The extinction of frugivores has been considered one of the main drivers of the disruption of important ecological processes, such as seed dispersal. Many defaunated forests are too small to restore function by reintroducing large frugivores, such as tapirs or Ateline monkeys, and the long-term fate of large-seeded plants in these areas is uncertain. However, such small fragments still host many species and play relevant ecosystem services. Here, we explore the use of two tortoise species, the red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius) and the yellow-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis denticulatus), as ecological substitutes for locally extinct large seed dispersers in small forest patches in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. We employed prior knowledge on the known occurrences of Chelonoidis species and used ecological niche modeling (ENM) to identify forest patches for tortoise rewilding. Based on habitat suitability, food availability and conservation co-benefits, we further refined our analysis and identified that the more suitable areas for tortoise reintroduction are forest patches of northern Atlantic Forest, areas with high defaunation intensity. Giant tortoises have been used to restore lost ecological services in island ecosystems. We argue that reintroducing relatively smaller tortoises is an easy-to-use/control conservation measure that could be employed to partially substitute the seed dispersal services of extinct large disperser species, mitigating the negative cascading effects of defaunation on reducing plant diversity.

Tropical ecosystems are facing fast deforestation and defaunation rates (Dirzo et al., 2014). For instance, large tracts of forests and savannas in Brazil are being converted into agricultural and pasture lands, thereby threatening many wild populations and endemic species (Laurance et al., 2014). Fragmentation leaves behind an archipelago of small patches that can hardly sustain viable populations of large-bodied forest-dwelling species (Turner, 1996). The extinction of large vertebrates can trigger cascading effects of important ecosystem services such as carbon storage (Bello et al., 2015). Because many forest patches are deemed too small to maintain relatively high levels of biodiversity in the long term, the value of these areas for conservation has mostly been neglected (Laurance et al., 1997). However, even though such forest patches cannot harbor large vertebrates, they contain important components of biodiversity, particularly tree species (Tabarelli et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2007; Farah et al., 2017). Consequently, the long-term fate of the populations of plants that rely on large seed dispersers is uncertain (Cordeiro and Howe, 2003; Galetti et al., 2013).

Rewilding—introducing ecologically similar species to perform ecosystem functions analogous to those of extinct species—is being increasingly used in both temperate and tropical ecosystems as a strategy to restore functionality in heavily degraded ecosystems (Svenning et al., 2016). A notable example of a highly fragmented environment that could benefit from rewilding programs is the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, which although figuring as a biodiversity hotspot, has been under great overexploitation and intense urbanization since Brazil's colonization (Ribeiro et al., 2009). Given that a significant part of Atlantic Forest remnants does not support large-sized species (Morcatty et al., 2013), small/medium-sized species, once efficient dispersers, present the best alternative to restore and maintain the biome's ecological functions.

Tortoises (Family Testudinidae) have been used to restore seed dispersal and herbivory functions in island ecosystems due to their generalist diet and fruit-based preferences and their capacity of ingesting large quantities of relatively large fruits and seeds (Hansen et al., 2010, 2008; Griffiths et al., 2011). Moreover, there is mounting evidence that tortoises are important seed dispersers and can disperse large-seeded plants in their natural ecosystems (Strong and Fragoso, 2006; Jerozolimski et al., 2009). The current absence of tortoise in several Atlantic Forest remnants is probably consequence of the historical hunting combined to fast landscape conversion (Wang et al., 2011). Tortoises are still highly appreciated as food and for pet purposes in the Amazon (Morcatty and Valsecchi, 2015a,b), but there are no recent records of intense hunting of tortoises in Atlantic Forest remnants.

Here, we explore the use of two tortoise species, the red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius), and the yellow-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis denticulatus), as ecological analogs for large seed dispersers in small remnants of Brazilian Atlantic Forests that cannot support large frugivores. We employed prior knowledge on the known occurrences, and habitat preferences of both Chelonoidis species, forest food availability and ecological niche modeling to calculate a feasibility index and propose sites for tortoise rewilding.

Methods and study siteThe Atlantic Forest (AF) of South America was once one of the largest tropical and subtropical forests in the world, originally covering around 150 million hectares along the Brazilian coast and part of Paraguay and Argentina (Ribeiro et al., 2009). Currently, 100 million people live in the AF domain and the anthropogenic impacts have transformed its natural landscape and strongly decreased its biodiversity (Laurance et al., 2009). The industrialization and agricultural expansion are considered to be the main causes of AF landscape fragmentation (Scarano and Ceotto, 2015). Currently, the AF covers <12% of its original area, mostly comprising fragmented and disconnected patches of <50ha (Ribeiro et al., 2009). Nonetheless, the remaining AF hosts a larger number of endemic species and is considered one of the five major hotspots for conservation in the world (Myers et al., 2000; Visconti et al., 2011).

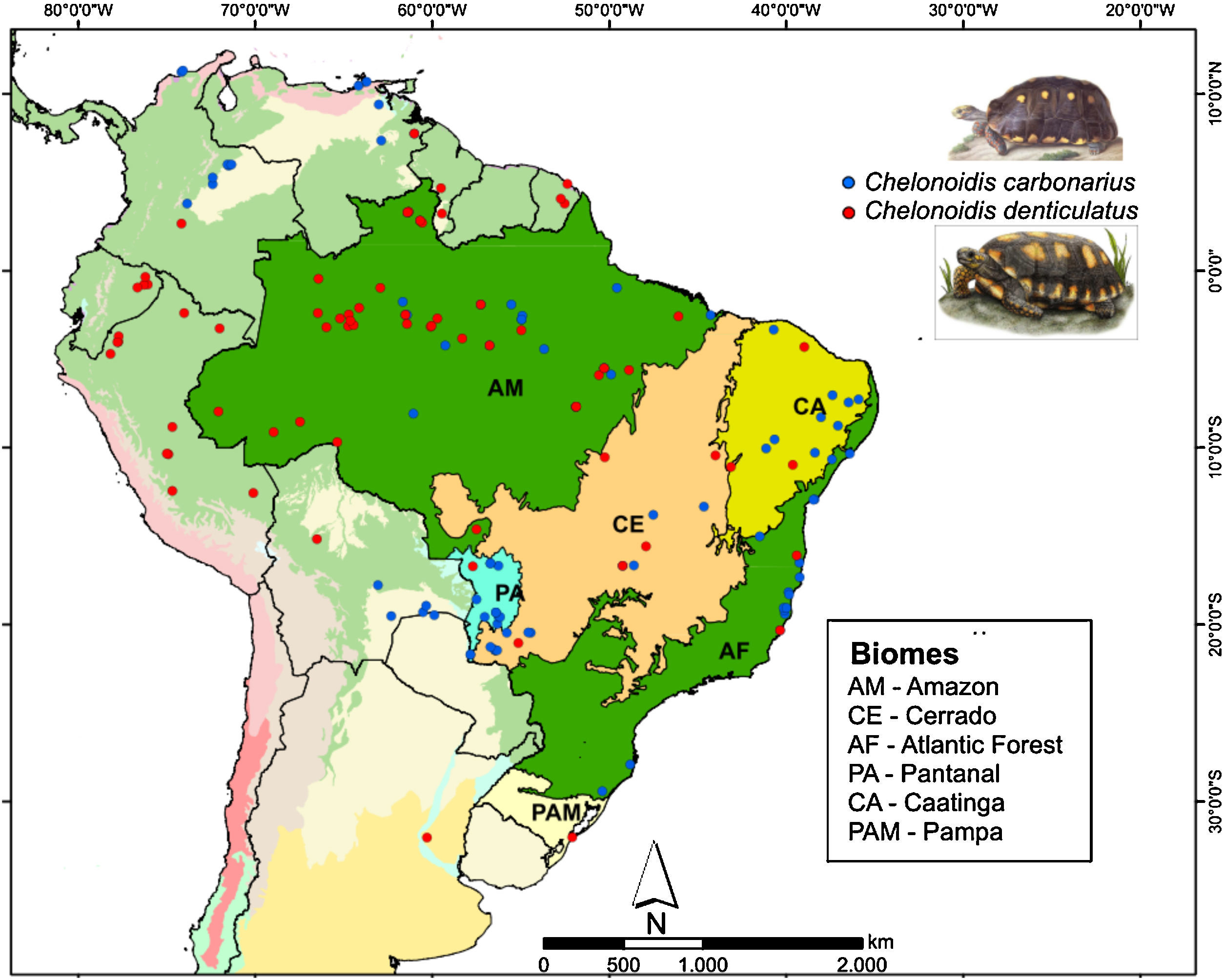

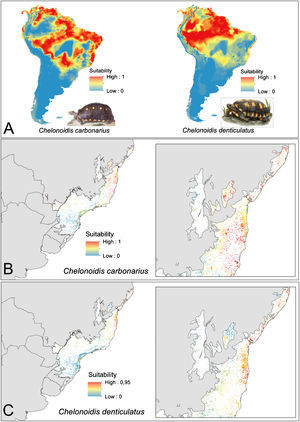

Two species of tortoise occur in the AF, the red-footed toirtose (C. carbonarius) and the yellow-footed tortoise (C. denticulatus) (Fig. 1). Tortoises are popular hunting targets since they can be easily captured and kept alive for a long time. Thus, they have probably been used as food by humans for millennia. These species are known to rapidly disappear in overhunted areas (Peres and Nascimento, 2006), and it is likely that many tortoise populations went extinct in the AF after the Europeans arrived and occupied the Brazilian coast (Dean, 1996). Today, the conservation status of both tortoise species should be considered as critical in the AF, although many populations of both species still occur in the Amazon and the Cerrado (Fig. 1).

Ecological niche model (ENM) estimates associations between environmental variables and known species occurrences to infer the conditions under which the populations of a species can survive and then plot suitability values in areas where the species’ occurrence is unknown (Franklin, 2009; Peterson et al., 2011).

We collected information on the occurrence of C. carbonarius and C. denticulatus in South America using four different methods: personal observations, online databases (GBIF – Global Biodiversity Information Facility; MCZBASE – The Database of the Zoological Collections, and records in iNaturalist and VertNet), news websites, thesis, academic papers, and management plans for protected areas. We only used information that contained locality or geographic positions, the observer name and the date (month or year) of the records. In total, we found 76 and 94 occurrence points for C. denticulatus and C. carbonarius, respectively (Fig. 1). After the search, we filtered these points to obtain a unique occurrence in each cell, using a grid of cells with 2.5 arc-minutes resolution (∼4.5km×4.5km at the Equator). We used this cell size because all climate layers used in our study were available in this resolution and embraced all known occurrence points of these tortoise species.

We used the entire South American continent as a background for our modeling because we considered this region as being open/available to dispersal for our two studies in historical time and all known occurrence points are in this area, two crucial criteria for background selection (Barve et al., 2011). To characterize the environmental aspects of the background region, we downloaded all 19 bioclimatic variables available in the WorldClim database (www.worldclim.org; Hijmans et al., 2005). These variables are derived from temperature and precipitation data, and are thus likely to be correlated among them. To decrease the correlation rate, we performed a factorial analysis on the 19 the bioclimatic variables to select variables with low multicollinearity, using Varimax rotation (similar to the method used by Sobral-Souza et al., 2015). In the end, five variables remained: Annual Mean Temperature, Mean Diurnal Range, Isothermality, Precipitation of Wettest Quarter and Precipitation of Driest Quarter, which together explained 92% of background climate variation within our 2.5 arc-minutes cell size.

Currently, there are many different algorithms available to predict species distribution and the combined use of several of these algorithms is generally thought to increase the reliability of models by considering a wide range of distributional patterns (Barry and Elith, 2006; Araújo and New, 2007; Diniz-Filho et al., 2009). In this sense, we used five algorithms based on different modeling methods. The first three were presence-only methods: envelope score – Bioclim (Nix, 1986), and two distance methods – Mahalanobis Distance (Farber and Kadmon, 2003) and Domain (Gower distance; Carpenter et al., 1993). The last two were machine-learning methods based on presence-background records: Support Vector Machines (SVM) (Tax and Duin, 2004) and Maximum Entropy – MaxEnt (Phillips and Dudik, 2008). The algorithms were built in “dismo” and in “kernlab” R-packages (Karatzoglou et al., 2004; Hijmans et al., 2015).

We partitioned the occurrence points into two subsets, 75% and 25% for training and evaluate the models, respectively. As the training and testing points are subsets of the same occurrence points, we randomized the two subsets 20 times to minimize the spatial structure between the training and testing datasets, thus providing less biased evaluations. In this way, we built 20 models with each of the five algorithms, totaling of 100 models (20 times×5 algorithms) for each tortoise species. Based on recommendations by Liu et al. (2013, 2016) about which threshold to use when presence-only data are available in niche modeling analysis, we used the maximum sensitivity and specificity threshold to transform the continuous maps into binary maps. With this threshold we evaluated the models using the True Skill Statistic (TSS) value, which ranges from −1 to 1. Negative or near-to-zero values indicate that predictions are not different from a randomly generated model, whereas predictions with values closer to 1 are considered to be excellent (Allouche et al., 2006).

To predict the final maps, we followed the ensemble forecast proposed by Araújo and New (2007). For this, we concatenated the 20 binary maps belonging to the same algorithm and obtained the final consensus map by computing frequencies from all algorithms. The final map's cell values show the standardized frequencies of predicted presences combining all generated models.

Species consumed by tortoisesWe performed an exhaustive literature review to compile a list of fruit species eaten by C. denticulatus and C. carbonarius. Because there is no study on seed dispersal by tortoise in the Atlantic forest (Bello et al., 2017), we used information from other biomes (Moskovits and Bjorndal, 1990; Strong and Fragoso, 2006; Jerozolimski et al., 2009; Donatti et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011) to assess the role of tortoises as potential dispersers of large seeds. In addition, we included data from experiments performed by two authors of this study (L. Lautenschlager and M. Galetti, unpublished data, 2016), who assessed the potential role of tortoises in forests regeneration by evaluating the seed dispersal of fruits offered to C. carbonarius individuals in captivity.

We also identified the closest relatives in the AF of plant species that are known to be dispersed species by tortoise in other biomes. We then consulted the database from REFLORA (specifically Flora do Brasil, 2020 – Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, 2008), the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2014) and Red List of Brazil's Flora (MMA, 2008) to obtain information on the occurrence and the threat category of these plant species (Table S1).

We also identified the closest relatives in the AF of plant species of that are known to be dispersed species by tortoise in other biomes. We then consulted the database from REFLORA (specifically Flora do Brasil, 2020 – Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, 2008), the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2014) and Red List of Brazil's Flora (MMA, 2008) to obtain information on the occurrence and the threat category of these plant species (Table S1).

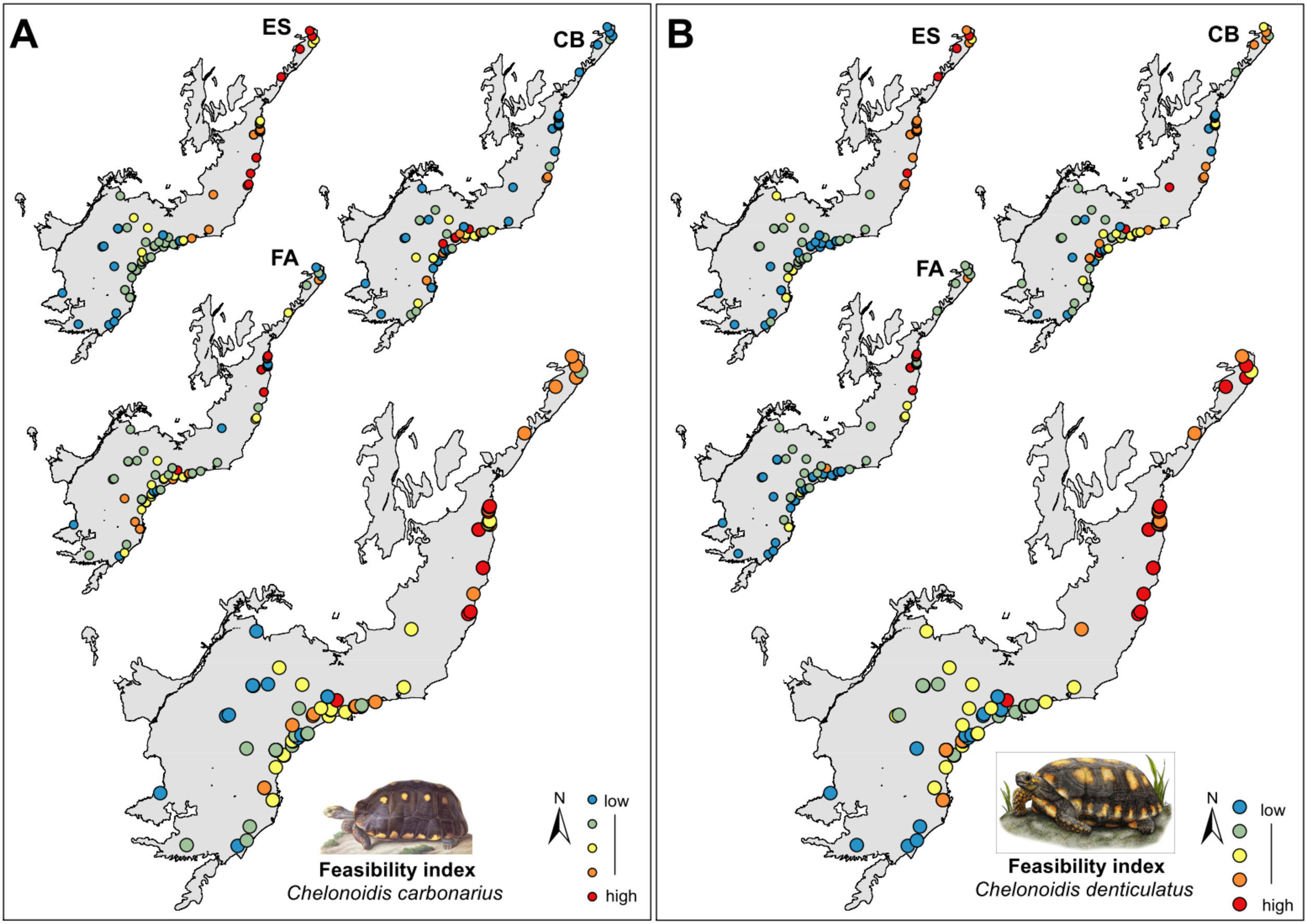

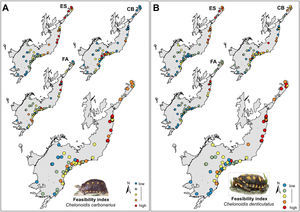

Selection of areas for tortoise rewildingWe modeled and ranked the feasibility of each area for successful reintroduction. The feasibility index was computed by averaging three factors: (i) environmental suitability (ES), (ii) food availability (FA) (density of fruiting trees) and (iii) conservation co-benefits for endangered plant species (CB).

To predict the environmental suitability (ES) of the two Chelonoidis species in the AF, we cropped the suitability values of models generated by ENMs for South America to AF remnants only (Ribeiro et al., 2009). Thus, we obtained the suitability values for each tortoise species in each forest patch.

To assess food availability (FA) for tortoise species, we analyzed 84 forest patches where we had information on tree composition and density (de Lima et al., 2015). Then, we counted the number of phylogenetically closest species potentially consumed by the tortoises and their abundance over one hectare. We standardized the values between 0 and 1 and assigned 0.5 as a weighted value for each component.

To account for the conservation co-benefits (CB), we counted the number of phylogenetically closest species potentially consumed by tortoises that are threatened with extinction and the abundance of those species. We standardized the values between 0 and 1 and assigned 0.5 as a weighted value for each component.

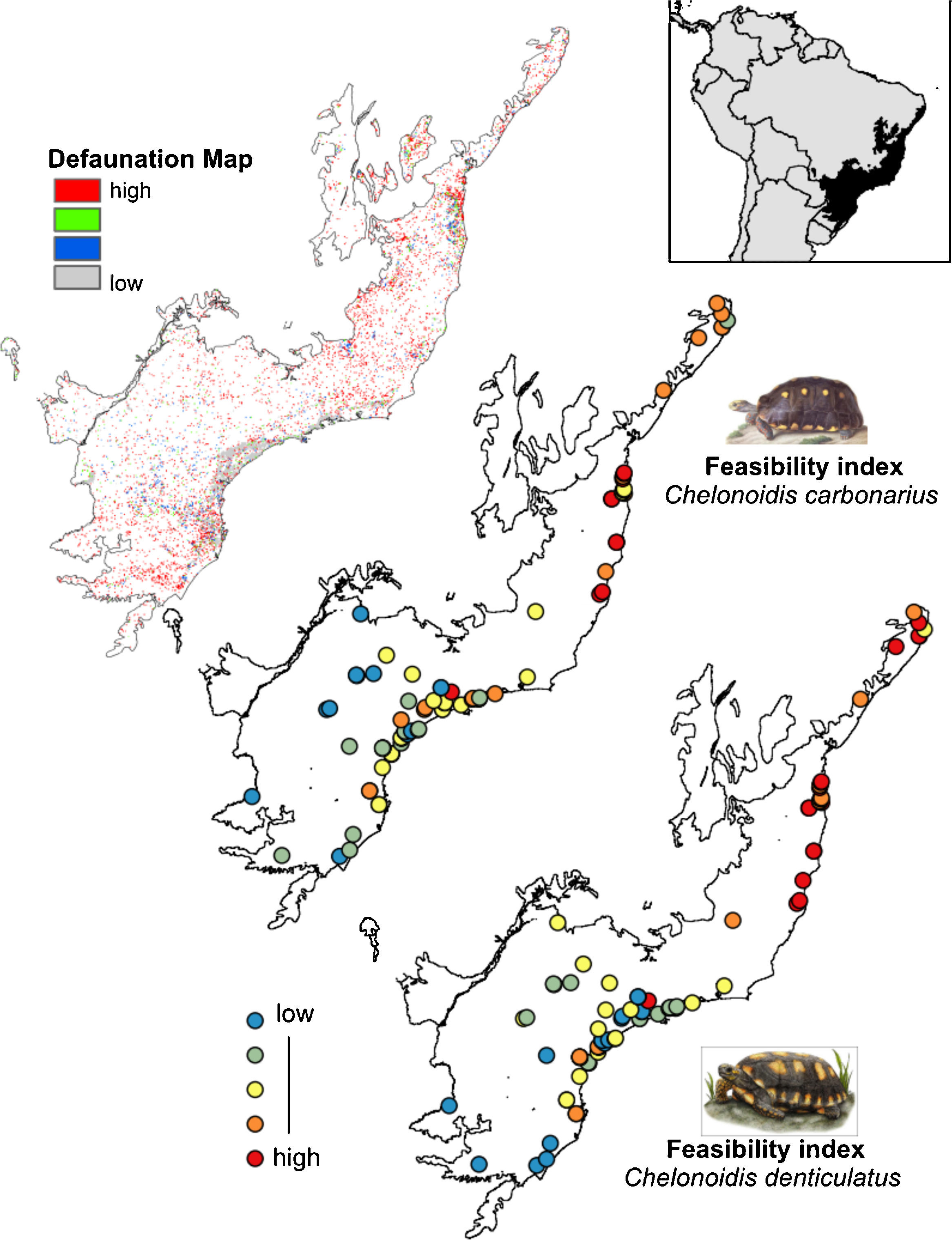

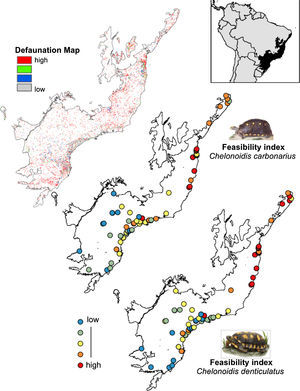

Finally, we calculated the feasibility values for all 84 fragments and compared them with the defaunation map proposed by Jorge et al. (2013). The authors used ENMs approaches to identify the potential distribution of four surrogate mammal species (jaguar, wooly monkey, tapir and white-lipped peccary) in Atlantic Forest remnants to generate a richness map. Areas with higher richness for surrogate mammals were considered less defaunated and areas with lower richness were considered highly defaunated. In these areas the rewilding process is considered priority. We suggest that the resulting selection of forest patches have the greatest likelihood to maximize the functional resurrection of ecological functions that could be provided by the two tortoise species.

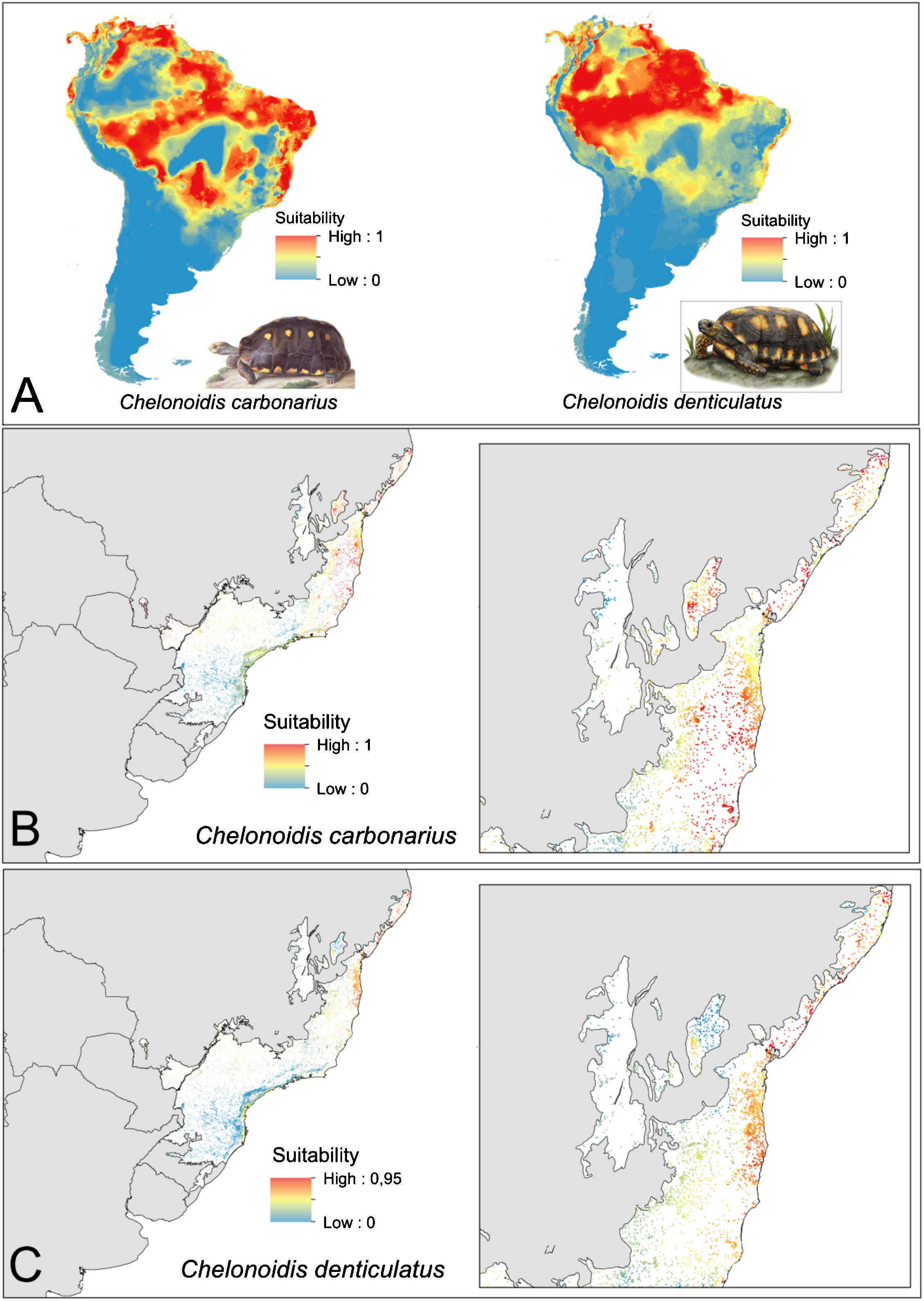

ResultsEcological niche modelsThe ENMs show different distribution patterns for the two tortoise species. The models for C. denticulatus identified suitable areas mainly in the Amazon biome and in a few areas in the Brazilian northeast within the AF domain (Fig. 2A). In turn, the models predicted a broader distribution of C. carbonarius with highly suitable areas in the eastern Amazon, the coastal zone of Caatinga, some areas of central Cerrado and in northern areas of the AF (Fig. 2A). The analysis of the suitability of AF forest fragments for tortoise reintroductions showed that fragments have high suitability for C. denticulatus only in the northern AF, while fragments have high suitability for C. carbonarius in the northern and central fragments (Fig. 2B and C).

Tortoise species distribution patterns. (A) Distribution predictions across the South American continent. (B) Suitability of Atlantic Forest remnants for C. carbonarius. (C) Suitability of Atlantic Forest remnants for C. denticulatus. The suitability values vary between 0 (low suitability) and 1 (high suitability).

We found 95 plant taxa dispersed by C. denticulatus and C. carbonarius in three Brazilian biomes, namely the Atlantic Forest, the Amazon forest and the Cerrado (Table S1). The most frequently dispersed taxa recorded were small-seeded species (Ficus spp., Genipa americana, Brosimum lactescens, Jacaratia spinosa, Jacaratia digitate) but also large seeded species (Spondias dulcis, Mauritia flexuosa, and Syagrus oleracea). Indeed, 28% of these species have large seeds (i.e. >12mm wide) and could potentially face recruitment disruption due to the loss of large-bodied frugivores (Cardoso da Silva and Tabarelli, 2000), since their main dispersers are mammals, such as primates and/or large birds, which are likely absent in small fragments.

We found 95 plant taxa dispersed by C. denticulatus and C. carbonarius in three Brazilian biomes, namely the Atlantic forest, the Amazon forest and the Cerrado (Table S1). The most frequently dispersed taxa recorded were small-seeded species (Ficus spp., Genipa americana, Brosimum lactescens, Jacaratia spinosa, Jacaratia digitate) but also large seeded species (Spondias dulcis, Mauritia flexuosa, and Syagrus oleracea). Indeed, 28% of these species have large seeds (i.e. >12mm wide) and potentially could face recruitment disruption due to the loss of large-bodied frugivores (Cardoso da Silva and Tabarelli, 2000), since their main dispersers are mammals, such as primates and/or large birds, which are likely absent in small fragments.

Both tortoise species can consume and disperse seeds up to 25mm wide, though the mean size of ingested seeds is 8.53(±6.62)mm. Based on plant species that occur in the AF biome and phylogenetic closeness with species known to be dispersed by tortoises in Amazon and Cerrado, we estimated that tortoises could potentially disperse 338 taxa in the AF (Table S1). Considering the recorded plant taxa and those potentially dispersed by both tortoises, 84 of the species potentially dispersed by tortoises in the AF are currently threatened with extinction due to habitat loss (Table S1).

Both tortoise species can consume and disperse seeds up to 25mm wide, though the mean size of ingested seeds is 8.53(±6.62)mm. Based on plant species that occur in the AF biome and phylogenetic closeness with species known to be dispersed by tortoises in Amazon and Cerrado, we estimated that tortoises could potentially disperse 338 taxa in the AF (Table S1). Considering the recorded plant taxa and those potentially dispersed by both tortoises, 84 of the species potentially dispersed by tortoises in the AF are currently threatened with extinction due to habitat loss (Table S1).

Selection of areas for tortoise rewildingThe most feasible areas for tortoise reintroduction are located in the north and central parts of the AF. However, feasible areas for C. carbonarius expand more to the south than potential areas for C. denticulatus which concentrated just in the north part (Fig. 3A). The geographical analysis of potential areas of C. carbonarius indicated that fragments in southern AF, such as in the Serra do Mar mountain range, can offer good food availability and a good trade-off for endangered species. However, these fragments have low environmental suitability for the species occurrence (Fig. 3A). Almost the same pattern remains for C. denticulatus, nevertheless the food availability for this species is mostly concentrated in the northern part limiting the expansion to southern areas (Fig. 3B).

The rewilding of C. carbonarius in the AF would have dispersal benefits for at least 113 plant taxa, of which 44 are endangered, while rewilding of C. denticulatus would benefit the dispersal of 57 taxa, of which 21 are endangered. Thus, we indicate 15 northern AF remnants as the best areas for tortoise rewilding (Fig. 4 – red/orange circle). In these fragments, we have the highest potential benefits of seed dispersal of many plants taxa including the co-benefits of seed dispersal of endangered taxa, mainly by C. denticulatus (Fig. 4). Our selection of these fragments for tortoise rewilding is reinforced by noting that they are among the most highly defaunated ones, according to the AF defaunation level map proposed by Jorge et al. (2013) (Fig. 4).

Comparison between Brazilian Atlantic Forests defaunated areas pattern, derivate of surrogate mammals’ richness proposed by Jorge et al. (2013) and the feasibility index of Chelonoidis species into the Atlantic Forest remnants.

One of the major challenges for conservation biologists is to revert the negative ecological processes caused by defaunation (Seddon et al., 2014; Galetti et al., 2017). Even if the poaching stops in tropical forests, many areas are already too small to maintain large-bodied vertebrates (Jorge et al., 2013; Benchimol and Peres, 2015). The introduction of ecological analogs, with giant tortoises among the foremost candidates for replacement, has been advocated as a method to revert the consequences of defaunation in oceanic islands (Hansen et al., 2010; Griffiths et al., 2010). Here, we argue that C. denticulatus and C. carbonarius tortoises can also be used as ecological analogs of large seeded dispersers in highly defaunated forests that are not able to sustain viable population of large vertebrates.

The rewilding of both tortoises in the northern and central AF remnants would represent dispersal and conservation co-benefit for more than 100 tree species, primarily in the case of C. carbonarius. Some of those are large-seeded species that are eaten by few large-bodied vertebrates, such as tapir and large primates (Jerozolimski et al., 2009; Bello et al., 2017). These species include large canopy timber tree (e.g. Sapotaceae and Chrysobalanaceae) and dominant palms of the AF (e.g. Euterpe edulis and Attalea spp.). Many of these large-seeded species are known to sustain a large fraction of the standing above ground biomass (Ter Steege, 2013) and recent studies have suggested that the extinction of large frugivores may erode the carbon storing capacity in the AF (Bello et al., 2015). Since most of the AF patches are not able to sustain tapirs and Ateline monkeys (Brachyteles spp.) (Jorge et al., 2013), we could expect that many large seeded plant species will be facing a demographic bottleneck (Galetti et al., 2006; Bueno et al., 2013; Bufalo et al., 2016). Thus, tortoises can play an important role in vegetation dynamics, especially in fragmented and defaunated AF localities.

C. carbonarius and C. denticulatus are opportunistic feeders with between 28% and 38% of their diet represented by fruits (Guzmán and Stevenson, 2008; Jerozolimski et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011). Jerozolimski et al. (2009) estimated that a population of C. denticulatus is able to disperse from 479,462 to 594,533seeds/km2/year and high percentages of these seeds are considered viable (91–100%) because tortoises do not chew food as many mammals do, but tear off the fruit into pieces small enough to fit in their mouth and swallow, leaving a high percentage of intact seeds when defecating (Strong and Fragoso, 2006). In addition, both tortoises species can persist in a small home range (c. 0.5ha) (Jerozolimski, 2003; Moskovits and Kiester, 1987) and can reach high densities, being registered from 5.1individuals/km2 (Peres et al., 2003) to 31.4individuals/km2 (Jerozolimski, 2003) for C. denticulatus in two different areas in the Amazon. Therefore, the high proportion of viable seeds, combined with high population densities and seed loads in some fecal samples, suggest that tortoises are high-potential seed dispersers.

In addition to the contribution to the maintenance of the ecosystems functions, rewilding with tortoises can reinforce the conservation efforts for both species and for the endangered plant taxa that they disperse. Both species are currently threatened with extinction. C. denticulatus is classified as vulnerable according to the IUCN Red List (Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, 1996) and C. carbonarius, even though not yet officially evaluated by the IUCN, is endangered and even extinct in several parts of its former geographic range (Walker, 1989). The human impact have contributed to the worldwide extinction of many tortoise species since the Quaternary (Rhodin et al., 2015). In the Brazilian Amazon, for instance, tortoises still figure among the species with the highest rates of consumption by human populations (Van Vliet et al., 2014; Peres, 2000). However, at the landscape scale, the rural consumption of tortoises in the Amazon could be considered a low-impact activity due to source-sink dynamics, while the urban trade can lead to an unsustainable harvest (Morcatty and Valsecchi, 2015a). On the other hand, there is no current information on tortoise exploitation in the AF remnants, such as recorded for mammals, which are the most targeted group in this biome, especially for sport motivation (El Bizri et al., 2015). Even though turtles would be hunting targets in some areas, legal captive-bred individuals are already a plausible alternative to the wild-caught ones. Therefore, the main threat to tortoises is habitat loss due to the high rate of habitat conversion into pastureland and agriculture, and urbanization (Wang et al., 2011).

Here, we propose that tortoise rewilding is a potential strategy to restore dysfunctional ecological processes in defaunated patches of the northern Atlantic Forest. However, many questions remain about the practicalities of such conservation actions. For example, what could be the source of the reintroduced individuals? There are many zoos and conservation breeders that could provide individuals for tortoise rewilding in the Atlantic Forest, particularly those coming from seizures of illegal trade. Both species breed easily, can be monitored with low cost and have few predators in small fragments (Emmons, 1989). However, the risk of tortoise capture by humans should be considered in rewilding projects, especially the capture aiming at supplying the pet market in Brazil. Thus, for a tortoise rewilding project to succeed, environmental education programs against the collection and hunting of reintroduced animals must be implemented in the selected Atlantic Forest fragments.

In addition, there are several preparations that need to take place before releasing specimens in the wild during rewilding projects. Reintroduction can be a useful tool to re-establish viable populations of a species within its indigenous range as long as a detailed assessment of ecological, social and economic risks is performed. Following the recommendations by the IUCN Species Survival Commission for rewilding, it would be important to make sure that the patch chosen for rewilding with tortoises was within the indigenous range of the target species, and to determine if there would already be a resident population in the receiving forest fragment. In addition, it is desirable to assess the genetic variation in the donor population(s) to guarantee that the founders of the rewilded populations have an adequate genetic pool that maximizes the likelihood of the permanence of the introduced population.

One of the main threats posed by translocations is the risk of introducing new pathogens or spreading diseases. Thus, it is necessary with a strong effort to reduce parasite loads in the potentially reintroduced individuals. Intrinsic characteristics of each species’ natural populations must also be considered, such as the sex and age ratios, and the potential for detrimental ecological relationships between the reintroduced species and the already-present natural species, such as predation and competition.

To perform responsible and effective rewilding projects it is important to plan long-term programs that monitor the reproduction and mortality rates, health and the population genetics. Periodical monitoring of the reintroduced tortoise populations as well as key target plant species would enable us to evaluate the effectiveness of the translocation for the environment and detect possible negative effects.

Here we appointed the use of two tortoise species as rewilding species for small and defaunated fragments of northern AF. We based our target in the high suitability and food availability properties of these remnants and in the capacity of these species in dispersing many plant taxa, including high seeded and threatened taxa. We encourage further studies that use the same ENMs methods applied by us, and the use of tortoise as ecological substitute to maintain ecosystem services in highly defaunated sites.

We thank Maria Luisa Jorge for providing the defaunation map and Renato Lima for made available the TREECO database. We thank Matheus S. Lima-Ribeiro, Jean Paul Metzger and an anonymous reviewer for the manuscript review. TSS thanks to the CNPq for the postdoc fellowship (process number 150319/2017-7) and the Unimes for the logistic support. CB thanks FAPESP for the obtained grant (2013/22492-2). MG receives a fellowship from CNPq (300970/2015-3) and FAPESP (2014/01986-0).