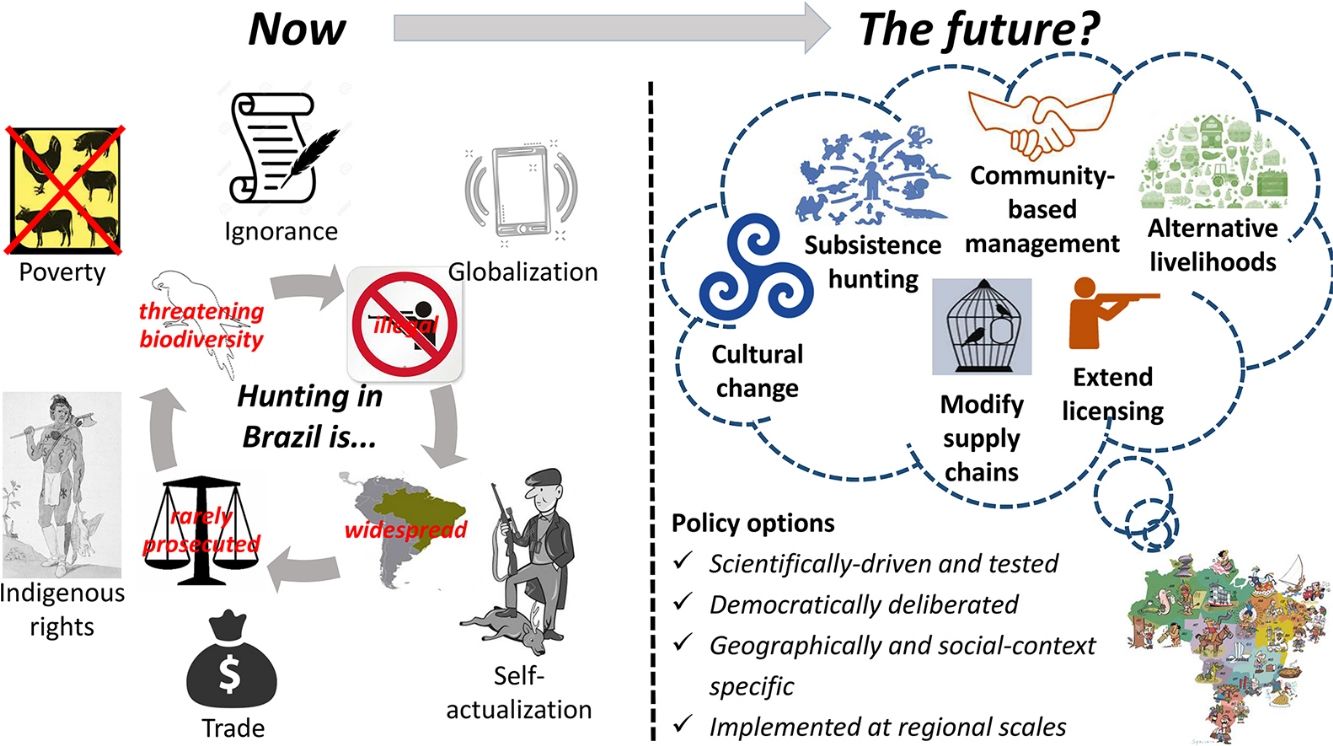

In Brazil most forms of hunting and keeping of wild animals are illegal, although they remain widely practiced and are deeply culturally embedded in many regions. The drivers of such widespread non-compliance are poorly understood and evidence to support future policy decisions is generally lacking. In this paper, we seek to stimulate a critical debate on how to deal with hunting in Brazil by analysing the main factors driving non-compliance with current legislation. This is particularly timely given that several amendments to existing legislation are currently under consideration. Our analysis suggests that, while there are no simple solutions to non-compliance, a targeted suite of the following policy options could improve the monitoring, sustainability and conservation consequences of hunting in Brazil: (i) simplifying the process to become a registered subsistence hunter; (ii) expanding participation in licensing schemes; (iii) investing in pilot studies and assessing their environmental and socioeconomic impacts; (iv) expanding community-based management programmes; (v) trailing education and social marketing campaigns. These policy options are geographically and social-context specific and would be most effectively be implemented at regional or sub-regional scales.

Nearly all countries have extensive legal frameworks designed to carefully regulate human interactions with the natural environment. Many of these laws have been carefully drafted to align with global treaties (such as the CBD and CITES) and specifically prohibit the over-exploitation or degradation of certain natural resources. Some countries, such as Brazil, go even further and prohibit most forms of hunting and keeping of wild animals. And yet… hunting is still remarkably widespread throughout Brazil (de Azevedo Chagas et al., 2015; El Bizri et al., 2015), prosecutions are rare (Barreto et al., 2009; Kuhnen and Kanaan, 2014) and fines resulting from prosecutions are hardly ever paid (da Silva and Bernard, 2016). Moreover, the very fact that it is illegal means that it is very hard to gather data about either the hunters or the species they are exploiting, leaving local conservation managers to make decisions in an information vacuum.

According to the Wildlife Protection Law (Law No. 5197/67), wildlife hunting and trade in Brazil is criminalized. However, the current law and its subsequent revisions (Law No. 7653/88) distinguish between predatory and non-predatory hunting. The first refers to commercial hunting and poaching and is fully criminalized. In contrast, non-predatory hunting (including subsistence hunting, hunting for controlling wildlife populations, hunting for scientific purposes, and recreational/sport hunting) should be regulated, monitored and controlled. Theoretically, the only barrier to legally practice non-predatory hunting in Brazil is to obtain a license – through this process is both costly and bureaucratic (Pinheiro, 2014). Given the lack of incentives for private individuals to engage with this process, most hunting in Brazil (whether predatory or non-predatory) continues to be unregulated and illegal with significant negative consequences for animal populations, biodiversity and ecosystem processes (Antunes et al., 2016; Cullen et al., 2001; de Araujo Lima Constantino, 2016; Tabarelli et al., 2010).

Recognizing the weaknesses of existing legislation, Brazil's congress is currently debating a new proposal (PL 6268/2016) which, if approved, will revoke the current Wildlife Protection Law and promote the creation of private hunting reserves. Significantly, the new proposal will not explicitly prohibit commercial hunting, and has the potential to increase wildlife trafficking and animal suffering. While supporters of the new legislation claim that it will finally regulate hunting in Brazil, many environmentalists see this as a retrograde step. Interestingly, while the new proposal was being debated, São Paulo's state government approved a law (PL299/2018) which ban all forms of wild animal keeping and hunting within the state. Such decision has direct impact on the control of the invasive wild pig in the state, which was previously regulated by a Federal Decree (Instrução Normativa Ibama 03/2013).

Whether (or not) there will be a change in the federal legislation, there is a broad consensus among academics, practitioners and wildlife managers that hunting is a major conservation issue in Brazil (Fernandes-Ferreira and Nóbrega Alves, 2017; Fernandez et al., 2012). From a technical perspective, there is a general lack of data about wildlife and population dynamics in Brazil and, more generally, in Latin America (Roper, 2006). Additionally, designing effective policies to protect wildlife and manage different species across megadiverse regions spanning from semi-arid and savannah environments (Caatinga and Cerrado) to the world's largest tropical wetland area (Pantanal) is extremely challenging (Alves and Souto, 2011). To further complicate this picture, hunting is culturally discouraged in much of Brazil, especially among urban populations (Marchini and Crawshaw, 2015). In contrast, the social acceptability of hunting is usually greater in rural areas where livelihoods are traditionally more reliant on the exploitation of natural resources (Gama et al., 2016; Bragagnolo et al., 2017a,b). Thus, the development of effective conservation strategies also requires identifying and assessing the relative importance of the factors that motivate illegal practices within specific socio-political and economic contexts (Duffy et al., 2016). Nevertheless, our understanding of why people hunt in Brazil is rudimentary a frequently anecdotal. For example, while poverty may drive subsistence hunting in some remote rural areas of poorest regions, hunting behaviour seems to cross socio-economic boundaries (El Bizri et al., 2015). Moreover, a perceived lack of enforcement could encourage non-compliance for economic gain, or even for social enjoyment and/or prestige (Regueira and Bernard, 2012).

In this context, enlarging our understanding of what is driving such widespread non-compliance is an important initial step towards developing more effective policies to deal with non-compliant behaviours and better supporting wildlife management across the country. In the following article, we consider the main factors which could be driving non-compliance with hunting legislation in Brazil with the aim of stimulating a critical debate on how to deal with hunting in the future.

Drivers of non-compliance with hunting legislationPerhaps the first prerequisite of compliance is being aware of rules. Ignorance of the law is among the most important drivers of non-compliance with environmental regulations (Winter and May, 2001). This might be compounded by high levels of social acceptability and participation: it could be considered rational to believe that an activity is legal if it is widely and freely practiced. Moreover, communication of legal obligations relating to hunting may be ineffective. For example, studies conducted in Nigeria (Adefalu et al., 2013) and Madagascar (Keane et al., 2011) indicate higher levels of ignorance about wildlife laws and policies among local hunters with no formal education, less educated individuals and those not involved with tourism and community-based resource management. Ignorance of hunting laws is a common reason for non-compliance, even in developed countries (Eliason, 2004), but may be especially problematic in areas where illiteracy is still high. Such a situation is prevalent in remote rural areas and poorer states of Brazil. Furthermore, even if prohibitions on hunting are recognized, some rural residents may lack a comprehensive understanding about its complex requirements and bureaucratic hurdles (i.e. the licensing system regulating non-predatory hunting) or they may associate hunting ban only inside Protected Areas (Bragagnolo et al., 2017a,b). Additionally, education campaigns and outreach activities aimed at raising public awareness about wildlife hunting are generally rare, and/or not effectively targeted. Public debates concerning illegal exploitation of natural resources and hunting are also sporadic and commonly addressed by a mixture of academics, conservationists, decision-makers and anti-poaching activists.

Poverty is another factor often considered as an underlying motivation for illegal wildlife hunting, the implication being that the rural poor are driven to hunt by the absence of livelihood alternatives and the comparatively cheap prices of wildlife products (Apaza et al., 2002; De Merode et al., 2004). However, since poor people may hunt for both subsistence (“cooking pot”) and income (“pocket book”) (Kahler and Gore, 2012), distinguishing between commercial hunting and subsistence hunting is very challenging (Duffy et al., 2016; Fa et al., 2002). In rural Africa for example, Brashares et al. (2011) showed that wildlife consumption follows a very complex rural-urban gradient that includes subsistence-based rural consumption (the poorest people from more isolated settlements consume more bush-meat), mixed subsistence-commercial hunting (small scale farmers), hunting for commercial urban markets (wealthier households in settlements nearer to urban areas consume more bush-meat), and even hunting for the international trade in bush-meat.

In Brazil, subsistence hunting is not technically illegal and is allowed on Indigenous Lands and poor rural areas as a means to ensure the rights of indigenous populations (traditional hunting) and to improve food security of rural people living in poverty. However, due to the current illegality of commercial hunting and the bureaucratic hurdles to officially register as a subsistence hunter, it is difficult to get accurate figures on the prevalence, geographic distribution or temporal trends of these activities. This is further complicate by poor management and enforcement with clear implications for wildlife, especially game species (Peres and Nascimento, 2006). Moreover, there is evidence that subsistence hunting is increasingly being coupled with commercial hunting as an alternative income source. For example, van Vliet et al. (2015) used questionnaires to reveal how urban hunters in the Amazon hunt for both subsistence and trade. Subsistence hunting and poverty should also be placed in the context of recent social changes. On one hand, the massive federally funded social programmes introduced in the early 2000s in Brazil (i.e. Programa Bolsa Família) have hugely improved the income of poor rural residents, potentially decreasing the ‘need’ to hunt for food. For example, Barboza et al. (2016) showed that the preference for bush-meat over livestock displayed by rural residents in northeast Brazil was more a matter of taste than a dietary necessity. In this region, preferences for wild meat are also traditionally shaped by climate since drought periods make bush-meat the only sources of protein due to crop losses and starvation of livestock and small domestic animals. Urbanization also contributed to change dietary habits and lifestyles blurring the distinction between urban and rural contexts and making processed and industrialized foodstuff more available and affordable even for traditional communities living in the most remote villages (Nardoto et al., 2011). Global urbanization processes are also contributing to changes in human values. For example, in some parts of the World the demand for wild animal products is escalating, driven by wealthier urban individuals who view bush-meat as a status symbol (Drury, 2011; East et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008). This situation is especially recognizable in the Brazilian Amazon, where several species such as, for example, the giant river turtle (Podocnemis expansa), have been transformed from a subsistence food for riverine people into a delicacy for high society (Schneider et al., 2011). Other studies point to how cultural drivers are key factors in shaping diet preferences and food-related behaviours of urban dwellers, cautioning about the increasing demand for bush-meat in Amazonian towns (Morsello et al., 2015).

Globalization has also increased the availability of modern weapons and accessories in remote areas, making hunting and trading strategies more efficient (e.g. mobile phones, etc.) and encouraging illegal commercial hunting and trade. In this context, hunting might no longer be driven by basic needs, but may increasingly become a recreational and/or commercial activity. This is certainly true in developed countries such as the United States where social welfare has dramatically reduced the necessity to hunt for poor rural residents, but where wildlife law violation occurs for diverse reasons including (among others) economic gain and recreational satisfaction (Eliason, 2004).

Self-actualization also plays an important role in shaping human behaviour (Maslow, 1943). It is often overlooked that many people hunt and fish because they enjoy it (recreational satisfaction) and such enjoyment is by no means limited to financially privileged and fully licensed individuals in developed countries (Sharp and Wollscheid, 2009). Sport hunters may also be motivated by social relations and the sense of belonging to a group or club (formal or informal). The latter is partially considered in Brazilian law which demands that each sport hunter must be affiliated to a registered shooting club. Hunting can be also practiced to gain prestige and to strengthen social relationships in small communities (Morsello et al., 2015). In Brazil, sport hunting is further perceived by some as having a noble status, reminding citizens of their colonial heritage (Nassaro, 2011). Moreover, recreational hunting may be a symbol of power and immunity from the law, especially for those people that have legal permission to possess firearms (i.e. police officers, security guards, members of shooting clubs).

The widespread acceptance of hunting as a recreational activity has broadly decreased in industrialized and urbanized contemporary societies since the early 1970s in response to shifting ethical and moral attitudes to human relationships with nature (McLeod, 2007; Peterson, 2004). Such concerns can make it difficult to legitimize hunting as a sport and/or as a component of a broader conservation strategy (Batavia et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2013). For example, animal rights activists may (reluctantly) accept killing animals for subsistence and food provisioning, but may be absolutely opposed to hunting for ‘fun’. Such attitudes may be in direct opposition to natural resource managers who recognize the role of recreational hunters in generating broader wildlife conservation and collective economic benefits and who seek to integrate their knowledge and rights into wildlife management policies (Dickson, 2009; Van de Pitte, 2003). In Brazil, mass media (magazines, newspapers, television and radio) has played a key role in changing public perceptions about hunting since the early 1980s by increasingly associating hunting and hunters with serious environmental problems (i.e. deforestation of the Amazon, biodiversity loss, etc.). As a result, Brazilian public opinion has been increasingly polarized among pro- and anti-hunting factions (Fernandes-Ferreira, 2014). This was clearly reflected in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, where animal rights activists and environmentalists co-opted a pro-environmental argument (lead contamination caused by the release of ammunition) to suspend sport hunting in the only region where it had been successfully implemented and managed since the 1970s (Lau, 2016). Indeed, it has been persuasively argued that sport hunting in Rio Grande do Sul contributed to: (i) protecting species (Nascimento and Antas, 1995); (ii) testing new management schemes (Efe et al., 2005); and (iii) generating information about the routes of migratory birds and, more generally, the spatial distribution of key species (Nascimento et al., 2000).

Outside of the now defunct example of Rio Grande do Sul, sport hunting in Brazil has been largely unregulated. There is also evidence that illegal sport hunting is growing across the country. El Bizri et al. (2015) detected an increase in posting of videos on YouTube related to sport hunting, identifying the hunters as predominantly wealthier urban residents and descendants of European countries. This pattern may be partially explained in terms of Brazilian urban residents who have recently migrated from rural areas and are still maintaining their rural identity. It is worth noting that many hunters have both a strong knowledge about game species and their ecology, and a deep relationship with landscapes and prey. In Brazil, ethnozoological studies have started to reveal the enormous value of this type of knowledge and its potential utility for improving biodiversity conservation and wildlife management (Alves, 2012). The majority of these studies have been in the Northeast region (Caatinga and Atlantic Forest of Northeast Brazil) where hunting pressure is higher (Fernandes-Ferreira, 2014) and where hunting is a strongly embedded cultural practice (Bragagnolo et al., 2017a,b).

Hunting might be so deeply culturally embedded that people disregard the law en masse. In other words, a law loses force (and is ignored) when it is perceived as criminalizing behaviours that fall within social norms. Geographically localized social surveys suggest that unregulated hunting is a common practice in many rural regions of different Brazilian ecoregions (Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2012; Fernandes-Ferreira and Nóbrega Alves, 2017; Gama et al., 2016; Teixeira et al., 2014). Moreover, illegal trapping/hunting of wildlife is often socially acceptable (Alves et al., 2009; Morcatty and Valsecchi, 2015) and frequently practiced even inside and surrounding protected areas (de Carvalho and Morato, 2013; Ferreira and Freire, 2009). Despite very limited resources, seizures of wild animals in Brazil are frequent and probably represent the tip of a very large ‘iceberg’ (de Azevedo Chagas et al., 2015). Ineffective enforcement of environmental policies in Brazil is also a major limitation, since it does not obviously contribute to increased compliance or behavioural change (Barreto et al., 2009; da Silva and Bernard, 2016). Moreover, corruption is perceived by many Brazilians as the main cause of poor enforcement of environmental laws (Aklin et al., 2014).

Ultimately, illegal hunting in Brazil is similar to many other regions of the world, being characterized by considerable overlap between hunting for subsistence, for income generation, and for recreation (Loveridge et al., 2006; Morsello et al., 2015; Sánchez-Mercado et al., 2016). Other less common motivations may include thrill killing, trophy poaching, protection of self and property (human-wildlife conflicts), poaching to assert a traditional right and as a form of protest against a disputed regulation (Muth and Bowe, 1998) or a conservation policy (Mischi, 2012). In other words, there are multiple possible reasons for the high level of non-compliance with hunting regulations in Brazil and very little data on which to base a robust and well-targeted policy response. In such circumstances it is important to return to first principles, using multiple sources of data to identify which suite of policy measures may be most appropriate in any given cultural context.

Policy options and recommendationsIn situations where an illegal activity is very widely practiced and culturally embedded, an obvious and potentially politically attractive solution would be to revoke the laws or decriminalize the behaviour. This is partially what the new legal amendment (see above) is proposing for commercial hunting. Nonetheless, a radical change such as this could have unintentional consequences for overexploited species, altering population and ecological dynamics and ultimately affecting ecosystem functions and services. This may be particular true in many tropical and subtropical regions (i.e. rainforests) where population densities of larger species are typically low (Roper, 2006) and illegal hunting remains one of the main impacts driving species’ extinction (Bodmer et al., 1997; Corlett, 2007; Laurance et al., 2006). In this context, legislators and the Brazilian society more generally should strategically evaluate the trade-off between decriminalizing some types of hunting and preserving biodiversity, i.e. to what extent a social group (i.e. hunters) could be benefited (and thereby “decriminalized”) over the common right to preserve a species, an ecosystem or an ecological function. Solving this ethical question in Brazil is by no means straightforward, especially in the current climate of divided public opinion and the absence of comprehensive information about hunting and its consequences. Assuming that some citizens choose not to hunt (or hunt less frequently) due to fear of prosecution, decriminalization of some types of hunting could significantly increase hunting pressure in some areas and for some species. Nevertheless, we would argue that relatively minor changes to legislation might be sufficient to improve monitoring, discriminating distinct types of hunting and hunters, and bringing more hunters into existing legal structures.

We strongly advocate a more flexible, open-minded and scientifically-driven approach by policy-makers, protected area managers, environmental activists and animal defenders, and generally recommend the adoption of one or more of the following options depending on the specific cultural and environmental context: (i) simplifying the process to become an officially registered subsistence hunter; (ii) expanding participation in licensing schemes; (iii) linking hunting to community-based wildlife management programmes; (iv) introducing alternative livelihoods in areas with high levels of illegal subsistence hunting; (v) modifying hunting supply chains through substitution; (vi) trialling broad-based education and social marketing campaigns aimed at key demographics. Policy options (i) to (iii) can be applied where hunting is considered desirable and needs to carefully regulated and monitored. Policy options (iv) to (vi) are applicable to situations where illegal hunting needs to be controlled or where hunting pressure needs to be reduced.

Simplifying the process to become an officially registered subsistence hunterBrazil is famous for its complex bureaucracy, and any changes in hunting legislation would ideally be accompanied by a streamlining of legal processes. An obvious starting point would be to simplify the procedure to become a subsistence hunter and to clearly define the criteria (e.g. minimum body size, hunting seasons, sustainable quotas, etc.) to limit overexploitation and defaunation. Of course, establishing more rigorous criteria for subsistence hunting may not completely reduce human pressure, though it could considerably improve monitoring and may generate a small amount of funds and information about species biology and population dynamics. Considering the mega-biodiverse status of Brazil, suitable data should be gathered for target species, habitats and biomes (i.e. Amazon, Pantanal, Atlantic rainforest). An example of the type of data needed was documented by Jerozolimski and Peres (2003), who showed that mammal species above about 6.5kg are the preferred quarry of subsistence hunters in neotropical forests of the Southern Amazon. Similarly, Parry et al. (2009) demonstrated that subsistence hunters of Brazilian Amazon preferred primary forest because requiring the lowest catch-per-unit-effort and allowing other traditional extractive activities. Although this may translate into greater pressure on many large vertebrates, regulating such subsistence hunting in primary forests may help contain large-scale deforestation by requiring a greater integration with other conservation and land-use policies (e.g. Forest Code, Protected Areas planning, etc.).

There may also be lack of institutional flexibility making it difficult to drive through changes that challenge long established protocols and mind-sets within regulatory bodies such as the Brazilian Institute for the Environment (IBAMA). Following a broader decentralization process (since 2011), legal responsibility for surveillance and enforcement of administrative penalties involving flora, fauna and environmental licensing has been transferred from federal (IBAMA) to state and municipal environmental agencies (Lei Complementar 140). Considering the uneven institutional capacity across the country (see for example Sánchez, 2013; Malhado et al., 2017), several states and/or municipalities may be not prepared to implement an enforcement system for controlling hunting due to local political pressures, corruption and technical and financial constraints. In this context, a blanket loosening hunting legislation across the country would be impractical. Moreover, given Brazil's drawn-out economic crisis and the bleak prognosis for economic growth in the medium term, the more likely scenario is that federal and state budgets will be frozen or even reduced, further depleting resources for monitoring and enforcement.

Expanding participation in licensing schemesIf hunting is legalized in Brazil – as proposed by some political projects – one of the main challenges will be to create a system of licencing of sites and individuals. Such schemes are extremely effective for improving monitoring and may also provide considerable income for conservation and wildlife management. For example, a quantitative study from the United States estimated that in 2011 hunters spent $796 million on licenses and permits, and that state and provincial agencies were able to invest this money to restore and manage wildlife and habitats, monitor and study populations, maintain access to lands for public recreation, build shooting ranges, and support hunter education programmes (Arnett and Southwick, 2015). Nevertheless, the feasibility of expanding licensing schemes for sport hunting in Brazil will depend upon the size of the market and, specifically, whether it would be large enough to generate significant income for management and conservation (Roper, 2006). Lack of institutional capacity (see above) may be also critical to ensure effective enforcement and control.

Another potential challenge to expanding licensed hunting in Brazil is that private hunting reserves require a high social acceptability, and would therefore be restricted to regions where recreational hunting already has high levels of public support (e.g. the southern states of Brazil). In this context, developing ethical codes regulating recreational hunting behaviours could both increase the social legitimacy of sport hunting and establish a set of behavioural norms for Brazilian hunters.

Expanding participation in licenced hunting could also be achieved by coupling hunting with tourism, a strategy that has sometimes been effective in southern Africa (Di Minin et al., 2016; Naidoo et al., 2016) where big game animals are a sufficiently strong draw to attract foreign tourists. However, such schemes typically have a weak impact on illegal hunting (Mateo-Tomás et al., 2015) and in many developing countries they are often linked to corrupt practices (Leader-Williams et al., 2009). Also, the lack of social and ecological data in Brazil means that prioritizing areas for implementation of such schemes would not be straightforward. A good starting point would be to identify regions where high recreational hunting value species occur (cf. Correia et al., 2016) and where ecotourism enterprises are already well-established (e.g. the Pantanal). Pilot areas could then be identified among PAs designated for sustainable use, such as Extractive Reserves (Reservas Extrativistas). In Zambia, similar types of areas have been shown to be more profitable for trophy hunting, while also acting as “wildlife sources” for restocking game populations (Naughton-Treves et al., 2005).

Another area where licencing could be expanded with potentially positive consequences for conservation is hunting to control invasive species, especially given the widespread presence of non-native species in otherwise conserved areas (Pedrosa et al., 2015; Sampaio and Schmidt, 2014). However, if hunting is to be considered as an acceptable strategy for controlling invasive species, public attitudes may need to be seriously considered. Hunting of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) has been introduced in South Brazil for population control and it is regulated by a National Plan (Plano nacional de prevenção, controle e monitoramento do Javali no Brasil). However, there are strongly divergent opinions on this practice. In the Pantanal, local people value pig hunting as a highly traditional activity, and seem to prefer hunting feral pigs with positive consequences for native wildlife (Desbiez et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2005). However, in other regions of southern Brazil (e.g. São Paulo State) wild pig hunting has already been banned, and its return is very unlikely in the face of pressure from animal rights activists. In this case, demonstrating the benefits of hunting for controlling wildlife populations and protecting native wildlife may be not enough to increase public acceptability and additional measures such as the development of ethical hunting codes that address the concerns of local citizens may also be required.

Expanding participation in licensing schemes would greatly facilitate monitoring. Despite the requirement of Brazilian Wildlife Protection Law for collecting data on population dynamics and monitoring wildlife to establish sustainable wildlife management practices, scientific information is very patchy for potential target species (Roper, 2006). It is possible that local and traditional knowledge about key species could be combined with scientific data to reduce this shortfall (see Van Holt et al., 2010), though this would create a new set of challenges. Moreover, increasing participation in licenced schemes would, in isolation, be insufficient to effectively control hunting pressure. To do this, a more comprehensive approach would be required that carefully demarcated licensed hunting areas, invested in enforcement and, where appropriate, introduced bag limits and off-seasons according to the specific characteristics of each biome and its wildlife populations.

Linking hunting to community-based wildlife management programmesAnother potential approach to regulate hunting is by closely linking the practice to well-designed community-based wildlife management programmes (Campos-Silva and Peres, 2016). There have been several successful examples of sustainable use and population recovery of aquatic megafauna in the Amazon adopting a community-based management approach, notably the recovery of the giant Arapaima which was almost extinct in many Amazon floodplains (Castello et al., 2009; Petersen et al., 2016) and the associated increase in many other overexploited freshwater species with natural and economic value (Arantes and Freitas, 2016). Besides its clear conservation value, this management scheme has also proven effective in alleviating poverty, improving welfare, social security and social capital of local communities (Campos-Silva and Peres, 2016). Similar schemes that directly involve local communities could potentially be implemented and tested for the management of game species in other Brazilian biomes, especially where the presence of indigenous people and traditional communities is still high (e.g. Pantanal).

Introducing alternative livelihoods in areas with high levels of illegal subsistence huntingThe above proposals are based on the proposition that the best way to control hunting is to officially recognize it as a legitimate practice and to adaptively control it through regulation and monitoring. However, in many parts of Brazil it may be both socially desirable and environmentally preferable to focus on reducing hunting pressure (legal and illegal). An obvious way to do this is to address the ultimate drivers of subsistence hunting, such as rural poverty. Poor people in rural areas of developing countries often bear the main costs of conservation initiatives, both directly in terms of unfair distribution of benefits and indirectly from the opportunity cost of land and resource uses foregone (Roe and Elliott, 2006). Living with wildlife often represents a further threat to their lives and livelihoods (e.g. crop destruction, disease risks and livestock predation) (Spiteri and Nepal, 2008). This is part of the rationale for integrating poverty reduction goals into conservation policies in many developing countries through strategies such as pro-poor wildlife tourism, community based wildlife management, sustainable ‘bush-meat’ management, pro-poor conservation, and integrated conservation and development projects. African countries have been particularly targeted by projects aiming at introducing alternative livelihoods for reducing the dependence of local communities on natural resources and bush-meat. Nevertheless, information on the general success of such projects on illegal hunting is very limited and narrow (SCBD, 2011), with success largely dependent on specific institutional, ecological and developmental conditions (Adams et al., 2004; Sanderson and Redford, 2004).

A feasible starting point for assessing alternative livelihood policy options in Brazil would be to conduct pilot studies and test alternative schemes. Such a strategy would require, as a pre-requisite, detailed information on the socioeconomic drivers of hunting and bush-meat consumption in key areas and regions. For example, recent studies based on interviews with hunters and local people in Northeast Brazil showed that hunted species included mammals for bush-meat, birds for pets and commerce and reptiles for zootherapy and control hunting (Alves et al., 2012; de Souza and Alves, 2014; Fernandes-Ferreira et al., 2012; Pereira and Schiavetti, 2010). In similar context, promoting small-scale projects close to wildlife areas to integrate family income through, for example, honey production, crafts production, nurseries and food-crop production has been demonstrated a successful alternative to alleviate hunting pressures and diminish food insecurity (Lindsey et al., 2013). Another option aimed at alleviating poverty and reducing bush-meat hunting is the adoption of a local business-based approach such as the Community Markets for Conservation project (COMACO) developed with local communities surrounding national parks in Zambia (Lewis et al., 2011). COMACO creates networks of rural trading, training targeted households (the least food-secure people and illegal wildlife poachers) in sustainable agricultural practices and rewarding them with premium prices for their produce, turning it into high-value food products which a social enterprise sold across the country. Such a model could be tested, for example, in areas surrounding natural reserves in Northeast Brazil where there is the greatest pressure on wildlife and where there are low levels of food security due to the extreme climatic conditions and the high levels of social acceptability towards exploitative illegal activities (Bragagnolo et al., 2017a,b).

Modifying hunting supply chains through substitutionAnother way to reduce hunting pressure is to remove some of the financial incentives for hunting and wildlife trade by modifying supply chains. There is good evidence from other parts of the world that captive breeding can reduce the demand for wild caught birds (Jepson and Ladle, 2005, 2009). However, breeding expertise takes time to build up and may be slow to generate economic returns. Moreover, the existence of a black market (in wild-caught birds, for example) could undermine new business ventures. Although captive breeding or ranching is unlikely to work for popular Brazilian bush-meat species such as armadillos, it may be viable for species such as the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) where there is both global expertise and an abundance of successful and economically viable interventions on closely related species (Gelabert et al., 2017; Nickum et al., 2018). Finally, there may be considerable bureaucratic hurdles that need to be overcome – Nogueira and Nogueira-Filho (2011) highlight the potential difficulties involved in engaging governmental and/or non-governmental agencies to support the captive rearing of peccaries in the neotropics.

Changing cultural attitudes to huntingA more ambitious and potentially far-reaching approach to Brazil's hunting problem would be to change the culture of illegal hunting in rural Brazil through education and social marketing campaigns. While education-based interventions are more effective in changing opinions of unformed people or individuals with scarce knowledge about conservation (Leisher et al., 2012), social marketing campaigns could primarily play a key role and driving changes on individual behaviours when social norms and taboo are critical behavioural drivers (Veríssimo et al., 2012). The high levels of smart phone use and internet coverage in Brazil mean that there are ample opportunities for public outreach through social networks and judicious use of celebrity endorsements. There is also scope for aligning anti-hunting campaigns with more visible public concerns, especially related to diet and health (Challender and MacMillan, 2014). For example, recent studies in Vietnam advocate the use of customer-target campaigns as a long-term strategy to deter wild products consumption and trade (Drury, 2011; Shairp et al., 2016). The recent mosquito-borne zika and yellow fever outbreaks have sensitized the Brazilian public to the dangers of animal-borne diseases. The threat of zoonoses such as Leprosy (potentially caught from armadillos and monkeys), Chagas disease (armadillos), psittacosis (macaws) and leptospirosis (wide variety of mammals) could potentially be used to illustrate the public health dangers associated with the handling and eating of wild birds and mammals (Gruber, 2017). At the same time citizens should be further informed and became more aware about the environmental impact of intensive livestock production since changes in animal product consumption (wildlife meat vs. industrial livestock products) may have harmful consequences on the environment, ultimately contributing, for example, to increase deforestation and water consumption (Abbasi and Abbasi, 2016).

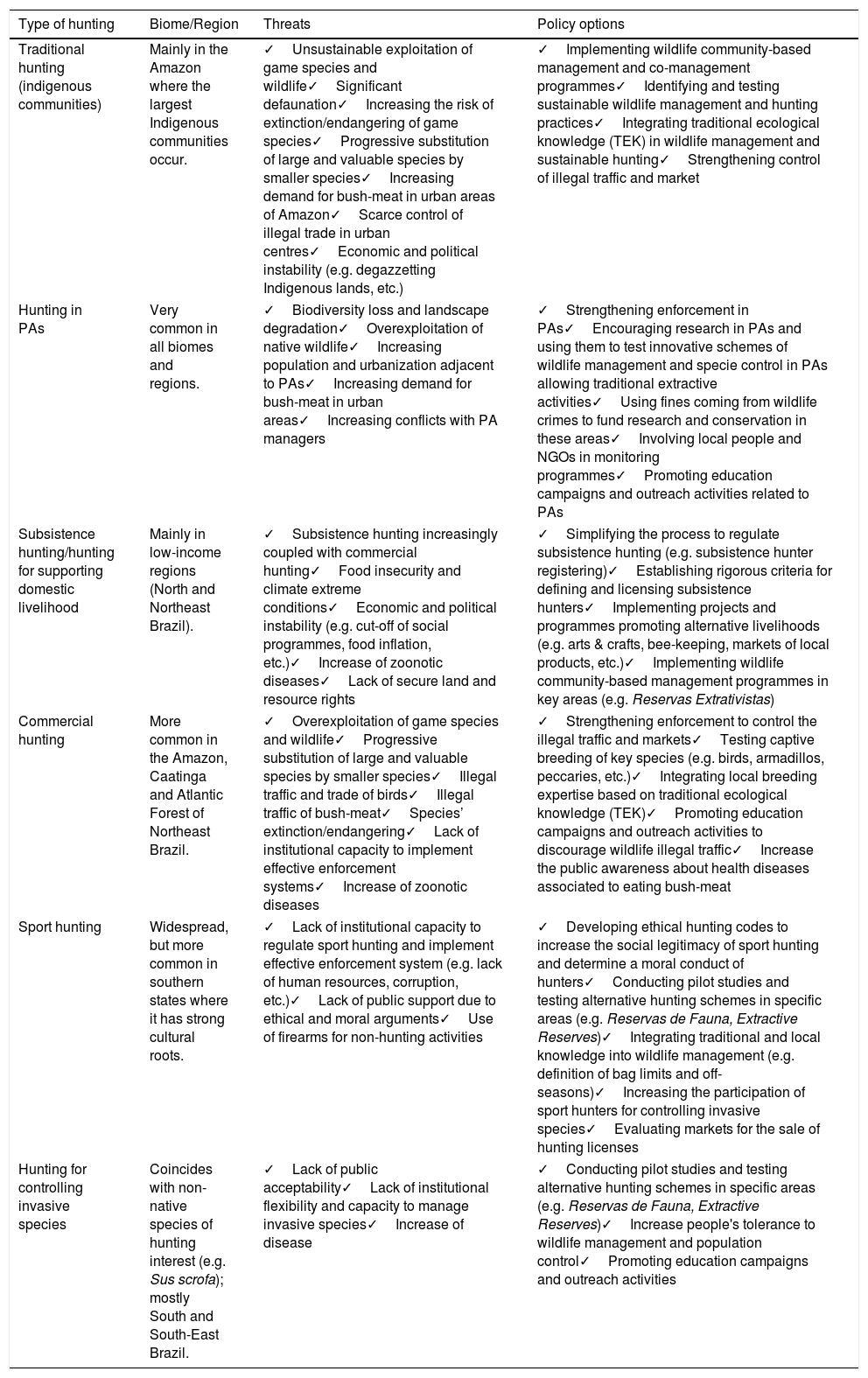

ConclusionsDebating an issue such as hunting in Brazil will be not straightforward until we have accurate data on its prevalence, and geographic and temporal trends and we understand why people are hunting. Nevertheless, there are several general principles that can be immediately applied. Firstly, due to its continental size and diversity, wildlife management and hunting in Brazil needs to be geographically and social-context specific (e.g. bird trapping for the cage bird trade in northeast Brazil, jaguar hunting by farmers in the Pantanal and Amazon, armadillo hunting for food in the Cerrado). Secondly, different types of hunting need to be clearly defined, assessed and regulated according to context, evaluating likely threats and considering different policy options (see Table 1). Finally, the gap between scientific evidence and policy decisions should be closed (see Azevedo-Santos et al., 2017), including the political will to develop legal instruments integrating different policy sectors (e.g. establishing some experimental management programmes in protected areas, assessing the environmental effects of social and poverty alleviation policies, establishing land-use based strategies, etc.). Achieving any of these actions requires increased investment in research and the generation of evidence-based support for effective managing wildlife. More efforts are also required for promoting education and human conservation management, assessing the sociocultural viability of legal hunting and identifying the social value of native species and biomes, by incorporating human dimensions into wildlife management. Finally, appropriate policy options unquestionably require being broadly and democratically debated and decided, avoiding top-down bureaucratic approaches and political manoeuvres using pseudoscientific promises to please privileged lobbies and/or deliver short-term mandates.

Policy options and threats for different types of hunting and region of occurrence.

| Type of hunting | Biome/Region | Threats | Policy options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional hunting (indigenous communities) | Mainly in the Amazon where the largest Indigenous communities occur. | ✓Unsustainable exploitation of game species and wildlife✓Significant defaunation✓Increasing the risk of extinction/endangering of game species✓Progressive substitution of large and valuable species by smaller species✓Increasing demand for bush-meat in urban areas of Amazon✓Scarce control of illegal trade in urban centres✓Economic and political instability (e.g. degazzetting Indigenous lands, etc.) | ✓Implementing wildlife community-based management and co-management programmes✓Identifying and testing sustainable wildlife management and hunting practices✓Integrating traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in wildlife management and sustainable hunting✓Strengthening control of illegal traffic and market |

| Hunting in PAs | Very common in all biomes and regions. | ✓Biodiversity loss and landscape degradation✓Overexploitation of native wildlife✓Increasing population and urbanization adjacent to PAs✓Increasing demand for bush-meat in urban areas✓Increasing conflicts with PA managers | ✓Strengthening enforcement in PAs✓Encouraging research in PAs and using them to test innovative schemes of wildlife management and specie control in PAs allowing traditional extractive activities✓Using fines coming from wildlife crimes to fund research and conservation in these areas✓Involving local people and NGOs in monitoring programmes✓Promoting education campaigns and outreach activities related to PAs |

| Subsistence hunting/hunting for supporting domestic livelihood | Mainly in low-income regions (North and Northeast Brazil). | ✓Subsistence hunting increasingly coupled with commercial hunting✓Food insecurity and climate extreme conditions✓Economic and political instability (e.g. cut-off of social programmes, food inflation, etc.)✓Increase of zoonotic diseases✓Lack of secure land and resource rights | ✓Simplifying the process to regulate subsistence hunting (e.g. subsistence hunter registering)✓Establishing rigorous criteria for defining and licensing subsistence hunters✓Implementing projects and programmes promoting alternative livelihoods (e.g. arts & crafts, bee-keeping, markets of local products, etc.)✓Implementing wildlife community-based management programmes in key areas (e.g. Reservas Extrativistas) |

| Commercial hunting | More common in the Amazon, Caatinga and Atlantic Forest of Northeast Brazil. | ✓Overexploitation of game species and wildlife✓Progressive substitution of large and valuable species by smaller species✓Illegal traffic and trade of birds✓Illegal traffic of bush-meat✓Species’ extinction/endangering✓Lack of institutional capacity to implement effective enforcement systems✓Increase of zoonotic diseases | ✓Strengthening enforcement to control the illegal traffic and markets✓Testing captive breeding of key species (e.g. birds, armadillos, peccaries, etc.)✓Integrating local breeding expertise based on traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)✓Promoting education campaigns and outreach activities to discourage wildlife illegal traffic✓Increase the public awareness about health diseases associated to eating bush-meat |

| Sport hunting | Widespread, but more common in southern states where it has strong cultural roots. | ✓Lack of institutional capacity to regulate sport hunting and implement effective enforcement system (e.g. lack of human resources, corruption, etc.)✓Lack of public support due to ethical and moral arguments✓Use of firearms for non-hunting activities | ✓Developing ethical hunting codes to increase the social legitimacy of sport hunting and determine a moral conduct of hunters✓Conducting pilot studies and testing alternative hunting schemes in specific areas (e.g. Reservas de Fauna, Extractive Reserves)✓Integrating traditional and local knowledge into wildlife management (e.g. definition of bag limits and off-seasons)✓Increasing the participation of sport hunters for controlling invasive species✓Evaluating markets for the sale of hunting licenses |

| Hunting for controlling invasive species | Coincides with non-native species of hunting interest (e.g. Sus scrofa); mostly South and South-East Brazil. | ✓Lack of public acceptability✓Lack of institutional flexibility and capacity to manage invasive species✓Increase of disease | ✓Conducting pilot studies and testing alternative hunting schemes in specific areas (e.g. Reservas de Fauna, Extractive Reserves)✓Increase people's tolerance to wildlife management and population control✓Promoting education campaigns and outreach activities |

CB is currently supported by CNPq (PDJ grant number 420569/2017-0). RAC is currently supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BPD/118635/2016). JVC-S is supported by a CAPES post-doctoral grant (Ref. 1666302). RJL and ACMM are respectively supported by CNPq (#310953/2014-6 and #310349/2015-0). EB is supported by a CNPq fellow grant.