There are various approaches to rewilding, corresponding to different socio-ecological and policy contexts. Most South American ecosystems have experienced Pleistocene and historical defaunation and the functional persistence of many areas will depend on restoration and rewilding. Rewilding is not seen as a priority or as a tool for restoration in South America, but we argue that several concepts could potentially be adapted to their contexts to respond flexibly to developing socio-ecological conditions. Here, we consider 10 questions that rewilding projects should consider, and we provide examples of how these questions are relevant to South America and how they have been answered already, in some cases. The 10 questions include: What role should humans play in rewilding projects? How can society deal with "monsters"? Is there a rationale for non-analogue rewilding? How do we justify baselines? Is it possible to do rewilding with small species? What is the right scale for a rewilding project? Should rewilding projects worry about sample size and pseudo-replication? When should we rewild carnivores? Do we need to distinguish rewilding from safari parks and zoos? What should be included in integrated monitoring and assessment? The questions we raise here do not have general answers optimal for all situations, but should be answered with reference to the socio-ecological conditions and transformational possibilities in different areas of South America.

Rewilding is one of the most vigorously debated topics in conservation (Nogues-Bravo et al., 2016; Rubenstein and Rubenstein, 2016; Svenning et al., 2016; Lorimer et al., 2015; Caro and Sherman, 2009; Fraser, 2009), despite, or perhaps because of, a lack of agreement about how it is defined and applied. Perhaps the broadest definition is restoration through reintroduction (Sandom et al., 2012), usually of one or more animal species that became recently extinct (in a historical context) in the intervention area and, more rarely, of ecological surrogates for globally extinct species. Due to their ability to capture the public imagination, rewilding projects are likely to expand dramatically in both number and scope over the following decades (Corlett, 2016). Some will be well controlled, carefully monitored and painstakingly documented within the academic literature. Perhaps the majority will not, being sponsored by individuals and organizations whose over-riding motivation is to recreate past worlds. Most rewilding projects, and surrounding debates, are currently located in Western Eurasia and North America. In the South American context, the distinction between rewilding and species reintroduction is not always well-developed. Here we examine how South American initiatives could position themselves in the design of rewilding projects. We do not attempt to tell South American (or any other) rewilders what they are doing or what they should be doing, but attempt to trace the main influences and questions that need to be considered in order to develop site-specific applications of rewilding. Like most managers who actually pursue rewilding approaches (Gooden et al. in prep.), we believe that contextual and site-specific interpretations will be more successful, and better for nature, than command-and-control approaches with one-size-fits-all definitions and recommendations.

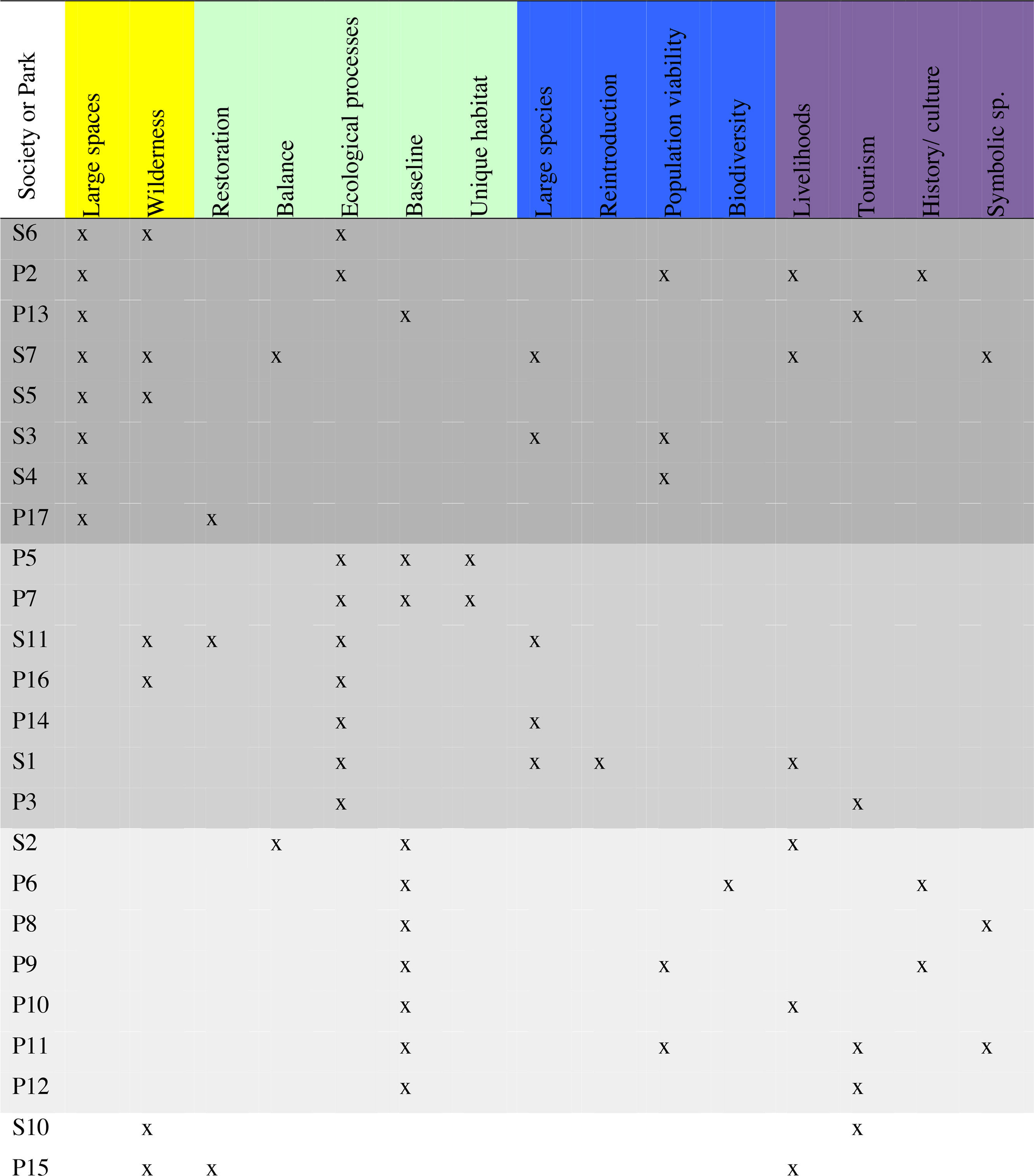

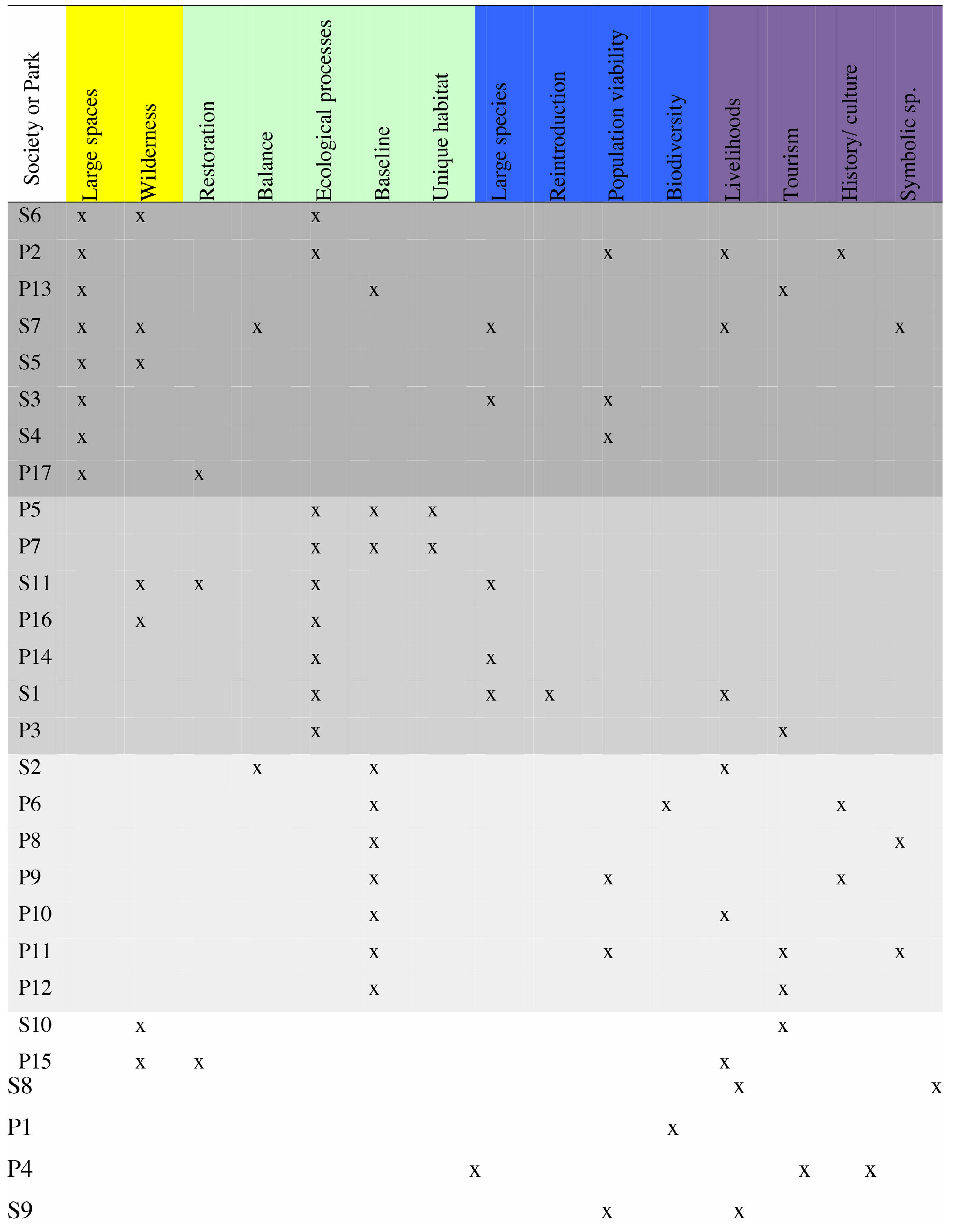

Two major strands of thinking underpin current trends in rewilding. The ‘Herbivore school’ is primarily interested in the relationships between large herbivores and vegetation (Martin, 1969; Vera, 2000; Galetti, 2004; Zimov, 2005). Conceptually this approach draws on predominantly European experiences with habitat restoration in cultural landscapes using domestic livestock (Van Uytvanck and Verheyen, 2014) (Fig. 1). In contrast, the ‘Carnivore school’ is characterized by an emphasis on conserving very large tracts of land to support top predators and their prey (Soulé and Noss, 1998; Foreman, 1998), and strongly draws on North American cultural mythology of wilderness. However, the use of the term rewilding in applied projects does not necessarily follow these ideological or geographical lines. We surveyed the mission statements of protected areas and societies (see Table 1) that either (1) describe themselves as doing “rewilding”, (2) are described in the academic literature or the popular press as doing “rewilding”, or that (3) have similar goals and use recognisably similar language as compared to organizations fitting either of the above criteria. Based on a content analysis, three main groupings emerged: organizations that focus on baselines, those that focus on ecosystem processes, and those that focus on conserving large spaces. These groups were not characterized by a particular geographical location. Jørgensen (2015) similarly finds a large variation of ideas contained within academic research and popular writing on rewilding.

Societies (S) and parks (P) that engage in rewilding or similar conservation activities, assorted according to their mission statements. Keywords are organized according to themes: Space and wilderness, ecological bases for rewilding, species-oriented concepts, and cultural and social considerations. One group of organizations can be identified that refers to large spaces (top shaded section). The second two groups can be defined by references to restoring or preserving ecosystem processes, and references to ecological baselines (middle shaded sections). Names of each organization are listed in Appendix1.

A focus on ecosystem processes implies a functionalist approach (focusing on ecological functions rather than species identities, cf. Callicott et al., 1999) and organizations with this focus make little mention of cultural or social goals. In contrast, a focus on baselines suggests a more compositionalist emphasis (that is, focused on what species are present), and these organizations also had a greater emphasis on cultural and social goals. These differences may reflect the implicit assumption that ecosystem functioning is intended to benefit humans (e.g. ecosystem services) while a compositionalist approach requires a more explicit, additional justification of social value. In this context rewilding in practice appears less an ideological stance and more a label co-opted to attract public attention to existing approaches responding to a range of concerns. This capacity to engage the public's imagination, while often ignored in the academic conservation literature, is perhaps the key aspect that differentiates rewilding from more traditional initiatives labelled as species reintroductions or habitat restoration.

It is important to note that there is no particular necessity to promote rewilding as a conservation approach in South America; South American conservationists might develop their own conservation approaches based on other philosophies and policy contexts. Nonetheless, rewilding responds to a set of ecological problems present on the continent, and designing species reintroductions to produce ecological restoration and social change, forming variations on rewilding, could be a valuable complementary strategy that is responsive to social dynamics of land use. Major South American ecosystems, including rainforests, seasonally dry forests, savanna and open woodlands, sclerophyllous forest, wetlands, shrublands and grasslands are in urgent need of restoration and improved conservation and management (Naranjo, 1995; Armesto et al., 1998; Cardoso da Silva and Bates, 2002; Mayle et al., 2007; Grau and Aide, 2008; Newton et al., 2012; Root-Bernstein and Jaksic, 2013; Ribeiro et al., 2015). These ecosystems have experienced significant defaunation, both during the Pleistocene-Holocene megafaunal extinctions (Cartelle, 1999; Guimarães et al., 2008) as well as due to modern land use and land cover change (Armesto et al., 2010; Jorge et al., 2013) and unregulated resource extraction often driven by telecouplings to more-developed economies (Gasparri and Waroux, 2015; Young et al., 2016; Nolte et al., 2017). As in Europe, rewilding could offer an opportunity to reassess the modern and traditional elements of socio-ecological systems and human relations to other species. At the same time, the social context for conservation and land management is significantly different from North America and Europe. For example, issues of indigenous rights and indigenous land tenure, governance, and traditional land uses are much more politically relevant and sensitive in many areas of South America as compared to North America (Stocks, 2005; Dove, 2006). Poor non-indigenous settlers or peasants are also an important group, and rural underdevelopment is common throughout the region (Kay, 2006).

These cultural differences mean that North American and European perspectives on rewilding may have considerably less traction among South American conservation constituencies. As an illustration, while the notion that there are large areas of “untouched wildland” is a recurrent theme in colonial accounts of South America, such a framing would be strongly and publicly contested by indigenous groups. By contrast, many European models of rewilding are built around developing alternate conservation and rural livelihood models on abandoned farmland or other available landholdings. These models constitute a clear attempt to reconfigure land management practices and human relationships to the land in the face of changing socio-economic situations and unsatisfactory conservation management regimes (Navarro and Pereira, 2012; Jepson, 2016). In South America, land use practices in many areas reflect a strong colonial legacy combined with a more recent imposition of neo-liberal principles. There are also large areas (e.g. the Amazon region) with a strong indigenous presence and a greater emphasis on traditional land-use practices. In other words, the problems that need to be solved and the systems that society is embracing or reacting against are different to those encountered in Europe or North America. By extension, South American rewilding will need to draw on a different sub-set of arguments and, as in Europe and North America, will be strongly shaped by what is possible to set up and maintain.

South American rewilding projects could position themselves to provide comparative ecological or socio-ecological case studies to rewilding projects in the Northern Hemisphere, requiring careful consideration of scientific issues. Alternatively, new projects may wish to formulate creative and novel modes of framing and integrating social and ecological issues, to form contextually tailored conservation approaches. The plethora of existing approaches to integrating people with conservation management—exclusion, participatory management, community based conservation, payments for ecosystem services, etc. (Berkes, 2004; Büscher and Dressler, 2012), implies that many other such models could also be developed in the future, drawing, for example, on indigenous practices. Such an approach could make important and novel contributions to regional and global conservation practice. Such decisions are non-trivial and require a deep understanding of the complex issues surrounding the concept and contemporary practice of rewilding. To facilitate this process we have identified 10 key questions that we think any new South American rewilding project should consider:

Question 1: What role should humans play in rewilding projects? The idea of “wild” implies (to some people) areas that have no significant human presence and should be maintained in this state. However, the cultural assumptions underlying this image of wilderness are constantly being challenged (Denevan, 2011; Cronon, 1996). Rewilding is often associated with a shift towards passive management (also called “non-intervention management”) and “natural experiments” in which ecosystem processes are allowed to run their course with very limited or no further intervention (Navarro and Pereira, 2012). Many rewilding proponents would reject the possibility of combining rewilding with agricultural production, for example. However, we would argue that rewilding inherently involves humans, and can be thought of as a socio-ecological experiment where the social variables are open to investigation (Lorimer et al., 2015). For example, rewilding projects could draw inspiration from Anthropocene baselines rooted in cultural landscapes and traditional, declining practices of interspecies interactions and resource management (for example, Millingerwaard in the Netherlands and Knepp in the UK). The benefits of such projects to the biodiversity of traditional grasslands and silvopastoral systems can be considerable (Mandema et al., 2014; Navarro and Pereira, 2012; Pykälä, 2003; Wieren, 1995) and may closely align with the value systems of pastoralist cultures (Ladle et al., 2011). By contrast, the exclusion of traditional rural activities from rewilded areas, as favored by organizations such as Rewilding Europe, can also be seen as a social experiment in undoing the traditional conception of cultural landscapes (Höchtl et al., 2005; Plieninger et al., 2006; Bauer et al., 2009; Linnel et al., 2015; Rotherham, 2015).

In many parts of South America, European colonization contributed to cultural models of human-free wildernesses to be either exploited or preserved by the governing classes (Sluyter, 2001; Otero, 2006; Hufty, 2012; Root-Bernstein, 2014). The exclusion of humans from rewilded areas under these conditions might therefore be supported by some members of society, while being seen as a collusion with, or repetition of, colonialism by others. In other areas, especially Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and parts of Brazil, indigenous peoples have, to a greater extent, retained their land rights, traditional relations to the land, cosmologies, etc. Consequently, in these areas different cultural schema will govern the perceptions of, and social interactions with, places and species (de la Cadena, 2010). For example, many indigenous cosmologies of the Amazon do not recognise a dichotomy of “cultural humankind” and “natural wilderness” (Descola, 2015). Rather, their cosmology is built around reciprocal shifts in perspective across species, with each species’ perspective taking the position of a person and thus experiencing their reality in a similar way, even while seeing others as experiencing it differently (Viveiros de Castro, 1996; Kohn, 2013; Descola, 2015). This understanding of the world is experienced and mobilized in ways just as real, profound, subtle, and complicated as the Christian heritage that influences European ideas about nature in the image of paradise. In short, choice of cultural schema will strongly influence the frequency and quality of interactions between humans, landscapes and other animals, with profound implications for project management, sustainability, and ecological outcomes. There is no one-size-fits all answer to which landscapes should be rewilded, but the choice should take into account social engagements with landscapes and how rewilding might alter them.

Question 2: How can society deal with monsters? The use of the term ‘monsters’ with reference to rewilding comes from human geography (Lorimer and Driessen, 2013), and refers to uncategorizable and liminal beings that unsettle and threaten elements of civilization, demanding counteractions on the part of civilization. Rewilding can create ‘policy and governance monsters’ by challenging legal, management and cultural categorizations and frameworks for species and lands. For example, “de-domesticated” or feral livestock that managers wish to introduce into passive management schemes can create serious complications within agricultural policy (Lorimer and Driessen, 2013). In contrast, active management of feral horse populations by culling (a policy tool applied to wildlife) is often strongly opposed by groups who do not see them as wild animals (Gamborg et al., 2010). Reintroduced species can also create problems by having different effects in different contexts that policy is not prepared to distinguish between, complicating their regulation. For instance, the feral hog (Sus scrofa) in the Pantanal provide important ecological services and may reduce hunting of native wildlife (Desbiez et al., 2011; Donatti et al., 2011). However, in recently invaded ecosystems, such as the Atlantic and Araucaria forest, this same species may be a disaster (Pedrosa et al., 2015).

Rewilding may similarly blur the lines between native and non-native species through the introduction of surrogate species to replace extinct ones (Griffiths et al., 2010), between protected areas and wildlife parks, between new ecosystems and past ones, and between the wild and the managed. Policy and governance monsters arise where existing frames do not accommodate the visions of stakeholders and managers. This means that rewilding needs to be attentive to the policy frameworks within which it seeks to function, and in the most forward-thinking cases policy and governance monsters could even be positioned as tools for policy reform.

For example, two elements of Chilean law complicate rewilding. While horses and other livestock can be kept with no inspection or special requirements, native wild animals inside a fenced area need to be maintained according to standards of feeding, shelter and care, and are subject to audit. This means that letting animals behave naturally in natural habitats is technically not permitted within fenced areas, thus restricting the ability of researchers to control the conditions of rewilding and monitor change within a discrete (fenced) rewilded area. It also raises the question of how to manage or avoid human-wildlife conflict without using fences. A second issue concerns private protected area legislation, in the form of a new “conservation easements” law that does not automatically provide monetary incentives or material and technical support for conservation. This means that funding to carry out rewilding projects (e.g. purchasing animals, fencing, feed and veterinary care if required, tracking and monitoring equipment and man-hours) or any other kind of conservation or restoration action, is completely dependent on private money, compensation schemes or competitive funding mechanisms. In most cases where conservation easements lack funding and capacity, passive management without reintroductions is likely to be preferred, raising the spectre of “private paper parks.” Possible solutions include using the cultural symbolism of animals such as guanacos (Lama guanicoe) (Lindon and Root-Bernstein, 2015) to leverage government buy-in for suitable management plans and new funding mechanisms.

Question 3: Is there a rationale for non-analogue rewilding? Embracing new rewilding initiatives in all their diversity would inevitably encourage bolder experimentation and a wider array of surrogate species with different levels of historical justification. Indeed, some of the fiercest critiques (Caro and Sherman, 2009; Caro, 2007) of Donlan's extravagant vision of Pleistocene rewilding of the American prairies, replete with elephants and cheetahs (Donlan et al., 2006; Donlan, 2005), were focused on the ecological disparities between the historical fauna and their modern analogues. However, there are also arguments for looser interpretations of historical baselines (Corlett, 2016). First, as a consequence of invasive species and climate change most ecological communities are already historically unique and are likely to deviate further from Pleistocene baselines as the century progresses (Walther, 2010; Ribeiro et al., 2015). Second, ex situ conservation could be a valuable conservation strategy if carefully managed (Bradshaw et al., 2006), and the risks associated with managing large animals in fenced areas are not comparable to those of unplanned species invasions (Corlett, 2016). Finally, the idea that “non-analogue” refers to non-analogous species assemblages rather than non-analogous ecosystem functions seems arbitrarily compositionalist. Ongoing research may provide ways to determine the degree of similarity between ecosystem functions in order to design appropriate plans for taxon substitution (Zamora, 2000; Chalcraft and Resetarits, 2003; Fan et al., 2012; Searcy et al., 2016). At this point, there is no general answer to what suite of traits are most relevant to assess, and this remains a contextual question depending on the target species, the existing community, the restoration functions sought, the climate, and the life history adaptability of the target species.

Throughout South America, but especially in tropical and sub-tropical regions, the loss of Pleistocene and early Holocene megafauna ecosystem processes can be observed in “megafaunal fruits”, which are too large to be eaten whole by remaining dispersers and consequently experience altered and reduced dispersal patterns (Guimarães et al., 2008). Two extinct megafaunal candidates for large fruit dispersal in South America are the gomphothere (Cuverionus/Notiomastodon) and the giant sloths. Though highly controversial, the introduction of a functional analogue such as elephants (Elaphas maximus or Loxodonta africana) to South American forests with megafaunal fruits might restore tree regeneration patterns (e.g. Galetti, 2004; Blake et al., 2009; Haddad et al., 2009; Omeja et al., 2014; Asner et al., 2016), along with other ecological functions presumably also associated with gomphotheres, giant sloths, and perhaps other herbivorous megafauna (Galetti et al. in review). An exciting opportunity to test the role of elephants as megafauna surrogates in South America is a recently established sanctuary for elephants in Brazil, where 1100ha of savanna will be designated for the well-being of formerly captive elephants (globalelephants.org). Although this is not a rewilding project, scientists could learn at small scale the ecological effect of a large mammal in a South American savanna.

There is also an argument that non-analogue rewilding “experiments” have already taken place in the form of accidental reintroductions (Fig. 2). The “reintroduction” of horses to the Americas by European colonists is a prime example (Naundrup and Svenning, 2015). Wild horses occur in many South American landscapes, but there is little or no ecological information about their effects on the ecosystem (Janzen, 1981, 1982). The original Pleistocene horse species in South America were much smaller: a better analogue might be ponies. Equally, escaped populations, such as the hippopotamus population in Colombia (Valderrama Vasquez, 2012; Monsalve Buriticá, 2014), or water buffalo in Brazil (Lage Bisaggio et al., 2013), raise the question of whether these species recreate some set of extinct Pleistocene ecological functions or are simply invasive.

“Accidentally rewilded” species in South America. Top left, wild boar Sus scrofa (photo © M. Galetti), top right, horses Equus ferus caballus, bottom left, hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius, bottom right, water buffalo Bubalus arnee. These species might have some functional equivalence to extinct megafauna, although this has not generally been assessed.

Question 4: How do we justify baselines? A baseline could be found to correspond to the objectives of almost any rewilding project (Fig. 3). Of course, it can always be argued that past environments are different from, and irrelevant to, present and future environments, making the use of baselines for rewilding a distraction (Gillson et al., 2011). Either way, baselines can be used as a hypothesis-generating scenario for socio-ecological experimentation. They can also be used to create a compelling story around which to generate public support and involvement. Such narratives are important for aligning rewilding projects with local framings and values of nature and landscapes.

For example, a developing rewilding project in Chile (Proyecto REGenera: Restoration of Espinal with Guanacos, Fig. 4), seeks to test whether browsing by reintroduced guanacos (Lama guanicoe) contributes to restoration of the traditional silvopastoral habitat called espinal, a savanna dominated by the South American Acacia caven (Root-Bernstein et al., 2016). Whether espinal existed in central Chile in prehispanic times is unclear, due to biases inherent to the paleoecological and historical records (see Root-Bernstein and Jaksic, 2013). The traditional perspective is that the region was previously covered in dense, closed-canopy endemic sclerophyllous forest, with matorral (shrub) and espinal habitats representing modern degradations. However, part of the justification for this rewilding project is that this closed canopy perspective is wrong, and that the prehispanic baseline was a mosaic of open acacia woodland and closed sclerophyllous forest. Since this new baseline scenario is close to what is currently found in central Chile, it may suggest a continuous legacy of biocultural value (Otero, 2006). By changing perceptions of the cultural value of espinal as a natural and historic landscape, the hope is to motivate restoration and conservation actions (Lindon and Root-Bernstein, 2015), as well as contribute to the development of further ecological research on succession and ecosystem processes in matorral and espinal habitats (e.g. Root-Bernstein et al., 2017; Root-Bernstein and Jaksic, 2015; Hernández et al., 2015, 2016).

Other regions in South America also have unclear paleoecological histories, in which the role of humans in shaping past and present ecologies is disputed. The existence of terra preta throughout the Amazonian basin clearly demonstrates that the rainforest was never “empty” (Posey, 1985; Glaser, 2007), although the density of human settlements over time is disputed (Barlow et al., 2012). There are probably many ecosystems or “biomes” in South America that currently lack megafauna and also have long histories of land use by indigenous communities (e.g. Buritizais, Castanhais, “Campos sulinos” or grasslands) (Fernandes-Pinto and Saraiva, 2006; Overbeck et al., 2007; Almeida, 2008). The whole “cerrado” region seems to be a mosaic of formations that does not comfortably fit into a unique classification as a “biome” (Batalha, 2011). In such areas, following any particular baseline necessarily requires adopting a particular interpretation of ambiguous data about the history of anthropogenic influences. Baselines for rewilding should thus be chosen strategically to enrol certain stakeholders, facilitate particular actions, and generate productive dialogues.

Question 5: Is it possible to do rewilding with small species? Rewilding is commonly thought of as dealing with megafauna. The largest megafauna are likely to have important ecological impacts disproportionate to their biomass (Owen-Smith, 1992) and are thus potentially efficient restoration tools. They are, moreover, disproportionately missing from ecosystems (Galetti et al., 2017). The reintroduction of megafauna has some advantages (e.g. protecting and locating individuals, lesser probability of becoming invasive, outcome visibility to public), but also significant disadvantages (e.g. handling, attraction to poachers, human-wildlife conflict) (Corlett, 2016). Megafauna are usually charismatic, and the Pleistocene and Holocene megafaunal extinctions fascinate both scientists and the public (Martin and Klein, 1989; Barnosky et al., 2004). Bringing back megafauna can thus have a strong symbolic role in creating ‘wild’ landscapes (see Lindon and Root-Bernstein, 2015). Nevertheless, under some ecological and social circumstances, small animals could be effective restoration tools. For example, many ecosystem engineers are relatively small animals (Root-Bernstein and Ebensperger, 2012). Key functions missing from the Atlantic forest of Brazil are mostly carried out by medium-sized species, such as pacas (Agouti paca), Howler monkeys (Alouatta spp.), sloths (Bradypus spp.), agoutis (Dasyprocta spp.), tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), collared peccaries (Pecari tajacu), ocelots (Leopardus pardalis), tortoises (Chelonoidis carbonarius) and toucans (Ramphastidae spp.) (Jorge et al., 2013; Cid et al., 2014; Galetti et al., 2017; Kenup et al., 2017; Sobral et al. this issue). Thus, in the South American context, small and medium sized animals may be appropriate for rewilding under different scenarios: loss of an ecosystem engineer after habitat loss or persecution, or general trophic downsizing (Young et al., 2016) or in highly fragmented forests (Sobral et al., this issue). Finally, it is important to note that body size is relative: what it means to be megafaunal on islands is relative to the size of the island (Hansen and Galetti, 2009). A similar logic might hold for geographically isolated areas of endemism such as Chile, which is strikingly poor in large and medium sized species.

Question 6: What is the right scale for a rewilding project? There are several arguments for rewilding large areas: as for any protected area, larger areas will have fewer edge effects and can support more viable populations of both large and small species (Triantis and Bhagwat, 2011). In most places outside Europe, the urgency to conserve large areas reflects the recognition that some places can still be protected before large-scale anthropogenic fragmentation and habitat conversion takes place. In Europe, larger spaces have recently become available for conservation due to agricultural land abandonment (Navarro and Pereira, 2012). However, beyond practical issues of land availability, the amount of land required for rewilding depends on the species being used, the scale of the ecological restoration outcomes desired, and local conceptions of wilderness (Corlett, 2016).

A gap in the ecological literature relevant to this issue is the scaling of ecosystem processes; while we can assess perceptions of wildness or species’ habitat requirements at any scale of interest, ecosystem processes are typically measured or estimated at regional or even global scales (e.g. Doughty et al., 2016). At smaller scales, such as landholdings, ecosystem processes are strongly dependent on landscape heterogeneity, edge effects, species presence or absence (i.e. within their range) and species movement patterns (e.g. Root-Bernstein et al., 2013). At the same time, all spatial scales are affected by uncontrollable factors such as regional and continental deforestation affecting weather patterns (Medvigny et al., 2011) or economic policies (i.e. “teleconnections” Richards et al., 2012; Le Polain de Waroux et al., 2016; Nolte et al., 2017). Because of these long-distance connections, there is no typical scale at which all the main factors (inputs) affecting the ecosystem processes (outputs) are contained within the same area. Further, measures of the necessary density and extent of functions to yield different process outcomes are not well established. Alternatively, recent work in Tijuca National Park in Brazil has looked at the time to establish a full range of ecological interactions after species introduction (Genes et al., 2017). This approach should be extended to looking at the scaling-up across space of ecological impacts of species reintroductions.

Question 7: Should rewilding projects worry about sample size and pseudo-replication? As rewilding projects increase in frequency and attract academic interest, there will inevitably be calls for more experiment-quality conditions for data gathering and analysis. A significant issue here is likely to be sample sizes and independence of data points. Imagine a scenario in which a 1000ha of cerrado hosting a family group of three introduced elephants is compared to a similar sized reference area without elephants. The unit of response being measured after reintroduction is the germination rate of seeds after endozoochory on a per-plot basis. Is the correct sample size 1 (1 experimental site) or is it the number of sampling plots? In other words, does the treatment consist of the presence of elephants, or the quantifiable interactions between elephants and their environment within sample plots? Because the family group and the site are small, some aspects of the ecology of the species could be affected, and so this scenario may be criticized for not replicating valid “wild” conditions. These kinds of issues are not unique to rewilding, and at times have been considered deeply problematic for ecology as a whole (Hurlbert, 1984).

Restoration ecologists and community ecologists often take different approaches to these issues. Restoration interventions typically measure effects at multiple sub-sites or samples within restored and reference areas, with the sample size derived from the number of sub-sites or samples. Community ecologists tend to apply discrete treatments the size of each independent sample, e.g. multiple exclusion areas. These differences in approach may produce controversies at the boundaries between the two fields, which are likely to slow academic study of ecological aspects of rewilding.

In addition, one could consider analyzing a rewilding project as a case study, a distinct genre of analysis found in some social and applied sciences, in which analysis of a single site or project is legitimate. Case studies are particularly amenable to including social data, and can integrate a qualitative as well as quantitative mode of analysis.

South American ecologists have strong traditions in community ecology and botany, in particular. Restoration ecology as an academic field appears to be underrepresented. For example, just 4% of 468 papers on reforestation from Restoration Ecology were from South America (Ruiz-Jaen and Aide, 2005). However, international publications on restoration ecology coming from Argentina and Colombia, at least, are growing (Rovere, 2015; Murcia and Guariguata, 2014). Restoration as a conservation practice, for example in former industrial sites, is not always well-regulated or monitored. South American rewilding scientists have the opportunity to develop their own approaches to data gathering and scientific inference at single-site projects, perhaps in collaboration with the strong botanical and community ecology traditions.

Question 8: When should we rewild carnivores? The reintroduction of large carnivores or the expansion of their populations and ranges back to a historical baseline is the goal of many rewilding programs. While top carnivores rarely have direct habitat restoration effects, they may change how existing herbivores affect plant communities through trophic cascades and ‘landscapes of fear’ (Laundré et al., 2001). The absence of top predators from landscapes often means that active management of herbivore populations remains necessary, or that large herbivore populations self-regulate through starvation (Mduma et al., 1999; Fritz, 1997). Both culling and starvation can be undesirable from management and public relations standpoints. At the same time, the reintroduction of large carnivores can prompt fear of human-wildlife conflict, as well as actual conflict (Dickman, 2010; Treves and Karanth, 2003). Large herbivores can also be dangerous to humans: deer, for example, cause about half of all wildlife-caused human fatalities in the United States annually, four orders of magnitude greater than puma fatalities (Conover et al., 1995). Managing megafauna-associated risks can draw on both traditional practices as well as advances in design for human-wildlife coexistence (King et al., 2009; Treves and Karanth, 2003). Some authors have called for a rewilding of the experience of being in nature, which might be achieved in part by bringing back a sense of fear and awe in the face of large, unpredictable species (Monbiot, 2013). Although this may resonate with some stakeholders, in practice the deliberate introduction of predators may conflict not only with the livelihoods of rural people, but also with numerous economic structures that depend on the mitigation and management of risks, such as investment, insurance and commodity prices.

The (re)introduction of prey species may also have the unintended consequence of increasing existing predator populations (e.g. Verdade et al., 2016). Human-wildlife conflicts can also occur when prey are abundant and predators are not reintroduced, e.g. the conflict between protected guanacos (Lama guanicoe) and ranchers in Southern Chile (Hernández et al., 2017). Bottom-up as well as top-down effects need to be considered.

The reintroduction of ocelot and margay (Leopardus spp.) has been proposed in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil (Galetti et al., 2017), and jaguar (Panthera onca) are being reintroduced into Iberá Natural Park in Argentina (Caruso and Jiménez Pérez, 2013). In the Corrientes province where Iberá is located, the jaguar is associated with cultural pride and the reintroduction is not expected to provoke conflict despite the presence of cattle ranching (Caruso and Jiménez Pérez, 2013). By contrast, in Chile both large and small felids are associated with negative beliefs and are persecuted (Herrmann et al., 2013; Zorondo-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Ohrens et al., 2016), making their reintroduction to parts of their historical range that are currently unoccupied unlikely. However, despite or because of a very low density of guiña (Leopardus guiña) on Chiloe Island, Chile, local people have positive attitudes towards the species (Díaz, 2005). Human-wildlife conflict involving felid predators is common throughout South America (e.g. Michalski et al., 2006; Cavalcanti et al., 2010). The incidence of conflict may also to be linked to the expansion of agricultural frontiers (soy, oil palm and cattle ranching), such that farmers and wild felids are constantly brought into contact. This situation may change and new opportunities for rewilding may arise as agricultural frontiers are stabilized or land is abandoned.

Question 9: Do we need to distinguish rewilding from safari parks and zoos? The idea that rewilding simply creates large zoos or safari parks has been used to criticize Pleistocene rewilding (Caro, 2007). Critics see such reintroductions as unnatural, requiring excessive management and primarily serving an entertainment function. However, zoos can play useful roles, such as ex situ conservation, environmental education for the public, and raising funds for in situ conservation elsewhere. Safari park-like rewilding projects could have similar benefits. Pleistocene rewilding is unlikely to distract the main conservation NGOs from their core missions, but may attract new actors, mainly at local and regional scales (e.g. Table 1).

The related argument that rewilded American and European sites will capture the megafaunal tourism and charity market to the detriment of in situ conservation (Rubenstein et al., 2006) may be overly simplistic. We predict that a visit to Payne's Prairie to see bison in Florida is likely to be perceived as different from seeing bison in Yellowstone National Park or Bialoweiza Forest in Poland. Similarly, visits to Whipsnade (UK) and the San Diego Wildlife Park (US) are not comparable to a visit to Kruger National Park in South Africa. Place matters to wildlife perceptions (e.g. Montag et al., 2005; Lindon and Root-Bernstein, 2015). By the same token, South American rewilding projects and protected areas should not fear competition for nature tourism from rewilding on other continents.

However, the extant South American mammal fauna is composed mostly by medium and small animals (e.g. peccaries, agoutis, monkeys). Within South America, the large African mammals are usually preferred as public attractions in zoos and safari parks. In some countries, such as Chile, the public is more familiar with African, European and North American charismatic species than with native and endemic ones (Root-Bernstein and Armesto, 2013; Root-Bernstein, 2014). The creation of safari-like projects in South America with large non-native mammals might confuse the educational purpose of zoos. There is an educational value to observing “exotic” animals (and plants), which can teach the public about the variety and diversity of species in the world. But South American zoos and other conservation programs should also be supported in initiatives to make small and medium-sized native species, not just exotic ones, visible and known. If rewilding projects use proxy megafauna to restore lost ecosystem functions, they need to make an extra effort towards educating the public about the South American megafauna, both before and after the late Pleistocene/early Holocene megafaunal extinctions, that the surrogates represent. It would be unfortunate, and perhaps profoundly damaging to the public understanding of science and socio-ecological relations, if the South American public saw only elephants, hippos and horses as “the animals”.

Question 10: What should be included in integrated monitoring and assessment?

The most basic requirements for a rewilding project, monitoring of the (re-)introduced species population and its ecological impacts, can be challenging, requiring technical and funding resources that many projects lack. To date, the best-monitored species reintroduction in South America may be that of the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) (Kierulff et al., 2012). Reintroduced agoutis in the Atlantic Forest have also been well-monitored (Kenup et al., 2017).

Many reintroduction programs and habitat restoration programs could contribute to knowledge about socio-ecological system dynamics with the addition of some monitoring and assessment of additional ecological and social data. Monitoring of rewilding projects should be designed to detect both predicted and surprising outcomes, as shown by the example of Oostvardersplassen, where the reintroduction of large herbivores led to increases in many bird populations through a number of mechanisms (e.g. Mandema et al., 2014; Vera, 2000). Monitoring of rewilding outcomes via citizen science participation can also be a way to engage the public in a controlled way in programs whether or not significant human interaction with the landscape is desired (Devictor et al., 2010).

Conservationists have learned since the 1980s that working with local stakeholders is fairer and more effective than excluding and ignoring them (Hulme and Murphree, 1999; Sarkar and Montoya, 2011; Reid et al., 2016). One of the problematic elements of some rewilding approaches is a return to the fortress conservation mentality. We argue that a key element distinguishing reintroductions from rewilding projects is the level of cultural interest of the project for local and broader publics. Not only will rewilding affect human relations to the landscape in physical ways (i.e. changes in human-wildlife conflict, changes in habitat structure), but in psychological and cultural ways (Lindon and Root-Bernstein, 2015; Monbiot, 2013). A complete monitoring and assessment regime that maximizes learning opportunities should thus include a range of socio-economic, ethnographic and psychological variables.

A case in point is Proyecto Iberá of the Conservation Land Trust, in Argentina. The project itself does not always use the term rewilding to describe its work, but it has key features in common with rewilding. The project has begun to reintroduce giant anteaters and plans to reintroduce pampas deer, green-winged macaws, peccaries, tapirs and jaguars (www.cltargentina.org accessed 2016; Zamboni et al. this issue). In addition, the project highlights the cultural identity of the region and runs environmental education aimed towards a future ecotourism economy, and a conservation training centre to produce local conservation professionals. Nevertheless, although the project was initiated in the 1980s, to our knowledge there is only one publically available publication providing assessments or analysis of the site and its reintroduction plans from a socio-ecological, biocultural, ethnographic, or sociological perspective. A paper on attitudes towards jaguars pre-reintroduction provides an interesting baseline (Caruso and Jiménez Pérez, 2013) which one hopes will be followed up. A more complete, and published, account of both social and ecological aspects of the site would provide opportunities for comparative critical assessment and learning.

South American rewilding sites have an opportunity to set themselves up as matched comparison sites to similar projects in other ecosystems. Monitoring should thus focus on both key similarities between the sites (e.g. similar restored ecosystem functions) and key differences (e.g. plant diversity).

Realistically, integrated monitoring requires a generous budget that will not disappear after a few years. Surprising or significant effects of rewilding may only emerge on a decadal scale (see above). Potential rewilding projects are thus faced with pragmatic trade-offs between doing what they know they can afford in the long-term (potentially nothing) and investing an enormous effort in securing research or conservation funding from governmental and NGO funding schemes every few years. Emerging carbon markets and carbon emission compensation schemes might become sources of funding, while also, probably, having low reporting standards that will not unduly burden project management. Brazil has a program supporting long-term ecological monitoring (PELD) in 30 sites, although to our knowledge none of these sites has rewilding projects (http://cnpq.br/apresentacao-peld). The ILTER (International Long Term Socio-Ecological Research) network lists sites in Brazil, Venezuela, Costa Rica and Chile, but the network does not benefit from a dedicated international funding source. It is clear that without reliable funding options, not only will rewilding projects be hard to start, they will be difficult to justify, assess, and learn from.

ConclusionsSouth American ecosystems face particular conservation challenges due to a wide variety of biodiverse habitats and endemic species, various colonial histories, underdevelopment, the expansion of agricultural frontiers, climate change, and weaknesses in their environmental policies. Rewilding (with native or non-native species) is not in the environmental agenda in South America but could provide an important tool for the conservation of areas that have rapid habitat loss such as the Brazilian cerrado. Reintroductions are already taking place in some countries in South America, but many are not targeting the ecological function played by extinct species. At least one element that we argue that rewilding can bring to conservation in the region is a more explicit attention to the social changes that may result from species reintroductions: even if the extinctions and extirpations being “reversed” are recent, the socio-ecological system will not simply be brought back to an earlier state by the species reintroduction. Rewilding contributes to socio-ecological transformation. Researchers should take the opportunity to understand the effects of unintended rewilding such as horses, feral hog, buffalo and even hippopotamus on South American ecosystems. As we have tried to emphasize in this paper, there are numerous ways to think about what rewilding is and how it should be done, and we do not believe that there are prescriptive recommendations or general optimal approaches that all South American rewilding projects should follow. We hope that South American rewilding projects will answer the questions posed here in novel and contextually relevant ways.

We are indebted to Paul Jepson, Adrien Lindon, Benji Barca, Frans Vera, Jennifer Gooden and Alison Boyes for conversations that contributed to our thinking. MR-B was funded by FONDECYT (No. 3130336), Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene (AURA), a Danish National Research Foundation Niels Bohr professorship project, and a Marie Curie FP7 COFUND Agreenskills Fellowship during the preparation of the paper. RJL is funded by CNPQ (grant number 311412/2011-4). MG is funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPES) and CNPq.