the legacy of our work, it is worth reflecting on Conservation Biology and its scientific condition loaded with principles and values (Groom et al., 2006; Meine et al., 2006). What this means in terms of conservation of the threatened species is not simple to answer (Redford et al., 2011). In the case of L. caissara, our conceptual model explains the “minimum viable population,” a classic biological indicator, as a target condition, which reflects our biocentrism. This parameter is influenced by the common belief among conservation biologists that all species are valuable and important.

Maintaining ecological processes that assure the course of natural selection refers to another striking characteristic in Conservation Biology, namely its eternal vigilance (Meffe et al., 2006; Redford et al., 2011). The conservation of biodiversity and sustainable development in Ariri region, vital for the conservation of black-faced lion tamarins, deserves attention since the existence of various protected areas alone does not guarantee conservation (Kareiva et al., 2012). Therefore, we should always be aware of how the regional leaders and institutions respond to economic pressures, the use of natural resources, and the effects of global change.

Lessons learned and recommendationsConsidering the striking differences among communities, biomes, institutions, territories and their governance, and the species with which we worked, the first lesson is try to know the social, cultural, and economic profile of the territory in which we are working. This knowledge is fundamental for planning a conservation intervention program, and so is critical in defining threats to biodiversity and appropriate approaches for reversing them (Salafsky and Margoluis, 1999, 2004; Dietz et al., 2010; Waylen et al., 2010).

We will never have a complete perception of the region where we undertake of our conservation efforts, since we were external agents passing through that context and history. Thus, we recommend looking for strategies that help outline a design of that reality. In this sense, our experience indicates initial diagnostics as useful tools. When we started our work in the Ariri region in 2005, beyond the studies on L. caissara, we focused on getting to know the community and its dynamics. At that time, besides interviewing local leaders, we used curiosity about studies on tamarins as an opportunity for informal conversations. Many relationships of trust and respect stem from these moments. Initially, a continuous presence in the community and experience of local processes were fundamental to our acceptance. This process of acceptance by the community enabled us to understand that the actors that involved themselves in our actions looked for their own interests, and that these interests could be swayed toward conservation and sustainability via new opportunities and the establishment of new paradigms on conservation and sustainability.

The second lesson we learned pertained to the importance of a clear direction and the focus on our target and mission in all stages of the program, including its delineation. While it seems obvious, this direction is important so that we do not deviate and assign more value to activities and actions than to the goals of our conservation program. This clarity and commitment to goals also helps us position ourselves politically after inserting into the social context of the work region. Another fundamental factor is our conviction that it is possible to get close to achieving the target condition and that our work can make a difference in this process. Important is that our intervention must be understood from the beginning, the middle, and to the end. Furthermore, our work corroborates with other studies that suggests that many years of effort are necessary before we near our aim of integrating conservation and development (Berkes, 2004; Franks and Blomley, 2004).

The third lesson is that the consolidation of partnerships at all levels of discussion, local to international, is vital in conservation and development. Joining leaders and institutions that overlap in values and principles enables mediating and articulating actions that aim to reach common goals. Partnerships are important for countless reasons, from the implementation of a simple activity to achievement of goals, to obtaining the necessary financial resources for the work.

Over ten years, our team and that of an Italian Zoo were able to integrate conservation in situ and ex situ, despite the absence of a captive population for L. caissara. Aiming to overcome this challenge, we created the “Brazilian Corner” at the zoo, where visitors could get involved with in situ conservation of black-faced lion tamarin and its forest. The “Brazilian Corner” was a stage for annual “Save the Caissara” campaigns, which raised resources through diverse activities planned by zoo educators and the sale of craft products from Lagamar de Cananeia communities. This partnership was fundamental to continuing to plan and execute a decade of work.

The fourth lesson is that a participative and aggregative strategy, like Econegotiation, can act on direct and indirect critical threats – such as a lack of dialog between actors and local institutions – and give insight toward approaches and partnerships to reverse them. The change in the quality of relationships that began with the first Econegotiation brought people and institutions with common interests and values closer, motivating partnerships for approaches like “education and awareness,” “sustainable business,” and “community organization and mobilization”. The political and participative character of the network of actors that joined us gave legitimacy to our work in the sense that no actions were undertaken exclusively by the conservation program (Table 1).

The application and suitability of this strategy should adhere to the necessary discussion and planning during the entire process, making it necessary to involve conflict mediation professionals in the earliest stages. We recommend that participative strategies such as Econegotiation must be planned and undertaken in a reasonable time frame to be successful (in our case, around two years of previous work for each Econegotiation workshop). It is also important to remember that the Econegotiation does not end with the workshop, since our involvement is strategic to its continuation.

Awareness of the timeliness of our intervention – considering the greater time scale involved with the conservation of biodiversity and the role of natural selection on it – should be present in all phases of the work, and that is why we need goals and objectives with indicators. This understanding helped us, for instance, to respect the rhythm and way traditional inhabitants worked and materialized. This positioned us as motivators and facilitators as they overcame their challenges, for example, the need for artisans to learn about product pricing or for legal assistance to constitute and establish local associations.

Those lessons highlight two key points: (i) The relevance of planning, implementing and evaluation interventions on ICDPs, (ii) The effect of our work will be proportional to our ability to integrate into the local context and influence the conservation of biodiversity as an interest shared by diverse actors and leaders in the territory.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We are most grateful to the Parco Zoo Punta Verde, Italy, for its partnership and continuous support, without which this long-term work would not have been possible. We also thank: the Núcleo Oikos, Brazil, for its long term partnership and involvement; the Ariri community, Cananeia, São Paulo state, for its friendliness and involvement with the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas (IPÊ); Nelson C. Silveira Filho, Cecil Maya and Marcelo Limont to mediate the Econegotiations workshops; Gustavo de Paiva Resende Toledo for its support and involvement with the community based tourism initiatives; Conceição Silva and Elza Maria Lawson Dupré for its support and involvement in the handicraft iniciatives. Kaitlin Baird and Clinton N. Jen kins to review the first English version of this manuscript